Via Panorâmica 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faraone Ancient Greek Love Magic.Pdf

Ancient Greek Love Magic Ancient Greek Love Magic Christopher A. Faraone Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Copyright © 1999 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Second printing, 2001 First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2001 library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Faraone, Christopher A. Ancient Greek love magic / Christopher A. Faraone. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 0-674-03320-5 (cloth) ISBN 0-674-00696-8 (pbk.) 1. Magic, Greek. 2. Love—Miscellanea—History. I. Title. BF1591.F37 1999 133.4Ј42Ј0938—dc21 99-10676 For Susan sê gfir Ãn seautá tfi f©rmaka Æxeiv (Plutarch Moralia 141c) Contents Preface ix 1 Introduction 1 1.1 The Ubiquity of Love Magic 5 1.2 Definitions and a New Taxonomy 15 1.3 The Advantages of a Synchronic and Comparative Approach 30 2 Spells for Inducing Uncontrollable Passion (Ero%s) 41 2.1 If ErÃs Is a Disease, Then Erotic Magic Is a Curse 43 2.2 Jason’s Iunx and the Greek Tradition of Ago%ge% Spells 55 2.3 Apples for Atalanta and Pomegranates for Persephone 69 2.4 The Transitory Violence of Greek Weddings and Erotic Magic 78 3 Spells for Inducing Affection (Philia) 96 3.1 Aphrodite’s Kestos Himas and Other Amuletic Love Charms 97 3.2 Deianeira’s Mistake: The Confusion of Love Potions and Poisons 110 3.3 Narcotics and Knotted Cords: The Subversive Cast of Philia Magic 119 4 Some Final Thoughts on History, Gender, and Desire 132 4.1 From Aphrodite to the Restless -

Evelyn De Morgan Y La Hermandad Prerrafaelita

Trabajo Fin de Grado Lux in Tenebris: Evelyn De Morgan y la Hermandad Prerrafaelita Lux in Tenebris: Evelyn De Morgan and the Pre- Raphaelite Brotherhood. Autor/es Irene Zapatero Gasco Director/es Concepción Lomba Serrano Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Curso 2018/2019 LUX IN TENEBRIS: EVELYN DE MORGAN Y LA HERMANDAD PRERRAFAELITA IRENE ZAPATERO GASCO DIRECTORA: CONCEPCIÓN LOMBA SERRANO HISTORIA DEL ARTE, 2019 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN - JUSTIFICACIÓN DEL TRABAJO…………………………………....1 - OBJETIVOS…………………………………………………………....2 - METODOLOGÍA……………………………………………………....2 - ESTADO DE LA CUESTIÓN………………………………………....3 - AGRADECIMIENTOS………………………………………………...5 LA ÉPOCA VICTORIANA - CONTEXTO HISTORICO…………………………………………….6 - EL PAPEL QUE DESEMPEÑABA LA MUJER EN LA SOCIEDAD…………………………………………………………….7 LA HERMANDAD PRERRAFAELITA…………………………………...10 EVELYN DE MORGAN - TRAYECTORIA E IDEOLOGÍA ARTÍSTICA……………………...13 - EL IDEAL ICÓNICO RECREADO…………………..……………....15 - LA REPRESENTACIÓN DE LA MUJER EN SU PRODUCCIÓN ARTÍSTICA...........................................................................................16 I. EL MUNDO ESPIRITUAL…………………………………...17 II. HEROÍNAS SAGRADAS…………………………………….21 III. ANTIBELICISTAS…………………………………………....24 CONCLUSIONES…………...……………………………………………….26 BIBLIOGRAFÍA Y WEBGRAFÍA…………………………………………28 ANEXOS….……………………………………………………………..........32 - REPERTORIOGRÁFICO…………………………………………….46 INTRODUCCIÓN JUSTIFIACIÓN DEL TRABAJO Centrado en la obra de la pintora Evelyn De Morgan (1855, Londres) nuestro trabajo pretende revisar su producción artística contextualizándola -

