Page 1 a Pile of Aircraft Parts Outside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter 07-6

VOL XXIX #2 1 July 2007 I n t e r n a t i o n a l F l e e t C l u b N E W S L E T T E R Editor / Publisher From the Editor mailing well over 400 hard copies Jim Catalano world wide. Last issue we sent out over 200 requests for updated info to 8 Westlin Lane Wildly optimistic, I started the open those we hadn’t heard from since Cornwall NY 12518 cockpit season off on April 1 with two 1999 – and received only about 10 great flights in 60-degreee weather, responses. We have no idea whether E-Mail clear skies – then it dropped to 35 these 200 folks are receiving the [email protected] degrees and snowed on and off for 2 newsletter, or are enjoying it or weeks. I thought for about a minute couldn’t care less – but it’s almost like Telephone about putting on the old MacKenzie throwing leaflets overboard on a fly-by 845 - 534 - 3947 Airservice wooden skis, then thought and not knowing what impact we’re better of it. having. Fleet Web Site Ninety de- web.mac.com/fleetclub grees here If you’re one of this today, great Silent Half, we would for warming Fleet Net love to hear from you. up 2 gallons Don’t just sit there on groups.yahoo.com/ of oil, short- your er …ah… seat group/fleetnet ening up my pack, send news, pre-flight by several minutes so I can send photos and con- Cover Photo quickly get up in the sky and go no- sider sending a dona- Mike O’Neil’s 1930 where fast in 615S! tion of at least $10 a Model 7 Fleet - N756V year to keep us ahead Club membership now hovers around of the financial power Designer 450 strong; 5% receive the newsletter curve. -

MODEL BUILDER MAY 1980 FULL SIZE PLANS AVAILABLE - SEE PAGE 108 15 Least 20 Grains Per Inch

MO BUI volume 10, number 100 ISSN 0194 7079 • CURTISS F6C-1 Eugene Martin's 2 " R/C Scale Classic • GOLDEN EAGLE New Std. Class Sailplane by Tom Williams • SKYROCKET - 1940 O.T. By Larry Eisinger • F.A.C. TRAINER F/F Sport Rubber by Frank Scott The i h Radio co of Whttt makes the Ι -series so unique' Full programming. Modular AM and FM queue) boards. ATV. Direct Servo Con trol. Dual rates dnd mixing circuitry. Human engineered controls of uncommon quality and precision. And the meticulous hand rails mans hip that has made us famous. Tl»c acutpenbe U N 2ft p ^risciti^ l»uwt*tii 4. 5. 6 and S channel models, plus the 5JH/h Inside and out the Futaba "Supcmtlios helicopter and the are built for !he most critical radio control 6JB/be.<; version* enthusiasts sc»s«>».· And now the . the reliability, and technical wizardry/ "“« j new S124 servo, with to match the most demanding and skillful pat dual ball bearings and tern flyers!' noted Mode! AirpUmt .Virus. coreless high torque/high speed motor, is Fixing Models found the component available as a J-series option. assembly and circuit board layout "truly Closely examine the J-senes at your RC excellent" specialist. Isn't your model worthy of a Futaba? Futaba / ulaba t orporatioa of A mtrica 555 Hr« tVi m naStrrtt/C<>mpcim/CA <*>220 L B A T T (% CHECK ö -® THINK TWICE m I B The best Glow Plug and the best Fuel go together like a horse and carriage. You can’t get the best out of either without the other. -

VA Vol 6 No 5 May 1978

mittee (or committees) on which you would like to serve and drop a note to the chairman volunteering your services. He' ll be most happy to hear from you , and you will find that you will really enjoy being a " member of the team". If you can't plan far enough in advance to be sure that you are going to be able to attend the convention this year, there will still be plenty of opportunities for you to volunteer your services when you arrive. A Divi sion convention manpower committee under the chair THE RESTORER'S CORNER manship of Vice-President Jack Winthrop will be in operation at the Antique/Classic Division convention By J. R. Nielander, Jr. headquarters barn. This is the little red barn with the yellow windsock located about a half mile south of the airport control tower. Drop by the barn and let Jack, or one of his committeemen, sign you up to serve on the committee of your choice. The manpower com mittee will be happy to help you make that choice if you are undecided, and they will be able to assist you in scheduling your volunteer periods so that there will be CONVENTION MANPOWER (AND WOMANPOWER) no conflict with any forums, workshops, etc., which of the convention. Your Division headquarters barn you might want to attend. Your officers and chairmen Convention planning becomes a very real and time requires four volunteers operating four three-hour look forward to the pleasure of meeting you and work comsuming part of the lives of all of your Division shifts per day, or a total of 128 shifts during the ing with you . -

