Castling in the Square the Harvard Chess Club Battles the Clock and the Competition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Column and CC News

1.e4 d5 2.e5 e6 3.d4 Nc6 4.Nf3 Bb4+ 5.c3 Be7 6.g3 Bd7 7.Bd3 ½–½ Counted among the mysteries that I just do not understand... PHILIDOR’S DEFENSE (C41) White: Matthew Ross (800) Black: Paul Rellias The Check Is in the Mail IECG 2005 DECEMBER 2006 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 d6 3. d4 f6 4. Bc4 Ne7 5. This month I honor a 25-year old dxe5 fxe5 6. 00 Bg4 7. Nxe5 Rg8 8. tradition of featuring miniature games in Bxg8 h6 9. Bf7 mate “The Check”. You may find it surprising that miniature games can Sometimes postal chess is an easy game happen to all ranks of chess players. – you just follow book for 10 to 15 They do, and here is the proof. The moves or so, and when your opponent February issue of Chess Life will also thinks for himself, you’ve got ‘em! contain some of these snowflakes, little wonders of nature. SICILIAN DEFENSE (B99) White: Olita Rause (2720) There are more tactics in this mini than Black: Vladimir Hefka (2574) you will find in three regular-sized 18th World Championship, 2003 games. 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 RUY LOPEZ (C70) 5.Nc3 a6 6.Bg5 e6 7.f4 Be7 8.Qf3 Qc7 White: Nowden 9.0–0–0 Nbd7 10.g4 b5 11.Bxf6 Nxf6 Black: Kristensen 12.g5 Nd7 13.f5 Nc5 14.f6 gxf6 15.gxf6 Correspondence 1933 Bf8 16.Rg1 h5 17.a3 Bd7 18.Kb1 Bc6 19.Bh3 Qb7 20.b4 1-0 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Ba4 Bc5 5.c3 b5 6.Bc2 d5 7.d4 exd4 8.cxd4 Bb6 9.0–0 Bg4 10.exd5 Qxd5 11.Be4 Qd7 12.Qe1 0–0–0 13.Bxc6 Qxc6 14.Ne5 XABCDEFGHY Qe6 15.Qe4 c6 16.Qxg4 f5 17.Qxg7 8 +-+- ( Bxd4 18.Bf4 Bxb2 19.Nc3 Bxa1 20.Qa7 1–0 7++-++-' 6+-+& Two amateurs distill the essence of the 5+-+-+% Grandmaster draw. -

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65 COMPUTER ANALYSIS OF WORLD CHESS CHAMPIONS1 Matej Guid2 and Ivan Bratko2 Ljubljana, Slovenia ABSTRACT Who is the best chess player of all time? Chess players are often interested in this question that has never been answered authoritatively, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. In this contribution, we attempt to make such a comparison. It is based on the evaluation of the games played by the World Chess Champions in their championship matches. The evaluation is performed by the chess-playing program CRAFTY. For this purpose we slightly adapted CRAFTY. Our analysis takes into account the differences in players' styles to compensate the fact that calm positional players in their typical games have less chance to commit gross tactical errors than aggressive tactical players. Therefore, we designed a method to assess the difculty of positions. Some of the results of this computer analysis might be quite surprising. Overall, the results can be nicely interpreted by a chess expert. 1. INTRODUCTION Who is the best chess player of all time? This is a frequently posed and interesting question, to which there is no well founded, objective answer, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. With the emergence of high-quality chess programs a possibility of such an objective comparison arises. However, so far computers were mostly used as a tool for statistical analysis of the players' results. Such statistical analyses often do neither reect the true strengths of the players, nor do they reect their quality of play. -

