Architecture, Sculptures and Murals in Southern Shanxi Under the Yuan Dynasty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Xiaohe 1': a New Walnut Cultivar with High Fruit Setting Rate Of

HORTSCIENCE 55(12):2047–2051. 2020. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI15340-20 ing, androgenic type, and high yield, which are similar to the characteristics of ‘Xiaohe 1’. ‘Xiaohe 1’: A New Walnut Cultivar The cultivar Xiaohe 1 presented high- yielding potential despite late-frost incidents with High Fruit Setting Rate of after the initial budding. For example, after a province-wide late-frost incident in 2018, the Secondary Bud Germination after the cultivar Xiaohe 1 showed stronger resistance to below-freezing temperature, a higher fruit set rate after secondary emergence of acces- Harm of Late Frost sory and other buds, and better overall traits Jing Wu, Qi He, Caihong Zhang, and Gui Wang than the control cultivars Liaoning 1 and Shanxi Academy of Forestry Sciences, Taiyuan, Shanxi 030012, China Luguang. Additional index words. breeding, late frost hazard, secondary bud germination, walnut Description and Performance The tree stand of ‘Xiaohe 1’ is semi- Walnut (Juglans regia L.), a deciduous the Xinjiang Kashgar region, and in the dwarf, with a spreading growth habit and tree in the Juglandaceae family, is a forest central and southern parts of Shanxi Province moderate growth rate. The height of a 6- tree species that has a long cultivation history it caused freezing damage to walnut trees and year-old tree is four-fifths that of ‘Liaoning and wide distribution in China because of its decimated production in select areas (Liu 1’. The fruit branches are short and thick, economic importance (Pei and Lu, 2011). et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2007). The damage with an average length of 16.4 cm and an China accounts for more than 50% of the caused by late frost in 2013 resulted in average diameter of 0.9 cm. -

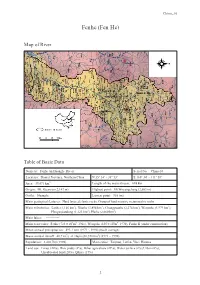

Fenhe (Fen He)

China ―10 Fenhe (Fen He) Map of River Table of Basic Data Name(s): Fenhe (in Huanghe River) Serial No. : China-10 Location: Shanxi Province, Northern China N 35° 34' ~ 38° 53' E 110° 34' ~ 111° 58' Area: 39,471 km2 Length of the main stream: 694 km Origin: Mt. Guancen (2,147 m) Highest point: Mt.Woyangchang (2,603 m) Outlet: Huanghe Lowest point: 365 (m) Main geological features: Hard layered clastic rocks, Group of hard massive metamorphic rocks Main tributaries: Lanhe (1,146 km2), Xiaohe (3,894 km2), Changyuanhe (2,274 km2), Wenyuhe (3,979 km2), Honganjiandong (1,123 km2), Huihe (2,060 km2) Main lakes: ------------ 6 3 6 3 Main reservoirs: Fenhe (723×10 m , 1961), Wenyuhe (105×10 m , 1970), Fenhe II (under construction) Mean annual precipitation: 493.2 mm (1971 ~ 1990) (basin average) Mean annual runoff: 48.7 m3/s at Hejin (38,728 km2) (1971 ~ 1990) Population: 3,410,700 (1998) Main cities: Taiyuan, Linfen, Yuci, Houma Land use: Forest (24%), Rice paddy (2%), Other agriculture (29%), Water surface (2%),Urban (6%), Uncultivated land (20%), Qthers (17%) 3 China ―10 1. General Description The Fenhe is a main tributary of The Yellow River. It is located in the middle of Shanxi province. The main river originates from northwest of Mt. Guanqing and flows from north to south before joining the Yellow River at Wanrong county. It flows through 18 counties and cities, including Ningwu, Jinle, Loufan, Gujiao, and Taiyuan. The catchment area is 39,472 km2 and the main channel length is 693 km. -