AIR FORCE RENAISSANCE? Canada Signals a Renewed Commitment to Military Funding THINK CRITICAL MISSIONS

an MHM PUBLisHinG MaGaZine 2017 edition Canada’s air ForCe review BroUGHt to yoU By www.skiesMaG.CoM [INSIDE] RCAF NEWS YEAR IN REVIEW RETURN TO THE “BIG 2” BAGOTVILLE’S 75TH FLYING RED AIR VINTAGE WINGS RESET AIR FORCE RENAISSANCE? CANADA SIGNALS A RENEWED COMMITMENT TO MILITARY FUNDING THINK CRITICAL MISSIONS Equipped with cutting edge technology, all weather capability and unrivaled precision and stability in the harshest environments. Armed with the greatest endurance, longest range and highest cruise speed in its class. With maximum performance and the highest levels of quality, safety and availability to ensure success for demanding search and rescue operations - anywhere, anytime. H175 - Deploy the best. Important to you. Essential to us. RCAF Today 2017 1 Mike Reyno Photo 32 A RENAISSANCE FOR THE RCAF? The Royal Canadian Air Force appears to be headed for a period of significant renewal, with recent developments seeming to signal a restored commitment to military funding. By Martin Shadwick 2 RCAF Today 2017 2017 Edition | Volume 8 42 IN THIS ISSUE 62 20 2016: MOMENTS AND 68 SETTING HIGH STANDARDS MILESTONES The many important “behind the scenes” elements of the Canadian Forces The RCAF met its operational Snowbirds include a small group of 431 commitments and completed a number Squadron pilots known as the Ops/ of important functions, appearances and Standards Cell and the Tutor SET. historical milestones in 2016. Here, we revisit just a few of the year’s happenings. By Mike Luedey 30 MEET THE CHIEF 72 PLANES AND PASSION RCAF Chief Warrant Officer Gérard Gatineau’s Vintage Wings is soaring Poitras discusses his long and satisfying to new heights, powered by one of its journey to the upper ranks of the greatest assets—the humble volunteer. -

IPMS Canada RT

IPMS Canada RT (Random Thoughts) Index Maintained by: Fred Hutcheson C5659 List by Category and Subject snail: Box 626, Station B, Ottawa, ON K1P 5P7 e-mail: [email protected] Saturday, April 2, 2016 web: www.ipmscanada.com Page 1 of 51 IPMS Canada - RT Index - List by Category and Subject Volume Subject Designation Country Comments Category: aircraft 1603 184 Shorts Type 184r UK Airframe vf kit @1:72 3104 40B Boeing40B-4a USA build CMR 1:72 resin kit 0028 504 Avro 504a UK Cdn mkgs (Golden Centennaires) 0412 504 Avro 504a UK Nightfighter mkgs 0606 504 Avro 504Ka UK Swedish mkgs - 1919 0606 504 Avro504a UK Cdn mkgs, 1920-28 0611 504 Avro 504Ka UK Civil mkgs - 1918 0905 504 Avro 504a UK 0906 504 Avro 504a UK 0909 552 Avro 552a UK 2305 707 Boeing707r Canada Leading Edge decals & refuel pod 1:72 0809 707/720 Boeing 720a USA Civil mkgs 0202 707/C-135 Boeing C-135a USA Civil Federal Aviation Adm mkgs 2306 707/C-135 Boeing KC-135r USA Detail & Scale book 2603 707/E-3 Boeing E-3 Sentrya USA building Airfix kit @1/72 0612 727 Boeing727a USA Cdn civil mkgs 0612 737 Boeing737a USA Cdn civil mkgs 0711 737 Boeing T-43a USA USAF trainer mkgs 1504 737 Boeing 737r USA Maquettes M&B kit @1:100 2303 737 Boeing 737-300a USA markings for several airliners 2706 737 Boeing 737-200r USA JBOT decals for ZIP Air @ 1:200 1704 747 Boeing 747r USA book on history & photos of the type 0210 A 143 Amiot143a France Int dwg 1901 A-1 Morane A-1a France Formaplane vacuform 0702 A-2 Spad A-2a UK Conv Spad S 7 to A 2 0704 A-7 Anotov A-7a USSR Detail dwgs, 2002 Access -

