Carney, Margaret 03-08-1986 Transrcipt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Razorcake Issue #27 As A

t’s never been easy. On average, I put sixty to seventy hours a Yesterday, some of us had helped our friend Chris move, and before we week into Razorcake. Basically, our crew does something that’s moved his stereo, we played the Rhythm Chicken’s new 7”. In the paus- IInot supposed to happen. Our budget is tiny. We operate out of a es between furious Chicken overtures, a guy yelled, “Hooray!” We had small apartment with half of the front room and a bedroom converted adopted our battle call. into a full-time office. We all work our asses off. In the past ten years, That evening, a couple bottles of whiskey later, after great sets by I’ve learned how to fix computers, how to set up networks, how to trou- Giant Haystacks and the Abi Yoyos, after one of our crew projectile bleshoot software. Not because I want to, but because we don’t have the vomited with deft precision and another crewmember suffered a poten- money to hire anybody to do it for us. The stinky underbelly of DIY is tially broken collarbone, This Is My Fist! took to the six-inch stage at finding out that you’ve got to master mundane and difficult things when The Poison Apple in L.A. We yelled and danced so much that stiff peo- you least want to. ple with sourpusses on their faces slunk to the back. We incited under- Co-founder Sean Carswell and I went on a weeklong tour with our aged hipster dancing. -

The Providence Phoenix | February 22, 2013 3

february 22–28, 2013 | rhode island’s largest weekly | free VOTE NOW! support your favorites at thephoenix. com/best THE NEW ABOLITIONISTS Why the climate-justice movement must embrace its radical side _by Wen Stephenson | p 6 tHis drum circles and porn beer on a budget Just in A weekend at the RI Men’s Gathering | p6 !Warming up to ‘craft lite’ | p10 North Bowl has been nominated by The Phoenix readers for: BEST PLACE TO BOWL Please vote for us! SCAN HERE Or vote online: thephoenix.com/BEST 71 E Washington St North Attleboro, MA 02760 508.695.BOWL providence.thephoenix.com | the providence phoenix | February 22, 2013 3 february 22, 2013 Contents on the cover F PHOTO-ILLUSTRATION By jANET SMITH TAyLOR IN THIS ISSUE p 6 p 10 p 24 6 the new abolitionists _wen stephenson For the second time in American history, a generation has to choose between an entrenched system of industrial profit — and saving millions of human lives. 14 homegrown product _by chris conti All killer, no filler: theo martins offers a guided tour of Wonderland. 15 art _by chris conti Serious comics: “story/line: narrative form in six graphic novelists” at RIC. 16 theater _by bill rodriguez Mind games: Epic Theatre Company’s six degrees of separation. 24 film _by peter keough If Argo doesn’t win the Oscar for Best Picture, it means the terrorists have won. Plus, a “Short Take” on identity thief. IN EVERY ISSUE 46 phillipe & Jorge’s cool, cool world Ronzo gets the boot | Public enemy #1 | Who’s right, who’s wrong? | 6 Seekonk rocks 4 the city _by derf 7 5 this Just in In the woods with the Rhode Island 10 Men’s Gathering | WPRO cans Ron St. -

The District of Columbia Housing Authority + + + + + Board of Commissioners Meeting + + + + + Wednesday March 13, 2019 + + +

