Dvoretsky Lessons 15

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONTENTS Contents

CONTENTS Contents Symbols 5 Preface 6 Introduction 9 1 Glossary of Attacking and Strategic Terms 11 2 Double Attack 23 2.1: Double Attacks with Queens and Rooks 24 2.2: Bishop Forks 31 2.3: Knight Forks 34 2.4: The Í+Ì Connection 44 2.5: Pawn Forks 45 2.6: The Discovered Double Attack 46 2.7: Another Type of Double Attack 53 Exercises 55 Solutions 61 3 The Role of the Pawns 65 3.1: Pawn Promotion 65 3.2: The Far-Advanced Passed Pawn 71 3.3: Connected Passed Pawns 85 3.4: The Pawn-Wedge 89 3.5: Passive Sacrifices 91 3.6: The Kamikaze Pawn 92 Exercises 99 Solutions 103 4 Attacking the Castled Position 106 4.1: Weakness in the Castled Position 106 4.2: Rooks and Files 112 4.3: The Greek Gift 128 4.4: Other Bishop Sacrifices 133 4.5: Panic on the Long Diagonal 143 4.6: The Knight Sacrifice 150 4.7: The Exchange Sacrifice 162 4.8: The Queen Sacrifice 172 Exercises 176 Solutions 181 5 Drawing Combinations 186 5.1: Perpetual Check 186 5.2: Repetition of Position 194 5.3: Stalemate 197 5.4: Fortress and Blockade 202 5.5: Positional Draws 204 Exercises 207 Solutions 210 6 Combined Tactical Themes 213 6.1: Material, Endings, Zugzwang 214 6.2: One Sacrifice after Another 232 6.3: Extraordinary Combinations 242 6.4: A Diabolical Position 257 Exercises 260 Solutions 264 7 Opening Disasters 268 7.1: Open Games 268 7.2: Semi-Open Games 274 7.3: Closed Games 288 8 Tactical Examination 304 Test 1 306 Test 2 308 Test 3 310 Test 4 312 Test 5 314 Test 6 316 Hints 318 Solutions 320 Index of Names 331 Index of Openings 335 THE ROLE OF THE PAWNS 3 The Role of the Pawns Ever since the distant days of the 18th century 3.1: Pawn Promotion (let us call it the time of the French Revolution, or of François-André Danican Philidor) we have known that “pawns are the soul of chess”. -

Do First Mover Advantages Exist in Competitive Board Games: the Importance of Zugzwang

DO FIRST MOVER ADVANTAGES EXIST IN COMPETITIVE BOARD GAMES: THE IMPORTANCE OF ZUGZWANG Douglas L. Micklich Illinois State University [email protected] ABSTRACT to the other player(s) in the game (Zagal, et.al., 2006) Examples of such games are chess and Connect-Four. The players try to The ability to move first in competitive games is thought to be secure some sort of first-mover advantage in trying to attain the sole determinant on who wins the game. This study attempts some advantage of position from which a lethal attack can be to show other factors which contribute and have a non-linear mounted. The ability to move first in competitive board games effect on the game’s outcome. These factors, although shown to has thought to have resulted more often in a situation where that be not statistically significant, because of their non-linear player, the one moving first, being victorious. The person relationship have some positive correlations to helping moving first will normally try to take control from the outset and determine the winner of the game. force their opponent into making moves that they would not otherwise have made. This is a strategy which Allis refers to as “Zugzwang”, which is the principle of having to play a move INTRODUCTION one would rather not. To be able to ensure that victory through a gained advantage In Allis’s paper “A Knowledge-Based Approach of is attained, a position must first be determined. SunTzu in the Connect-Four: The Game is Solved: White Wins”, the author “Art of War” described position in this manner: “this position, a states that the player of the black pieces can follow strategic strategic position (hsing), is defined as ‘one that creates a rules by which they can at least draw the game provided that the situation where we can use ‘the individual whole to attack our player of the red pieces does not start in the middle column (the rival’s) one, and many to strike a few’ – that is, to win the (Allis, 1992). -

