School Desegregation Can Schools Be “Separate but Equal”?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil Rights Movement and the Legacy of Martin Luther

RETURN TO PUBLICATIONS HOMEPAGE The Dream Is Alive, by Gary Puckrein Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: Excerpts from Statements and Speeches Two Centuries of Black Leadership: Biographical Sketches March toward Equality: Significant Moments in the Civil Rights Movement Return to African-American History page. Martin Luther King, Jr. This site is produced and maintained by the U.S. Department of State. Links to other Internet sites should not be construed as an endorsement of the views contained therein. THE DREAM IS ALIVE by Gary Puckrein ● The Dilemma of Slavery ● Emancipation and Segregation ● Origins of a Movement ● Equal Education ● Montgomery, Alabama ● Martin Luther King, Jr. ● The Politics of Nonviolent Protest ● From Birmingham to the March on Washington ● Legislating Civil Rights ● Carrying on the Dream The Dilemma of Slavery In 1776, the Founding Fathers of the United States laid out a compelling vision of a free and democratic society in which individual could claim inherent rights over another. When these men drafted the Declaration of Independence, they included a passage charging King George III with forcing the slave trade on the colonies. The original draft, attributed to Thomas Jefferson, condemned King George for violating the "most sacred rights of life and liberty of a distant people who never offended him." After bitter debate, this clause was taken out of the Declaration at the insistence of Southern states, where slavery was an institution, and some Northern states whose merchant ships carried slaves from Africa to the colonies of the New World. Thus, even before the United States became a nation, the conflict between the dreams of liberty and the realities of 18th-century values was joined. -

Reverend Jesse Jackson

Fulfilling America's "Single Proposition" By Reverend Jesse L. Jackson, Sr. NAACP Address Philadelphia, Pennsylvania July, 14, 2004 What has made America appealing and respected around the world? Is it our $12 trillion Gross Domestic Product and general affluence - the richest nation in history? That has great appeal, but it's not the essence of what makes America great. Is it our military might? After-all, we're the only superpower in the world. Certainly the world is aware of our might, but our military is not so much respected as feared. Is it our diversity, the fact that people from many different nations, religions and races live together in relative peace? That's important, but not our central idea. The Democratic Party Platform - in the "A Strong, Respected America" section - says: "Alone among nations, America was born in pursuit of an idea - that a free people with diverse beliefs could govern themselves in peace. For more than a century, America has spared no effort to defend and promote that idea around the world." Well there's a kernel of truth in there, but, using their words, "just over a century ago" all Americans were not free. The Democratic Party held our grandparents in slavery. So that's selective memory and revisionist history. The "single proposition" that makes America great and appealing around the world was written by Thomas Jefferson on July 4, 1776, in the Declaration of Independence - the rationale for the founding of our nation - that "all men (and women) are created equal." Even though Thomas Jefferson, a slave holder, did not practice or live up to his own words, it's his "single proposition" that America has sought to fulfill ever since. -

![Roy Wilkins Papers [Finding Aid]. Library Of](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5106/roy-wilkins-papers-finding-aid-library-of-725106.webp)

Roy Wilkins Papers [Finding Aid]. Library Of

Roy Wilkins Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 1997 Revised 2010 April Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms002001 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm81075939 Prepared by Allan Teichroew and Paul Ledvina Revised by Allan Teichroew Collection Summary Title: Roy Wilkins Papers Span Dates: 1901-1980 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1932-1980) ID No.: MSS75939 Creator: Wilkins, Roy, 1901-1981 Extent: 28,200 items ; 76 containers ; 30.7 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Civil rights leader and journalist. Correspondence, memoranda, diary, manuscripts of speeches, newspaper columns, and articles, subject files, reports, minutes, committee, board, and administrative material, printed material, and other papers relating primarily to Wilkins's career with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in various positions between 1931 and 1977, especially his service as executive director (1965-1977). Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Carter, Robert L., 1917-2012--Correspondence. Current, Gloster B. (Gloster Bryant), 1913-1997--Correspondence. Du Bois, W. E. B. (William Edward Burghardt), 1868-1963. Evers, Charles, 1922- --Correspondence. Farmer, James, 1920- --Correspondence. Franklin, Chester Arthur, 1880-1955--Correspondence. Hastie, William, 1904-1976--Correspondence. -

