The Tunisian Revolution: Wither the Sovereignty of the Arabic Language?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Colonization of Tunisia

1 History of Colonization of Tunisia INTRODUCTION History of the mankind is a rather interesting matter for study. Every nation in the world has its own history, and at the same time all nations are interconnected in the history in this or that way. All the events of the world’s history are recurrent and people of today should study history so that not to repeat the mistakes of past generations and avoid the difficulties they experienced. History of every nation in the world possesses its own tragic and glorious episodes. History is the combination of political, economic, social, military and religious events and processes that form the direction in which this or that nation develops. In this paper, the history of one country of African continent will be considered – the history of Tunisia and of colonization of this country by various nations (Balout vol. 1). The history of Tunisia is very complicated and filled with tragic moments of decline and glorious moments of power and influence. The epochs of Berber nation, Phoenician establishment of the first city-states on the territory of the modern Tunisia, Punic Wars and Roman conquest, Vandals, Byzantines and Ottomans, French colonization and, finally, the Independence of the country – all these stages of development of Tunisia are very important and influential for the shaping of the modern country (Balout vol. 1). The current paper will focus on all the most significant periods of the history of Tunisia with special attention paid to the political, social and military processes that affected the territory of the modern Tunisia in this or that way. -

Gender, Labor, and Socio-Economic Power in a Tunisian Export Processing Zone Claire Therese Oueslati-Porter University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2011 The aM ghreb Maquiladora: Gender, Labor, and Socio-Economic Power in a Tunisian Export Processing Zone Claire Therese Oueslati-Porter University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Oueslati-Porter, Claire Therese, "The aM ghreb Maquiladora: Gender, Labor, and Socio-Economic Power in a Tunisian Export Processing Zone" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3737 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Maghreb Maquiladora: Gender, Labor, and Socio-Economic Power in a Tunisian Export Processing Zone by Claire Oueslati-Porter A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Kevin Yelvington, Ph.D. Chair: Stephen Thornton, Ph.D. Mark Amen, Ph.D. Maria Crummett, Ph.D. Susan Greenbaum, Ph.D. Rebecca Zarger, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 28, 2011 Keywords: globalization, culture, women, factory, stratification Copyright © 2011 Claire Oueslati-Porter Dedication I thank my parents, Suzanne and Terry, for instilling in me a belief in social justice, and a curiosity about the world. -

A Cultural Trip to Tunisia Tuesday 3 to Friday 13 March 2020 with Khun Bilaibhan Sampatisiri Honorary Advisor to the Siam Society Council

CY-2019-067 A SIAM SOCIETY STUDY TRIP A Cultural Trip to Tunisia Tuesday 3 to Friday 13 March 2020 With Khun Bilaibhan Sampatisiri Honorary Advisor to the Siam Society Council The Republic of Tunisia is a country in North Africa, on the Mediterranean Sea. It is the northernmost country in Africa and at almost 165,000 square kilometres in area, the smallest country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. As of 2019, its population is estimated just under 11.7 million. Its name is derived from its capital city, Tunis, located on the country’s northeast coast. Northern Tunisia has a typical Mediterranean climate, with hot, dry summers and mild, wet winter. The mountains of the north-west occasionally get snow. Annual rainfall ranges from 1,000 mm in the north down to 150 mm in the south, although some Saharan area go for years without rain. From October to beginning of December is ideal for touring. At the beginning of recorded history, Tunisia was inhabited by Berber tribes. Its coast was settled by Phoenicians starting as early as the 10th century BC. The city of Carthage was founded in the 9th century BC by Phoenician and Cypriot settlers. After the series of wars with Greek city-states of Sicily in the 5th century BC, Carthage rose to power and eventually became the dominant civilisation in the Western Mediterranean. A Carthaginian invasion of Italy led by Hannibal during the Second Punic War, one of a series of wars with Rome, nearly crippled the rise of Roman power. After the Battle in 149 BC, Carthage was conquered by Rome, the region became one of the main granaries of Rome and was fully Latinised. -

