Cold War Fictions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston International Antiquarian Book Fair 2019

BOSTON INTERNATIONAL ANTIQUARIAN BOOK FAIR november 15–17, 2019 | hynes convention center | booth 410 friday, 4pm–8pm | saturday, noon–7pm | sunday, noon–5pm Anthony Bell AFTALION, Albert. Les Crises périodiques de ANTHONY, Susan B. History of Woman Suffrage. surproduction. Paris: Marcel Rivière, 1913 Rochester: Susan B. Anthony, 1886 & 1902 first edition, very scarce: one of the earliest statements of first editions, presentation copies of volumes III and IV the acceleration principle. 2 vols., modern blue cloth, preserving of the “bible” of the women’s suffrage campaign, the only two original paper wrappers and spines. volumes published by Anthony herself; inscribed in both by the $7,500 [135866] author on the occasion of her 85th birthday to her cousin Joshua. 2 vols., original maroon cloth; an excellent set. $15,750 [132954] BELL, Jocelyn; et al. Observation of a Rapidly Pulsating Radio Source. [Offprint from:] Nature, Vol. 217, No. 5130, pp. 709–713, February 24, 1968. London: Macmillan, 1968 first edition, the extremely rare offprint, of the landmark paper which announced the discovery of pulsars, co-authored by British astrophysicist Jocelyn Bell, her thesis supervisor Antony Hewish, and three others. 4to, original blue printed stiff wrappers. Bound with 18 other offprints in contemporary red cloth, all fine or near-fine. $9,800 [131009] Anthony Cather Dickens, The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club BORGES, Jorge Luis. Luna de enfrente. Buenos Aires: DARWIN, Charles. On the Origin of Species. London: Editorial Proa, 1925 John Murray, 1860 first edition, first printing, one of 300 copies of Jorge Luis second edition, the usual issue correctly dated 1860 on the Borges’s scarce second collection of poetry. -

What Literature Knows: Forays Into Literary Knowledge Production

Contributions to English 2 Contributions to English and American Literary Studies 2 and American Literary Studies 2 Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Kai Merten (eds.) Merten Kai / What Literature Knows This volume sheds light on the nexus between knowledge and literature. Arranged What Literature Knows historically, contributions address both popular and canonical English and Antje Kley US-American writing from the early modern period to the present. They focus on how historically specific texts engage with epistemological questions in relation to Forays into Literary Knowledge Production material and social forms as well as representation. The authors discuss literature as a culturally embedded form of knowledge production in its own right, which deploys narrative and poetic means of exploration to establish an independent and sometimes dissident archive. The worlds that imaginary texts project are shown to open up alternative perspectives to be reckoned with in the academic articulation and public discussion of issues in economics and the sciences, identity formation and wellbeing, legal rationale and political decision-making. What Literature Knows The Editors Antje Kley is professor of American Literary Studies at FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany. Her research interests focus on aesthetic forms and cultural functions of narrative, both autobiographical and fictional, in changing media environments between the eighteenth century and the present. Kai Merten is professor of British Literature at the University of Erfurt, Germany. His research focuses on contemporary poetry in English, Romantic culture in Britain as well as on questions of mediality in British literature and Postcolonial Studies. He is also the founder of the Erfurt Network on New Materialism. -

Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press 2014

Jan 14 #1 Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press Sherlockians (and Holmesians) gathered in New York to celebrate the Great Detective's 160th birthday during the long weekend from Jan. 15 to Jan. 19. The festivities began with the traditional ASH Wednesday dinner sponsored by The Adventuresses of Sherlock Holmes at O'Casey's and continued with the Christopher Morley Walk led by Jim Cox and Dore Nash on Thursday morning, followed by the usual lunch at McSorley's. The Baker Street Irregulars' Distinguished Speaker at the Midtown Executive Club on Thursday evening was James O'Brien, author of THE SCIENTIFIC SHER- LOCK HOLMES: CRACKING THE CASE WITH SCIENCE & FORENSICS (2013); the title of his talk was "Reassessing Holmes the Scientist", and you will be able to read his paper in the next issue of The Baker Street Journal. The William Gillette Luncheon at Moran's was well attended, as always, and the Friends of Bogie's at Baker Street (Paul Singleton, Sarah Montague, and Andrew Joffe) entertained their audience with a tribute to an aged Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson. The luncheon also was the occasion for Al Gregory's presentation of the annual Jan Whimsey Award (named in memory of his wife Jan Stauber) honoring the most whimsical piece in The Serpentine Muse last year; the winners (Susan Rice and Mickey Fromkin) received certificates and shared a check for the Canonical sum of $221.17. And Otto Penzler's tradi- tional open house at the Mysterious Bookshop provided the usual opportuni- ties to browse and buy. The Irregulars and their guests gathered for the BSI annual dinner at the Yale Club, where John Linsenmeyer proposed the preprandial first toast to Marilyn Nathan as The Woman. -

