Trade Books' Historical Representation of Eleanor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

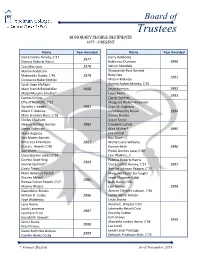

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

American Heritage Day

American Heritage Day DEAR PARENTS, Each year the elementary school students at Valley Christian Academy prepare a speech depicting the life of a great American man or woman. The speech is written in the first person and should include the character’s birth, death, and major accomplishments. Parents should feel free to help their children write these speeches. A good way to write the speech is to find a child’s biography and follow the story line as you construct the speech. This will make for a more interesting speech rather than a mere recitation of facts from the encyclopedia. Students will be awarded extra points for including spiritual application in their speeches. Please adhere to the following time limits. K-1 Speeches must be 1-3 minutes in length with a minimum of 175 words. 2-3 Speeches must be 2-5 minutes in length with a minimum of 350 words. 4-6 Speeches must be 3-10 minutes in length with a minimum of 525 words. Students will give their speeches in class. They should be sure to have their speeches memorized well enough so they do not need any prompts. Please be aware that students who need frequent prompting will receive a low grade. Also, any student with a speech that doesn’t meet the minimum requirement will receive a “D” or “F.” Students must portray a different character each year. One of the goals of this assignment is to help our children learn about different men and women who have made America great. Help your child choose characters from whom they can learn much. -

Civil Rights Movement and the Legacy of Martin Luther

RETURN TO PUBLICATIONS HOMEPAGE The Dream Is Alive, by Gary Puckrein Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: Excerpts from Statements and Speeches Two Centuries of Black Leadership: Biographical Sketches March toward Equality: Significant Moments in the Civil Rights Movement Return to African-American History page. Martin Luther King, Jr. This site is produced and maintained by the U.S. Department of State. Links to other Internet sites should not be construed as an endorsement of the views contained therein. THE DREAM IS ALIVE by Gary Puckrein ● The Dilemma of Slavery ● Emancipation and Segregation ● Origins of a Movement ● Equal Education ● Montgomery, Alabama ● Martin Luther King, Jr. ● The Politics of Nonviolent Protest ● From Birmingham to the March on Washington ● Legislating Civil Rights ● Carrying on the Dream The Dilemma of Slavery In 1776, the Founding Fathers of the United States laid out a compelling vision of a free and democratic society in which individual could claim inherent rights over another. When these men drafted the Declaration of Independence, they included a passage charging King George III with forcing the slave trade on the colonies. The original draft, attributed to Thomas Jefferson, condemned King George for violating the "most sacred rights of life and liberty of a distant people who never offended him." After bitter debate, this clause was taken out of the Declaration at the insistence of Southern states, where slavery was an institution, and some Northern states whose merchant ships carried slaves from Africa to the colonies of the New World. Thus, even before the United States became a nation, the conflict between the dreams of liberty and the realities of 18th-century values was joined. -

Children of Stuggle Learning Guide

Library of Congress LIVE & The Smithsonian Associates Discovery Theater present: Children of Struggle LEARNING GUIDE: ON EXHIBIT AT THE T Program Goals LIBRARY OF CONGRESS: T Read More About It! Brown v. Board of Education, opening May T Teachers Resources 13, 2004, on view through November T Ernest Green, Ruby Bridges, 2004. Contact Susan Mordan, (202) Claudette Colvin 707-9203, for Teacher Institutes and T Upcoming Programs school tours. Program Goals About The Co-Sponsors: Students will learn about the Civil Rights The Library of Congress is the largest Movement through the experiences of three library in the world, with more than 120 young people, Ruby Bridges, Claudette million items on approximately 530 miles of Colvin, and Ernest Green. They will be bookshelves. The collections include more encouraged to find ways in their own lives to than 18 million books, 2.5 million recordings, stand up to inequality. 12 million photographs, 4.5 million maps, and 54 million manuscripts. Founded in 1800, and Education Standards: the oldest federal cultural institution in the LANGUAGE ARTS (National Council of nation, it is the research arm of the United Teachers of English) States Congress and is recognized as the Standard 8 - Students use a variety of national library of the United States. technological and information resources to gather and synthesize information and to Library of Congress LIVE! offers a variety create and communicate knowledge. of program throughout the school year at no charge to educational audiences. Combining THEATER (Consortium of National Arts the vast historical treasures from the Library's Education Associations) collections with music, dance and dialogue. -