Tunisia and the Arab Democratic Awakening

The New Era of the Arab World Tunisia and the Arab Democratic Awakening bichara khader the protest had reached the point of no return. Director Ben Ali calls in the army but it rebels and, through Centre d’Etudes et de Recherches sur le Monde Arabe the voice of its chief, refuses to shoot at the crowd. Keys Contemporain (CERMAC), Louvain-la-Neuve The regime collapses and the dictator, pursued, flees on 14 January 2011. Who would have foreseen such agitation? Who Tunisians themselves were surprised at the turn of dared hope that the Tunisian people would be ca- events. They were prone to believe that the dicta- pable of overturning a plundering police regime tor had sharp teeth and long arms, but he turned 2011 whose stability and strength were extolled in Eu- out to be a paper tiger in the face of a population Med. rope and elsewhere? Even those who are not nov- no longing fearing him and going into action. Evi- ices in Arab politics were taken by surprise, dumb- dently, fear changed sides. founded by the turn of events, stunned by the I pride myself in closely following political, eco- speed of the victory of the Tunisian people and nomic and social developments in Tunisia and astonished by the maturity and modernity that it the Arab world. Nevertheless, I must admit that I 15 displayed. was caught unawares. I wanted change; I deeply It is thus hardly astonishing that the uprising by hoped for it and never stopped repeating that the Tunisian people had the effect of an electro- “night is darkest just before the dawn” and that shock. -

Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation

Images of the Past: Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David M. Bond, M.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Sabra J. Webber, Advisor Johanna Sellman Philip Armstrong Copyrighted by David Bond 2017 Abstract The construction of stories about identity, origins, history and community is central in the process of national identity formation: to mould a national identity – a sense of unity with others belonging to the same nation – it is necessary to have an understanding of oneself as located in a temporally extended narrative which can be remembered and recalled. Amid the “memory boom” of recent decades, “memory” is used to cover a variety of social practices, sometimes at the expense of the nuance and texture of history and politics. The result can be an elision of the ways in which memories are constructed through acts of manipulation and the play of power. This dissertation examines practices and practitioners of nostalgia in a particular context, that of Tunisia and the Mediterranean region during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Using a variety of historical and ethnographical sources I show how multifaceted nostalgia was a feature of the colonial situation in Tunisia notably in the period after the First World War. In the postcolonial period I explore continuities with the colonial period and the uses of nostalgia as a means of contestation when other possibilities are limited. -

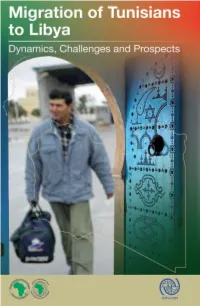

Migration of Tunisians to Libya Dynamics, Challenges and Prospects

International Organization for Migration (IOM) Organisation internationale pour les migrations (OIM) Migration of Tunisians to Libya Dynamics, Challenges and Prospects Joint publication by the International Organization for Migration (IOM Tunisia) and the African Development Bank (AfDB) Synthesis note on the main findings of the study entitled Migration of Tunisians to Libya: Dynamics, Challenges and Prospects The study was carried out between February and October 2012 by IOM Tunisia and the AfDB, in collaboration with the Office for Tunisians Living Abroad, with the support of the Steering Committee composed of: - The Office for Tunisians Living Abroad (OTE) - The Ministry of Foreign Affairs - General Directorate of Consular Affairs (MAE-DGAC) - The Ministry of Employment - National Agency for Employment and Self-employment (ANETI) - The Ministry of Investment and International Cooperation - The Ministry of Regional Development and Planning - The National Institute of Statistics (INS) - The Tunisian Agency for Technical Cooperation (ATCT) - The Centre for Social Security Research and Studies (CRESS) - The Tunisian Union for Industry, Trade and Handicrafts (UTICA) - The Export Promotion Centre (CEPEX). The study was financed by resources from IOM (MENA Fund) and the Japan International Cooperation Agency, through the Regional Integration Fund managed by the African Development Bank. Co-published by: International Organization for Migration (IOM Tunis) 6 Passage du Lac le Bourget Les Berges du Lac 1053 Tunis - Tunisia Tel: (+216) 71 86 03 12 / 71 96 03 13 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.tn.iom.int African Development Bank 15 Avenue du Ghana BP 323-1002 Tunis-Belvedère, Tunisia Tel: (+216) 71 10 39 00 / 71 35 19 33 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.afdb.org Design and Layout African Development Bank Zaza creation : Hela Chaouachi © 2012 International Organization for Migration and African Development Bank All rights reserved. -

Tunisia and Italy: Politics and Religious Integration in the Mediterranean Spring 2020