The Nanton Lancaster Society Newsletter

THE NANTON LANCASTER SOCIETY NEWSLETTER BOMBER Command MUSEUM of Canada VOLUME 24 ISSUE 2 FALL/WINTER 2010 Page 5 Page 4 Page 8 Page 13 Page 18 Page 19 2 BOARD OF DIRECTORS PRESIDENT‘S REPORT Rob Pedersen ………………….. Charlie Cobb Rob Pedersen Greg Morrison ………………… Brian Taylor As I sit down to write this note, with Brent Armstrong ……………. Barry Beresford Remembrance Day just around the corner, I Dan Fox ……….……………... Tink Robinson am once again reminded of just how big a Bob Evans ……... …………... Karl Kjarsgaard sacrifice was made so that we may live in a ……………….. John Phillips ……………... ————–—Volunteer positions———–—- country free of oppression. It is with a Honourary President ……. …….. Don Hudson particular fondness and sadness that I President …………………. ……. Rob Pedersen remember those individuals who left their Vice-President …………. ……. Greg Morrison homeland but did not return. Secretary …………………. ……. Charlie Cobb Continuing to tell the story of those who Treasurer ………………………. Brian Taylor served in Bomber Command kept the Curator - Editor ……………………. Bob Evans volunteers at your museum very busy this Anson Restoration …….………. Rob Pedersen past five months. With multiple events held Gift Shop coordinator…………. Ev Murakami each month it was a very busy summer Library & Displays …………….. Dave Birrell indeed. From monthly engine runs to Webmaster …………………. Brent Armstrong special events, from traveling displays to —-——————— STAFF————————— Office Manager ……………………. Julie Taylor hosting movie crews, at the museum, there Visitor Services Manager…………..Bev Nelson was never a lack of things to see or do. Next year promises to be just as busy as NEWSLETTER CONTENTS this year. Five engine run dates have been set and will be posted on our website Executive list - President’s Report ………. -

The Winnsock

The Winnsock Read about the Vintage Wings inside Winnipeg Area Chapter of RAA Canada October 2011 Executive Directors President: Jim Oke: – 344-5396 Harry Hill - 888-3518 Past President: Ben Toenders – 895-8779 Bert Elam – 955-2448 Memberships: Steven Sadler – 736-3138 Ken Podaima – 257-1275 Secretary: still looking for a volunteer Jill Oakes - 261-1007 Treasurer: Don Hutchison – 895-1005 Gilbert Bourrier – 254-1912 Bob Stewart – 853-7776 NEWSLETTER: Bob Stewart Box 22 GRP 2 RR#1 Dugald, MB R0E 0K0 Phone: 853-7776 Email: [email protected] CALENDAR OF EVENTS October 20, 2010 AGM, Elections, Arro and First Flight Awards Nov. 19, 2010 Tour planned to Wahpeton Airport, Wahpeton North Dakota Dec 10, 2010 Christmas potluck January 2011 Rust Remover – date and location to be finalized Page 1 of 8 The Winnsock Election of Officers and Directors – October 20th We’re always looking for Officers and Directors to bring energy and new ideas to the Executive. If you are interested in serving on the Executive or have someone you’d like to nominate, please contact Jim Oke at 344-5396. Elections will be held at our regular meeting on October 20th. Also at our October meeting Raymond Firer will give a presentation on, "My time with the South Africa Air Force (SAAF)" How does someone from Winnipeg get interested in joining the South African Air Force?! Raymond Firer's presentation will cover what interested him about aviation, how he got into the South African Air Force, and the training programs he experienced. In addition he will share the oddities, near misses and camaraderie - the joys and frustrations of flying in South Africa! Everyone welcome. -

