Sustaining Australia's Indigenous Music And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Into the Mainstream Guide to the Moving Image Recordings from the Production of Into the Mainstream by Ned Lander, 1988

Descriptive Level Finding aid LANDER_N001 Collection title Into the Mainstream Guide to the moving image recordings from the production of Into the Mainstream by Ned Lander, 1988 Prepared 2015 by LW and IE, from audition sheets by JW Last updated November 19, 2015 ACCESS Availability of copies Digital viewing copies are available. Further information is available on the 'Ordering Collection Items' web page. Alternatively, contact the Access Unit by email to arrange an appointment to view the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on viewing The collection is open for viewing on the AIATSIS premises. AIATSIS holds viewing copies and production materials. Contact AFI Distribution for copies and usage. Contact Ned Lander and Yothu Yindi for usage of production materials. Ned Lander has donated production materials from this film to AIATSIS as a Cultural Gift under the Taxation Incentives for the Arts Scheme. Restrictions on use The collection may only be copied or published with permission from AIATSIS. SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1988 Extent: 102 videocassettes (Betacam SP) (approximately 35 hrs.) : sd., col. (Moving Image 10 U-Matic tapes (Kodak EB950) (approximately 10 hrs.) : sd, col. components) 6 Betamax tapes (approximately 6 hrs.) : sd, col. 9 VHS tapes (approximately 9 hrs.) : sd, col. Production history Made as a one hour television documentary, 'Into the Mainstream' follows the Aboriginal band Yothu Yindi on its journey across America in 1988 with rock groups Midnight Oil and Graffiti Man (featuring John Trudell). Yothu Yindi is famed for drawing on the song-cycles of its Arnhem Land roots to create a mix of traditional Aboriginal music and rock and roll. -

Af20-Booking-Guide.Pdf

1 SPECIAL EVENT YOU'RE 60th Birthday Concert 6 Fire Gardens 12 WRITERS’ WEEK 77 Adelaide Writers’ Week WELCOME AF OPERA Requiem 8 DANCE Breaking the Waves 24 10 Lyon Opera Ballet 26 Enter Achilles We believe everyone should be able to enjoy the Adelaide Festival. 44 Between Tiny Cities Check out the following discounts and ways to save... PHYSICAL THEATRE 45 Two Crews 54 Black Velvet High Performance Packing Tape 40 CLASSICAL MUSIC THEATRE 16 150 Psalms The Doctor 14 OPEN HOUSE CONCESSION UNDER 30 28 The Sound of History: Beethoven, Cold Blood 22 Napoleon and Revolution A range of initiatives including Pensioner Under 30? Access super Mouthpiece 30 48 Chamber Landscapes: Pay What You Can and 1000 Unemployed discounted tickets to most Cock Cock... Who’s There? 38 Citizen & Composer tickets for those in need MEAA member Festival shows The Iliad – Out Loud 42 See page 85 for more information Aleppo. A Portrait of Absence 46 52 Garrick Ohlsson Dance Nation 60 53 Mahler / Adès STUDENTS FRIENDS GROUPS CONTEMPORARY MUSIC INTERACTIVE Your full time student ID Become a Friend to access Book a group of 6+ 32 Buŋgul Eight 36 unlocks special prices for priority seating and save online and save 15% 61 WOMADelaide most Festival shows 15% on AF tickets 65 The Parov Stelar Band 66 Mad Max meets VISUAL ART The Shaolin Afronauts 150 Psalms Exhibition 21 67 Vince Jones & The Heavy Hitters MYSTERY PACKAGES NEW A Doll's House 62 68 Lisa Gerrard & Paul Grabowsky Monster Theatres - 74 IN 69 Joep Beving If you find it hard to decide what to see during the Festival, 2020 Adelaide Biennial . -