1 THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA HOUSING AUTHORITY + + + + + BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS MEETING + + + + + WEDNESDAY MARCH 13, 2019 + + + + + The Board of Commissioners met in the 2nd Floor Board Room, 1133 North Capitol Street, N.E., Washington, D.C., at 1:00 p.m., Neil Albert, Chairman, presiding. COMMISSIONERS PRESENT: NEIL ALBERT, Chairman WILLIAM SLOVER, Vice Chairman KENNETH D. COUNCIL, Commissioner NAKEISHA NEAL JONES, Commissioner JOSE ARNALDO ORTIZ GAUD, Commissioner FRANSELENE ST. JEAN, Commissioner LEJUAN STRICKLAND, Commissioner ANTONIO TALIAFERRO, Commissioner AQUARIUS VANN-GHASRI, Commissioner STAFF PRESENT: TYRONE GARRETT, Executive Director ALETHEA MCNAIR, Manager of Board Relations COMMISSIONERS ABSENT: BRIAN KENNER, Commissioner KEN GROSSINGER, Commissioner NEAL R. GROSS COURT REPORTERS AND TRANSCRIBERS 1323 RHODE ISLAND AVE., N.W. (202) 234-4433 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20005-3701 www.nealrgross.com 2 CONTENTS Call to Order ................................. 3 Moment of Silence and Quorum Approval of Minutes ........................... 5 February 13, 2019 Executive Director's Report ................... 8 RESOLUTION 19-06 To Approve the Allocation of up to Eight (8) Project Based Vouchers to Capper Square 769N and Authorize the Execution of Other Related Documents for Capper Square 769N ............. 32 RESOLUTION 19-07 To Authorize the Execution of Contracts for Vacant Unit Repair/Make Ready Services ....... 53 RESOLUTION 19-08 To Approve the Use of Local Subsidies to Support the Creation of Affordable Housing in the District of Columbia for the Providence Place New Communities Initiative Project ...................................... 68 Public Comment ............................... 86 Adjourn ..................................... 128 NEAL R. GROSS COURT REPORTERS AND TRANSCRIBERS 1323 RHODE ISLAND AVE., N.W. (202) 234-4433 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20005-3701 www.nealrgross.com 3 1 P-R-O-C-E-E-D-I-N-G-S 2 (1:07 p.m.) 3 CHAIRMAN ALBERT: My name is Neil 4 Albert. -

Parliamentand Broadcasting. by IAN FRASER

Radia Times,December 51; 1920 A MESSAGE FROM THE EARL OF CLARENDON. Eouthern Ech ret snE neniens (etal Aras he ee AE five RPO Ia UMELAY Lae Puanceeste aerate * a rita fr taee auN i : : tg,Eh ma i ine : waley my ry =i sie AL The journal of the British Broadcasting Corporation, = Wik ee aa ee gle & Vol. 14. No. 170, [,.332t5.... DECEMBER 31, 1926. ~ Every Friday. Two Pence. - Parliamentand Broadcasting. By IAN FRASER. [Captain Ion Fraser, WP, is chairman of St. measure with their manifold duties, and have and always have been matters upon which Dunston's, and wae a member of Lord Crawford's unfortunately little time to investigate by it is not merely reasonable, but desirable, that Committers on Broadcasting.. In the following their own research everyone of the multi- Members of Parliament should inform them- article he seeks for (he reasons why Parliament tude of public questions that come before selves; * fags so far behind the pudlia in taking an interest them. They must give a preference to those It is noticeable how few of the important tm al thal has (a do with broadcasting. | subjects which insist upon-their attention newspapers devoted much space to the prob- because of the interest which they arouse in lem in its wider aspect before and after the HY does Parliament take so little their constituencies. Parliamentary debate. Even amongst the interest in broadcasting ? It may But why does not the future of broad- more serious papers, with two or three notable be that an attempt to. answer this casting intrude itself upon their attention exceptions, there was a curious absence of question will help listeners to gam a correct in such a way that study of its progress thoughtful suggestions or reasoned writing. -

Tctiens Supplied by ELM Are the Beet That Can Be Made From-The Orig Nal Document

Odell-Fisher so, al Seneing the. Seta A' CUrriculUequid Education for Oradea ImO and -Three Virginia Inst.' OfMarine SolatiCev,G Va. SPONS AGENCY National. Oceanic it (DOC) I. Rockville 70 57p Marine Education Science. Gloucas .EDRS ORTOE MF-$0.133 NC-$3.50 Plus Postaged DESCRIPTORS *Biology Elementary Education; -*Elementary School Science; *Environmental Education; *Marine -Biolo4y,' *oceanology; Primary Education; *Science, Activities; Science education;, ,Zoology ARSTRACT Thin curricillum guide in ma ine education for 'grades two and three. It gives information_ _ for tle _ and_ maintenance of .marine aquariums, as well as information on Ihecare and feeding of marine animals. The unit should take' about threeor four weeks, A calendar is given shoving- the amount of,time needed, for each Part.-The guide isdivinedinto seven parts.sntitled: 11) Setting On:-(2)Observing Marine Amiials; (3) Inferring About Marine Animals; :14) classifying Beings In ThingS;- 45) Inferring' AbOut parts:, of Living Things; (6)Problem Solving; and A1) Evaluatior. Each section _contains tic) to fourstudent activities. A list of related .books and films are also given fot each section. .(13E). *** ** ************ *** ********* tctiens supplied by ELM are the beet that can be made from-the orig nal document. *** ****** ******** **** ************* ** ** OpARTMIINT OP HeaLLTH, leUEATION A WELFAmil NATIONAL INSTlyuTe 00 jpUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO. DuEE biEXAC TL y AS wrciweD FRb.( THE PERSON ON ORGANIZATION ORIGIN. ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR ()PINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY PEROE. SENT DEE,IctAk NATIONAL INSTITUTE CIF EDUCATION posur:IoN ON POLIO' "PUIIN11::51(IN 10 III 1,1101JU1.L MAILIHAL I4AOLEN otnN 1CU LIY 10 iiDLICA'l Hirs.LAt.lir .Joinirs-9 min HOW CIA-1111 AND wo2 (PAHL; (J, tilL F.111C 5YL,TrM" three ht. -