Techtalk: Fleet Finch and Canuck

BRINGING BRITISH COLUMBIA’S AVIATION PAST INTO THE FUTURE CCAANNAADDIIAANN MMUUSSEEUUMM OOFF FFLLIIGGHHTT TTEECCHHTTAALLKK:: FFLLEEEETT FFIINNCCHH AANNDD CCAANNUUCCKK The Canadian Museum of Flight is presenting a series of informal technical talks on aircraft in its fleet. These talks will cover topics ranging from the history of the com - pany; the history of the aircraft type; and its development; production methods and places; the history of the engine and its development. Also covered will be the challenges in maintaining and flying these classic aircraft in today’s environment; how the mechanics find the parts and how the pilots keep current on flying a 70 year old flying machine designed before the dawn of the jet age. This will be followed by details of how the aircraft is prepared for flight; how the en - gine is started; followed by an engine start and flight. During the proceedings, a draw will be conducted entitling the lucky winner to a flight in the aircraft being discussed (some conditions apply). FLEET 16B FINCH FLEET 80 CANUCK 2 THE HISTORY OF THE FLEET FAMILY OF AIRCRAFT CORPORATE HISTORY Reuben Fleet was born on March 6, 1887, in Montesano, Washington. The Fleets were a prosperous family; his fa - ther was city engineer and county auditor for Montesano, and owned large tracts of land in the Washington Territory. Reuben grew up in Grays Harbor, Washington. At 15, Fleet attended Culver Military Academy where his uncle was su - perintendent. In 1907, Fleet returned home where he began teaching all grades from first through eighth. After a num - ber of months, Fleet set himself up as a realtor and resigned from teaching. -

RCAF Aircraft Types

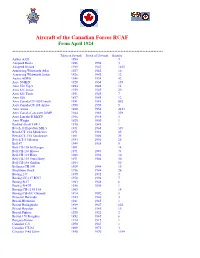

Aircraft of the Canadian Forces RCAF From April 1924 ************************************************************************************************ Taken on Strength Struck off Strength Quantity Airbus A320 1996 5 Airspeed Horsa 1948 1959 3 Airspeed Oxford 1939 1947 1425 Armstrong Whitworth Atlas 1927 1942 16 Armstrong Whitworth Siskin 1926 1942 12 Auster AOP/6 1948 1958 42 Avro 504K/N 1920 1934 155 Avro 552 Viper 1924 1928 14 Avro 611 Avian 1929 1945 29 Avro 621 Tutor 1931 1945 7 Avro 626 1937 1945 12 Avro Canada CF-100 Canuck 1951 1981 692 Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow 1958 1959 5 Avro Anson 1940 1954 4413 Avro Canada Lancaster X/MP 1944 1965 229 Avro Lincoln B MkXV 1946 1948 3 Avro Wright 1925 1930 1 Barkley-Grow T8P-1 1939 1941 1 Beech 18 Expeditor MK 3 1941 1968 394 Beech CT-13A Musketeer 1971 1981 25 Beech CT-13A Sundowner 1981 1994 25 Beech T-34 Mentor 1954 1956 25 Bell 47 1948 1965 9 Bell CH-139 Jet Ranger 1981 14 Bell CH-136 Kiowa 1971 1994 74 Bell CH-118 Huey 1968 1994 10 Bell CH-135 Twin Huey 1971 1994 50 Bell CH-146 Griffon 1994 99 Bellanca CH-300 1929 1944 13 Blackburn Shark 1936 1944 26 Boeing 247 1940 1942 8 Boeing CC-137 B707 1970 1994 7 Boeing B-17 1943 1946 6 Boeing B-47B 1956 1959 1 Boeing CH-113/113A 1963 18 Boeing CH-47C Chinook 1974 1992 8 Brewster Bermuda 1943 1946 3 Bristol Blenheim 1941 1945 1 Bristol Bolingbroke 1939 1947 626 Bristol Beaufort 1941 1945 15 Bristol Fighter 1920 1922 2 Bristol 170 Freighter 1952 1967 6 Burguss-Dunne 1914 1915 1 Canadair C-5 1950 1967 1 Canadair CX-84 1969 1971 3 Canadair F-86 Sabre -