Impact of Coal Mining on Karst Water System in North China

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Procedia Earth and Planetary Science 3 ( 2011 ) 293 – 302 2011 Xican International Conference on Fine Geological Exploration and Groundwater & Gas Hazards Control in Coal Mines Impact of Coal Mining on Karst Water System in North China Xiangqing Fang*, Yaojun Fu Hydrogeology Bureau of China Nat ion al Administration of Coal Geology, Handan 056004, China Abstract Based on a large number of data, the paper analysed the influence factors of coal mining for the karst water system in north China, used analytic hierarchy process (AHP) for evaluation of the effect of coal mining on the karst water system, and divided influence degree subareas of State-planed 21 coal mining areas. We also come up with some suggestions on prevention and control measures of principle according to the different influence degrees. ©© 20112011 Published Published by by Elsevier Elsevier Ltd. Ltd. Selection Selection and and/or peer-review peer-review under under responsibility responsibility of China of Xi’an Coal Research Society Institute of China Coal Technology & Engineering Group Corp Keywords: karst-water system in north China, influence degree, prevention and control measures; North China type coalfield and the karst water system in the north are inseparable, there exists three superposition relationships [1]: monoclinal structure, synclinal structure and block-faulting structure. Karst water system in the north is characterized by large scales, numerous components of water resources, the complexity of transformation between water resources, coexistence of water and coal and so on. The karst water resource in the north is not only important water resource, but also is threatening the coal resources. -

Master for Quark6

Special Feature s e v i a t Realisms within Conundrum c n i e h The Personal and Authentic Appeal in Jia Zhangke’s Accented Films (1) p s c r e ESTHER M. K. CHEUNG p With persistent efforts on constructing personal and collective memories arising from the unprecedented transformations in post-socialist China, Jia Zhangke has produced an ensemble of realist films with an impressive personal and authentic appeal. This paper examines how his films are characterised by a variety of accents, images of authenticity, a quotidian ambience, and a new sense of materiality within the local-global nexus. Within a tripartite model of truth, identity, and performance, Jia’s oeuvres demonstrate the powerful performativity of different modes of realism arising out of a state of conundrum when China undergoes a transition from planned economy into wholesale marketisation and globalisation. The appeal of Jia Zhangke’s fined to documentary realism. His films serve to write up a accented cinema history of his generation: rom his first feature Xiao Wu (aka The Pickpocket , I made these films because I wanted to compensate 1997) to 24 City (2008), Jia Zhangke’s films have for what was not fulfilled. I must also emphasise that Fbeen characterised by an impressive personal and au - apart from the realist mode, there are other kinds of thentic appeal. As viewers, in about a decade’s time we have representation that can be called “visual memory”; for observed an ongoing process of the director’s negotiation example, Dali’s surrealist images in the early twentieth with realism as a mode of film representation. -

Piece Mold, Lost Wax & Composite Casting Techniques of The

Piece Mold, Lost Wax & Composite Casting Techniques of the Chinese Bronze Age Behzad Bavarian and Lisa Reiner Dept. of MSEM College of Engineering and Computer Science September 2006 Table of Contents Abstract Approximate timeline 1 Introduction 2 Bronze Transition from Clay 4 Elemental Analysis of Bronze Alloys 4 Melting Temperature 7 Casting Methods 8 Casting Molds 14 Casting Flaws 21 Lost Wax Method 25 Sanxingdui 28 Environmental Effects on Surface Appearance 32 Conclusion 35 References 36 China can claim a history rich in over 5,000 years of artistic, philosophical and political advancement. As well, it is birthplace to one of the world's oldest and most complex civilizations. By 1100 BC, a high level of artistic and technical skill in bronze casting had been achieved by the Chinese. Bronze artifacts initially were copies of clay objects, but soon evolved into shapes invoking bronze material characteristics. Essentially, the bronze alloys represented in the copper-tin-lead ternary diagram are not easily hot or cold worked and are difficult to shape by hammering, the most common techniques used by the ancient Europeans and Middle Easterners. This did not deter the Chinese, however, for they had demonstrated technical proficiency with hard, thin walled ceramics by the end of the Neolithic period and were able to use these skills to develop a most unusual casting method called the piece mold process. Advances in ceramic technology played an influential role in the progress of Chinese bronze casting where the piece mold process was more of a technological extension than a distinct innovation. Certainly, the long and specialized experience in handling clay was required to form the delicate inscriptions, to properly fit the molds together and to prevent them from cracking during the pour. -

