AJ Muste's Theology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LETTER from the PRESIDENT, SANDY GOLDSTEIN Alive@Five As an Economic Engine for the Downtown

61080_SD_NL.qxp:0 11/9/11 2:19 PM Page 1 N UMBER 43 • FALL 2011 LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT, SANDY GOLDSTEIN Alive@Five as an Economic Engine for the Downtown Now that we are several months removed from our summer events, it’s According to Todd Kosakowski whose illuminating to evaluate them through the very important prism of company owns Black Bear Saloon, Downtown economic development; after all, economic development is Hula Hanks Island Bar & Grille and what Downtown event production is all about. 84 Park and Mike Marchetti, the owner The value of the performing arts in spurring the economy has long been of Columbus Park Trattoria, most known. According to the national research organization, Americans for Columbus Park area restaurants do the Arts, movie, theatre and concert-goers spend an average of $23 for an average of seven times the amount every dollar spent on tickets. This is a national average, which is much of business on Alive@Five Thursdays lower than what is spent in Fairfield County. However, using the research than done on other Thursday nights. This amounts to a 600% jump in organization’s conservative formula, the 75,000 patrons who attended the The streets & outdoor patios alike seven Alive@Five concerts this season, spent an estimated $1,725,000 to dine somewhere in the city. business! Let’s look at these numbers another way. If a restaurant does were packed all season at Alive@Five The latter number tells only part of the story. Delving deeper into the facts of producing the $4,000 on a normal Thursday, then on Alive@Five series, a compelling picture of economic development success emerges. -

Biu Withers by Rob Bowman He Was the Leading Figure in the Nascent Black Singer-Songwriter Movement of the Early 1970S

PERFORMERS BiU Withers By Rob Bowman He was the leading figure in the nascent black singer-songwriter movement of the early 1970s. BILL WITHERS WAS SIMPLY NOT BORN TO PLAY THE record industry game. His oft-repeated descriptor for A&R men is “antagonistic and redundant.” Not surprisingly, most A&R men at Columbia Records, the label he recorded for beginning in 1975, considered him “difficult.” Yet when given the freedom to follow his muse, Withers wrote, sang, and in many cases produced some of our most enduring classics, including “Ain’t No Sunshine,” “Lean on Me,” “Use Me,” “Lovely Day,” “Grandma’s Hands,” and “Who Is He (and What Is He to You).” ^ “Not a lot of people got me,” Withers recently mused. “Here I was, this black guy playing an acoustic guitar, and I wasn’t playing the gut-bucket blues. People had a certain slot that they expected you to fit in to.” ^ Withers’ story is about as improb able as it could get. His first hit, “Ain’t No Sunshine,” recorded in 1971 when he was 33, broke nearly every pop music rule. Instead of writing words for a bridge, Withers audaciously repeated “I know” twenty-six times in a row. Moreover, the two-minute song had no introduction and was released as a throwaway B-side. Produced by Stax alumni Booker T. Jones for Sussex Records, the single’s struc ture, sound, and sentiment were completely unprecedented and pos sessed a melody and lyric that tapped into the Zeitgeist of the era. Like much of Withers’ work, it would ultimately prove to be timeless. -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

February 2007 AAUW-Illinois by Barbara Joan Zeitz

CountHerHistory February 2007 AAUW-Illinois by Barbara Joan Zeitz Civil Rights Women: Seventy-three years predating Rosa Parks, a refined teacher sat in the first- class ladies’ car on a train in Tennessee. When told to move to the smoker for niggers, she politely refused. She had a first-class ticket, was a lady, and planned to stay. Dragged to the dirty smoker as white passengers cheered, she got off at the next stop. Ida B. Wells was well within her rights. The Civil Rights Act of 1875 banned discrimination on public transportation. Wells filed a law suit and won. She sued in a repeat situation, won, and inspired others. Her disclosures about lynching began the nation’s anti-lynching campaign. The NAACP began as an interracial organization in 1908 when Mary Ovington, a white woman, hosted a dinner in New York organized and funded by whites. Ovington saw that over a third in positions were women, one was Ida B. Wells. The NAACP ceased being interracial in the 1930’s, excluding Ovington from her civil rights work. Pauli Murray attempted to break the color line in education at the University of North Carolina Law School in 1938, but was denied admission. As a Howard University Law School student in Washington, D. C., she organized a cafeteria sit-in. After four hours of orderly protest, the demonstrators were served. Civil rights were gained. But in 1944 people did not talk about this. The press ignored the story. Those courageous young blacks sitting-in at lunch counters in the 1960’s were ahead of their time. -