The Concept of Irony in Ian Mcewan's Selected Literary Works

Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci Filozofická fakulta Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Bc. Eva Mádrová Concept of Irony in Ian McEwan’s Selected Literary Works Diplomová práce PhDr. Libor Práger, Ph.D. Olomouc 2013 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diplomovou práci na téma “Concept of Irony in Ian McEwan’s Selected Literary Works” vypracovala samostatně pod odborným dohledem vedoucího práce a uvedla jsem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V Olomouci dne Podpis I would like to thank my supervisor PhDr. Libor Práger, Ph.D. for his assistance during the elaboration of my diploma thesis, especially for his valuable advice and willingness. Table of contents Introduction 6 1. Ian McEwan 7 2. Methodology: Analysing irony 8 2.1 Interpreter, ironist and text 8 2.2 Context and textual markers 10 2.3 Function of irony 11 2.4 Postmodern perspective 12 3. Fiction analyses 13 3.1 Atonement 13 3.1.1 Family reunion ending as a trial of trust 13 3.1.2 The complexity of the narrative: unreliable narrator and metanarrative 14 3.1.3 Growing up towards irony 17 3.1.4 Dramatic encounters and situations in a different light 25 3.2 The Child in Time 27 3.2.1 Loss of a child and life afterwards 27 3.2.2 The world through Stephen Lewis’s eyes 27 3.2.3 Man versus Universe 28 3.2.4 Contemplation of tragedy and tragicomedy 37 3.3 The Innocent 38 3.3.1 The unexpected adventures of the innocent 38 3.3.2 The single point of view 38 3.3.3 The versions of innocence and virginity 40 3.3.4 Innocence in question 48 3.4 Amsterdam 50 3.4.1 The suicidal contract 50 3.4.2 The multitude -

Intertextuality in Ian Mcewan's Selected Novels

1 Intertextuality in Ian McEwan's Selected Novels Assist. Prof. Raad Kareem Abd-Aun, PhD Dijla Gattan Shannan (M.A. Student) Abstract The term intertextuality is coined by poststructuralist Julia Kristeva, in her essay “Word, Dialogue and Novel” (1969). The underlying principle of intertextuality is relationality and lack of independence. In this paper, this technique (intertextuality) will be discussed in Ian McEwan's selected novels. The novels are Enduring Love (1997), Atonement (2001), and Sweet Tooth (2012). Key Words: intertextuality, McEwan, Enduring Love, Atonement, Sweet Tooth. التناص في أعمال روائية مختارة ﻹيان مكيون أ.م. د. رعد كريم عبد عون دجلة كطان شنان أستخدم مصطلح التناص ﻷول مرة من قبل الناقدة جوليا كرستيفا في مقالتها )الكلمة و الحوار و الرواية( عام 1969. إن المبدأ الرئيس خلف التناص هو العﻻقة وعدم وجود اﻹستقﻻلية. وفي هذا البحث، ُدرست هذه التقنية في روايات مختارة ﻹيان مكيون، والروايات هي الحب اﻷبدي )1997( و الغفران )2001( و سويت تووث )2012(. الكلمات المفتاحية: التناص؛ مكيون؛ الحب اﻷبدي؛ الغفران؛ سويت تووث. 2 Intertextuality in Ian McEwan's Selected Novels Ian McEwan (1948) is one of the most significant British writers since the 1970s, this is due his way of the link between morality and the novel for a whole generation, in ways that befit the historical pressures of their time. This makes his novels have a significant form of cultural expression McEwan’s early works are characterized by self – ambiguity in which he is tackling important social themes within the fictional scenario. His early narrative is described as “snide and bored”, or as “acutely dysfunctional or the abusive”, at other times as “inexplicaply lawless”. -

Michael Berkeley and David Malouf's Rewriting of Jane Eyre: an Operatic and Literary Palimpsest*