Reading William Morris, Peter Kropotkin, Ursula K. Le Guin, and PM in the Light of Digital Socialism

tripleC 18(1): 146-186, 2020 http://www.triple-c.at The Utopian Internet, Computing, Communication, and Concrete Utopias: Reading William Morris, Peter Kropotkin, Ursula K. Le Guin, and P.M. in the Light of Digital Socialism Christian Fuchs University of Westminster, London, [email protected], http://fuchs.uti.at Abstract: This paper asks: What can we learn from literary communist utopias for the creation and organisation of communicative and digital socialist society and a utopian Internet? To pro- vide an answer to this question, the article discusses aspects of technology and communica- tion in utopian-communist writings and reads these literary works in the light of questions con- cerning digital technologies and 21st-century communication. The selected authors have writ- ten some of the most influential literary communist utopias. The utopias presented by these authors are the focus of the reading presented in this paper: William Morris’s (1890/1993) News from Nowhere, Peter Kropotkin’s (1892/1995) The Conquest of Bread, Ursula K. Le Guin’s (1974/2002) The Dispossessed, and P.M.’s (1983/2011; 2009; 2012) bolo’bolo and Kartoffeln und Computer (Potatoes and Computers). These works are the focus of the reading presented in this paper and are read in respect to three themes: general communism, technol- ogy and production, communication and culture. The paper recommends features of concrete utopian-communist stories that can inspire contemporary political imagination and socialist consciousness. The themes explored include the role of post-scarcity, decentralised comput- erised planning, wealth and luxury for all, beauty, creativity, education, democracy, the public sphere, everyday life, transportation, dirt, robots, automation, and communist means of com- munication (such as the “ansible”) in digital communism. -

Pictorial Index to Mythological Characters in Tennyson's

MOORE Pictorial Index to Mythological Characters In Tennyson's Princess / -V Library Science B, L. S. 1904 1 , UNJVI-KSITT OF *IX. XlBRARTf wmmm * ^ ^ * ^ # + * m v^l^ i^ISps PIP * :# UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY Mmlk PI BOOK CLASS VOLUME P^lJSP?\Mm>Mm \m$ * i m H ill* ilflNl 4 # mmm. i The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return to the library from 4 which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. ii^jPo UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URB ANA-CHAMPAIGN ^ifP ^l^l!^^ ^^^^^ BUILDING USE ONLY T w- W W ~ W r ~0%^{ • ^ i i/^^x' i/l^ff^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ tip* * -^^PIMP^ " " ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ 1 L161 — O-1096 if:m IK * " PICTORIAL INDEX - TO MYTHOLOGICAL CHARACTERS IN TENNYSON 1 S " PRINCESS • ERMA JANE MOORE THESIS PRESENTED FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF LIBRARY SCIENCE IN THE ILLINOIS STATE LIBRARY SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS JUNE 1904 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 4- 1 !H> THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY \D IXnoouQ^. ^O^OJL XlXjoxyfXSL ENTITLED ^-kjlXxtuuoS* LxudxoL to vn t^XOJlJD^ciXnjD LT\ ^X^VL'T^OOXLO. I?/ is APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Sjxj^?xJL.i-o^ ai CiJLoxuiJU 2>.j ..£4., HEAD OF DEPARTMEXT OF Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/pictorialindextoOOmoor . -1- INTRODUCTORY NOTE In the following pictorial index to the characters of classic al mythology in Tennyson's "Princess", books and periodicals relat- ing to art, mythology and antiquities have been consulted; and from a great amount of material these references have been chosen. -

Michael Berkeley and David Malouf's Rewriting of Jane Eyre: an Operatic and Literary Palimpsest*

