The Arts and the Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michael Berkeley and David Malouf's Rewriting of Jane Eyre: an Operatic and Literary Palimpsest*

CHAPTER 6 Michael Berkeley and David Malouf’s Rewriting of Jane Eyre: An Operatic and Literary Palimpsest* Jean-Philippe Heberlé English composer Michael Berkeley (born 1948) is the son of Lennox Berkeley (1903–1989), himself a composer of instrumental music and operas including, for instance, A Dinner Engagement (1955) and Ruth (1955–56). To this day, Michael Berkeley has written three operas and is currently working on a new operatic project based on Ian McEwan’s novel Atonement (2001). For his first two operas (Baa Baa Black Sheep, 1993, and Jane Eyre, 2000), he collaborated with acclaimed Australian novelist David Malouf (born 1934). This chap- ter addresses Berkeley’s second opera, Jane Eyre, a chamber opera1 premiered at the Cheltenham Music Festival on June 30, 2000. The opera by David Malouf and Michael Berkeley appears to be an oper- atic and literary palimpsest in which Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre is compressed and distorted into a concentrated operatic drama of little more than 70 minutes.2 Five characters form the cast, and the storyline focuses exclusively on the events at Thornfield. In this intertextual3 and intermedial4 analysis of Berkeley and Malouf’s operatic adapta- tion of Jane Eyre, a study of the text and the music reveals whether the librettist and the composer focalized or not on particular elements and episodes of the original novel. The artists at times amended, dis- torted, or retained elements of the novel, allowing their new work to interpret Charlotte Brontë’s novel’s psychologically developed char- acters and its gothic atmosphere. Finally, the opera and its libretto function metadramatically. -

Michael Berkeley Selected Reviews

Michael Berkeley Selected Reviews Winter Fragments (Chamber Music Recording) Resonus Classics RES10223 (September 2018) “Stylistically ranging from the plainchant-inspired Clarinet Quintet (1983) to the sensuous and Satie-like Seven (2007), to the jostling intensity of Catch Me If You Can (1994), it shows Berkeley at his exploratory and individualistic best, free to follow his instinct, tonal or expressionistic” – Fiona Maddocks, The Guardian “Even when working with large-scale forces such as opera and music theatre, Michael Berkeley's style and expression remain attuned to the more intimate nuances of chamber music. Perhaps this is because the chamber context provides such an effective vehicle for one of his music's most distinctive features - the often dichotomous interplay between the individual and the group... the Berkeley Ensemble, directed by Dominic Grier, are excellent throughout - entirely at one with the music of their namesake composer” – Pwyll ap Sion, Gramophone “There’s contrast aplenty – Catch Me If You Can (1994) a feisty, frenetic triptych, the gentle, self-echoing, harp-centred Seven (2007) pregnant with a pensiveness that collides late Mahler with Satie at his most subdued. The Clarinet Quintet (1983) is spun from sinewy, twisting strands contrasting the playful impetuosity and dark-hued luminosity of John Slack’s clarinet to end in a moment of sublimely subdued beauty. 2010’s Rilke-setting Sonnet for Orpheus and the seven-part song-cycle Winter Fragments (1996) – both benefiting from Fleur Barron’s ardent mezzo – -

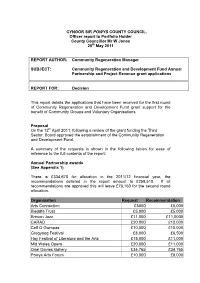

Community Regeneration and Development Fund Annual Partnership and Project Revenue Grant Applications