Including Music and the Temporal Arts in Language Documentation. in N

Linda Barwick University of Sydney Barwick, Linda. (2012). Including music and the temporal arts in language documentation. In N. Thieberger (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Fieldwork (pp. 166-179). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Postprint version, with page numbers edited to match the published version. 1 Including music and the temporal arts in language documentation Linda Barwick This chapter is intended for linguistic researchers preparing to undertake fieldwork, probably documenting one of the world’s many small or endangered languages. Recognising that linguists have their own priorities and methodologies in language documentation and description, I will advance reasons for including in your corpus the song and/or instrumental music that you are almost certain to encounter in the course of your fieldwork. I start by providing an overview of current thinking about the nature and significance of human musical capacities and the commonly encountered types, context and significance of music, especially in relation to language. Since research funding usually precludes having a musicologist tag along in the original fieldwork, I will suggest some topics for discussion that would be of interest to musicologists, and make some suggestions for what is needed on a practical level to make your recordings useful to 166 musicologists at a later date. I comment on the technical and practical requirements for a good musical documentation and how these might differ from language documentation, and also provide some suggestions on a workflow for field production of musical recordings for community use. Examples taken from my own fieldwork are intended to provide food for thought, and not to imply that music and dance traditions in other societies are necessarily structured in comparable ways. -

Endangered Songs and Endangered Languages

Endangered Songs and Endangered Languages Allan Marett and Linda Barwick Music department, University of Sydney NSW 2006 Australia [[email protected], [email protected]] Abstract Without immediate action many Indigenous music and dance traditions are in danger of extinction with It is widely reported in Australia and elsewhere that songs are potentially destructive consequences for the fabric of considered by culture bearers to be the “crown jewels” of Indigenous society and culture. endangered cultural heritages whose knowledge systems have hitherto been maintained without the aid of writing. It is precisely these specialised repertoires of our intangible The recording and documenting of the remaining cultural heritage that are most endangered, even in a traditions is a matter of the highest priority both for comparatively healthy language. Only the older members of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. Many of the community tend to have full command of the poetics of our foremost composers and singers have already song, even in cases where the language continues to be spoken passed away leaving little or no record. (Garma by younger people. Taking a number of case studies from Statement on Indigenous Music and Performance Australian repertories of public song (wangga, yawulyu, 2002) lirrga, and junba), we explore some of the characteristics of song language and the need to extend language documentation To close the Garma Symposium, Mandawuy Yunupingu to include musical and other dimensions of song and Witiyana Marika performed, without further performances. Productive engagements between researchers, comment, two djatpangarri songs—"Gapu" (a song performers and communities in documenting songs can lead to about the tide) and "Cora" (a song about an eponymous revitalisation of interest and their renewed circulation in contemporary media and contexts. -

Paul Grabowsky

PAUL GRABOWSKY SELECTED CREDITS DAISY WINTERS (2017) THE MENKOFF METHOD (2015) WORDS AND PICTURES (2013) EMPIRE FALLS (2005) THE JUNGLE BOOK 2(2003) (Original Songs, Lyrics – “Jungle Rhythm”, “W-I-L-D”, “Jungle Rhythm (Mowgli Solo)”) BIOGRAPHY Paul Grabowsky is a pianist, composer, arranger and conductor, and is one of Australia’s most distinguished artists. Born in Papua New Guinea in 1958, Paul was raised in Melbourne where he attended Wesley College. He began classical piano lessons at the age of five, studying with Mack Jost from 1965-1978. He began informal studies in jazz around 1976, and fully devoted his energies to improvised music from 1978. During the 70’s he became prominent in the music scene in Melbourne, working in various jazz, theatre and cabaret projects. He lived in Munich, Germany from 1980-1985, where he was active on the local and European jazz scenes, performing and recording with Johnny Griffin, Chet Baker, Art Farmer, Benny Bailey, Guenther Klatt, Marty Cook and many others. He returned to Australia in 1986. In 1983, he formed the Paul Grabowsky Trio, winner of four ARIA awards and one of Australia’s longest-living and most influential jazz ensembles. He has also won two Helpmann awards, several Bell awards and a Deadly award. He was the Sydney Myer Performing Artist of the year in 2000, and received the Melbourne Prize for Music in 2007. As a performer, he became known for his work with the ‘Wizards of Oz’, a group he co- led with saxophonist Dale Barlow from 1987-1989 and Vince Jones, for whom he was musical director in 1988-89. -

