23 Ahtna Amicus Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alaska Native

To conduct a simple search of the many GENERAL records of Alaska’ Native People in the National Archives Online Catalog use the search term Alaska Native. To search specific areas or villages see indexes and information below. Alaska Native Villages by Name A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Alaska is home to 229 federally recognized Alaska Native Villages located across a wide geographic area, whose records are as diverse as the people themselves. Customs, culture, artwork, and native language often differ dramatically from one community to another. Some are nestled within large communities while others are small and remote. Some are urbanized while others practice subsistence living. Still, there are fundamental relationships that have endured for thousands of years. One approach to understanding links between Alaska Native communities is to group them by language. This helps the student or researcher to locate related communities in a way not possible by other means. It also helps to define geographic areas in the huge expanse that is Alaska. For a map of Alaska Native language areas, see the generalized map of Alaska Native Language Areas produced by the University of Alaska at Fairbanks. Click on a specific language below to see Alaska federally recognized communities identified with each language. Alaska Native Language Groups (click to access associated Alaska Native Villages) Athabascan Eyak Tlingit Aleut Eskimo Haida Tsimshian Communities Ahtna Inupiaq with Mixed Deg Hit’an Nanamiut Language Dena’ina (Tanaina) -

1. Description 1.1 Name of Society, Language, and Language Family: Ahtna, Na Dene, Athapaskan 1.2 ISO Code (3 Letter Code from E

1. Description 1.1 Name of society, language, and language family: Ahtna, Na Dene, Athapaskan 1.2 ISO code (3 letter code from ethnologue.com): ath 1.3 Location (latitude/longitude): 61.312452,-142.470703 1.4 Brief history: Russians first made contact with the Ahtna in 1783. They attempted to set up Copper fort, near Taral, in Ahtna territory, but the Ahtna were hostile towards them, massacring a group of explorers led by Ruff Serebrennikov in 1848, which led to the closing of the fort. When the fort was reopened for a short while, only a little trade between the Ahtna and the Russians occurred. Smallpox killed many Ahtna from 1837-1839. After the US purchased Alaska the Ahtna traded directly with the Alaska Commercial Company at Nuchek and indirectly with other posts in the Yukon. The first major encounter with whites happened at the beginning of the 20th century when word of gold in the area brought masses of people north. This introduced luxuries and tuberculosis to the Ahtna People. By 1930, all Ahtna had been baptized into the Russian Orthodox religion. (De Laguna, Frederica & McClellan, Catherine) 1.5 Influence of missionaries/schools/governments/powerful neighbors: Contact with whites led to epidemics that devastated the Ahtna population. By the mid- 20th century, all Ahtna had been converted or baptized into the Russian Orthodox faith. (De Laguna, Frederica & McClellan, Catherine) 1.6 Ecology The climate of the Copper River valley where the Ahtna lived is transitional between maritime and continental. Snow covered the inhabited area from mid-November through mid-April. -

CURRICULUM VITAE for JAMES KARI September, 2018

1 CURRICULUM VITAE FOR JAMES KARI September, 2018 BIOGRAPHICAL James M. Kari Business address: Dena=inaq= Titaztunt 1089 Bruhn Rd. Fairbanks, AK 99709 E-mail: [email protected] Federal DUNS number: 189991792, Alaska Business License No. 982354 EDUCATION Ph.D., University of New Mexico (Curriculum & Instruction and Linguistics), 1973 Doctoral dissertation: Navajo Verb Prefix Phonology (diss. advisors: Stanley Newman, Bruce Rigsby, Robert Young, Ken Hale; 1976 Garland Press book, regularly used as text on Navajo linguistics at several universities) M.A.T., Reed College (Teaching English), 1969 U. S. Peace Corps, Teacher of English as a Foreign Language, Bafra Lisesi, Bafra, Turkey, 1966-68 B.A., University of California at Los Angeles (English), 1966 Professional certification: general secondary teaching credential (English) in California and Oregon Languages: Field work: Navajo (1970), Dena'ina (1972), Ahtna (1973), Deg Hit=an (Ingalik) (1974), Holikachuk (1975), Babine-Witsu Wit'en (1975), Koyukon (1977), Lower Tanana (1980), Tanacross (1983), Upper Tanana (1985), Middle Tanana (1990) Speaking: Dena’ina, Ahtna, Lower Tanana; some Turkish EMPLOYMENT Research consultant on Dene languages and resource materials, business name Dena’inaq’ Titaztunt, 1997 Professor of Linguistics, Emeritus, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, 1997 Professor of Linguistics, Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, 1993-97 Associate Professor of Linguistics, Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska, 1982-1993 Assistant Professor -