CHAPTER 6 Michael Berkeley and David Malouf’s Rewriting of Jane Eyre: An Operatic and Literary Palimpsest* Jean-Philippe Heberlé English composer Michael Berkeley (born 1948) is the son of Lennox Berkeley (1903–1989), himself a composer of instrumental music and operas including, for instance, A Dinner Engagement (1955) and Ruth (1955–56). To this day, Michael Berkeley has written three operas and is currently working on a new operatic project based on Ian McEwan’s novel Atonement (2001). For his first two operas (Baa Baa Black Sheep, 1993, and Jane Eyre, 2000), he collaborated with acclaimed Australian novelist David Malouf (born 1934). This chap- ter addresses Berkeley’s second opera, Jane Eyre, a chamber opera1 premiered at the Cheltenham Music Festival on June 30, 2000. The opera by David Malouf and Michael Berkeley appears to be an oper- atic and literary palimpsest in which Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre is compressed and distorted into a concentrated operatic drama of little more than 70 minutes.2 Five characters form the cast, and the storyline focuses exclusively on the events at Thornfield. In this intertextual3 and intermedial4 analysis of Berkeley and Malouf’s operatic adapta- tion of Jane Eyre, a study of the text and the music reveals whether the librettist and the composer focalized or not on particular elements and episodes of the original novel. The artists at times amended, dis- torted, or retained elements of the novel, allowing their new work to interpret Charlotte Brontë’s novel’s psychologically developed char- acters and its gothic atmosphere. Finally, the opera and its libretto function metadramatically. -

Michael Berkeley Selected Reviews

Michael Berkeley Selected Reviews Winter Fragments (Chamber Music Recording) Resonus Classics RES10223 (September 2018) “Stylistically ranging from the plainchant-inspired Clarinet Quintet (1983) to the sensuous and Satie-like Seven (2007), to the jostling intensity of Catch Me If You Can (1994), it shows Berkeley at his exploratory and individualistic best, free to follow his instinct, tonal or expressionistic” – Fiona Maddocks, The Guardian “Even when working with large-scale forces such as opera and music theatre, Michael Berkeley's style and expression remain attuned to the more intimate nuances of chamber music. Perhaps this is because the chamber context provides such an effective vehicle for one of his music's most distinctive features - the often dichotomous interplay between the individual and the group... the Berkeley Ensemble, directed by Dominic Grier, are excellent throughout - entirely at one with the music of their namesake composer” – Pwyll ap Sion, Gramophone “There’s contrast aplenty – Catch Me If You Can (1994) a feisty, frenetic triptych, the gentle, self-echoing, harp-centred Seven (2007) pregnant with a pensiveness that collides late Mahler with Satie at his most subdued. The Clarinet Quintet (1983) is spun from sinewy, twisting strands contrasting the playful impetuosity and dark-hued luminosity of John Slack’s clarinet to end in a moment of sublimely subdued beauty. 2010’s Rilke-setting Sonnet for Orpheus and the seven-part song-cycle Winter Fragments (1996) – both benefiting from Fleur Barron’s ardent mezzo – -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

The Sense and Sensibility in Later Novels of Ian Mcewan (Bachelor’S Thesis)

Palacký University in Olomouc Philosophical Faculty Department of English and American Studies The Sense and Sensibility in Later Novels of Ian McEwan (Bachelor’s thesis) Eva Pudová English Philology - Journalism Supervisor: PhDr. Libor Práger, PhD. Olomouc 2016 I confirm that I wrote this thesis myself and integrated corrections and suggestions of improvement of my supervisor. I also confirm that the thesis includes complete list of sources and literature cited. In Olomouc .................................. I would like to thank my supervisor, PhDr.Libor Práger, PhD, for his support, assistance and advice. Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 5 1. Ian McEwan ..................................................................................................... 7 2. Other works...................................................................................................... 9 3. Critical perspective ........................................................................................ 11 4. Characters ...................................................................................................... 14 4.1. Realness of the characters ...................................................................... 14 4.2. Character differences and similarities .................................................... 16 5. -

S POST-MILLENNIAL NOVELS ZDENĚK BERAN Ian Mcewan

2016 ACTA UNIVERSITATIS CAROLINAE PAG. 123–135 PHILOLOGICA 1 / PRAGUE STUDIES IN ENGLISH METAFICTIONALITY, INTERTEXTUALITY, DISCURSIVITY: IAN MCEWAN ’ S POST-MILLENNIAL NOVELS ZDENĚK BERAN ABSTRACT In his twenty-first-century novels, Atonement, Saturday, Solar and Sweet Tooth, Ian McEwan makes ample use of narrative strategies characteris- tic of postmodernist writing, such as metafictionality, intertextuality and discursive multiplicity. This article discusses how this focus distinguish- es his recent novels from earlier ones. Thus Sweet Tooth is read as a text which includes the author ’ s attempt to revise his own shorter texts from the onset of his career in the mid-1970s. The use of parallelisms and alle- gory in McEwan ’ s 1980s novels The Child in Time and The Innocent is then contrasted with more complex strategies in Saturday and Solar. Special attention is given to the thematization of the role of discourse in Solar; it is argued that the novel is not just a satire on modern science and its corrup- tion by commercialization but also a reflection of “ontological relativism” as a product of prevailing contemporary discourse formations. Keywords: contemporary British novel; Ian McEwan; discourse; Foucault; intertextuality; metafiction Ian McEwan ’ s recent novel, Sweet Tooth (2012), reveals the author ’ s proclivity for the use of metafictional writing at its most entangled and transgressive best. After more than three successful decades on the British literary scene,1 McEwan has here offered his 1 The outstanding position of Ian McEwan as one of the most successful contemporary English writers can be documented by the many literary awards his work has received across decades: His early col- lection of short stories First Love, Last Rites (1975) won the Somerset Maugham Award in 1976. -