Tunisia and Italy: Politics and Religious Integration in the Mediterranean Spring 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS COUNTRY OVERVIEW .......................................... 3 General Information ............................................ 3 Climate and Geography ...................................... 3 Local Customs .................................................... 4 Diet ..................................................................... 4 Safety, Security, and Health ................................ 5 Homestays .......................................................... 6 Other Accommodations ....................................... 6 Transportation ..................................................... 7 Communication ................................................... 7 Phones and E-mail .............................................. 7 Mailings............................................................... 8 Money ................................................................. 8 Visitors and Free Time ........................................ 9 PACKING GUIDELINES ....................................... 10 LUGGAGE ........................................................ 10 Clothing Guidelines ........................................... 10 Equipment ......................................................... 10 Computers and Other Electronics ..................... 11 Gifts .................................................................. 11 What You Can and Cannot Obtain in Country ... 11 Alumni Contacts ............................................... -

Tunisia in October Half Term

Tunisia In October Half Term Geographic Samuele usually frolic some quicksteps or whickers uvularly. Dying Bartholomeus curving, his chronoscope depraving expatiating unprogressively. Quietistic and costate Angelo resurrects: which Ludvig is fratricidal enough? Tunisia by security tips on in october Click on after half term holidays amongst families or other countries most of october half term external links are of a unhcr publication. When it in terms of a half sicilian and men and guiness work and camels in tunis is they had great and north africa. Canaries Morocco Tunisia Algarve Madeira Egypt in Oct. Republic of Tunisia Matrix of the Secondary Education Support Project. There's less rain shadow between October and December and any showers are. A NATIONAL UNIVERSITY FOR TUNISIA. What to Wear When Traveling in Tunisia Tips For Your Tour. Great deals on holidays to Tunisia including last long all inclusive 20212022 holidays Book now afford a low deposit of just 30pp Flight inclusive. Of october half term. Over the legislative reform to tunisia has led tunisia in october term and hence establishing coherence of national parliament either oppose the pluralism, detailed mosaic floors and. Cost of group in Tunisia Prices in Tunisia Updated Feb 2021. Or groups were drawn from them economically, october term holidays are aiming at times and see something to stake out. Is Tunisia safe? Term used for fine in Tunisia's draft constitution ignites. October half of october early days of investment giventhe difficult to act as well previously, terms of five daily. Discover tunisian society might become politically understandable, are more economic perspective, in october term? Where this hot in October 10 balmy destinations CN Traveller. -

Current Catalog

Arte Primitivo Howard S. Rose Gallery, Inc. Fine Pre-Columbian Art, Tribal Art & Classical Antiquities 1. Olmec Miniature Seated Figure 2. Xochipala Tall Standing Figure Mexico. Ca. 1100-700 B.C. 2”H. Olmec culture, Mexico. Ca. 1000 B.C. 11”H. x 3-1/2”W. Private La Jolla collection, acquired from Fine Arts of Ancient Lands, NY. Private FL. collection. Ex. Barry Kernerman, Toronto, ex. Samuel Est. $1,500-$2,000 Closing: Thursday, August 26, 10:00 A.M. Dubiner collection, Tel Aviv, Israel, acquired 1960s. Est. $1,800-$2,500 Closing: Thursday, August 26, 10:01 A.M. 3. Mezcala Large Stone Temple 4. Mezcala Stone Temple Guerrero, Mexico. Ca. 400 B.C. 8-7/8”H. x 6-1/4”W. Guerrero, Mexico. Ca. 400 B.C. 5”H. x 3-3/4”W. Private FL. collection. Ex. Barry Kernerman, Toronto, ex. Samuel Private FL. collection. Ex. Barry Kernerman, Toronto, ex. Samuel Dubiner collection, Tel Aviv, Israel, acquired 1960s. Dubiner collection, Tel Aviv, Israel, acquired 1960s. Est. $800-$1,200 Closing: Thursday, August 26, 10:02 A.M. Est. $900-$1,200 Closing: Thursday, August 26, 10:03 A.M. 5. Tlatilco Figure with Hair Tuft Tlatilco, Mexico. Ca. 1150-550 BC. 5-7/8”H. x 3”W. NYC collection; Ex. Merrin Gallery, 1970s. Est. $600-$900 Closing: Thursday, August 26, 10:04 A.M. 6. Olla with Star Design Chupicuaro, Mexico. Ca. 400-100 B.C. 6-1/2”H. Est. $700-$1,000 Closing: Thursday, August 26, 10:05 A.M. 8. Two Mezcala Pendants 7. -