February 2007 AAUW-Illinois by Barbara Joan Zeitz

CountHerHistory February 2007 AAUW-Illinois by Barbara Joan Zeitz Civil Rights Women: Seventy-three years predating Rosa Parks, a refined teacher sat in the first- class ladies’ car on a train in Tennessee. When told to move to the smoker for niggers, she politely refused. She had a first-class ticket, was a lady, and planned to stay. Dragged to the dirty smoker as white passengers cheered, she got off at the next stop. Ida B. Wells was well within her rights. The Civil Rights Act of 1875 banned discrimination on public transportation. Wells filed a law suit and won. She sued in a repeat situation, won, and inspired others. Her disclosures about lynching began the nation’s anti-lynching campaign. The NAACP began as an interracial organization in 1908 when Mary Ovington, a white woman, hosted a dinner in New York organized and funded by whites. Ovington saw that over a third in positions were women, one was Ida B. Wells. The NAACP ceased being interracial in the 1930’s, excluding Ovington from her civil rights work. Pauli Murray attempted to break the color line in education at the University of North Carolina Law School in 1938, but was denied admission. As a Howard University Law School student in Washington, D. C., she organized a cafeteria sit-in. After four hours of orderly protest, the demonstrators were served. Civil rights were gained. But in 1944 people did not talk about this. The press ignored the story. Those courageous young blacks sitting-in at lunch counters in the 1960’s were ahead of their time. -

Reverend Jesse Jackson

Fulfilling America's "Single Proposition" By Reverend Jesse L. Jackson, Sr. NAACP Address Philadelphia, Pennsylvania July, 14, 2004 What has made America appealing and respected around the world? Is it our $12 trillion Gross Domestic Product and general affluence - the richest nation in history? That has great appeal, but it's not the essence of what makes America great. Is it our military might? After-all, we're the only superpower in the world. Certainly the world is aware of our might, but our military is not so much respected as feared. Is it our diversity, the fact that people from many different nations, religions and races live together in relative peace? That's important, but not our central idea. The Democratic Party Platform - in the "A Strong, Respected America" section - says: "Alone among nations, America was born in pursuit of an idea - that a free people with diverse beliefs could govern themselves in peace. For more than a century, America has spared no effort to defend and promote that idea around the world." Well there's a kernel of truth in there, but, using their words, "just over a century ago" all Americans were not free. The Democratic Party held our grandparents in slavery. So that's selective memory and revisionist history. The "single proposition" that makes America great and appealing around the world was written by Thomas Jefferson on July 4, 1776, in the Declaration of Independence - the rationale for the founding of our nation - that "all men (and women) are created equal." Even though Thomas Jefferson, a slave holder, did not practice or live up to his own words, it's his "single proposition" that America has sought to fulfill ever since. -

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement Introduction Research Questions Who comes to mind when considering the Modern Civil Rights Movement (MCRM) during 1954 - 1965? Is it one of the big three personalities: Martin Luther to Consider King Jr., Malcolm X, or Rosa Parks? Or perhaps it is John Lewis, Stokely Who were some of the women Carmichael, James Baldwin, Thurgood Marshall, Ralph Abernathy, or Medgar leaders of the Modern Civil Evers. What about the names of Septima Poinsette Clark, Ella Baker, Diane Rights Movement in your local town, city or state? Nash, Daisy Bates, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ruby Bridges, or Claudette Colvin? What makes the two groups different? Why might the first group be more familiar than What were the expected gender the latter? A brief look at one of the most visible events during the MCRM, the roles in 1950s - 1960s America? March on Washington, can help shed light on this question. Did these roles vary in different racial and ethnic communities? How would these gender roles On August 28, 1963, over 250,000 men, women, and children of various classes, effect the MCRM? ethnicities, backgrounds, and religions beliefs journeyed to Washington D.C. to march for civil rights. The goals of the March included a push for a Who were the "Big Six" of the comprehensive civil rights bill, ending segregation in public schools, protecting MCRM? What were their voting rights, and protecting employment discrimination. The March produced one individual views toward women of the most iconic speeches of the MCRM, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a in the movement? Dream" speech, and helped paved the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and How were the ideas of gender the Voting Rights Act of 1965. -