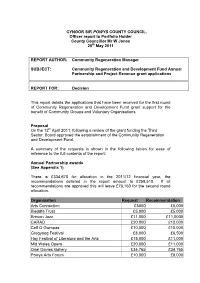

Community Regeneration and Development Fund Annual Partnership and Project Revenue Grant Applications

CYNGOR SIR POWYS COUNTY COUNCIL. Officer report to Portfolio Holder County Councillor Mr W Jones 25 th May 2011 REPORT AUTHOR: Community Regeneration Manager SUBJECT: Community Regeneration and Development Fund Annual Partnership and Project Revenue grant applications REPORT FOR: Decision This report details the applications that have been received for the first round of Community Regeneration and Development Fund grant support for the benefit of Community Groups and Voluntary Organisations. Proposal On the 12 th April 2011, following a review of the grant funding the Third Sector, Board approved the establishment of the Community Regeneration and Development Fund. A summary of the requests is shown in the following tables for ease of reference to the full contents of the report: Annual Partnership awards (See Appendix 1) There is £334,670 for allocation in the 2011/12 financial year, the recommendations detailed in the report amount to £258,510. If all recommendations are approved this will leave £76,160 for the second round allocation. Organisation Request Recommendation Arts Connection £5000 £5,000 Bleddfa Trust £5,000 £5,000 Brecon Jazz £11,000 £11,0000 CARAD £20,000 £12,000 Celf O Gwmpas £10,000 £10,000 Gregynog Festival £8,000 £6,500 Hay Festival of Literature and the Arts £15,000 £11,000 Mid Wales Opera £20,000 £11,000 Oriel Davies Gallery £34,765 £34,765 Powys Arts Forum £10,000 £8,000 Powys Association Of Voluntary Organisations £30,000 £30,000 Powys Leisure Services £24,000 £12,000 Play Montgomeryshire £15,000 £15,000 Powys Federation of Women’s Institutes £2,400 £2,400 Presteigne Festival of the Arts £10,000 £9,000 Presteigne Shire Hall Museum Trust Ltd £7,500 £7,500 Wyeside Arts Centre £47,025 £47,025 Llandrindod Wells Victorian Festival £11,000 £11,000 Wales Pre-school Playgroup Assoc. -

Annual Report October 2011–September 2013

HOUSE OF LORDS APPOINTMENTS COMMISSION ANNUAL REPORT October 2011 to September 2013 House of Lords Appointments Commission Page 3 Contents Section 1: The Appointments Commission 5 Section 2: Appointments of non-party-political peers 8 Section 3: Vetting party-political nominees 11 Annex A: Biographies of the Commission 14 Annex B: Individuals vetted by the Commission 16 and appointed to the House of Lords [Group photo] Page 4 Section 1 The Appointments Commission 1. In May 2000 the Prime Minister established the House of Lords Appointments Commission as an independent, advisory, non-departmental public body. Commission Membership 2. The Commission has seven members, including the Chairman. Three members represent the main political parties and ensure that the Commission has expert knowledge of the House of Lords. The other members, including the Chairman, are independent of government and political parties. The independent members were appointed in October 2008 by open competition, in accordance with the code of the Commissioner for Public Appointments. The party-political members are all members of the House of Lords and were nominated by the respective party leader in November 2010 for three year terms. 3. The terms of all members therefore come to an end in the autumn of 2013. 4. Biographies of the Commission members can be seen at Annex A. 5. The Commission is supported by a small secretariat at 1 Horse Guards Road, London SW1A 2HQ. Role of the House of Lords Appointments Commission 6. The role of the Commission is to: make recommendations for the appointment of non-party-political members of the House of Lords; and vet for propriety recommendations to the House of Lords, including those put forward by the political parties and Prime Minister.