Unicorn 122.35

What to Monitor? cussion about some rather severe technical So off you go to your local airshow, scan- problems with a European jet fighter at one air ners in your backpack, fresh batteries in a side show last year. The problems were resolved pocket and a good pair of headphones. Now, minutes before its performance, but left me what should you listen to? Tip number one; turn wondering whether it was safe to remain in the on your scanner on the way to the air show and area while the plane was performing. scan the aviation band. Even before the show And, of course, you will remember the fea- starts aircraft will be arriving and talking to the ture article in last month's MT about the Snow- local control center and tower controllers. In birds. The Snowbirds leader cockpit to cockpit fact, if you live near to where the air show is commands can be heard on 272.1 MHz -a fre- going to take place. it is even worth monitor- quency that many low- priced scanners cannot ing the aviation band (108 -136 MHz) for a day receive. So, if you want to monitor the Snow- or two before the event to listen out for early birds, make sure you get a scanner that covers arrivals. Air show exhibits are often mustered the military aviation band. The Snowbirds corn- at a local airfield during the days before the mand frequency is sometimes relayed over the event - especially if they are going to be a part public address system at major air shows, but of the ground display. -

The Plan in Maturity 279 RCAF. a Fabric-Covered Biplane, with Two

The Plan in Maturity 279 RCAF. A fabric-covered biplane, with two open cockpits in tandem, it was powered by a radial air-cooled engine and had a maximum speed of I I 3 mph. He found it 'a nice, kind, little aeroplane,' though the primitive Gosport equipment used to give dual instruction in the air was 'an absolutely terrible system. It was practically a tube, a flexible tube' through which the instructor talked 'into your ears . like listening at the end of a hose. ' MacKenzie went solo after ten hours. His first solo landing was complicated. As he approached, other aircraft were taking off in front of him, forcing him to go around three times. 'I'll never get this thing on the ground, ' he thought. His feelings changed once he was down. 'It was fantastic. Full of elation.' Although they were given specific manoeuvres to fly while in the air, '99% of us went up and did aerobatics . .. instead of practising the set sequences. ' Low flying was especially exciting, 'down, kicking the tree tops, flying around just like a high speed car. ' The only disconcerting part of the course was watching a fellow pupil 'wash out. ' 'You would come back in the barracks and see some kid packing his bags, ' he remembered. 'There were no farewell parties. You packed your bags and . snuck off . It was a slight and very sad affair. ' Elementary training was followed by service instruction as either a single- or dual-engine pilot. There was no 'special fighter pilot clique' among the pupils, but MacKenzie had always wanted to fly fighters and asked for single-engine training. -

Beavertales 05 2019

May 2019 Edition A couple members have had problems with their PayPal payment when attempting to renew their membership. We’ve tracked the prob- lem down, and it turns out that they sent payment to the [email protected] address. While that is IPMS Canada’s email address, it’s not the one registered with PayPal. So if you are renewing your Yes, your last issue of RT was very late reaching membership, please just go to the website – www. you. What was supposed to have taken 10 days or ipmscanada.com – and use the buttons on the JOIN/ so to print and ship to us dragged out to well over RENEW page, and everything will work just fine. a month! We’ll put this one down to the storms and flooding that were ravaging southern Ontario. Then our printer had a major equipment breakdown. Fi- nally, as if that weren’t enough, there were problems getting out PayPal account payment system to mesh If you’re going to the US Nats, this with the new website software, and we couldn’t send man wants to see you! RT editor, out any renewal notices until that was fixed! Every- Steve Sauvé, will be organizing the thing now seems to be working OK, and hopefully judging for the IPMS Canada “Best we can get back on track. Sorry for all the fuss and Canadian Subject” award, and would inconvenience. like you to help with the selection. So when you see him – he’ll probably be in mufti, wearing an IPMS Canada ANY IDEAS? shirt – say hello and tell him you’d like to help.