Peace and War

Peace and War Christian Reflection A SERIES IN FAITH AND ETHICS BAYLOR UNIVERSITY GENERAL EDITOR Robert B. Kruschwitz ART EDITOR Heidi J. Hornik REVIEW EDITOR Norman Wirzba PRODUCTION ASSISTANT Julie Bolin DESIGNER Eric Yarbrough PUBLISHER The Center for Christian Ethics Baylor University One Bear Place #97361 Waco, TX 76798-7361 PHONE (254) 710-3774 TOLL-FREE (USA) (866) 298-2325 W E B S I T E www.ChristianEthics.ws E-MAIL [email protected] All Scripture is used by permission, all rights reserved, and unless otherwise indicated is from New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. ISSN 1535-8585 Christian Reflection is the ideal resource for discipleship training in the church. Multiple copies are obtainable for group study at $2.50 per copy. Worship aids and lesson materials that enrich personal or group study are available free on the website. Christian Reflection is published quarterly by The Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University. Contributors express their considered opinions in a responsible manner. The views expressed are not official views of The Center for Christian Ethics or of Baylor University. The Center expresses its thanks to individuals, churches, and organizations, including the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, who provided financial support for this publication. © 2004 The Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University All rights reserved Contents Introduction 8 Robert B. Kruschwitz War in the Old Testament 11 John A. Wood The War of the Lamb 18 Harry O. Maier Terrorist Enemies and Just War 27 William T. -

A Case Study of Alabama State College Laboratory High School in Historical Context, 1920-1960

A “Laboratory of Learning”: A Case Study of Alabama State College Laboratory High School in Historical Context, 1920-1960 Sharon G. Pierson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Sharon G. Pierson All rights reserved ABSTRACT A “Laboratory of Learning”: A Case Study of Alabama State College Laboratory High School in Historical Context, 1920-1960 Sharon G. Pierson In the first half of the twentieth century in the segregated South, Black laboratory schools began as “model,” “practice,” or “demonstration” schools that were at the heart of teacher training institutions at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Central to the core program, they were originally designed to develop college-ready students, demonstrate effective teaching practices, and provide practical application for student teachers. As part of a higher educational institution and under the supervision of a college or university president, a number of these schools evolved to “laboratory” high schools, playing a role in the development of African American education beyond their own local communities. As laboratories for learning, experimentation, and research, they participated in major cooperative studies and hosted workshops. They not only educated the pupils of the lab school and the student teachers from the institution, but also welcomed visitors from other high schools and colleges with a charge to influence Black education. A case study of Alabama State College Laboratory School, 1920-1960, demonstrates the evolution of a lab high school as part of the core program at an HBCU and its distinctive characteristics of high graduation and college enrollment rates, well-educated teaching staff, and a comprehensive liberal arts curriculum. -

Daybreak of Freedom

Daybreak of Freedom . Daubreak of The University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill and London Freedom The Montgomery Bus Boycott Edited by Stewart Burns © 1997 The University of North Carolina Press. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Daybreak of freedom : the Montgomery bus boycott / edited by Stewart Burns, p cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-8078-2360-0 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8078-4661-9 (pbk.: alk. paper) i. Montgomery (Ala.)—Race relations—Sources. 2. Segregation in transportation—Alabama— Montgomery—History—20th century—Sources. 3. Afro-Americans—Civil rights—Alabama- Montgomery—History—2oth century—Sources. I. Title. F334-M79N39 *997 97~79°9 3O5.8'oo976i47—dc2i CIP 01 oo 99 98 97 54321 THIS BOOK WAS DIGITALLY MANUFACTURED. For Claudette Colvin, Jo Ann Robinson, Virginia Foster Durr, and all the other courageous women and men who made democracy come alive in the Cradle of the Confederacy This page intentionally left blank We are here in a general sense because first and foremost we are American citizens, and we are determined to apply our citizenship to the fullness of its meaning. We are here also because of our love for democracy, because of our deep-seated belief that democracy transformed from thin paper to thick action is the greatest form of government on earth. And you know, my friends, there comes a time when people get tired of being trampled over by the iron feet of oppression. -

Exiles in Their Own Land: Japanese Protestant Mission History and Theory in Conversation with Practical Theology