Identity, History and the Athabaskan Potlatch

IDENTITY, HISTORY AND THE NORTHERN ATHABASKAN PO'rLATCH rrr ~ r A thesis Submitted to the Sctlool of Graduate Studies In partial fulfi I ment of the req u i remen ts for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University i c! DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (1990) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (Anthropology) Hamilton, ontario TITLE: Identity, History and the Athabaskan Potlatch AUTHOR: William E.Simeone, B.A. (University of Alaska) M.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Harvey Feit NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 274 ii ABSTRACT A basic theme underlying Athabaskan culture and the potlatch is the duality of competition and cooperation. In the literature on both the Northwest Coast and Athabaskan potlatch this duality is most often considered in one of two ways: as a cultural phenomenon which is functional and ahistorical in nature, or as a product of Native and White contact. In this study I take a less radical view. within Athabaskan culture and the potlatch cooperation and competition exist in a historically reticulate duality which provides the internal dynamic in Northern Athabaskan culture and continues to motivate attempts to redefine the culture and the potlatch. In the context of political and economic domination, however, the duality becomes an opposition in which competition is submerged and reshaped into a symbol for the White man, while cooperation becomes a symbol for unity and Indianness. The resulting ideology, or "Indian way," becomes a critique of the current situation and a vision of things as they should be. The potlatch is the major arena in which this vision derived from the past is reproduced. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Research for this dissertation would have been impossible without financial help from the School of Graduate Studies, McMaster University. -

FY 2021 Final Summary

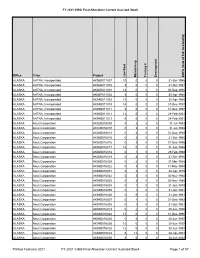

FY 2021 IHBG Final Allocation Current Assisted Stock Office Tribe Project Low RentLow Mutual Help Turnkey II Development (Date DOFA of Full Availability) ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated AK06B011007 10 0 0 0 31-Oct-1986 ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated AK06B011008 3 0 0 0 31-Oct-1987 ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated AK06B011009 14 0 0 0 30-Sep-1990 ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated AK06P011004 8 0 0 0 30-Apr-1980 ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated AK94B011003 12 0 0 0 30-Apr-1980 ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated AK94B011010 14 0 0 0 31-Dec-1997 ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated AK94B011011 6 0 0 0 31-Dec-1997 ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated AK94B011012 12 0 0 0 28-Feb-2001 ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated AK94B011013 6 0 0 0 28-Feb-2001 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK02B016009 0 2 0 0 31-Jul-1983 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK02B016010 0 3 0 0 31-Jul-1986 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK06B016012 0 4 0 0 31-Dec-1985 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK06B016015 0 3 0 0 31-Oct-1985 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK06B016016 0 3 0 0 31-Dec-1985 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK06B016017 14 0 0 0 31-Jan-1986 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK06B016018 0 1 0 0 29-Feb-1988 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK06B016019 0 8 0 0 31-Oct-1990 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK06B016020 0 2 0 0 31-Mar-1988 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK06B016022 0 3 0 0 31-May-1994 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK94B016001 0 2 0 0 30-Apr-1979 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK94B016002 0 3 0 0 30-Nov-1980 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK94B016003 0 2 0 0 30-Nov-1980 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK94B016004 0 1 0 0 31-Jan-1979 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK94B016005 0 1 0 0 31-Oct-1981 ALASKA Aleut Corporation -