Deep Fritz 11 Rating

Deep fritz 11 rating CCRL 40/4 main list: Fritz 11 has no rank with rating of Elo points (+9 -9), Deep Shredder 12 bit (+=18) + 0 = = 0 = 1 0 1 = = = 0 0 = 0 = = 1 = = 1 = = 0 = = 0 1 0 = 0 1 = = 1 1 = – Deep Sjeng WC bit 4CPU, , +12 −13, (−65), 24 − 13 (+13−2=22). %. This is one of the 15 Fritz versions we tested: Compare them! . − – Deep Sjeng bit, , +22 −22, (−15), 19 − 15 (+13−9=12). % / Complete rating list. CCRL 40/40 Rating List — All engines (Quote). Ponder off Deep Fritz 11 4CPU, , +29, −29, %, −, %, %. Second on the list is Deep Fritz 11 on the same hardware, points below The rating list is compiled by a Swedish group on the basis of. Fritz is a German chess program developed by Vasik Rajlich and published by ChessBase. Deep Fritz 11 is eighth on the same list, with a rating of Overall the answer for what to get is depending on the rating Since I don't have Rybka and I do have Deep Fritz 11, I'll vote for game vs Fritz using Opening or a position? - Chess. Find helpful customer reviews and review ratings for Fritz 11 Chess Playing Software for PC at There are some algorithms, from Deep fritz I have a small Engine Match database and use the Fritz 11 Rating Feature. Could somebody please explain the logic behind the algorithm? Chess games of Deep Fritz (Computer), career statistics, famous victories, opening repertoire, PGN download, Feb Version, Cores, Rating, Rank. DEEP Rybka playing against Fritz 11 SE using Chessbase We expect, that not only the rating figures, but also the number of games and the 27, Deep Fritz 11 2GB Q 2,4 GHz, , 18, , , 62%, Deep Fritz. -

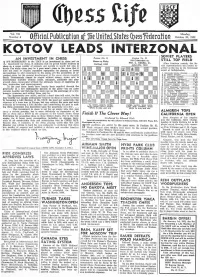

Kolov LEADS INTERZONAL SOVIET PLAYERS an INVESTMENT in CHESS Po~;T;On No

Vol. Vll Monday; N umber 4 Offjeitll Publication of me Unttecl States (bessTederation October 20, 1952 KOlOV LEADS INTERZONAL SOVIET PLAYERS AN INVESTMENT IN CHESS Po~;t;on No. 91 POI;l;"n No. 92 IFE MEMBERSHIP in the USCF is an investment in chess and an Euwe vs. Flohr STILL TOP FIELD L investment for chess. It indicates that its proud holder believes in C.1rIbad, 1932 After fOUl't~n rounds, the S0- chess ns a cause worthy of support, not merely in words but also in viet rcpresentatives still erowd to deeds. For while chess may be a poor man's game in the sense that it gether at the top in the Intel'l'onal does not need or require expensive equipment fm' playing or lavish event at Saltsjobaden. surroundings to add enjoyment to the game, yet the promotion of or· 1. Alexander Kot()v (Russia) .w._.w .... 12-1 ganized chess for the general development of the g'lmc ~ Iway s requires ~: ~ ~~~~(~tu(~~:I;,.i ar ·::::~ ::::::::::~ ~!~t funds. Tournaments cannot be staged without money, teams sent to international matches without funds, collegiate, scholastic and play· ;: t.~h!"'s~~;o il(\~::~~ ry i.. ··::::::::::::ij ); ~.~ ground chess encouraged without the adequate meuns of liupplying ad· 6. Gidcon S tahl ~rc: (Sweden) ...... 81-5l vice, instruction and encouragement. ~: ~,:ct.~.:~bG~~gO~~(t3Ji;Oi· · ·:::: ::::::7i~~ In the past these funds have largely been supplied through the J~: ~~j~hk Elrs'l;~san(A~~;t~~~ ) ::::6i1~ generosity of a few enthusiastic patrons of the game-but no game 11. -