CYNGOR SIR POWYS COUNTY COUNCIL. Officer report to Portfolio Holder County Councillor Mr W Jones 25 th May 2011 REPORT AUTHOR: Community Regeneration Manager SUBJECT: Community Regeneration and Development Fund Annual Partnership and Project Revenue grant applications REPORT FOR: Decision This report details the applications that have been received for the first round of Community Regeneration and Development Fund grant support for the benefit of Community Groups and Voluntary Organisations. Proposal On the 12 th April 2011, following a review of the grant funding the Third Sector, Board approved the establishment of the Community Regeneration and Development Fund. A summary of the requests is shown in the following tables for ease of reference to the full contents of the report: Annual Partnership awards (See Appendix 1) There is £334,670 for allocation in the 2011/12 financial year, the recommendations detailed in the report amount to £258,510. If all recommendations are approved this will leave £76,160 for the second round allocation. Organisation Request Recommendation Arts Connection £5000 £5,000 Bleddfa Trust £5,000 £5,000 Brecon Jazz £11,000 £11,0000 CARAD £20,000 £12,000 Celf O Gwmpas £10,000 £10,000 Gregynog Festival £8,000 £6,500 Hay Festival of Literature and the Arts £15,000 £11,000 Mid Wales Opera £20,000 £11,000 Oriel Davies Gallery £34,765 £34,765 Powys Arts Forum £10,000 £8,000 Powys Association Of Voluntary Organisations £30,000 £30,000 Powys Leisure Services £24,000 £12,000 Play Montgomeryshire £15,000 £15,000 Powys Federation of Women’s Institutes £2,400 £2,400 Presteigne Festival of the Arts £10,000 £9,000 Presteigne Shire Hall Museum Trust Ltd £7,500 £7,500 Wyeside Arts Centre £47,025 £47,025 Llandrindod Wells Victorian Festival £11,000 £11,000 Wales Pre-school Playgroup Assoc. -

Annual Report October 2011–September 2013

HOUSE OF LORDS APPOINTMENTS COMMISSION ANNUAL REPORT October 2011 to September 2013 House of Lords Appointments Commission Page 3 Contents Section 1: The Appointments Commission 5 Section 2: Appointments of non-party-political peers 8 Section 3: Vetting party-political nominees 11 Annex A: Biographies of the Commission 14 Annex B: Individuals vetted by the Commission 16 and appointed to the House of Lords [Group photo] Page 4 Section 1 The Appointments Commission 1. In May 2000 the Prime Minister established the House of Lords Appointments Commission as an independent, advisory, non-departmental public body. Commission Membership 2. The Commission has seven members, including the Chairman. Three members represent the main political parties and ensure that the Commission has expert knowledge of the House of Lords. The other members, including the Chairman, are independent of government and political parties. The independent members were appointed in October 2008 by open competition, in accordance with the code of the Commissioner for Public Appointments. The party-political members are all members of the House of Lords and were nominated by the respective party leader in November 2010 for three year terms. 3. The terms of all members therefore come to an end in the autumn of 2013. 4. Biographies of the Commission members can be seen at Annex A. 5. The Commission is supported by a small secretariat at 1 Horse Guards Road, London SW1A 2HQ. Role of the House of Lords Appointments Commission 6. The role of the Commission is to: make recommendations for the appointment of non-party-political members of the House of Lords; and vet for propriety recommendations to the House of Lords, including those put forward by the political parties and Prime Minister. -

Visual Interpretations of the Score in Painting and Digital Media

Journal of the International Colour Association (2013): 11, 37-50 Laycock Visual interpretations of the score in painting and digital media Kevin Laycock School of Design, University of Leeds, UK Email: [email protected] Historically much of the activity in the area of visual music has been focused on the creation of visual compositions stimulated by musical performance. I suggest that the intuitive act of painting to live and or recorded music is flawed in its interpretation of the musical intentions of a composers score. For the purpose of this investigation the studio practice concentrates on the shared systems and language of composition, what Zilcer identifies as the ‘application of formal compositional elements of music to painting’1. In part, the project will draws on the expertise of British composer Michael Berkeley and conductor Peter Manning2. The premise for the research is to identify the presence of process and system in each of the practitioner’s work. Also through collaboration with a composer and conductor the project offers a further opportunity to consider the effects of music found in contemporary painting practice. The initial findings of the research are used to establish an intellectual framework where neither the audible or visual elements of the disciplines take precedence over each other. Received 20 March 2013; revised 25 June 2013; accepted 1 July 2013 Published online: 30 July 2013 There are many examples of painters, who have sloshed paint around the canvas in the pursuit of what Walter Pater defined as the “condition of music3”. This type of expressionistic painting is fundamentally intuitive and is often a by-product of listening and painting. -