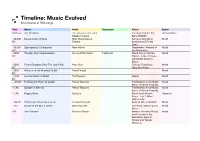

Timeline: Music Evolved the Universe in 500 Songs

Timeline: Music Evolved the universe in 500 songs Year Name Artist Composer Album Genre 13.8 bya The Big Bang The Universe feat. John The Sound of the Big Unclassifiable Gleason Cramer Bang (WMAP) ~40,000 Nyangumarta Singing Male Nyangumarta Songs of Aboriginal World BC Singers Australia and Torres Strait ~40,000 Spontaneous Combustion Mark Atkins Dreamtime - Masters of World BC` the Didgeridoo ~5000 Thunder Drum Improvisation Drums of the World Traditional World Drums: African, World BC Samba, Taiko, Chinese and Middle Eastern Music ~5000 Pearls Dropping Onto The Jade Plate Anna Guo Chinese Traditional World BC Yang-Qin Music ~2800 HAt-a m rw nw tA sxmxt-ib aAt Peter Pringle World BC ~1400 Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal Tim Rayborn Qadim World BC ~128 BC First Delphic Hymn to Apollo Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Epitaph of Seikilos Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Magna Mater Synaulia Music from Ancient Classical Rome - Vol. 1 Wind Instruments ~ 30 AD Chahargan: Daramad-e Avval Arshad Tahmasbi Radif of Mirza Abdollah World ~??? Music for the Buma Dance Baka Pygmies Cameroon: Baka Pygmy World Music 100 The Overseer Solomon Siboni Ballads, Wedding Songs, World and Piyyutim of the Sephardic Jews of Tetuan and Tangier, Morocco Timeline: Music Evolved 2 500 AD Deep Singing Monk With Singing Bowl, Buddhist Monks of Maitri Spiritual Music of Tibet World Cymbals and Ganta Vihar Monastery ~500 AD Marilli (Yeji) Ghanian Traditional Ghana Ancient World Singers -

Theory and Analysis of Melody in Balinese Gamelan

RELATING THE PRESENT TO THE PAST THOUGHTS ON THE STUDY OF MUSICAL CHANGE AND CULTURE CHANGE IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY Bruno Nettl http://www.muspe.unibo.it/period/MA/index/number1/nettl1/ne1.htm The relationship of past to present is one of the principal issues in all human cultures. It is also perhaps the most important task of many areas of scholarship, and in different ways, of musicology and anthropology. In ethnomusicology and in anthropology, one of the principal ways of associating past to present has been through the concepts of culture change and musical change, the idea that something that a society maintains and shares can change in character or in detail and yet remain essentially the same. I would like to approach the relationship of past and present through this concept. It is an immense subject, and you will understand why I have had problems finding ways to grasp it. To deal with it properly might require that one define culture and music and then change, to say nothing of providing a bibliography. But instead, as a more modest goal, I would like to try to circumscribe the subject by mentioning and discussing a few of the issues that dominate this area of endeavor, phrasing each in terms of a widely accepted generalization and then illustrating each with something from my experience. The ultimate concern of musicology has always been the nature of musical change. The majority of musicologists, who see themselves mainly as music historians, have tried to show that there is a systematic way in which music proceeds from past to present, using, for example, the concept of periods, the significance of biography, the belief that similarity or identity must usually be explained by contact and influence. -