Electronic Funds Transfer Agreement and Disclosure VISA Checkmate and Electronic Services

Electronic Funds Transfer Agreement and Disclosure VISA CheckMate and Electronic Services This Electronic Fund Transfers Agreement and Disclosure is the contract which covers your and our rights and responsibilities concerning the electronic fund transfers (EFT) services offered to you by University of Virginia Community Credit Union (“Credit Union”). In this Agreement, the words “you,” “your,” and “yours” mean those who sign the application or account card as applicants, joint owners, or any authorized users. The words “we,” “us,” and “our” mean the Credit Union. The word “account” means any one (1) or more share and checking accounts you have with the Credit Union. Electronic fund transfers are electronically initiated transfers of money from your account through the EFT services described below. By signing an application or account card for EFT services, signing your card, or using any service, each of you, jointly and severally, agree to the terms and conditions in this Agreement and any amendments for the EFT services offered. Furthermore, electronic fund transfers that meet the definition of remittance transfers are governed by 12 C.F.R. part 1005, subpart B—Requirements for remittance transfers, and consequently, terms of this agreement may vary for those types of transactions. A “remittance transfer” is an electronic transfer of funds of more than $15.00 which is requested by a sender and sent to a designated recipient in a foreign country by a remittance transfer provider. Terms applicable to such transactions may vary from those disclosed herein and will be disclosed to you at the time such services are requested and rendered in accordance with applicable law. -

Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA

First Steps : Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA www.everymanchess.com About the Author Cyrus Lakdawala is an International Master, a former National Open and American Open Cham- pion, and a six-time State Champion. He has been teaching chess for over 30 years, and coaches some of the top junior players in the U.S. Also by the Author: Play the London System A Ferocious Opening Repertoire The Slav: Move by Move 1...d6: Move by Move The Caro-Kann: Move by Move The Four Knights: Move by Move Capablanca: Move by Move The Modern Defence: Move by Move Kramnik: Move by Move The Colle: Move by Move The Scandinavian: Move by Move Botvinnik: Move by Move The Nimzo-Larsen Attack: Move by Move Korchnoi: Move by Move The Alekhine Defence: Move by Move The Trompowsky Attack: Move by Move Carlsen: Move by Move The Classical French: Move by Move Larsen: Move by Move 1...b6: Move by Move Bird’s Opening: Move by Move Petroff Defence: Move by Move Fischer: Move by Move Anti-Sicilians: Move by Move Opening Repertoire ... c6 First Steps: the Modern 3 Contents About the Author 3 Bibliography 5 Introduction 7 1 Essential Knowledge 9 2 Pawn Endings 23 3 Rook Endings 63 4 Queen Endings 119 5 Bishop Endings 144 6 Knight Endings 172 7 Minor Piece Endings 184 8 Rooks and Minor Pieces 206 9 Queen and Other Pieces 243 4 Introduction Why Study Chess at its Cellular Level? A chess battle is no less intense for its lack of brevity. Because my messianic mission in life is to make the chess board a safer place for students and readers, I break the seal of confessional and tell you that some students consider the idea of enjoyable endgame study an oxymoron. -