Surprised by Hope

Digital Download Full Book SURPRISED BY HOPE 0031032470x_SurprisedHope_pg_int_CS4.indd31032470x_SurprisedHope_pg_int_CS4.indd 1 111/30/091/30/09 99:25:25 AAMM 0031032470x_SurprisedHope_pg_int_CS4.indd31032470x_SurprisedHope_pg_int_CS4.indd 2 111/30/091/30/09 99:25:25 AAMM Participant’s Guide SURPRISED BY HOPE Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection, and the Mission of the Church Six Sessions N. T. WRIGHT with Kevin and Sherry Harney 0031032470x_SurprisedHope_pg_int_CS4.indd31032470x_SurprisedHope_pg_int_CS4.indd 3 111/30/091/30/09 99:25:25 AAMM ZONDERVAN Surprised by Hope Participant’s Guide Copyright © 2010 by N. T. Wright Requests for information should be addressed to: Zondervan, Grand Rapids, Michigan 49530 ISBN 978-0-310-78469-2 (Full text; group use download) All Scripture quotations are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide. Any Internet addresses (websites, blogs, etc.) and telephone numbers printed in this book are offered as a resource. They are not intended in any way to be or imply an endorsement by Zondervan, nor does Zondervan vouch for the content of these sites and numbers for the life of this book. All rights reserved. The original purchaser of this product shall have the right to make copies for their group, provided such copies are not resold or distributed to the general public. Otherwise, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means — electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other — except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

Standards and Originals - a Library Suggestion by Massimo Ciolli "Mc2"

standards and originals - a library suggestion by massimo ciolli "mc2" musicista album (I LOVE YOU) AND DON'T YOU FORGET IT Kirk, Roland Rahsaan (disc 10) (Just) SQUEEZE ME Armstrong, Louis Louis Armstrong (i Grandi del Jazz) Desmond, Paul Like Someone In Love Desmond, Paul Pure Desmond Peterson, Oscar Great Connection 13 TO GO Martino, Pat Stone Blue 17 WEST Dolphy, Eric Dolphy 20 ANOS BLUES Regina, Elis MPB Especial - 1973 204 Ervin, Booker Tex Bookn Tenor 2300 SKIDOO I.C.P. Orchestra T.Monk/E.Nichols 245 Dolphy, Eric Dolphy Dolphy, Eric Unrealized Tapes 26-2 Coltrane, John The Coltrane Legacy Pagina 1 di 412 musicista album 29 SETTEMBRE Malaguti, L., AA.VV. A Night in Italy 3 EAST Abercrombie, John Night 3/4 IN THE AFTERNOON Wheeler, Kenny Deer Wan 34 SKIDOO Evans, Bill Blue in Green Motian, Paul Bill Evans 37 WILLOUGHBY PLACE Grossman, Steve Terra Firma 3-IN-1 WITHOUT THE OIL Kirk, Roland In Europe 1962-67 Kirk, Roland Rahsaan (disc 3) 415 CENTRAL PARK WEST Grossman, Steve Love Is The Thing 5/4 THING Walton, Cedar Eastern Rebellion 500 MILES HIGH 70s Jazz, Pioneers Live Town Hall Purim, Flora 500 Miles High 52+ I.C.P. Orchestra T.Monk/E.Nichols 64 BARS ON WILSHIRE Pagina 2 di 412 musicista album Kessel, Barney Kessel Plays Standards 9:20 SPECIAL Basie, C. Jumpin'at the Woodside Jackson, Milt Milt Jackson A BEAUTIFUL FRIENDSHIP Terry, Clark Milt Jackson Turrentine, Stanley The Look of Love A BLUE TIME Flanagan, Tommy Elusive A BLUES AIN'T NOTHING BUT A TRIP Foster, Frank A Blues ain't Nothing But A Trip A BLUES FOR MICKEY-O Martino, Pat El Hombre A BREATH IN THE WIND Kirk, Roland Rahsaan (disc 3) A CASA De Moraes, Vinicius A Arca de Noé A CERTAIN SMILE Greene, Ted Solo Guitar A CHILD IS BORN Flanagan, Tommy Elusive Montoliu, Tete Sweet'n Lovely V°2 Montoliu, Tete The Music I Like to Play V°2 A CHILD'S BLUES Pagina 3 di 412 musicista album Woods, Phil P. -