1 YALE DIVINITY SCHOOL LIBRARY Occasional Publication No. 25 Exiles in their Own Land: Japanese Protestant Mission History and Theory in Conversation with Practical Theology by Thomas John Hastings NEW HAVEN, CONNECTICUT March, 2018 2 The Occasional Publications of the Yale Divinity School Library are sponsored by The George Edward and Olivia Hotchkiss Day Associates. This Day Associates Lecture was delivered by Thomas John Hastings on June 30, 2017, during the annual meeting of the Yale-Edinburgh Group on the History of the Missionary Movement and World Christianity. The theme of the 2017 meeting was “Migration, Exile, and Pilgrimage in the History of Missions and World Christianity.” Thomas John Hastings is Executive Director of the Overseas Ministries Study Center in New Haven, Connecticut. Dr. Hastings is also Editor of the International Bulletin of Mission Research. He has published two books Seeing All Things Whole: The Scientific Mysticism and Art of Kagawa Toyohiko, 1888-1960 (Wipf & Stock, Pickwick, 2015) and Practical Theology and the One Body of Christ: Toward a Missional-Ecumenical Model (Eerdmans, 2007), as well as numerous book chapters, journal articles, and translations in both English and Japanese. 3 SLIDE 1 Introduction: In 1988, Carol and I were appointed as a PC (USA) Mission Co-workers in Kanazawa, Japan. I was Lecturer at Hokuriku Gakuin University, a Kindergarten-college “mission school” founded by an American Presbyterian named Mary Hesser in 1885 as Kanazawa’s first educational institution for girls and young women. Kanazawa is located on the Japan Sea where the Jodo-Shinshu sect of Buddhism is the dominant religious affiliation of most families. -

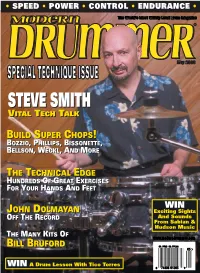

Steve Smith Steve Smith

• SPEED • POWER • CONTROL • ENDURANCE • SPECIAL TECHNIQUE ISSUE STEVESTEVE SMITHSMITH VVITALITAL TTECHECH TTALKALK BBUILDUILD SSUPERUPER CCHOPSHOPS!! BBOZZIOOZZIO,, PPHILLIPSHILLIPS,, BBISSONETTEISSONETTE,, BBELLSONELLSON,, WWECKLECKL,, AANDND MMOREORE TTHEHE TTECHNICALECHNICAL EEDGEDGE HHUNDREDSUNDREDS OOFF GGREATREAT EEXERCISESXERCISES FFOROR YYOUROUR HHANDSANDS AANDND FFEETEET WIN JJOHNOHN DDOLMAYANOLMAYAN Exciting Sights OOFFFF TTHEHE RRECORDECORD And Sounds From Sabian & Hudson Music TTHEHE MMANYANY KKITSITS OOFF BBILLILL BBRUFORDRUFORD $4.99US $6.99CAN 05 WIN A Drum Lesson With Tico Torres 0 74808 01203 9 Contents ContentsVolume 27, Number 5 Cover photo by Alex Solca STEVE SMITH You can’t expect to be a future drum star if you haven’t studied the past. As a self-proclaimed “US ethnic drummer,” Steve Smith has made it his life’s work to explore the uniquely American drumset— and the way it has shaped our music. by Bill Milkowski 38 Alex Solca BUILDING SUPER CHOPS 54 UPDATE 24 There’s more than one way to look at technique. Just ask Terry Bozzio, Thomas Lang, Kenny Aronoff, Bill Bruford, Dave Weckl, Paul Doucette Gregg Bissonette, Tommy Aldridge, Mike Mangini, Louie Bellson, of Matchbox Twenty Horacio Hernandez, Simon Phillips, David Garibaldi, Virgil Donati, and Carl Palmer. Gavin Harrison by Mike Haid of Porcupine Tree George Rebelo of Hot Water Music THE TECHNICAL EDGE 73 Duduka Da Fonseca An unprecedented gathering of serious chops-increasing exercises, samba sensation MD’s exclusive Technical Edge feature aims to do no less than make you a significantly better drummer. Work out your hands, feet, and around-the-drums chops like you’ve never worked ’em before. A DIFFERENT VIEW 126 TOM SCOTT You’d need a strongman just to lift his com- plete résumé—that’s how invaluable top musicians have found saxophonist Tom Scott’s playing over the past three decades. -

Christian Pacifism and Just-War Tenets: How Do They Diverge?