Dvoretsky Lessons 12

The Instructor Tragicomedies in Pawn Endgames “Pawn endgames are rare birds in practice. Players avoid them, because they do not like them, because they do not understand them. It’s certainly no secret that pawn endings are ‘terra incognita’ - even for many masters, right up to the level of grandmasters and world champions.” N. Grigoriev Herewith, I offer proof that these words, spoken by a famous expert on pawn endings, are true. Without commentary, I give below the final moves of some actual games, and offer the readers the chance to comment on them, to uncover all the mistakes committed by both players. The endgames you will be dealing with here are not all that difficult; but still, the players on both sides have The provided you with plenty of opportunities for critical commentary. 1...Kf8 2. Qf5+ Qxf5 3. gf Kg7 4. c4 f3 5. h6+ Kxh6 6. c5 dc 7. f6 Kg6 Instructor White resigned. Mark Dvoretsky 1...g5 2. Kf3 Kd5 3. c6 Kd6 4. Ke4 a6 5. ba Kxc6 6. Kf3 Kb6 7. h4 gh 8. Kg4 Kxa6 9. Kxh4 Kb6 10. Kg4 Kc6 11. h4 Kd6. White resigned. file:///C|/Cafe/Dvoretsky/dvoretsky.htm (1 of 9) [9/11/2001 7:09:02 AM] The Instructor 1. Kh7 Kf7 2. Kh8 Kf8 3. g5. Black resigned. 1. Kg5 Kf8 2. Kxf5 Kf7 3. Kg4 Kf6 4. Kf4 Kf7 5. Kf5 Ke7 6. Ke5 Kf7 7. Kd6 Kf6 8. Kd7 Kf7 9. h6 Kg6 10. f4 Kf7 11. f5 Kf6 Drawn Gazic - Petursson European Junior Championship, Groningen 1978/79 The draw is obvious after 1...Kh8! Black mistakenly allowed the trade of queens. -

Virginia Chess Federation 2008 - #6

VIRGINIA CHESS Newsletter The bimonthly publication of the Virginia Chess Federation 2008 - #6 Grandmaster Larry Kaufman See page 1 VIRGINIA CHESS Newsletter 2008 - Issue #6 Editor: Circulation: Macon Shibut Ernie Schlich 8234 Citadel Place 1370 South Braden Crescent Vienna VA 22180 Norfolk VA 23502 [email protected] [email protected] k w r Virginia Chess is published six times per year by the Virginia Chess Federation. Membership benefits (dues: $10/yr adult; $5/yr junior under 18) include a subscription to Virginia Chess. Send material for publication to the editor. Send dues, address changes, etc to Circulation. The Virginia Chess Federation (VCF) is a non-profit organization for the use of its members. Dues for regular adult membership are $10/yr. Junior memberships are $5/yr. President: Mike Hoffpauir, 405 Hounds Chase, Yorktown VA 23693, mhoffpauir@ aol.com Treasurer: Ernie Schlich, 1370 South Braden Crescent, Norfolk VA 23502, [email protected] Secretary: Helen Hinshaw, 3430 Musket Dr, Midlothian VA 23113, jallenhinshaw@comcast. net Scholastics Coordinator: Mike Hoffpauir, 405 Hounds Chase, Yorktown VA 23693, [email protected] VCF Inc. Directors: Helen Hinshaw (Chairman), Rob Getty, John Farrell, Mike Hoffpauir, Ernie Schlich. otjnwlkqbhrp 2008 - #6 1 otjnwlkqbhrp Larry Kaufman, of Maryland, is a familiar face at Virginia tournaments. Among others he won the Virginia Open in 1969, 1998, 2000, 2006 and 2007! Recently Larry achieved a lifelong goal by attaining the title of International Grandmaster, and agreed to tell VIRGINIA CHESS readers how it happened. -ed World Senior Chess Championship by Larry Kaufman URING THE LAST FIVE YEARS OR SO, whenever someone asked me Dif I still hoped to become a GM, I would reply something like this: “I’m too old now to try to do it the normal way, but perhaps when I reach 60 I will try to win the World Senior, which carries an automatic GM title. -

CHECKMATE PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): March 29, 2021 CHECKMATE PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 001-39425 36-4813934 (State or other jurisdiction (Commission (I.R.S. Employer of incorporation) File Number) Identification No.) Checkmate Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 245 Main Street, 2nd Floor Cambridge, MA 02142 (Address of principal executive offices, including zip code) (617) 682-3625 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Not Applicable (Former Name or Former Address, if Changed Since Last Report) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: ☐ Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) ☐ Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Trade Name of each exchange Title of each class Symbol(s) on which registered Common Stock, $0.0001 par value per share CMPI The Nasdaq Global Market Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is an emerging growth company as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933 (§ 230.405 of this chapter) or Rule 12b-2 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (§ 240.12b-2 of this chapter). -