Album Booklet

Clarion Call Music for Septet and Octet John Casken • Howard Ferguson • Michael Berkeley • Charles Wood Berkeley Ensemble RES10127 Clarion Call Works for Septet and Octet Michael Berkeley (b. 1948) 1. Clarion Call and Gallop (2013) * [6:42] Berkeley Ensemble Howard Ferguson (1908-1999) Octet, Op. 4 (1933) 2. Moderato [5:34] 2-6 Kathryn Riley violin 3. Allegro scherzoso [3:52] 4. Andantino [5:14] Sophie Mather violin 5. Allegro feroce [6:01] Dan Shilladay viola John Casken (b. 1949) Gemma Wareham cello 6. Blue Medusa (2000/2007) * [10:09] double bass Lachlan Radford Charles Wood (1866-1926) John Slack clarinet Septet (1889) * 7. Allegro moderato [12:10] Andrew Watson bassoon 8. Andante [8:20] Paul Cott horn 9. Scherzo [6:05] 10. With vigour [12:08] About Berkeley Ensemble: ‘This talented group [...] is named after Sir Lennox Berkeley and his son Total playing time [76:15] Michael, and it champions music by them plus that of other British composers which in their view is unjustly neglected. [...] A stimulating evening.’ The Independent * world premiere recordings ‘The refined playing had an impressive sense of style’ Leicester Mercury Echoes of Beethoven first intake of scholars at the newly instituted Royal College of Music (RCM) where he studied ‘That damned thing! I wish it were burned!’ composition with Charles Villiers Stanford, Thus Beethoven referred, with typical one of the principal architects of the so-called bluntness, to his own youthful Septet, the English Musical Renaissance. Born to a tenor continuing popularity of which he felt to in the choir of Armagh’s Church of Ireland be overshadowing his subsequent work. -

Biography – Philip SHEFFIELD – Tenor

Biography – Philip SHEFFIELD – Tenor Philip Sheffield studied at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama and the Royal College of Music before making his professional debut as a soloist in L’incoronazione di Poppea in the Brussel’s Théâtre de la Monnaie. In 2007 he sang Tom Rakewell in Robert Lapage's new production of The Rakes Progress at La Monnaie, made his La Scala debut in Robert Carsen’s controversial production of Candide, took the leading tenor role in Jonathan Dove’s new opera Kwasi and Kwame for OT Rotterdam, sang Eisenstein (Fledermaus) at The Concertgebouw/Amsterdam and Flagey/Brussels and performed Haydn's Die Schöpfung in Firenze, Siena and Perugia with the Orchestra della Toscana. Another highlight of season 07/08 was his appearance at the Opera of Lisbon with the part of the Prince in the world creation of Emmanuel Nunes’ opera “Das Märchen”. During recent seasons he sang Alonso in Tomas Ades The Tempest in a co-production between The Royal Opera House Covent Garden and The Opera du Rhin, a production that went concertant at The Concertgebouw Amsterdam. Furthermore in the contemporary field he created Edward IV in Battistelli’s Richard III (at Vlaamse Opera and at Opera du Rhin, Strasbourg). He interpreted more music by Battistelli as Konzertmeister in Giorgio Battistelli’s Prova d’orchestra for the Vlaamse Opera. He was also cast for the leading role of Crom in Music Theatre Wales new award winning opera The House of the Gods. Other recent highlights included his Japanese debut in the title role of Haydn’s Orlando in Tokyo, revivals of Carsen’s Candide at ENO and in Japan, his debut as Don Jose in concert, Dr. -