Taming Wild Chess Openings

Taming Wild Chess Openings How to deal with the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly over the chess board By International Master John Watson & FIDE Master Eric Schiller New In Chess 2015 1 Contents Explanation of Symbols ���������������������������������������������������������������� 8 Icons ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 Introduction �������������������������������������������������������������������������� 10 BAD WHITE OPENINGS ��������������������������������������������������������������� 18 Halloween Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♘c3 ♘f6 4.♘xe5 ♘xe5 5.d4 . 18 Grünfeld Defense: The Gibbon: 1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 g6 3.♘c3 d5 4.g4 . 20 Grob Attack: 1.g4 . 21 English Wing Gambit: 1.c4 c5 2.b4 . 25 French Defense: Orthoschnapp Gambit: 1.e4 e6 2.c4 d5 3.cxd5 exd5 4.♕b3 . 27 Benko Gambit: The Mutkin: 1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 c5 3.d5 b5 4.g4 . 28 Zilbermints - Benoni Gambit: 1.d4 c5 2.b4 . 29 Boden-Kieseritzky Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗c4 ♘f6 4.♘c3 ♘xe4 5.0-0 . 31 Drunken Hippo Formation: 1.a3 e5 2.b3 d5 3.c3 c5 4.d3 ♘c6 5.e3 ♘e7 6.f3 g6 7.g3 . 33 Kadas Opening: 1.h4 . 35 Cochrane Gambit 1: 5.♗c4 and 5.♘c3 . 37 Cochrane Gambit 2: 5.d4 Main Line: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘f6 3.♘xe5 d6 4.♘xf7 ♔xf7 5.d4 . 40 Nimzowitsch Defense: Wheeler Gambit: 1.e4 ♘c6 2.b4 . 43 BAD BLACK OPENINGS ��������������������������������������������������������������� 44 Khan Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♗c4 d5 . 44 King’s Gambit: Nordwalde Variation: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 ♕f6 . 45 King’s Gambit: Sénéchaud Countergambit: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 ♗c5 3.♘f3 g5 . -

Game Room Tables 2020 Game Room Tables

Game Room Tables 2020 Game Room Tables At SilverLine, our goal is to build fine furniture that will be a family heirloom – for your family and your children’s families, in the old world tradition of our ancestors. Manufactured with quality North American hardwoods, our pool tables and game tables are handcrafted and constructed for years of play. We have several styles and sizes available. Can’t find the perfect table or accessory? Let us create a piece of furniture just for you! Pool tables feature: • 1" framed slate • 22oz. cloth in over 20 colors • 12 pocket choices • Available in 7', 8', or 9' lengths Our tables are available in many custom finishes, or we can match your existing furniture. SILVERLINE, INC 2 game room furniture | 2020 Index POOL TABLES Breckenridge ................................................. 4 CHESS TABLES Caldwell ........................................................ 4 Allendale Chess Table ................................... 14 Caledonia ....................................................... 5 Ashton Chess Table ....................................... 14 Classic Mission ............................................... 5 Landmark Mission ......................................... 6 FOOSBALL Monroe .......................................................... 6 Alpine Foosball Table ................................... 15 Regal ............................................................. 7 Signature Mission Foosball Table .................. 15 Shaker Hill .................................................... 7 -

11 Triple Loyd

TTHHEE PPUUZZZZLLIINNGG SSIIDDEE OOFF CCHHEESSSS Jeff Coakley TRIPLE LOYDS: BLACK PIECES number 11 September 22, 2012 The “triple loyd” is a puzzle that appears every few weeks on The Puzzling Side of Chess. It is named after Sam Loyd, the American chess composer who published the prototype in 1866. In this column, we feature positions that include black pieces. A triple loyd is three puzzles in one. In each part, your task is to place the black king on the board.to achieve a certain goal. Triple Loyd 07 w________w áKdwdwdwd] àdwdwdwdw] ßwdwdw$wd] ÞdwdRdwdw] Ýwdwdwdwd] Üdwdwdwdw] Ûwdwdpdwd] Údwdwdwdw] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Place the black king on the board so that: A. Black is in checkmate. B. Black is in stalemate. C. White has a mate in 1. For triple loyds 1-6 and additional information on Sam Loyd, see columns 1 and 5 in the archives. As you probably noticed from the first puzzle, finding the stalemate (part B) can be easy if Black has any mobile pieces. The black king must be placed to take away their moves. Triple Loyd 08 w________w áwdwdBdwd] àdwdRdwdw] ßwdwdwdwd] Þdwdwdwdw] Ýwdw0Ndwd] ÜdwdPhwdw] ÛwdwGwdwd] Údwdw$wdK] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Place the black king on the board so that: A. Black is in checkmate. B. Black is in stalemate. C. White has a mate in 1. The next triple loyd sets a record of sorts. It contains thirty-one pieces. Only the black king is missing. Triple Loyd 09 w________w árhbdwdwH] àgpdpdw0w] ßqdp!w0B0] Þ0ndw0PdN] ÝPdw4Pdwd] ÜdRdPdwdP] Ûw)PdwGPd] ÚdwdwIwdR] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Place the black king on the board so that: A. -