CHAPTER 6 Michael Berkeley and David Malouf’s Rewriting of Jane Eyre: An Operatic and Literary Palimpsest* Jean-Philippe Heberlé English composer Michael Berkeley (born 1948) is the son of Lennox Berkeley (1903–1989), himself a composer of instrumental music and operas including, for instance, A Dinner Engagement (1955) and Ruth (1955–56). To this day, Michael Berkeley has written three operas and is currently working on a new operatic project based on Ian McEwan’s novel Atonement (2001). For his first two operas (Baa Baa Black Sheep, 1993, and Jane Eyre, 2000), he collaborated with acclaimed Australian novelist David Malouf (born 1934). This chap- ter addresses Berkeley’s second opera, Jane Eyre, a chamber opera1 premiered at the Cheltenham Music Festival on June 30, 2000. The opera by David Malouf and Michael Berkeley appears to be an oper- atic and literary palimpsest in which Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre is compressed and distorted into a concentrated operatic drama of little more than 70 minutes.2 Five characters form the cast, and the storyline focuses exclusively on the events at Thornfield. In this intertextual3 and intermedial4 analysis of Berkeley and Malouf’s operatic adapta- tion of Jane Eyre, a study of the text and the music reveals whether the librettist and the composer focalized or not on particular elements and episodes of the original novel. The artists at times amended, dis- torted, or retained elements of the novel, allowing their new work to interpret Charlotte Brontë’s novel’s psychologically developed char- acters and its gothic atmosphere. Finally, the opera and its libretto function metadramatically. -

Michael Berkeley Selected Reviews

Michael Berkeley Selected Reviews Winter Fragments (Chamber Music Recording) Resonus Classics RES10223 (September 2018) “Stylistically ranging from the plainchant-inspired Clarinet Quintet (1983) to the sensuous and Satie-like Seven (2007), to the jostling intensity of Catch Me If You Can (1994), it shows Berkeley at his exploratory and individualistic best, free to follow his instinct, tonal or expressionistic” – Fiona Maddocks, The Guardian “Even when working with large-scale forces such as opera and music theatre, Michael Berkeley's style and expression remain attuned to the more intimate nuances of chamber music. Perhaps this is because the chamber context provides such an effective vehicle for one of his music's most distinctive features - the often dichotomous interplay between the individual and the group... the Berkeley Ensemble, directed by Dominic Grier, are excellent throughout - entirely at one with the music of their namesake composer” – Pwyll ap Sion, Gramophone “There’s contrast aplenty – Catch Me If You Can (1994) a feisty, frenetic triptych, the gentle, self-echoing, harp-centred Seven (2007) pregnant with a pensiveness that collides late Mahler with Satie at his most subdued. The Clarinet Quintet (1983) is spun from sinewy, twisting strands contrasting the playful impetuosity and dark-hued luminosity of John Slack’s clarinet to end in a moment of sublimely subdued beauty. 2010’s Rilke-setting Sonnet for Orpheus and the seven-part song-cycle Winter Fragments (1996) – both benefiting from Fleur Barron’s ardent mezzo – -

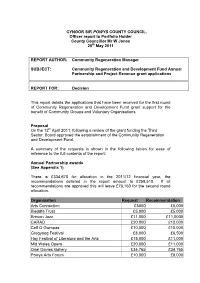

Community Regeneration and Development Fund Annual Partnership and Project Revenue Grant Applications

CYNGOR SIR POWYS COUNTY COUNCIL. Officer report to Portfolio Holder County Councillor Mr W Jones 25 th May 2011 REPORT AUTHOR: Community Regeneration Manager SUBJECT: Community Regeneration and Development Fund Annual Partnership and Project Revenue grant applications REPORT FOR: Decision This report details the applications that have been received for the first round of Community Regeneration and Development Fund grant support for the benefit of Community Groups and Voluntary Organisations. Proposal On the 12 th April 2011, following a review of the grant funding the Third Sector, Board approved the establishment of the Community Regeneration and Development Fund. A summary of the requests is shown in the following tables for ease of reference to the full contents of the report: Annual Partnership awards (See Appendix 1) There is £334,670 for allocation in the 2011/12 financial year, the recommendations detailed in the report amount to £258,510. If all recommendations are approved this will leave £76,160 for the second round allocation. Organisation Request Recommendation Arts Connection £5000 £5,000 Bleddfa Trust £5,000 £5,000 Brecon Jazz £11,000 £11,0000 CARAD £20,000 £12,000 Celf O Gwmpas £10,000 £10,000 Gregynog Festival £8,000 £6,500 Hay Festival of Literature and the Arts £15,000 £11,000 Mid Wales Opera £20,000 £11,000 Oriel Davies Gallery £34,765 £34,765 Powys Arts Forum £10,000 £8,000 Powys Association Of Voluntary Organisations £30,000 £30,000 Powys Leisure Services £24,000 £12,000 Play Montgomeryshire £15,000 £15,000 Powys Federation of Women’s Institutes £2,400 £2,400 Presteigne Festival of the Arts £10,000 £9,000 Presteigne Shire Hall Museum Trust Ltd £7,500 £7,500 Wyeside Arts Centre £47,025 £47,025 Llandrindod Wells Victorian Festival £11,000 £11,000 Wales Pre-school Playgroup Assoc. -