Teaching the March on Washington

Nearly a quarter-million people descended on the nation’s capital for the 1963 March on Washington. As the signs on the opposite page remind us, the march was not only for civil rights but also for jobs and freedom. Bottom left: Martin Luther King Jr., who delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech during the historic event, stands with marchers. Bottom right: A. Philip Randolph, the architect of the march, links arms with Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers and the most prominent white labor leader to endorse the march. Teaching the March on Washington O n August 28, 1963, the March on Washington captivated the nation’s attention. Nearly a quarter-million people—African Americans and whites, Christians and Jews, along with those of other races and creeds— gathered in the nation’s capital. They came from across the country to demand equal rights and civil rights, social justice and economic justice, and an end to exploitation and discrimination. After all, the “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom” was the march’s official name, though with the passage of time, “for Jobs and Freedom” has tended to fade. ; The march was the brainchild of longtime labor leader A. PhilipR andolph, and was organized by Bayard RINGER Rustin, a charismatic civil rights activist. Together, they orchestrated the largest nonviolent, mass protest T in American history. It was a day full of songs and speeches, the most famous of which Martin Luther King : AFP/S Jr. delivered in the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial. top 23, 23, GE Last month marked the 50th anniversary of the march. -

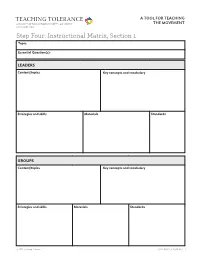

Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Topic

TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Topic: Essential Question(s): LEADERS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards GROUPS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: EVENTS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards HISTORICAL CONTEXT Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: OPPOSITION Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards TACTICS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: CONNECTIONS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 (SAMPLE) Topic: 1963 March on Washington Essential Question(s): How do the events and speeches of the 1963 March on Washington illustrate the characteristics of the civil rights movement as a whole? LEADERS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Martin Luther King Jr., A. -

Civil Rights History Project Interview Completed by the Southern Oral

Civil Rights History Project Interview completed by the Southern Oral History Program under contract to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History & Culture and the Library of Congress, 2013 Interviewee: Cecilia Suyat Marshall Interview Date: June 29, 2013 Location: Falls Church, Virginia Interviewer: Emilye Crosby Videographer: John Bishop Length: 30:49 minutes [Sounds of conversation, laughter, children’s voices, and other activity going on in the church where the interview takes place. The sounds continue in the background throughout the interview.] Emilye Crosby: Ready, John? John Bishop: We’re back on. Emilye Crosby: Okay. What was your awareness or impression of race growing up in Hawaii at that time? Cecilia Suyat Marshall: I really didn’t have any idea at all, because I went to school with different nationalities, Japanese, Filipino, Chinese, and I think there was only one Negro family in the whole section where I was. They didn’t have any children. EC: Um-hmm. Cecilia Suyat Marshall, June 29, 2013 2 CM: And it wasn’t really until I went to New York that I found out about the racial problem. EC: I was going to ask: What was it like to go to New York after—? CM: It was great. I loved it. EC: Yeah? CM: See, my father was still trying to break up my—[laughs] EC: [Laughs] CM: But it’s funny the way things are, because I went to New York and got into Columbia University for a stenographic session. And then, by that time, I got a job. And my father said, “Well, if you love New York, you’ve got to support yourself. -

Mcleod Bethune Papers: the Bethune Foundation Collection Part 2: Correspondence Files, 1914–1955

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier BethuneBethuneMaryMary McLeod PAPERS THE BETHUNE FOUNDATION COLLECTION PART 2: CORRESPONDENCE FILES, 19141955 UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier Mary McLeod Bethune Papers: The Bethune Foundation Collection Part 2: Correspondence Files, 1914–1955 Editorial Adviser Elaine Smith Alabama State University Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide Compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bethune, Mary McLeod, 1875–1955. Mary McLeod Bethune papers [microform] : the Bethune Foundation collection microfilm reels. : 35 mm. — (Black studies research sources) Contents: pt. 1. Writings, diaries, scrapbooks, biographical materials, and files on the National Youth Administration and women’s organizations, 1918–1955. pt. 2. Correspondence Files, 1914–1955. / editorial adviser, Elaine M. Smith: project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. Accompanied by printed guide with title: A guide to the microfilm edition of Mary McLeod Bethune papers. ISBN 1-55655-663-2 1. Bethune, Mary McLeod, 1875–1955—Archives. 2. Afro-American women— Education—Florida—History—Sources. 3. United States. National Youth Administration—History—Sources. 4. National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (U.S.)—History—Sources. 5. National Council of Negro Women— History—Sources. 6. Bethune-Cookman College (Daytona Beach, Fla.)—History— Sources. -