Seon Dialogues 禪語錄禪語錄 Seonseon Dialoguesdialogues John Jorgensen

8 COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM 8 SEON DIALOGUES 禪語錄禪語錄 SEONSEON DIALOGUESDIALOGUES JOHN JORGENSEN COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM VOLUME 8 禪語錄 SEON DIALOGUES Collected Works of Korean Buddhism, Vol. 8 Seon Dialogues Edited and Translated by John Jorgensen Published by the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism Distributed by the Compilation Committee of Korean Buddhist Thought 45 Gyeonji-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul, 110-170, Korea / T. 82-2-725-0364 / F. 82-2-725-0365 First printed on June 25, 2012 Designed by ahn graphics ltd. Printed by Chun-il Munhwasa, Paju, Korea © 2012 by the Compilation Committee of Korean Buddhist Thought, Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism This project has been supported by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, Republic of Korea. ISBN: 978-89-94117-12-6 ISBN: 978-89-94117-17-1 (Set) Printed in Korea COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM VOLUME 8 禪語錄 SEON DIALOGUES EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY JOHN JORGENSEN i Preface to The Collected Works of Korean Buddhism At the start of the twenty-first century, humanity looked with hope on the dawning of a new millennium. A decade later, however, the global village still faces the continued reality of suffering, whether it is the slaughter of innocents in politically volatile regions, the ongoing economic crisis that currently roils the world financial system, or repeated natural disasters. Buddhism has always taught that the world is inherently unstable and its teachings are rooted in the perception of the three marks that govern all conditioned existence: impermanence, suffering, and non-self. Indeed, the veracity of the Buddhist worldview continues to be borne out by our collective experience today. -

Preparing the Small Cities and Towns Development Demonstration Sector Projects

Technical Assistance Report Project Number: 40641 July 2007 People’s Republic of China: Preparing the Small Cities and Towns Development Demonstration Sector Projects CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 11 July 2007) Currency Unit – yuan (CNY) CNY1.00 = $0.1319 $1.00 = CNY7.5835 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank DFR – draft final report DMF – design and monitoring framework EA – executing agency EIA – environmental impact assessment EMP – environmental management plan FSR – feasibility study report HPG – Hebei provincial government IA – implementing agency LPG – Liaoning provincial government PMO – project management office PPMS – project performance monitoring system PRC – People’s Republic of China RP – resettlement plan SEIA – summary environmental impact assessment SPG – Shanxi provincial government TA – technical assistance TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE CLASSIFICATION Targeting Classification – Targeted intervention (MDG) Sectors – Multisector (water supply, sanitation and waste management, transport and communication, energy, education) Subsectors – Water supply and sanitation, waste management, roads and highways, energy transmission and distribution, technical education, vocational training and skills development Themes – Inclusive social development, Sustainable economic growth, environmental sustainability Subthemes – Human development, fostering physical infrastructure development, urban environmental improvement NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. Vice President C. Lawrence Greenwood, Jr., Operations Group 2 Director General H.S. Rao, East Asia Department (EARD) Director R. Wihtol, Social Sectors Division, EARD Team leader A. Leung, Principal Urban Development Specialist, EARD Team members M. Gupta, Social Development Specialist (Safeguards), EARD S. Popov, Senior Environment Specialist, EARD T. Villareal, Urban Development Specialist, EARD W. Walker, Social Development Specialist, EARD J. Wang, Project Officer (Urban Development and Water Supply), People’s Republic of China Resident Mission, EARD L. -