Annual Report October 2011–September 2013

HOUSE OF LORDS APPOINTMENTS COMMISSION ANNUAL REPORT October 2011 to September 2013 House of Lords Appointments Commission Page 3 Contents Section 1: The Appointments Commission 5 Section 2: Appointments of non-party-political peers 8 Section 3: Vetting party-political nominees 11 Annex A: Biographies of the Commission 14 Annex B: Individuals vetted by the Commission 16 and appointed to the House of Lords [Group photo] Page 4 Section 1 The Appointments Commission 1. In May 2000 the Prime Minister established the House of Lords Appointments Commission as an independent, advisory, non-departmental public body. Commission Membership 2. The Commission has seven members, including the Chairman. Three members represent the main political parties and ensure that the Commission has expert knowledge of the House of Lords. The other members, including the Chairman, are independent of government and political parties. The independent members were appointed in October 2008 by open competition, in accordance with the code of the Commissioner for Public Appointments. The party-political members are all members of the House of Lords and were nominated by the respective party leader in November 2010 for three year terms. 3. The terms of all members therefore come to an end in the autumn of 2013. 4. Biographies of the Commission members can be seen at Annex A. 5. The Commission is supported by a small secretariat at 1 Horse Guards Road, London SW1A 2HQ. Role of the House of Lords Appointments Commission 6. The role of the Commission is to: make recommendations for the appointment of non-party-political members of the House of Lords; and vet for propriety recommendations to the House of Lords, including those put forward by the political parties and Prime Minister. -

Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects

Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects Giorgio Vasari Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects Table of Contents Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects.......................................................................1 Giorgio Vasari..........................................................................................................................................2 LIFE OF FILIPPO LIPPI, CALLED FILIPPINO...................................................................................9 BERNARDINO PINTURICCHIO........................................................................................................13 LIFE OF BERNARDINO PINTURICCHIO.........................................................................................14 FRANCESCO FRANCIA.....................................................................................................................17 LIFE OF FRANCESCO FRANCIA......................................................................................................18 PIETRO PERUGINO............................................................................................................................22 LIFE OF PIETRO PERUGINO.............................................................................................................23 VITTORE SCARPACCIA (CARPACCIO), AND OTHER VENETIAN AND LOMBARD PAINTERS...........................................................................................................................................31 -