Edited by Harriet Monroe FEBRUARY, 1917 Along the South Star Trail

Edited by Harriet Monroe FEBRUARY, 1917 Along the South Star Trail . Frank S. Gordon 221 The Tom-tom—Sa-a Narai—On the War-path—Night In the Desert I-V—Indian Songs Alice Corbin 232 Listening—Buffalo Dance—Where the Fight Was—The Wind—Courtship—Fear—Parting Neither Spirit nor Bird—Prayer to the Mountain Spirit ... Mary Austin 239 Spring to the Earth Witch—Chief Capilano Greets His Namesake at Dawn Constance Lindsay Skinner 242 Poems Edward Eastaway 247 Old Man—The Word—The Unknown Editorial Comment 251 Aboriginal Poetry I-III—Emile Verhaeren Reviews 259 Those Brontes A Book by Lawrence—H. D.'s Vision— War and Womanhood—Translations Notes 274 Copyright 1917 by Harriet Monroe. All rights reserved 543 CASS STREET, CHICAGO $1.50 PER YEAR SINGLE NUMBERS, 16 CENTS Published monthly by Ralph Fletcher Seymour, 1025 Fine Arts Building, Chicago Entered as second-class matter at Postoffice, Chicago. POETRY asks its friends to become Supporting Subscrib ers by paying ten dollars a year to its fund. Next Sep tember will complete the ini tial period of five years for which the magazine was endowed. All who believe in the general purpose and policy of the magazine, and recognize the need and value of such an organ of the art, are invited to assist thus in maintaining it. VOL. IX No. V FEBRUARY, 1917 ALONG THE SOUTH STAR TRAIL Tribal Songs from the South-west THE TOM-TOM DRUM-BEAT, beat of drums, Pebble-rattle in the gourd, Pebble feet on drifting sand . Drum-beat, beat of drums— I have lost the wife-made robe of bear-skin . -

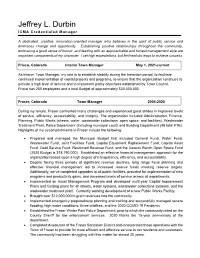

Jeffrey L. Durbin ICMA Credentialed Manager

Jeffrey L. Durbin ICMA Credentialed Manager A dedicated, creative, innovation-oriented manager who believes in the spirit of public service and embraces change and opportunity. Establishing positive relationships throughout the community, embracing a good sense of humor, and leading with an approachable and honest management style are important components of my character. I set high expectations, but find realistic ways to achieve success. Frisco, Colorado Interim Town Manager May 1, 2021-current As Interim Town Manager, my role is to establish stability during the transition period, to facilitate continued implementation oF capital projects and programs, to ensure that the organization continues to provide a high level of service and to implement policy objectives established by Town Council. Frisco has 250 employees and a total Budget of approximately $30,000,000. Fraser, Colorado Town Manager 2004-2020 During my tenure, Fraser conFronted many challenges and experienced great strides in improved levels of service, efFiciency, accountability, and integrity. The organization included Administration, Finance, Planning, Public Works (streets, water, wastewater collections, open space, and Facilities), Wastewater Treatment Plant, Police Department (including municipal court) and Building Department (48 total FTE). Highlights oF my accomplishments in Fraser include the following: • Prepared and managed the Municipal Budget that included General Fund, Water Fund, Wastewater Fund, Joint Facilities Fund, Capital Equipment Replacement Fund, Capital Asset Fund, Debt Service Fund, Restricted Revenue Fund, and the Cozens Ranch Open Space Fund (2020 Budget is $18,790,000). Established an efFective Financial management approach for the organization based upon a high degree of transparency, efFiciency, and accountability. • Despite Facing three periods of signiFicant revenue declines, long range fiscal planning and efFective Financial management led to increased reserve funds meeting reserve targets. -

Voices of Witness, Messages of Hope: Moral Development Theory and Transactional Response in a Literature-Based Holocaust Studies Curriculum

VOICES OF WITNESS, MESSAGES OF HOPE: MORAL DEVELOPMENT THEORY AND TRANSACTIONAL RESPONSE IN A LITERATURE-BASED HOLOCAUST STUDIES CURRICULUM DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alexander Anthony Hernandez, B.A., M.Ed. ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Professor Janet Hickman, Advisor Approved by: Professor Evelyn B. Freeman Professor Anna O. Soter ________________________ Adviser College of Education Copyright by Alexander Anthony Hernandez 2004 ABSTRACT The professional literature of the Holocaust is replete with research, references, and recommendations that a study of the Holocaust, particularly for middle and high school students, is most effective when combined with an extensive use of Holocaust literature. Scholars and educators alike advocate the use of first-person testimony whenever and wherever possible in order to personalize the Holocaust lessons for the student. This study explore students’ responses to first-person Holocaust narratives through the lens of reader response theory in order to determine if prolonged engagement with the literature enhances affective learning. This study also explores the students’ sense of personal ethics and their perceptions on moral decision-making. By examining their responses during prolonged engagement with first-person narratives, herein referred to as witness narratives, and evaluating these responses based on moral development theories developed by Kohlberg and Gilligan, the study also seeks to determine whether there are significant differences in the nature of response that can be attributed to gender. Lastly, the study explores students’ views on racism, and how or if an extended lesson on the Holocaust causes affective change in students’ perceptions of racism and their role in combating it within our society. -

Recorded Jazz in the Early 21St Century

Recorded Jazz in the Early 21st Century: A Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull. Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 The Consumer Guide: People....................................................................................................................7 The Consumer Guide: Groups................................................................................................................119 Reissues and Vault Music.......................................................................................................................139 Introduction: 1 Introduction This book exists because Robert Christgau asked me to write a Jazz Consumer Guide column for the Village Voice. As Music Editor for the Voice, he had come up with the Consumer Guide format back in 1969. His original format was twenty records, each accorded a single-paragraph review ending with a letter grade. His domain was rock and roll, but his taste and interests ranged widely, so his CGs regularly featured country, blues, folk, reggae, jazz, and later world (especially African), hip-hop, and electronica. Aside from two years off working for Newsday (when his Consumer Guide was published monthly in Creem), the Voice published his columns more-or-less monthly up to 2006, when new owners purged most of the Senior Editors. Since then he's continued writing in the format for a series of Webzines -- MSN Music, Medium, -

00131 1 2 3 4 5 6 Federal Subsistence Board Meeting

00131 1 2 3 4 5 6 FEDERAL SUBSISTENCE BOARD MEETING 7 8 MAY 21, 2003 9 10 VOLUME II 11 12 Millennium Hotel 13 Anchorage, Alaska 14 15 BOARD MEMBERS PRESENT: 16 17 Mitch Demientieff, Chairman 18 Gary Edwards, Fish and Wildlife Service 19 Dr. Wini Kessler, Forest Service 20 Henri Bisson, Bureau of Land Management 21 Judy Gottlieb, National Park Service 22 Niles Cesar, Bureau of Indian Affairs 23 24 Keith Goltz, Solicitor 00132 1 P R O C E E D I N G S 2 3 (Anchorage, Alaska - 5/21/2003) 4 5 CHAIRMAN DEMIENTIEFF: Okay. We'll go 6 ahead and call the meeting to order. I believe, Mike, you 7 had some issues that we were going to open with on 8 non-agenda items? 9 10 MR. SMITH: Yeah. Thank you, Mr. Chairman. 11 Once again my name is Mike Smith, and I'm here today 12 representing Tanana Chiefs Conference. 13 14 And I'd like to just address the -- what is 15 called the draft Regulatory Coordination Protocol. That 16 was -- it was a small report stuck in the RAC books at the 17 last fall meetings. I've got copies here if you guys don't 18 have one currently available in front of you. 19 20 And I'd just like to express at this time 21 TCC's concerns in the direction that this particular 22 portion of the MOA is going. Tanana Chiefs is a little 23 concern that the -- what -- that the draft called for the 24 una -- the establishment of an additional board.