Gabriel Jackson Requiem He Vasari Singers Gave the with People Today

Oxford Winter 2008 musicnow32 Gabriel Jackson Requiem he Vasari Singers gave the with people today. We worked closely world premiere of Gabriel on the choice of poems and those which TJackson’s Requiem at St Gabriel ultimately selected for musical Martin-in-the-Fields on Tuesday setting reflect our desire to focus on life 11 November. The Vasari Singers, who renewal rather than death. commissioned the work, have a long The result is a unique blend of tradition of performing and commis- the traditional and the refreshingly sioning new music, and remain at the unfamiliar. Gabriel infuses the whole forefront of the contemporary choral with his luminous and ecstatic writing, music scene. producing a sublime work of true Jeremy Backhouse, Music Director of the profundity and vibrancy. Vasari Singers, and Gabriel Jackson reflect JEREMY BACKHOUSE on the Requiem: Photo: KatieVandyck I had long been an admirer of the choral output of Gabriel Jackson, one of the sit comfortably within the context of a leading composers of his generation, and cathedral Evensong, but that the works had been delighted with his anthem Now could also look beyond any constraints I have known, O Lord, written for our of Liturgy or formal religious doctrine 25th Anniversary in 2005. That encour- to embrace a wider, more ecumenical aged me to approach Gabriel to write us audience; something more humanistic a more extended work and thus the idea perhaps, that might connect more of a Requiem was born. relevantly with multi-cultural, multi-faith societies of the world in the twenty-first I wanted the traditional format to century. -

BERKELEY (1903-1989) Sacred Choral Music Berkeley

REAM.1129 MONO ADD LENNOX BERKELEY (1903-1989) Sacred Choral Music Berkeley (1947) For six solo voices, and chamber orchestra of 12 players 1 I. Stabat Mater dolorosa (5’01”) 2 II. O quam tristis et afflicta (3’38”) 3 III. Quis est homo qui non fleret / IV. Pro peccatis suæ gentis (4’50”) 4 V. Eia Mater, fons amoris (3’33”) 5 VI. Sancta Mater, istud agas / VII. Fac me tecum, pie, flere (4’24”) 6 VIII. Virgo virginum præclara / IX. Fac me plagis vulnerari (5’33”) 7 X. Christe, cum sit hinc exire (5’58”) Mary Thomas (soprano) Barbara Elsy (soprano) Maureen Lehane (contralto) Nigel Rogers (tenor) Christopher Keyte (baritone) Michael Rippon (bass) Ambrosian Singers, chorus-master, John McCarthy Members of the English Chamber Orchestra, leader, Emanuel Hurwitz Conducted by Norman Del Mar From Friends' House, London during the St Pancras Arts Festival BBC Broadcast 1 March 1965 The BBC wordmark and the BBC logo are trade marks of the British Broadcasting Corporation and are used under licence. BBC logo © BBC 1996 c © REAM1129 20 REAM1129 1 ‘Being a Catholic has meant that I feel at home with the Roman liturgy … I felt attracted to these texts because I believed what they were about’.1 This statement by Lennox 8 (1962) Berkeley (1903-1989), taken from an interview with his biographer Peter Dickinson in For soprano, chorus, oboe, horn, cellos, double-bass and organ 1978, helps to account for the passionate commitment and inner strength of the composer’s religious choral writing. Several of his sacred works, including two major Felicity Harrison (soprano) Donald Hunt (organ) examples presented here, are set to Latin texts despite being written for the concert hall BBC Northern Singers & Members of the BBC Northern Orchestra and not intended for inclusion in the Liturgy. -

BBC Radio in the Digital Era (1982 - ) Professor Jeremy Summerly

BBC Radio in the Digital Era (1982 - ) Professor Jeremy Summerly 15 April 2021 On Hallowe’en in 1981, Paul Vaughan became the presenter of Radio 3’s Record Review. Vaughan took over from John Lade (the programme’s founder-presenter) who had presented exactly 1,000 editions of the programme. Lade had led his listeners from 78s to LPs and Vaughan ushered in the CD era. Since its very first episode in 1957, ‘Building a Library’ has been at the heart of Record Review (re-named CD Review from 1998 until 2015). For most of its history ‘Building a Library’ has been a pre-recorded monologue punctuated by comparative musical examples, but on 22 March 2014 it was broadcast as a two-way live interview with presenter Andrew McGregor from a pop-up studio in London’s Southbank Centre. Thus, I was the first contributor to deliver ‘Building a Library’ live (having worked as a freelance contributor to the programme since 1992). On that spring morning in 2014, I chose Trevor Pinnock’s 1993 recording of Mozart’s Coronation Mass over the 1971 version by the London Symphony Orchestra under Sir Colin Davis. A group of dedicated CD Review listeners had congregated around the BBC pod to witness the live broadcast of the programme, and during the course of the segment they started to react to my analytical observations with muted applause and/or good-natured hisses of disapproval. That direct contact with the CD Review audience was a wonderful experience, albeit a predictably confirmatory one: Radio 3’s audience has an average age of around 60 years old, and that was borne out that morning in the Royal Festival Hall foyer. -