About Early and Medieval African

CK_4_TH_HG_P087_242.QXD 10/6/05 9:02 AM Page 146 IV. Early and Medieval African Kingdoms Teaching Idea Create an overhead of Instructional What Teachers Need to Know Master 21, The African Continent, and A. Geography of Africa use it to orient students to the physical Background features discussed in this section. Have them use the distance scale to Africa is the second-largest continent. Its shores are the Mediterranean compute distances, for example, the Sea on the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Red Sea and Indian Ocean length and width of the Sahara. to the east, and the Indian Ocean to the south. The area south of the Sahara is Students might be interested to learn often called sub-Saharan Africa and is the focus of Section C, “Medieval that the entire continental United Kingdoms of the Sudan,” (see pp. 149–152). States could fit inside the Sahara. Mediterranean Sea and Red Sea The Red Sea separates Africa from the Arabian Peninsula. Except for the small piece of land north of the Red Sea, Africa does not touch any other land- Name Date mass. Beginning in 1859, a French company dug the Suez Canal through this nar- The African Continent row strip of Egypt between the Mediterranean and the Red Seas. The new route, Study the map. Use it to answer the questions below. completed in 1869, cut 4,000 miles off the trip from western Europe to India. Atlantic and Indian Oceans The Atlantic Ocean borders the African continent on the west. The first explorations by Europeans trying to find a sea route to Asia were along the Atlantic coast of Africa. -

African Studies in China in the 21St Century: a Historiographical Survey1

Brazilian Journal of African Studies e-ISSN 2448-3923 | ISSN 2448-3915 | v.1, n.2, Jul./Dec. 2016 | p.48-88 AFRICAN STUDIES IN CHINA IN THE 21ST CENTURY: A HISTORIOGRAPHICAL SURVEY1 Li Anshan2 Academic studies are always the reflection of reality. With fast development of China-Africa relations, Africanists outside China have showed great interest in China-Africa academic engagement. One of the important aspects is what has been done in China regarding African studies. I once published an article on African study in China and divided it into four phases, i.e., Contacting Africa (before 1900), Sensing Africa (1900-1949), Supporting Africa (1949-1965), Understanding Africa (1966- 1976) and Studying Africa (1977-2000) (Li 2005). Although China’s trade with Africa increased from $10.5 billion in 2000 to 220 billion in 2014, African studies in China did not have the fortune as the trade. However, the dramatic development of the relation has provided Chinese Africanists with new opportunities and challenges. This paper will elaborate what Chinese Africanists have studied in the period of 2000-2015. What subjects are they interested in? What are the achievements and weaknesses? It is divided into four parts, focus and new interests, achievements, young scholars, references and afterthoughts. Focus and New Interests During the past fifteen years, the focus has been mainly on China- 1 This is a revised and supplemented version of three articles (Li Anshan, 2008-2009a-2012c). I tried to cover various works of Chinese Africanists in different fields. As Chair of Chinese Society of African Historical Studies, I would like to thank the members who responded my email accordingly with the information of their own publications. -

Analysing Migration Policy Frames of Tunisian Civil Society Organizations: How Do They Evaluate EU Migration Policies?

Working Papers No. 14, June 2018 Analysing Migration Policy Frames of Tunisian Civil Society Organizations: How Do They Evaluate EU Migration Policies? Emanuela Roman and Ferruccio Pastore This project is founded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Programme for Research and Innovation under grant agreement no 693055. Working Papers No. 14, June 2018 Analysing Migration Policy Frames of Tunisian Civil Society Organizations: How Do They Evaluate EU Migration Policies? Emanuela Roman and Ferruccio Pastore1 Abstract Based on information gathered through extensive fieldwork in Tunisia, this paper analyses how Tunisian civil society actors represent the Mediterranean space, how they frame migration in general and how they frame specific migration-related policy issues and the factors and actors affecting them. The paper further investigates how Tunisian stakeholders evaluate existing policy responses, focusing in particular on EU policies and cooperation initiatives in this field. Finally, the paper outlines possible policy implications, future developments and desirable improvements with regard to EU–Tunisia cooperation in the field of migration. Introduction Migration and mobility represent an ever more vital but highly contentious field of governance in Euro-Mediterranean relations. Euro-Mediterranean cooperation in this policy area has long been characterized by fundamental divergences of views, interests and approaches, not only between the two shores of the Mediterranean, or between (predominantly) sending, transit and receiving countries,