The Exchange French Comes to Life

The Exchange French Comes to Life Fresh Strategies to Play for a Win Alex Fishbein Foreword by John Watson 2021 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 1 The Exchange French Comes to Life Fresh Strategies to Play for a Win ISBN: 978-1-949859-29-4 (print) ISBN: 978-1-949859-30-0 (eBook) © Copyright 2021 Alex Fishbein All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. P.O. Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Cover by Fierce Ponies Printed in the United States of America 2 Table of Contents Signs and Symbols 6 Preface 7 Foreword by John Watson 10 Chapter 1 Introduction to the Exchange French 13 Chapter 2 The IQP-lite 33 Chapter 3 The Uhlmann Gambit 72 Chapter 4 Symmetrical Structures 95 Chapter 5 The 5...c5 Variation 139 Chapter 6 The 4...Bg4 Variation 149 Chapter 7 The 4...Nc6 Variation 163 Chapter 8 Rare Moves against 4.Nf3 190 Chapter 9 The Miezis Variation 199 Chapter 10 The Delayed Exchange Variation 211 3 The Exchange French Comes to Life Chapter 11 Your Repertoire File 224 Index of Variations 235 Bibliography 239 Frequently Occurring Strategic Themes 240 4 Preface The Exchange French is nothing close to a draw! The Exchange French has long had the reputation of a boring and drawish opening. -

Fischer Notches Another

FISCHER NOTCHES ANOTHER * (See p. 235) I >:;: UNITED STATES Volume XVJ1l Numher 10 Oclober, 1963 EDITOR: J . F. Reinhardt - U. S. Championship Starts Dec. 15 The 1963-64 United States Championship will be played in New York City from CHESS FEDERATION Sunday, December 15 through ThUt'sday, January 2. As last year, the tournament l' ite will be the Henry Hudson Hotel, 353 W. 57th St. Sunday rounds will be played at 2 p.m.; weekday rounds at 7 p.m.; Saturday rounds at 7:30 p.m. PRESIDENT As we go to press, Bobby Fischer has announced that he wilt defend his title. Major Edmund B. Edmondson, Jr. Others who have accepted invitations to play are Samuel Reshevsky, Donald Byrne, Rohert Byrne, Larry Evans, Pal Benko, and Dr. Anthony Saidy. VICE·PRESIDENT Unfortunately, U. S. Open Champion William L.ombardy will again be unable to David Hoffmann pluy in the event because of his studies. REGIONAL VICE·PRESIDENTS Further details of the U. S. Championsbip...-.including the complete schedule NEW ENGLAND Ell Bourdon will appear in our next issue. Jam.es Burgess Stanley King EASTERN Open Crosstable In Next Issue MID·ATLANTIC Fred Towruend Since we wanted to get the full minutes of the Chicago Business Meetings on George Thomas record as soon as possible, and since this iss ue contains an extra Rating Supplement, William S. Byland we have had to defer running the full crosstable of the record·breaking U. S. Open SOUTHERN Dr. Stuart KOhlln IIntil our November issue. We're sorry for the delay but- even though this is a 32- Jerry Sullivan Dr. -