Cimf20201520program20lr.Pdf

CONCERT CALENDAR See page 1 Beethoven I 1 pm Friday May 1 Fitters’ Workshop 6 2 Beethoven II 3.30 pm Friday May 1 Fitters’ Workshop 6 3 Bach’s Universe 8 pm Friday May 1 Fitters’ Workshop 16 4 Beethoven III 10 am Saturday May 2 Fitters’ Workshop 7 5 Beethoven IV 2 pm Saturday May 2 Fitters’ Workshop 7 6 Beethoven V 5.30 pm Saturday May 2 Fitters’ Workshop 8 7 Bach on Sunday 11 am Sunday May 3 Fitters’ Workshop 18 8 Beethoven VI 2 pm Sunday May 3 Fitters’ Workshop 9 9 Beethoven VII 5 pm Sunday May 3 Fitters’ Workshop 9 Sounds on Site I: 10 Midday Monday May 4 Turkish Embassy 20 Lamentations for a Soldier 11 Silver-Garburg Piano Duo 6 pm Monday May 4 Fitters’ Workshop 24 Sounds on Site II: 12 Midday Tuesday May 5 Mt Stromlo 26 Space Exploration 13 Russian Masters 6 pm Tuesday May 5 Fitters’ Workshop 28 Sounds on Site III: 14 Midday Wednesday May 6 Shine Dome 30 String Theory 15 Order of the Virtues 6 pm Wednesday May 6 Fitters’ Workshop 32 Sounds on Site IV: Australian National 16 Midday Thursday May 7 34 Forest Music Botanic Gardens 17 Brahms at Twilight 6 pm Thursday May 7 Fitters’ Workshop 36 Sounds on Site V: NLA – Reconciliation 18 Midday Friday May 8 38 From the Letter to the Law Place – High Court Barbara Blackman’s Festival National Gallery: 19 3.30 pm Friday May 8 40 Blessing: Being and Time Fairfax Theatre 20 Movers and Shakers 3 pm Saturday May 9 Fitters’ Workshop 44 21 Double Quartet 8 pm Saturday May 9 Fitters’ Workshop 46 Sebastian the Fox and Canberra Girls’ Grammar 22 11 am Sunday May 10 48 Other Animals Senior School Hall National Gallery: 23 A World of Glass 1 pm Sunday May 10 50 Gandel Hall 24 Festival Closure 7 pm Sunday May 10 Fitters’ Workshop 52 1 Chief Minister’s message Festival President’s Message Welcome to the 21st There is nothing quite like the Canberra International Music sense of anticipation, before Festival: 10 days, 24 concerts the first note is played, for the and some of the finest music delights and surprises that will Canberrans will hear this unfold over the 10 days of the Festival. -

Walakandha Wangga

Walakandha Wang ga Archival recordings by Marett et al. Notes by Marett, Barwick & Ford 1 THE INDIGENOUS MUSIC OF AUSTRALIA CD6 Ambrose Piarlum dancing wangga at a Wadeye circumcision ceremony, 1992. Photograph by Mark Crocombe, reproduced with the permission of Wadeye community. Walakandha Wangga THE INDIGENOUS MUSIC OF AUSTRALIA CD6 Archival recordings by Allan Marett, with supplementary recordings by Michael Enilane, Frances Kofod, William Hoddinott, Lesley Reilly and Mark Crocombe; curated and annotated by Allan Marett and Linda Barwick, with transcriptions and translations by Lysbeth Ford. Dedicated to the late Martin Warrigal Kungiung, Marett’s first wangga teacher Published by Sydney University Press © Recordings by Allan Marett, Michael Enilane, William Hoddinott, Frances Kofod, Lesley Reilly, & Mark Crocombe 2016 © Notes by Allan Marett, Linda Barwick and Lysbeth Ford 2016 © Sydney University Press 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this CD or accompanying booklet may be reproduced or utilised in any way or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without prior written permission from the publisher. Sydney University Press, Fisher Library F03, University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Web: sydney.edu.au/sup ISBN 9781743325292 Custodian statement This music CD and booklet contain traditional knowledge of the Marri Tjavin people from the Daly region of Australia’s Top End. They were created with the consent of the custodians. Dealing with any part of the music CD or the texts of the booklet for any purpose that has not been authorised by the custodians is a serious breach of the customary laws of the Marri Tjavin people, and may also breach the Copyright Act 1968 (Cwlth). -

Bluetongue Australian Guitar Quartets CHARLTON • HOUGHTON KATS-CHERNIN • WESTLAKE Guitar Trek Bluetongue Australian Guitar Quartets