Issue 7 | January 2019

Google Site Search Search Home About ELOKA Products Partners News and Events Issue 7 | January 2019 In this issue Indigenous Foods Knowledges Network (IFKN) colleagues visit the Finnish Festival of Northern Fishing Traditions The Indigenous Foods Knowledges Network (IFKN) sent a delegation to Tornio, Finland, to participate in a traditional fishing festival and exchange information about cultural fisheries and food restoration projects with other Indigenous groups from around the world. ELOKA staff contribute to ArcticNet conference ELOKA principle investigator Peter Pulsifer and ELOKA research scientist Noor Johnson both participate in the 14th Annual Scientific Meeting of ArcticNet, held in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. ELOKA collaborates at the Alaska Tribal Conference for Environmental Management ELOKA research scientist Matt Druckenmiller coordinated with Erica Lujan and Donna Hauser of the University of Alaska Fairbanks on a session at one of the largest gatherings of tribal representation in Alaska. Pulsifer discusses Arctic research at Second Arctic Science Ministerial forum ELOKA's Peter Pulsifer was invited to speak at the second Arctic Science Ministerial in Berlin, Germany. Enhancing polar data at the Second Polar Data and Systems Architecture Workshop Researchers and data managers from around the world gathered in Geneva, Switzerland, at the headquarters of the World Meteorological Organization to discuss polar data systems and data sharing. Attu Natural Resource Council receives Nordic Council Environment Prize The Natural Resource Council of Attu, Greenland, is awarded for its forward thinking in establishing a program to document local observations of subsistence marine and terrestrial animals. Sea ice and hunting observations online interface celebrates seven years with ELOKA ELOKA’s ongoing partnership with Alaskan hunters and researchers results in steady improvements to a valuable database of sea ice and hunting observations. -

Ahtna Heritage Dancers Perform at the Quyana Alaska Annual Celebration of Dance

SHERMAN HOGUE / EXPLORE FAIRBANKS EXPLORE / HOGUE SHERMAN AHTNA HERITAGE DANCERS perform at the Quyana Alaska annual celebration of dance. Drum Beat Alaska Natives bring unique energy to performance arts BY ERIC LUCAS MES MISHLER MES A RK J RK A CL or many generations Iñupiaq mothers in at midwinter’s Festival of Native Arts in Fairbanks, thrum- Kaktovik, Alaska, have sung a calming lullaby to ming out a centuries-old song-tale about whale hunting. They might be Athabascan fiddlers whose reels and waltzes their babies that goes, roughly, añaŋa aa añaŋa reflect an art their ancestors adopted from Hudson’s Bay aa añaŋa aa aa aa. Such singing is called qunu, Company agents almost two centuries ago. They might be and it may be thousands of years old. Tlingit village residents showcasing a drum-and-spoken- word allegory about romance between disparate cultures. Allison Warden is an Anchorage-based performance f They might be Alutiiq performers whose guitar-led perfor- artist whose heritage traces back to Kaktovik, on Alaska’s mances meld Russian folk songs and ancient dances North Slope Arctic shore; she fondly remembers her grand- depicting seagull courtship. And they might be members of a modern recording group, Pamyua, performing at the mother singing qunu to her. So Warden has incorporated Anchorage Museum, whose danceable world music blends the line into one of her songs, Ancestor from the Future, an Yup'ik, Inuit, pop and African rhythms. engaging and thought-provoking piece that challenges The ingredients for these types of performances include young people to choose lives with purpose. -