2018 Programme Absolutely Final Draft.Indd

MUSIC on the mind Little Venice Music Fesival 2018 Programme Become a Festival Friend Little Venice Music Festival Founded in 2002 by Sylvia Rhys- Honorary Patrons Thomas, the Little Venice Music Michael Berkeley, CBE Festival has always been indebted David Campbell to its friends and supporters, who Miss Joanna David donate what they can to help Edward Fox, OBE present an exhilarating annual Jill Gomez, Countess of Northesk weekend of chamber music. Sir Sydney Kentridge QC Festival curators the Berkeley Festival Friends Ensemble launched a new G Adams supporter scheme in 2016 to Mr I Adams ensure the festival‘s future, and Fr G Bradley as a registered charity, if you are Miss C Castle a registered UK tax payer we are J Lloyd-Davies able to make every donation go Mr M Green 25% further. M Lugon Mr R Pye Join as a Friend, Supporter or Mr A Reis e Sousa Benefactor today, from as little Mr & Mrs D Thompson as £35 a year, to help us develop Ms J Thompson and guarantee the future of this Mr M Wood uniquely community-focussed festival. In return for your The festival would like to thank: generosity, receive our thanks and Fr Gary, Karen Peakman and all at St. benefits to enhance your festival Saviour’s Church experience, including advance CAVATINA Chamber Music Trust information, priority booking and The Garrick Charitable Trust exclusive access to festival artists The Samuel Gardner Memorial Trust through open rehearsals and Westminster City Council Ward Trust receptions. The Berkeley Ensemble Trustees Gavin Compton For more information, see the Joy Lawson friends scheme leaflets, available David Motion at the ticket desk, or the festival Our team of festival volunteers, whose website littlevenice-mf.com. -

Via Panorâmica 3

Via Panorâmica 3 III série. 2014 Revista An Electronic Electrónica Journal of de Estudos Anglo-American Anglo-Americanos Studies ISSN: 1646-4728 Via Panorâmica 3 III série. 2014 Title: Via Panorâmica: Revista de Estudos Anglo-americanos E-Journal of Anglo-American Studies Director: Gualter Cunha Executive Editors: Miguel Ramalhete Gomes | Márcia Lemos Editor: Universidade do Porto. Faculdade de Letras ISSN: 1646-4728 Via Panorâmica é uma revista eletrónica que respeita integralmente os critérios da política do acesso livre à informação. Via Panorâmica is an open access electronic journal that follows all the criteria of OA publishing policy. Via Panorâmica 3 III série. 2014 Revista Electrónica de An Electronic Journal of Estudos Anglo-Americanos Anglo-American Studies Sumário | Contents A prefatory note Miguel ramalhete Gomes William Morris and the Pre-Raphaelites Maria Cândida Zamith Silva “What a wonderful piece of work is a woman!”: Orlando and The Enigma of the Sexes Maria de Deus Duarte A Safe Haven for Elizabeth Bishop Sílvia Maria Guerra Anastácio O Papel da Grandmother em “A Good Man is Hard to Find” Narayana de Deus Nogueira Bregagnoli Science of Literature: The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, Volumes IV and V, and the Making of Irish Feminism Zuzanna Sanches The Translation of Silence: The Interdisciplinary Nature of A Book of Silence and its Implications for Translation Jorge Manuel Costa Almeida e Pinho Visual Popular Culture and Political Power José Carlos del Ama and Ismael López Medel “As Principais Correntes do Pensamento Americano”, Irwin Shaw Tradução de Carla Morais Pires A Prefatory Note Miguel Ramalhete │ University of Porto In 2014, Via Panorâmica offers two issues: its current annual issue and a special issue composed of selected papers presented at “Relational Forms II: An International Conference on Literature, Science and the Arts”, held in December 2012 at the Faculty of Arts of the University of Porto.