2009 U.S. Tournament.Our.Beginnings

Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis Presents the 2009 U.S. Championship Saint Louis, Missouri May 7-17, 2009 History of U.S. Championship “pride and soul of chess,” Paul It has also been a truly national Morphy, was only the fourth true championship. For many years No series of tournaments or chess tournament ever held in the the title tournament was identi- matches enjoys the same rich, world. fied with New York. But it has turbulent history as that of the also been held in towns as small United States Chess Championship. In its first century and a half plus, as South Fallsburg, New York, It is in many ways unique – and, up the United States Championship Mentor, Ohio, and Greenville, to recently, unappreciated. has provided all kinds of entertain- Pennsylvania. ment. It has introduced new In Europe and elsewhere, the idea heroes exactly one hundred years Fans have witnessed of choosing a national champion apart in Paul Morphy (1857) and championship play in Boston, and came slowly. The first Russian Bobby Fischer (1957) and honored Las Vegas, Baltimore and Los championship tournament, for remarkable veterans such as Angeles, Lexington, Kentucky, example, was held in 1889. The Sammy Reshevsky in his late 60s. and El Paso, Texas. The title has Germans did not get around to There have been stunning upsets been decided in sites as varied naming a champion until 1879. (Arnold Denker in 1944 and John as the Sazerac Coffee House in The first official Hungarian champi- Grefe in 1973) and marvelous 1845 to the Cincinnati Literary onship occurred in 1906, and the achievements (Fischer’s winning Club, the Automobile Club of first Dutch, three years later. -

FIDE Laws of Chess

FIDE Laws of Chess FIDE Laws of Chess cover over-the-board play. The Laws of Chess have two parts: 1. Basic Rules of Play and 2. Competition Rules. The English text is the authentic version of the Laws of Chess (which was adopted at the 84th FIDE Congress at Tallinn (Estonia) coming into force on 1 July 2014. In these Laws the words ‘he’, ‘him’, and ‘his’ shall be considered to include ‘she’ and ‘her’. PREFACE The Laws of Chess cannot cover all possible situations that may arise during a game, nor can they regulate all administrative questions. Where cases are not precisely regulated by an Article of the Laws, it should be possible to reach a correct decision by studying analogous situations which are discussed in the Laws. The Laws assume that arbiters have the necessary competence, sound judgement and absolute objectivity. Too detailed a rule might deprive the arbiter of his freedom of judgement and thus prevent him from finding a solution to a problem dictated by fairness, logic and special factors. FIDE appeals to all chess players and federations to accept this view. A necessary condition for a game to be rated by FIDE is that it shall be played according to the FIDE Laws of Chess. It is recommended that competitive games not rated by FIDE be played according to the FIDE Laws of Chess. Member federations may ask FIDE to give a ruling on matters relating to the Laws of Chess. BASIC RULES OF PLAY Article 1: The nature and objectives of the game of chess 1.1 The game of chess is played between two opponents who move their pieces on a square board called a ‘chessboard’. -