Bluetongue Australian Guitar Quartets CHARLTON • HOUGHTON KATS-CHERNIN • WESTLAKE Guitar Trek Bluetongue Australian Guitar Quartets Nigel WESTLAKE (b. 1958) Six Fish (2003) 15:25 1 I. Guitarfish 2:13 2 II. Sunfish 3:29 3 III. Spangled Emperor 1:16 4 IV. Sling-Jaw Wrasse 1:55 5 V. Leafy Sea Dragon 2:33 6 VI. Flying Fish 3:57 Richard CHARLTON (b. 1955) Five Tails in Cold Blood (Guitar Quartet No. 8) (2017) * 15:02 7 I. Shingleback 3:03 8 II. Lace Monitor 3:17 9 III. Manta Ray Ballet 2:53 0 IV. Water Dragon Dreams 2:57 ! V. Bluetongue 2:44 Phillip HOUGHTON (1954–2017) @ Nocturne (1976) (version for guitar quartet, 2002) 3:19 Opals (1993, rev. 1994) 9:42 # I. Black Opal 2:16 $ II. Water Opal 4:09 % III. White Opal 3:14 8.579060 2 News from Nowhere (1992) 16:39 ^ I. FLUX: Being Lost In Long Grass – TRANCE: Seeing The River 7:57 & II. DRIFT: Slow Boat to Nowhere… Stars on Night Water in the Aqua-Realm 3:02 * III. ROCKS: The Arrival… and the Rocks Hum and Hover 5:40 ( Wave Radiance (2002) (version for guitar quartet, 2004) 6:24 Elena KATS-CHERNIN (b. 1957) ) Bleached Memories (2001) * 10:05 * WORLD PREMIERE RECORDINGS Guitar Trek Timothy Kain, Standard Guitar 1–! #–% (, Treble Guitar @ ^–* ) Minh Le Hoang, Standard Guitar Bradley Kunda, Standard Guitar 7–%, 12 String Guitar 1–6, Treble Guitar (, Baritone Guitar ^–* ) Matt Withers, Standard Guitar #–% (, Bass Guitar 7–@ ^–* ), Dobro 1–6 3 8.579060 Guitar Trek gives special thanks to the late Australian luthier Graham Caldersmith OAM for his original conception and design of the Guitar Family. -

Semester 2 – 2014

The SEMESTER 2 2014 Marrma’ Rom Two Worlds Foundation Congratulations to Dion and Jerol Wunungmurra Semester Two 2014 was highlighted by the fantastic achievement of two of our students graduating from Year 12. Dion and Jerol have been part of the Foundation since 2012 and we are very proud of them and what they have accomplished during the last 3 years. We are also very proud of them for deciding to return to Geelong next year and continue their endeavors to become Aboriginal Health Workers. [ Below is a short article by Jerol about the St. Joseph’s College Graduation Mass, for which Dions and Jerols’ parents flew down to attend: On the 19th of October 2014, the second week of school in Term 4, Dion’s parents and my dad came down to Geelong. They drove to Gove from Gapuwiyak and stayed in town. The next day they went to Gove airport and they flew from Gove to Cairns and 2 hours later they flew to Melbourne. Dion and I woke up early morning and Cam drove us to Gull bus. We checked in then the bus driver drove us to Tullamarine. We only waited for about 5 minutes then we saw them arrive. We caught the Skybus to Southern Cross and waited for the others in the city. We were performing at the Melbourne Festival that day. After the festival finished we caught a train back to Geelong. Dad was staying with me and Dion and his mum and dad were staying at Narana Cultural Centre. On Monday we went to St. -

Sydney Conservatorium of Music Postgraduate Handbook

2008 Postgraduate handbook Sydney Conservatorium of Music Postgraduate handbook Set a course for Handbooks online … visit www.usyd.edu.au/handbooks Acknowledgements Acknowledgements The Arms of the University Sidere mens eadem mutato Though the constellation may change the spirit remains the same Copyright Disclaimers This work is copyright. No material anywhere in this work may be 1. The material in this handbook may contain references to persons copied, reproduced or further disseminated ± unless for private use who are deceased. or study ± without the express and written permission of the legal 2. The information in this handbook was as accurate as possible at holder of that copyright. The information in this handbook is not to be the time of printing. The University reserves the right to make used for commercial purposes. changes to the information in this handbook, including prerequisites for units of study, as appropriate. Students should Official course information check with faculties for current, detailed information regarding Faculty handbooks and their respective online updates along with the units of study. University of Sydney Calendar form the official legal source of Price information relating to study at the University of Sydney. Please refer to the following websites: The price of this handbook can be found on the back cover and is in www.usyd.edu.au/handbooks Australian dollars. The price includes GST. www.usyd.edu.au/calendar Handbook purchases Amendments You can purchase handbooks at the Student Centre, or online at