Civil Rights Done Right a Tool for Teaching the Movement TEACHING TOLERANCE

Civil Rights Done Right A Tool for Teaching the Movement TEACHING TOLERANCE Table of Contents Introduction 2 STEP ONE Self Assessment 3 Lesson Inventory 4 Pre-Teaching Reflection 5 STEP TWO The "What" of Teaching the Movement 6 Essential Content Coverage 7 Essential Content Coverage Sample 8 Essential Content Areas 9 Essential Content Checklist 10 Essential Content Suggestions 12 STEP THREE The "How" of Teaching the Movement 14 Implementing the Five Essential Practices 15 Implementing the Five Essential Practices Sample 16 Essential Practices Checklist 17 STEP FOUR Planning for Teaching the Movement 18 Instructional Matrix, Section 1 19 Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Sample 23 Instructional Matrix, Section 2 27 Instructional Matrix, Section 2 Sample 30 STEP FIVE Teaching the Movement 33 Post-Teaching Reflection 34 Quick Reference Guide 35 © 2016 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT // 1 TEACHING TOLERANCE Civil Rights Done Right A Tool for Teaching the Movement Not long ago, Teaching Tolerance issued Teaching the Movement, a report evaluating how well social studies standards in all 50 states support teaching about the modern civil rights movement. Our report showed that few states emphasize the movement or provide classroom support for teaching this history effectively. We followed up these findings by releasingThe March Continues: Five Essential Practices for Teaching the Civil Rights Movement, a set of guiding principles for educators who want to improve upon the simplified King-and-Parks-centered narrative many state standards offer. Those essential practices are: 1. Educate for empowerment. 2. Know how to talk about race. 3. Capture the unseen. 4. Resist telling a simple story. -

NAACP an American Organization, June 1956

HE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF CoLORED PEoPLE is an American organization. Its philos T ophy, its program and its goals derive from the nation's hallowed democratic traditions. From the beginning, the task of the NAACP has been to wipe out racial discrimination and segregation. It has worked always in a legal manner, through the courts and according to federal and state laws and the United States Constitution. It has also sought the enactment of new civil rights laws and the development of a favorable climate of opinion. pledge allegiance to the The Association, as the record plainly shows, has won many battles in the long struggle for first class citizenship for Negro flag of the United States of America Americans. These successes have aroused the anger of those and to the republic for which it who believe in the Jim Crow way of life. The leaders of this outmoded system have declared war on stands; one nation, under God, in- the NAACP because it has spearheaded the fight for equality. They have passed laws, invoked economic sanctions, and re divisible, with liberty and justice sorted to threats, intimidation and violence in their efforts to wreck the NAACP and halt the march of progress. for all. In recent years the defenders of this lost cause have sought to smear the NAACP by falsely linking it with the Communist party. The more reckless white supremacy spokesmen have openly charged that the NAACP is "Communist-dominated" and listed as "subversive." The more cautious have tried to con vict the NAACP of "guilt by association," claiming that cer tain officers and members have, at one time or another, been affiliated with organizations subsequently listed by the United States Attorney General as "subversive." 3 r------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ --- The NAACP position on the Communist party is clear and 2. -

Roy Wilkins Part 7 of 17

-a ., .13: -5-. .14-." _ .-.3 *-. Zi- P_ Q » In I 2 I 1- -:'' _ -- --:77, h_'1'-_ HFwG -1-ans -_'¥"."=",l_1.- "Y. E.-"7"'.-;:__§j"§ -''15- - "- ,;',f.-L _ - r-.-'_,- Q . ' w. 1' ,. @ . _ _. -- - V - _ - - _- . ,'."é-1"-'_'55.1;1 -,_".-_ 33--_j.I;l-gag *.-'=1. "Q:--_'..l': >-'1"t:.'_'r"_.." -"":-- -_'f:5 W - _ '~-- _' 1. ' . -¢._ _ . ' "U"--'------. _- - . _ .....-Y . _~..';.-* _.-I _ ." I I . 1- . .-.-..-»~=-,_-_ -- - -. -._"--7; _,. 4 _'92_,= .1; "'.."'I_-._ . _."..*?L**=.-.-_ _ 1..- -. _ » I - .~ :~- 1 --2*. ~-"- 1 .. .. _.92.*:~-."- . - < -- ._ -T":-- _ . a -. - - - '-- '-.|'_."' _ . _ - _ __ -. , 1. - _ _-- ».- . .- - -_ _-- »_._. - _ _; -______ .'@- -. 92._--'_.- """'92-Q' ' i»*&&1 >.-n¢.|--.1--Ii-- -""""'~ r~?.-."" *"" .* ' _ . 1 - - _ .__ .. _ . .. _ :~+ , _ . - - , an. i bl, '--,,-. _A_'.< _; _ l ' - '_": .. .- .- - , .-I ¢,. Q -2'. ' . I '1 I. I - '."' '3'; u4- - l _, -r92-.-- -. -*5 I 3". ., ._ _ , -§%i@i I3 §§$§@§§ dmL" "Y E --mi. 0 EP2 41964 ww- RADIO "lll.._____ I ff- FBI PoarLann._-= _ 1-01.;PDST nsrsnnnn 9-24-54 JAF _.:@.. to xnzcton ' .. _rnn Poiznnn 151-221 '- * 1? k R0 ILKINS, EXECUTIVESECRETARY, NAACP. -

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement Introduction Research Questions Who comes to mind when considering the Modern Civil Rights Movement (MCRM) during 1954 - 1965? Is it one of the big three personalities: Martin Luther to Consider King Jr., Malcolm X, or Rosa Parks? Or perhaps it is John Lewis, Stokely Who were some of the women Carmichael, James Baldwin, Thurgood Marshall, Ralph Abernathy, or Medgar leaders of the Modern Civil Evers. What about the names of Septima Poinsette Clark, Ella Baker, Diane Rights Movement in your local town, city or state? Nash, Daisy Bates, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ruby Bridges, or Claudette Colvin? What makes the two groups different? Why might the first group be more familiar than What were the expected gender the latter? A brief look at one of the most visible events during the MCRM, the roles in 1950s - 1960s America? March on Washington, can help shed light on this question. Did these roles vary in different racial and ethnic communities? How would these gender roles On August 28, 1963, over 250,000 men, women, and children of various classes, effect the MCRM? ethnicities, backgrounds, and religions beliefs journeyed to Washington D.C. to march for civil rights. The goals of the March included a push for a Who were the "Big Six" of the comprehensive civil rights bill, ending segregation in public schools, protecting MCRM? What were their voting rights, and protecting employment discrimination. The March produced individual views toward women one of the most iconic speeches of the MCRM, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a in the movement? Dream" speech, and helped paved the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and How were the ideas of gender the Voting Rights Act of 1965. -

The Civil Rights Movement

Star Lecture with Professor Lou Kushnick GLOSSARY The glossary is divided into the following categories: Laws and Acts, Events and Locations, Terminology and Events and Locations. LAWS ANDS ACTS 13TH AMENDMENT Adopted in 1864. Abolished slavery and involuntary servitude in all States. Adopted in 1868. Allows Blacks to be determined to be United States Citizens. Overturned previous ruling in Dred 14TH AMENDMENT Scott v. Sandford of 1857. Adopted in 1970. Bans all levels of government in the United States from denying a citizen the right to vote based 15TH AMENDMENT on that citizen's "race, colour, or previous condition of servitude" BROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION A landmark Supreme Court decision in 1954 that declared segregated education as unconstitutional. This victory was a launchpad for other challenges to de jure segregation in other field of public life – including transportation. Like many challenges to segregation, Brown was a case presented by a collection of individuals in a class action lawsuit – one of whom was Oliver Brown, who was unhappy that his child had travel a number of block to attend a Black school when a White school was much nearer. By the time the case reached the Supreme Court it actually encompassed a number of cases brought by parents against School Boards. The funds for the legal challenges were provided by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). This wide-reaching Act prohibited racial and gender discrimination in public services and areas. It was originally created by President Kennedy, but was signed into existence after his assassination by President Johnson.