The Double Queen's Gambit

Alexey Bezgodov The Double Queen’s Gambit A Surprise Weapon for Black New In Chess 2015 Contents Explanation of Symbols .......................................... 6 Introduction .................................................. 7 Part I – White avoids the main variations . 11 Chapter 1 White accepts the gambit ........................14 Chapter 2 The white bishop comes out ......................17 Chapter 3 Transposing into the Alapin Variation of the Sicilian.....24 Chapter 4 Transposition into the Exchange Variation of the Slav Defence 27 Chapter 5 Transposition into the Panov Attack .................37 Part II – Who is tricking whom? 3 .♘f3 . 49. Chapter 6 The rare symmetrical endgame ....................51 Chapter 7 The mysterious black queen check .................56 Chapter 8 The centralised knights system ....................66 Part III – The queenless DQG: 3 .♘f3 cxd4 4 .cxd5 ♘f6 5 .♕xd4 ♕xd5 6 .♘c3 ♕xd4 7 .♘xd4 . 97 Chapter 9 7...a6 – Taking control of the square b5.............100 Chapter 10 7…♗d7 – The bishop-retention system ............129 Chapter 11 7...e5 – The move of the future? ..................143 Part IV – The Gorbatov Gambit and the imaginary Semi-Tarrasch: 3 .♘c3 . 155 Chapter 12 A fascinating gambit ...........................157 Chapter 13 The classical 3...♘f6 ...........................163 Part V – The Deferred Capture Variation: 3 .cxd5 ♘f6 . 177 Chapter 14 White takes on c5 .............................179 Chapter 15 The strong 4.e4...............................187 Chapter 16 An Attempt at Revival ..........................193 Part VI – The main variation: 3 .cxd5 ♕xd5 . 205 Chapter 17 Early divergences..............................208 Chapter 18 The Queen Retreats 5...♕d7/5...♕d8 .............217 Chapter 19 Minor white moves after 6...♘f6..................223 Chapter 20 The fianchetto 7.g3 ............................233 Part VII – Retro-Training . 247 Postscript...............................................278 Bibliography................................................ -

A Semiotic Analysis on Signs of the English Chess Game

1 A Semiotic Analysis on Signs of the English Chess Game M. I. Andi Purnomo, Drs. Wisasongko, M.A., Hat Pujiati, S.S., M.A. English Department, Faculty of Letter, Jember University Jln. Kalimantan 37, Jember 68121 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This thesis discusses about English Chess Game through Roland Barthes's Myth. In this thesis, I use documentary technique as method of analysis. The analysis is done by the observation of the rules, colors, and images of the English chess game. In addition, chessman and chess formation are analyzed using syntagmatic and paradigmatic relation theory to explore the correlation between symbols of the English chess game with the existence of Christian in the middle age of England. The result of this thesis shows the relation of English chess game with the history of England in the middle age where Christian ideology influences the social, military, and government political life of the English empire. Keywords: chessman, chess piece, bishops, king, knights, pawns, queen, rooks. Introduction Then, the game spread into Europe. Around 1200, the game was established in Britain and the name of “Chess” begins Game is an activity that is done by people for some (Shenk, 2006:51). It means chess spread to English during purposes. Some people use the game as a medium of the Middle Ages. The Middle Age of English begins around interaction with other people. Others use the game as the 1066 – 1485 (www.middle-ages.org.uk). At that time, the activity of spending leisure time. Others use the game as the Christian dominated the whole empire and automatically the major activity for professional. -

3 After the Tournament

Important Dates for 2018-19 Important Changes early Sept. Chess Manual & Rule Book posted online TERMS & CONDITIONS November 1 Preliminary list of entries posted online V-E-3 Removes all restrictions on pairing teams at the state December 1 Official Entry due tournament. The result will be that teams from the same Official Entry should be submitted online by conference may be paired in any round. your school’s official representative. V- E-6 Provides that sectional tournament will only be paired There is no entry fee, but late entries will incur after registration is complete so that last-minute with- a $100 late fee. drawals can be taken into account. December 1 Updated list of entries posted online IX-G-4 Clarifies that the use of a smartwatch by a player is ille- gal, with penalties similar to the use of a cell phone. December 1 List of Participants form available online Contact your activities director for your login ID and password. VII-C-1,4,5,6 and VIII-D-1,2,4 Failure to fill out this form by the deadline con- Eliminates individual awards at all levels of the stitutes withdrawal from the tournament. tournament. Eliminates the requirement that a player stay on one board for the entire tournament. Allows January 2 Required rules video posted players to shift up and down to a different board, while January 16 Deadline to view online rules presentation remaining in the "Strength Order" declared by the Deadline to submit List of Participants (final coach prior to the start of the tournament.