Case Study of Copper Center, Alaska

Technical Report hlumbe~ 7 . .. ... .... .... .. .... ... .... .. .... ..... ... ... ... ..- .. .. ... .. ... .... .... .. .. -. .. .. .. ... ... .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .. ... ... .... .... .. .... ... .. .. .... .. .. .. ... ... .. ... ... .. ... .. ... .. ..-. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. ... ... .. ... ... .-. .. .. .. .. .. ....+... .. -. -. ... ... .. ... .. ..+....... %..%%%%%%..%%%..%..%%-. .. .. ... ... ... .. .. .. ... .. .... ... .... ... .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. ... ... .... .. .... .. ... ... ... ... .... .... ... ... .. ... ... .. .. .. ... .. %%..... ... .. ...%-...%..%%..%%%-...%%%%,.. .. ... .. .. ... ... .. .. .. .... ......... .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. ... .. .. ... .. ... .. .. .. .. .-. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. ..... .. .. .. .,. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... ... .. .. ,. .. .. ... ... ... .. .. .. .... .. .. .. .. .. .. ... ... .... ...+...... ..... ................ ... ..... .... .... .. .... .. .. .. ... .... .. ... ,AJaska ~~s Socioeconomic studies . .Program . %..%%....%%%..%%. ,...%.. .%%-.%. %-........ ... ............ ....... .... .. Sponsor: Bweati of Land ~VlaIWFXWnt . ........ .... Alaska Outer .:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:................ .... .. ... ... ..... ..... .... .... ..... .. ... ... ........ ... .--- ..... .... .. ... .... .. ... .. ... .. ... ... ... ... .-.. .. .... ... .... .%%%..%%%..... .... ... .... ... ... .. .... .... .... .... .. ....... .... .. .. .... .. ..... ......... .... .. .. ..... ... .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. ... .. .. ... .. .. ... .. .... ... .. .. .. .. .. .. ......................................................... -

The Indigenous World 2014

IWGIA THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2014 This yearbook contains a comprehensive update on the cur- rent situation of indigenous peoples and their human rights, THE INDIGENOUS WORLD and provides an overview of the most important developments in international and regional processes during 2013. In 73 articles, indigenous and non-indigenous scholars and activists provide their insight and knowledge to the book with country reports covering most of the indigenous world, and updated information on international and regional processes relating to indigenous peoples. The Indigenous World 2014 is an essential source of informa- tion and indispensable tool for those who need to be informed THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2014 about the most recent issues and developments that have impacted on indigenous peoples worldwide. 2014 INTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS 3 THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2014 Copenhagen 2014 THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2014 Compilation and editing: Cæcilie Mikkelsen Regional editors: Arctic & North America: Kathrin Wessendorf Mexico, Central and South America: Alejandro Parellada Australia and the Pacific: Cæcilie Mikkelsen Asia: Christian Erni and Christina Nilsson The Middle East: Diana Vinding and Cæcilie Mikkelsen Africa: Marianne Wiben Jensen and Geneviève Rose International Processes: Lola García-Alix and Kathrin Wessendorf Cover and typesetting: Jorge Monrás Maps: Jorge Monrás English translation: Elaine Bolton Proof reading: Elaine Bolton Prepress and Print: Eks-Skolens Trykkeri, Copenhagen, Denmark © The authors and The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA), 2014 - All Rights Reserved HURRIDOCS CIP DATA The reproduction and distribution of information contained Title: The Indigenous World 2014 in The Indigenous World is welcome as long as the source Edited by: Cæcilie Mikkelsen is cited. -

Ahtna Knowledge of Long-Term Changes in Salmon Runs in The

Technical Paper No. 324 Ahtna Knowledge of Long-Term Changes in Salmon Runs in the Upper Copper River Drainage, Alaska Final Report for Study 04-553 USFWS Office of Subsistence Management Fishery Information Service Division by William E. Simeone and Erica McCall Valentine, with Siri Tuttle in collaboration with the Mentasta Tribal Council Cheesh’Na Tribal Council Gulkana Tribal Council Tazlina Tribal Council August 2007 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Subsistence Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Divisions of Sport Fish and of Commercial Fisheries: Fishery Manuscripts, Fishery Data Series Reports, Fishery Management Reports, and Special Publications. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Measures (fisheries) centimeter cm Alaska Administrative fork length FL deciliter dL Code AAC mideye-to-fork MEF gram g all commonly accepted mideye-to-tail-fork METF hectare ha abbreviations e.g., Mr., Mrs., standard length SL kilogram kg AM, PM, etc. total length TL kilometer km all commonly accepted liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Ph.D., Mathematics, statistics meter m R.N., etc. all standard mathematical milliliter mL at @ signs, symbols and millimeter mm compass directions: abbreviations east E alternate hypothesis HA Weights and measures (English) north N base of natural logarithm e cubic feet per second ft3/s south S catch per unit effort CPUE foot ft west W coefficient of variation CV gallon gal copyright © common test statistics (F, t, χ2, etc.) inch in corporate suffixes: confidence interval CI mile mi Company Co. -