Theological Studies 47 (1986) CHRISTIAN PACIFISM AND JUST-WAR TENETS: HOW DO THEY DIVERGE? RICHARD B. MILLER Indiana University ECENT STUDIES in Christian ethics have uncovered a "point of R convergence" between pacifist convictions and just-war tenets. Al though it is easy to assume that just-war ideas and pacifism are wholly incompatible approaches to the morality of warfare, James Childress argues that pacifists and just-war theorists actually share a common starting point: a moral presumption against the use of force. Childress uses W. D. Ross's language of prima-facie duties to show how pacifism and just-war thought converge. The duty not to kill or injure others (nonmaleficence) is a duty within each approach. For the pacifist, non- maleficence is an absolute duty admitting of no exceptions. For just-war theorists, nonmaleficence is a prima-facie duty, that is, a duty that is usually binding but may be overridden in exceptional circumstances— particularly when innocent life and human rights are at stake. Prima- facie duties are not absolute, but place the burden of proof on those who wish to override them when they conflict with other duties, "in virtue of the totality of... ethically relevant circumstances."1 War poses just those exceptional circumstances in which the duty of nonmaleficence may be overridden. In this way Childress both highlights the point of contact between pacifism and just-war tenets and reconstructs the essential logic of the jus ad bellum. To override a prima-facie duty, however, is not to abandon it. Such duties continue to function in the situation or in the subsequent course of action. -

A Legacy of Cooperation

A Legacy of Cooperation NASCO INSTITUTE • NOVEMBER 2-4, 2018 • ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN Welcome to NASCO Institute Welcome to the 50th Anniversary NASCO Cooperative Education and Training Institute! This gathering would not be possible without the board of directors, presenters, volunteers, and, of course, you! We hope that before you return home you will try something new, expand your cooperative skills toolbox, make lasting connections with fellow co-opers, and use this year’s conference theme to explore the ways that you and your cooperatives are connected to a resilient, global movement. Finally, we value your input and participation in NASCO’s governance. We encourage you to dive in and take part in caucuses (Friday and Saturday evenings), run for a seat on the board as Active Member Representative (during the Saturday night Banquet), attend the Annual General Meeting (Sunday during course blocks 4 and 5), and commit to taking action to keep momentum rolling through the year. Sincerely, Team NASCO Liz Anderson Ratih Sutrisno Brel Hutton-Okpalaeke Director of Education Director of Community Director of Development Engagement Services Katherine Jennings Daniel Miller Director of Operations Director of Properties NASCO BOARD OF DIRECTORS Christopher Bell Mer Kammerling Sydney Burke Matthew Kemper Leonie Cesvette Camryn Kessler Robert Cook Tristan Laing Nick Coquillard Nola Warner Alex Green Lana Wong Topaz Hooper Kiyomi de Zoysa 1 NASCO Cooperative Education and Training Institute 2 Table of contents Welcome ......................................................................................................................................................... -

Reimagining the Postwar International Order: the World Federalism of Ozaki Yukio and Kagawa Toyohiko Konrad M

Reimagining the Postwar International Order: The World Federalism of Ozaki Yukio and Kagawa Toyohiko Konrad M. Lawson The years of transition from the League of Nations to the United Nations were accompanied by a creative surge of transnational idealism. The horrors of the Second World War and the possibility of global destruction at the hands of nuclear weapons generated enthusiastic calls for a world government that might significantly restrain the ability of independent political entities to wage war against each other and that could serve as a platform for legislation enforceable as world law.1 Drawing inspiration from a long history of political thought from Kant to Kang Youwei, almost all of these plans proposed variations on a federal system that preserved a layer of national, and indeed imperial, government, while dissolving forever the inviolability of sovereignty. Above nations and empires in the imagined new order would exist a global federal body that, depending on the scheme, would possess significant powers of taxation, a monopoly on military coercion–or at least sole possession of nuclear weapons–and powers of legislation that could both bind nations and empower individuals. In her sweeping history of twentieth-century internationalism, Glenda Sluga considers various schemes for world federalism as part of the “apogee of internationalism” of the 1940s; the transitional period during which these plans occupied a space simultaneously with the development of ideas of world citizenship seeking to renegotiate the traditional subordination of the individual to the state. Even if a world federation did not call for the abolition of nation-states, in both these cases, Sluga argues, the goal of any eventual “world” solution would be called for in the name of people’s interests.2 These interests, in the name of the people, or which elevated the individual, would continue to emerge in the development of the United Nations charter and its affiliated institutions, but the new inter-national body abandoned many of the ambitions of earlier federalist visions.