Glossary of Chess

Glossary of chess See also: Glossary of chess problems, Index of chess • X articles and Outline of chess • This page explains commonly used terms in chess in al- • Z phabetical order. Some of these have their own pages, • References like fork and pin. For a list of unorthodox chess pieces, see Fairy chess piece; for a list of terms specific to chess problems, see Glossary of chess problems; for a list of chess-related games, see Chess variants. 1 A Contents : absolute pin A pin against the king is called absolute since the pinned piece cannot legally move (as mov- ing it would expose the king to check). Cf. relative • A pin. • B active 1. Describes a piece that controls a number of • C squares, or a piece that has a number of squares available for its next move. • D 2. An “active defense” is a defense employing threat(s) • E or counterattack(s). Antonym: passive. • F • G • H • I • J • K • L • M • N • O • P Envelope used for the adjournment of a match game Efim Geller • Q vs. Bent Larsen, Copenhagen 1966 • R adjournment Suspension of a chess game with the in- • S tention to finish it later. It was once very common in high-level competition, often occurring soon af- • T ter the first time control, but the practice has been • U abandoned due to the advent of computer analysis. See sealed move. • V adjudication Decision by a strong chess player (the ad- • W judicator) on the outcome of an unfinished game. 1 2 2 B This practice is now uncommon in over-the-board are often pawn moves; since pawns cannot move events, but does happen in online chess when one backwards to return to squares they have left, their player refuses to continue after an adjournment. -

The Exchange French Comes to Life

The Exchange French Comes to Life Fresh Strategies to Play for a Win Alex Fishbein Foreword by John Watson 2021 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 1 The Exchange French Comes to Life Fresh Strategies to Play for a Win ISBN: 978-1-949859-29-4 (print) ISBN: 978-1-949859-30-0 (eBook) © Copyright 2021 Alex Fishbein All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. P.O. Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Cover by Fierce Ponies Printed in the United States of America 2 Table of Contents Signs and Symbols 6 Preface 7 Foreword by John Watson 10 Chapter 1 Introduction to the Exchange French 13 Chapter 2 The IQP-lite 33 Chapter 3 The Uhlmann Gambit 72 Chapter 4 Symmetrical Structures 95 Chapter 5 The 5...c5 Variation 139 Chapter 6 The 4...Bg4 Variation 149 Chapter 7 The 4...Nc6 Variation 163 Chapter 8 Rare Moves against 4.Nf3 190 Chapter 9 The Miezis Variation 199 Chapter 10 The Delayed Exchange Variation 211 3 The Exchange French Comes to Life Chapter 11 Your Repertoire File 224 Index of Variations 235 Bibliography 239 Frequently Occurring Strategic Themes 240 4 Preface The Exchange French is nothing close to a draw! The Exchange French has long had the reputation of a boring and drawish opening. -

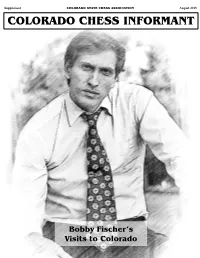

Bobby Fischer's Visits to Colorado – Colorado Chess Informant

Supplement COLORADO STATE CHESS ASSOCIATION August 2018 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT Bobby Fischer’s Visits to Colorado Supplement Colorado Chess Informant August 2018 COLORADO CHESS HISTORY - BOBBY FISCHER’S VISITS by National Master Todd Bardwick This supplement to the Informant is an attempt to give a detailed historical account of Bobby Fischer’s visits to Colorado for current and future generations. I have written many articles about it in the Rocky Mountain News over the 17 years I wrote for the newspaper. (To find thoses articles, you can go to www.ColoradoMasterChess.com and click on the Articles link.) This became a much bigger project that I originally anticipated as the list of people to talk to grew. It became a real life “Searching for Bobby Fischer”, just 47 years later. My research on the subject started back in the early to mid 1990s while visiting John Howell. John’s contributions to Colorado chess as an organizer where monumental. I realized that the stories he told were of huge historical significance to the history of Colorado chess. Today, I wish my notes of our conversations were even more detailed and, looking back, there is a lot more I would like to ask him. John passed away on March 7, 2000 at the age of 88. Cathy Howell, John’s daughter, recently helped me to fill in some of the blanks, provided a copy of some of the notes from John’s diaries (he kept a detailed diary for most days of his adult life!), and gave me chess articles and photos from his files dating back into the 1960s which are posted on the History Section of the Colorado State Chess Association website.