A Case Study of Alabama State College Laboratory High School in Historical Context, 1920-1960

A “Laboratory of Learning”: A Case Study of Alabama State College Laboratory High School in Historical Context, 1920-1960 Sharon G. Pierson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Sharon G. Pierson All rights reserved ABSTRACT A “Laboratory of Learning”: A Case Study of Alabama State College Laboratory High School in Historical Context, 1920-1960 Sharon G. Pierson In the first half of the twentieth century in the segregated South, Black laboratory schools began as “model,” “practice,” or “demonstration” schools that were at the heart of teacher training institutions at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Central to the core program, they were originally designed to develop college-ready students, demonstrate effective teaching practices, and provide practical application for student teachers. As part of a higher educational institution and under the supervision of a college or university president, a number of these schools evolved to “laboratory” high schools, playing a role in the development of African American education beyond their own local communities. As laboratories for learning, experimentation, and research, they participated in major cooperative studies and hosted workshops. They not only educated the pupils of the lab school and the student teachers from the institution, but also welcomed visitors from other high schools and colleges with a charge to influence Black education. A case study of Alabama State College Laboratory School, 1920-1960, demonstrates the evolution of a lab high school as part of the core program at an HBCU and its distinctive characteristics of high graduation and college enrollment rates, well-educated teaching staff, and a comprehensive liberal arts curriculum. -

WGC Library Catalogue

Book Title Author (Last name, FirstAuthor name) Category Secondary Category Status Daughters of the Dreaming Bell, Diane Diane Bell Anthropology top shelf For Their Triumph and For Their Tears Bernstein, Hilda Hilda Bernstein Anthropology top shelf Women of the Shadows: The Wives and Mothers of Southern Italy Comelisen, Ann Ann Comelisen Anthropology top shelf Women of Deh Koh Fredi, Erika Erika Fredi Anthropology top shelf Women and the Anscestors: Black Carib Kinship and Ritual Kerns, Virginia Virginia Kerns Anthropology top shelf Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies Mead, Margaret Margaret Mead Anthropology top shelf Murphy, Yolanda & Women of the Forest Robert Yolanda Murphy & Robert Murphy Anthropology top shelf Woman's Consciousness, Man's World Rowbotham, Sheila Anthropology top shelf Exposures: Womem and Their Art Brown, Betty Ann & Raven,Betty Arlene Ann Brown and Arlene Raven Art top shelf Crafting with Feminism Burton, Bonnie Bonnie Burton Art top shelf Feminist Icon Cross-Stitch Fleiss, Anna and Mancuso,Anna Lauren Fleiss and Lauren Mancuso Art Reel to Real: Race, Class, and Sex at the Movies hooks, bell bell hooks Art Sociology top shelf Displaced Allergies: Post-Revolutionary Iranian Cinema Mottahedeh, Negar Negar Mottahedeh Art top shelf Representing the Unrepresentable: Historical Images of National Reform from the Qajars Mottahedeh, Negar Negar Mottahedeh Art Middle Eastern Studies top shelf Sex, Art, and American Culture Paglia, Camile Camille Paglia Art top shelf Women Artists: Recognition and Reappraisal -

![Roy Wilkins Papers [Finding Aid]. Library Of](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5106/roy-wilkins-papers-finding-aid-library-of-725106.webp)

Roy Wilkins Papers [Finding Aid]. Library Of

Roy Wilkins Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 1997 Revised 2010 April Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms002001 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm81075939 Prepared by Allan Teichroew and Paul Ledvina Revised by Allan Teichroew Collection Summary Title: Roy Wilkins Papers Span Dates: 1901-1980 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1932-1980) ID No.: MSS75939 Creator: Wilkins, Roy, 1901-1981 Extent: 28,200 items ; 76 containers ; 30.7 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Civil rights leader and journalist. Correspondence, memoranda, diary, manuscripts of speeches, newspaper columns, and articles, subject files, reports, minutes, committee, board, and administrative material, printed material, and other papers relating primarily to Wilkins's career with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in various positions between 1931 and 1977, especially his service as executive director (1965-1977). Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Carter, Robert L., 1917-2012--Correspondence. Current, Gloster B. (Gloster Bryant), 1913-1997--Correspondence. Du Bois, W. E. B. (William Edward Burghardt), 1868-1963. Evers, Charles, 1922- --Correspondence. Farmer, James, 1920- --Correspondence. Franklin, Chester Arthur, 1880-1955--Correspondence. Hastie, William, 1904-1976--Correspondence. -

Daybreak of Freedom

Daybreak of Freedom . Daubreak of The University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill and London Freedom The Montgomery Bus Boycott Edited by Stewart Burns © 1997 The University of North Carolina Press. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Daybreak of freedom : the Montgomery bus boycott / edited by Stewart Burns, p cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-8078-2360-0 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8078-4661-9 (pbk.: alk. paper) i. Montgomery (Ala.)—Race relations—Sources. 2. Segregation in transportation—Alabama— Montgomery—History—20th century—Sources. 3. Afro-Americans—Civil rights—Alabama- Montgomery—History—2oth century—Sources. I. Title. F334-M79N39 *997 97~79°9 3O5.8'oo976i47—dc2i CIP 01 oo 99 98 97 54321 THIS BOOK WAS DIGITALLY MANUFACTURED. For Claudette Colvin, Jo Ann Robinson, Virginia Foster Durr, and all the other courageous women and men who made democracy come alive in the Cradle of the Confederacy This page intentionally left blank We are here in a general sense because first and foremost we are American citizens, and we are determined to apply our citizenship to the fullness of its meaning. We are here also because of our love for democracy, because of our deep-seated belief that democracy transformed from thin paper to thick action is the greatest form of government on earth. And you know, my friends, there comes a time when people get tired of being trampled over by the iron feet of oppression. -

The Legacy of Marian Anderson

Date: Thursday, April 4th, 2013, 12:30pm Place: Hillwood Commons Lecture Hall Speaker: Marc Courtade newyorker.com Marian Anderson was one of the most celebrated singers of the twentieth century. She became an important figure in the struggle for black artists to overcome racial prejudice in the United States during the mid-twentieth century. In 1939, the Daughters of the American Revolution refused permission for Anderson to sing to an integrated audience in Constitution Hall. Instead, with the aid of Eleanor Roosevelt, Anderson performed a critically acclaimed open-air concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday, April 9, 1939. She sang before a crowd of more than 75,000 people and a radio audience in the millions. In 1955, Anderson broke the color barrier by becoming the first African-American to perform with the Metropolitan Opera. In 1958 she was officially designated delegate to the United Nations, a formalization of her role as "goodwill ambassador" of the U.S., and in 1972 she was awarded the UN Peace Prize. Anderson may have been a reluctant participant in the civil rights movement, but greatness was thrust upon her. A generation of African-American singers is indebted to her for blazing the trail towards equality. About the Speaker... Marc Courtade is Business Manager for Tilles Center for the Performing Arts at Long Island University, and Producer and Artistic Director of Performance Plus!, a pre-performance lecture series. He is a frequent lecturer for the Hutton House Lectures, specializing in Musicals and Opera courses, and Adjunct Professor in the Arts Management curriculum.