The Concept of Geolinguistic Conservatism in Na-Dene Prehistory

194 Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska 2010. The Concept of Geolinguistic Conservatism in Na-Dene Prehistory. IN The Dene-Yeniseian Connection, ed. by J. Kari and B. Potter. Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska. New Series, vol 5:194-222. with corrections in 2011 THE CONCEPT OF GEOLINGUISTIC CONSERVATISM IN NA-DENE PREHISTORY James Kari Alaska Native Language Center University of Alaska Fairbanks 1.0. INTRODUCTION1 These papers are the first forum on the implications of the Dene-Yeniseian language stock, and in this article I attempt to engage scholars and intellectuals of varying backgrounds and in several disciplines. I have had the privilege of working with of many of the foremost Alaska Athabascan intellectuals for over 35 years. On many occasions I have heard elders state that Athabascan people have lived in Alaska for more than 10,000 years. Perhaps few of these Athabascan elders would be able to parse the technical articles in this collection, but we are certain that many of their descendents will be among the first readers of these articles. At the February 2008 Dene-Yeniseic Symposium the implications of the geography of the proposed Dene-Yenisiean language stock were one topic of discussion. Johanna Nichols commented that the amount of evidence for Dene-Yeniseian is too large to have the antiquity of more than 10,000 years that is implied for an eastward land-based movement of the Na-Dene branch through Beringia. Nichols added that perhaps unless it can be shown that the Na-Dene and Yeniseian languages have changed at a much slower rate than most languages do. -

Alaska Native Corporation Names and Addresses(Persons Must Also Include Their Shareholder Number Or Other Documentation of Membership)

Alaska Native Corporation Names and Addresses(persons must also include their shareholder number or other documentation of membership) Ahtna, Incorporated Bering Straits Native Corporation PO BOX 649 Anchorage Office Glennallen, Alaska 99588 4600 DeBarr Road, Suite 200 (907) 822-3476 Anchorage, AK 99508-3126 Fax: (907) 822-3495 Ph: 907-563-3788 www.ahtna-inc.com Fax: 907-563-2742 [email protected] The Aleut Corporation 4000 Old Seward Highway, Ste. 300 Bristol Bay Native Corporation Anchorage, Alaska 99503 111 West 16th Avenue, Suite 400 Phone: 907.561.4300 Anchorage, AK 99501 Fax: 907.563.4328 Phone: 907.278.3602 www.aleutcorp.com Toll Free 800.426.3602 www.bbnc.net Arctic Slope Regional Corporation P.O. Box 129 Calista Corporation Barrow, Alaska 99723 Shareholder Services Department Phone: 907-852-8633 301 Calista Court, Suite A Fax: 907-852-5733 Anchorage, Alaska 99518-3028 Toll Free: 800-770-2772 Telephone: (907) 279-5516 www.asrc.com toll-free at 1-800-277-5516 www.calistacorp.com Arctic Slope Regional Corporation Anchorage Office Chugach Alaska Corporation 3900 C Street, Suite 801 3800 Centerpoint Drive, Ste. 700 Anchorage, AK 99503-5963 Anchorage, Alaska 99503 Phone:907-339-6000 Phone: (907) 563-8866 Fax:907-339-6028 Fax: (907) 563-8402 Toll Free: 800-770-2772 www.chugach-ak.com Bering Straits Native Corporation Cook Inlet Region, Incorporated PO Box 1008 3600 San Jeronimo Drive 110 Front Street, Suite 300 Anchorage, Alaska 99508 Nome, AK 99762 Ph: (907) 793-3600 Ph: 907-443-5252 (877) 985-5900 Toll Free Ph: 800-478-5079 www.citci.com