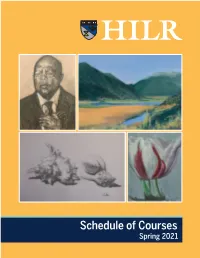

Schedule of Courses Spring 2021 Spring 2021 Courses at a Glance

Schedule of Courses Spring 2021 Spring 2021 Courses at a Glance Spring 2021 Courses at a Glance MONDAY, 10 AM–12 NOON 104 Braiding Sweetgrass: Thinking about Nature and Humankind Fred Chanania 300 China and the US: Relations Since 1776 Easley Hamner 105 Eudora Welty’s Stories and Reflections on Writing Joanne Carlisle 301 Ninth Street Women: Heroines of Abstract Expressionism and Beyond 106 Population Matters Laura Becker Mary Jo Bane *302 The First Artists: Cave Art 203 New England Trees and Forests: Then and Now Ron Ebert Fred Chanania 303 The Harlem Renaissance 204 Old Problems/New Voices: 2020 African-American Novels Martha Vicinus Linda Sultan 100 The Makioka Sisters: A Japanese Tale of Love and Cultural Upheaval 205 Richard III: Villain or Victim? Barbara Burr and Winthrop Burr Jennifer Huntington 101 Writing Epidemics 206 Truman’s Decision Burns Woodward Joan McGowan 200 Listening for America: Gershwin to Sondheim TUESDAY, 1 PM–3 PM Steven Roth 314 A Perspective on the Development of Homo Sapiens MONDAY, 1 PM–3 PM Jeffrey Berman 304 Balzac’s Lost Illusions 315 Conversations with Joan Didion Andrea Gargiulo Randy Cronk 305 Existential Questions 316 Deliberative Democracy: Can We Have Democracy without Amanda Gruber Elections? Helena Halperin *306 Great Decisions 2021 Carol Kunik and Dottie Stephenson 317 How Hemingway Became Hemingway Susan Ebert *307 Reading or Rereading The Odyssey in a New Translation Marcia Folsom *318 Literary Portraits of White Supremacy: Paton, Wright, and Gordimer 308 The Long Evolution of Spin: Where Have -

Drama and Lyric Drama and Lyric

Old Western Culture A Christian Approach to the Great Books T H E G R E E K S DRAMA Guide to the Art The Blind Oedipus Commending His Children to the Gods B�nigne Gagneraux, 1784, oil on canvas AND LYRIC Drama and Lyric is the second installment in The Greeks, year one of the Old Western Culture series. Join Wesley Callihan as he uncovers the origins of The Tragedies, Comedies, and Minor Poems Greek drama and guides studenta through some of the earliest comedies and tragedies known to the Western world. Learn how the political backdrop of the Greco-Persian wars informs our understanding of Athenian drama, as well as the comedies of Aristophanes—one of the earliest known examples of cultural and political satire. Drama and Lyric also covers some of the lesser known poets of Ancient Greece such as Sappho and Pindar, whose works are somewhat 2 obscure, yet nevertheless affected the writing of men such as C. S. Lewis. Wesley Callihan ABOUT ROMAN ROADS MEDIA Introduction and Overview Roman Roads combines its technical expertise with How to Use This Course the experience of established authorities in the field of classical education to create quality video resources Old Western Culture: A Christian Approach to the Great Books is a four-year course tailored to the homeschooler. Just as the first century of study designed for grades 9–12. Each year of Old Western Culture is a roads of the Roman Empire were the physical means double-credit literature and social studies course. The four units that make by which the early church spread the gospel far and up each year may also be used individually as one-quarter electives. -

Dragon Magazine #163

SPECIAL ATTRACTIONS Issue #163 9 The endless challenge of magic. Vol. XV, No. 6 November 1990 Back To School Magic School! Gregory W. Detwiler 10 If you want to be a specialist mage, youd better know each schools Publisher pros and cons. James M. Ward Oops! Sorry! Donald Hoverson Editor 15 So you miscast a fireball spell. What could possibly happen? Roger E. Moore Hedge Wizards Gregg Sharp 18 Some mages are perfectly happy to see a dungeon. Fiction editor never Barbara G. Young Magic Gone Haywire Rich Stump 27 Lots of things can go wrong with a magical item. Such as . Assistant editor Dale A. Donovan A Hoard For the Horde David Zeb Cook Insert A gatefold special: A hoard (horde?) of four new monsters for the Art director FORGOTTEN REALMS setting. Larry W. Smith Production staff OTHER FEATURES Gaye OKeefe Angelika Lokotz Tracey Zamagne The Role of Books John C. Bunnell 32 Murders most foul in universes most bizarre. Subscriptions Janet L. Winters The Voyage of the Princess Ark Bruce A. Heard 41 Betrayal and escapeinto the claws of darkness. U.S. advertising The Role of Computers Hartley, Patricia, and Kirk Lesser Roseann Schnering 47 When a dungeon thaws out, it goes bad right away. U.K. correspondent Storm Winter fiction by M. C. Sumner and U.K. advertising 58 Her father was kidnapped. Then a kidnapper came to ask for her help. Sue Lilley The MARVEL®-Phile David E. Martin, Chris Mortika, Scott Davis, 71 and William Tracy Just because a villain is dead doesnt mean you cant bring him to life.