People's Republic of China: Shanxi Road Development II Project

Completion Report Project Number: 34097 Loan Number: 1967 August 2008 People’s Republic of China: Shanxi Road Development II Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit – yuan (CNY) At Appraisal At Project Completion (14 November 2002) (as of 6 March 2008) CNY1.00 = $0.1208 $0.14047 $1.00 = CNY8.277 CNY7.119 ABBREVIATIONS AADT – average annual daily traffic ADB – Asian Development Bank CSE – chief supervision engineer CSEO – chief supervision engineer office DCSE – deputy chief supervision engineer EIA – environmental impact assessment EIRR – economic internal rate of return FIRR – financial internal rate of return GDP – gross domestic product HDM-4 – highway design and maintenance standards model, version 4 ICB – international competitive bidding IDC – interest and other charges during construction IEE – initial environmental examination IRI – international roughness index MOC – Ministry of Communications NCB – national competitive bidding NTHS – national trunk highway system O&M – operation and maintenance PCR – project completion review PPMS – project performance management system PRC – People’s Republic of China PRIS – poverty reduction impact study PRMP – poverty reduction monitoring program REO – resident engineer office RP – resettlement plan SCD – Shanxi Communications Department SCF – standard conversion factor SEIA – summary environmental impact assessment SEPA – State Environment Protection Administration SFB – Shanxi Finance Bureau SHEC – Shanxi Hou-yu Expressway Construction Company Limited SKCC – Shaanxi Kexin Consultant Company SPG – Shanxi provincial government VOC – vehicle operating cost YWNR – Yuncheng Wetlands Nature Reserve WEIGHTS AND MEASURES mu – A traditional land area measurement, it is equivalent to 666.66 square meters, or 0.1647 acres, or 0.066 of a hectare. m/km – meters per kilometer mg/m3 – milligram per meter cube p.a. -

Buddhist College of Singapore in Affiliation To

Curriculum of Master of Arts Degree in Buddhist Studies (International Program) Buddhist College of Singapore in Affiliation to Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University Revised Curriculum January 2020 Kong Meng San Phor Kark See Monastery Buddhist College of Singapore, 88 Bright Hill Road, Singapore 574117 Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University & Buddhist College of Singapore Master of Arts Program in Buddhist Studies (International Program) Revised Curriculum 2020 Institution’s Title : Buddhist College of Singapore in Affiliation with Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University Faculty/ Department: Buddhist College of Singapore Section 1 General Information 1. Code and Title of Curriculum 2. Code: English: Master of Arts in Buddhist Studies (International Program) 2. Title of Degree Full Title (English) : Master of Arts (Buddhist Studies) Abbreviation (English) :M.A. (Buddhist Studies) 3. Major Field - None - 4. Total Credits 39 Credits 5. Type of Curriculum 5.1 Level Master’s Degree of two-years’ course 5.2 Medium of Instruction English/Chinese language is used as a medium, including English/Chinese documents, textbooks and general books. 5.3 Admission Local and foreign students who have completed all fields of Bachelor’s Degree and are able to use English/Chinese listening, speaking, reading and writing as well as other qualifications designated 5.4 Collaboration with Other Institutions It is a specific curriculum of the university. 5.5Type of Conferred Degree Only one degree conferred for this program. 6. Status and the Approval of Curriculum 6.1 It is the 2019 revised curriculum which is about to be available in academic year 2010 TQF 2 Curriculum of Master of Arts Program in Buddhist Studies (International Program) 2 onward 6.2 The Revised Committee of the Curriculum Development has consensually approved this curriculum at the meeting ____________, on _27 March, 2019. -

82031272.Pdf

journal of palaeogeography 4 (2015) 384e412 HOSTED BY Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect journal homepage: http://www.journals.elsevier.com/journal-of- palaeogeography/ Lithofacies palaeogeography of the Carboniferous and Permian in the Qinshui Basin, Shanxi Province, China * Long-Yi Shao a, , Zhi-Yu Yang a, Xiao-Xu Shang a, Zheng-Hui Xiao a,b, Shuai Wang a, Wen-Long Zhang a,c, Ming-Quan Zheng a,d, Jing Lu a a State Key Laboratory of Coal Resources and Safe Mining, School of Geosciences and Surveying Engineering, China University of Mining and Technology (Beijing), Beijing 100083, China b Hunan Provincial Key Laboratory of Shale Gas Resource Utilization, Hunan University of Science and Technology, Xiangtan 411201, Hunan, China c No.105 Geological Brigade of Qinghai Administration of Coal Geology, Xining 810007, Qinghai, China d Fujian Institute of Geological Survey, Fuzhou 350013, Fujian, China article info abstract Article history: The Qinshui Basin in the southeastern Shanxi Province is an important area for coalbed Received 7 January 2015 methane (CBM) exploration and production in China, and recent exploration has revealed Accepted 9 June 2015 the presence of other unconventional types of gas such as shale gas and tight sandstone Available online 21 September 2015 gas. The reservoirs for these unconventional types of gas in this basin are mainly the coals, mudstones, and sandstones of the Carboniferous and Permian; the reservoir thicknesses Keywords: are controlled by the depositional environments and palaeogeography. This paper presents Palaeogeography the results of sedimentological investigations based on data from outcrop and borehole Shanxi Province sections, and basin-wide palaeogeographical maps of each formation were reconstructed Qinshui Basin on the basis of the contours of a variety of lithological parameters. -

LỊCH SỬ PHẬT VÀ BỒ TÁT (Phan Thượng Hải)

LỊCH SỬ PHẬT VÀ BỒ TÁT (Phan Thượng Hải) Lịch sử Phật Giáo bắt đầu ở Ấn Độ. Từ Phật Giáo Nguyên Thủy sinh ra Phật Giáo Đại Thừa. Đại Thừa gọi Phật Giáo Nguyên Thủy là Tiểu Thừa. Sau đó Bí Mật Phật Giáo (Mật Giáo) thành lập nên Đại Thừa còn được gọi là Hiển Giáo. Mật Giáo truyền sang Trung Quốc lập ra Mật Tông và sau đó truyền sang Nhật Bản là Chơn Ngôn Tông (Chân Ngôn Tông). Mật Giáo cũng truyền sang Tây Tạng thành ra Kim Cang Thừa. Ngày nay những Tông Thừa nầy tồn tại trong Phật Giáo khắp toàn thế giới. Từ vị Phật có thật trong lịch sử là Thích Ca Mâu Ni Phật, chư Phật và chư Bồ Tát cũng có lịch sử qua kinh điển và triết lý của Tông Thừa Phật Giáo. Bố Cục Phật Giáo Nguyên Thủy Thích Ca Mâu Ni Phật (trang 2) Nhân Gian Phật (Manushi Buddha) (trang 7) Đại Thừa Tam Thế Phật (trang 7) Bồ Tát (trang 11) Quan Tự Tại - Quan Thế Âm (Avalokiteshvara) (trang 18) Tam Thân Phật (trang 28) Báo Thân và Tịnh Độ (trang 33) A Di Đà Phật và Tịnh Độ Tông (trang 35) Bàn Thờ và Danh Hiệu (trang 38) Kim Cang Thừa Tam Thân Phật và Bồ Tát (trang 41) Thiền Na Phật (Dhyana Buddha) (trang 42) A Đề Phật (trang 45) Nhân Gian Phật (Manushi Buddha) (trang 46) Bồ Tát (trang 46) Minh Vương (trang 49) Hộ Pháp (trang 51) Hộ Thần (trang 53) Consort và Yab-Yum (trang 55) Chơn Ngôn Tông và Mật Tông (trang 57) PHẬT GIÁO NGUYÊN THỦY Phật Giáo thành lập và bắt đầu với Thích Ca Mâu Ni Phật. -

Critical Sermons of the Zen Tradition Dr Hisamatsu Shin’Ichi, at Age 87

Critical Sermons of the Zen Tradition Dr Hisamatsu Shin’ichi, at age 87. Photograph taken by the late Professor Hy¯od¯o Sh¯on¯osuke in 1976, at Dr Hisamatsu’s residence in Gifu. Critical Sermons of the Zen Tradition Hisamatsu’s Talks on Linji translated and edited by Christopher Ives and Tokiwa Gishin © Editorial matter and selection © Christopher Ives and Tokiwa Gishin Chapters 1–22 © Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2002 978-0-333-96271-8 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2002 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries.