Peace and War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

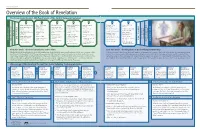

Overview of the Book of Revelation the Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’S Temporal Existence)

NEW TESTAMENT Overview of the Book of Revelation The Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’s Temporal Existence) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Adam’s ministry began City of Enoch was Abraham’s ministry Israel was divided into John the Baptist’s Renaissance and Destruction of the translated two kingdoms ministry Reformation wicked Wickedness began to Isaac, Jacob, and spread Noah’s ministry twelve tribes of Israel Isaiah’s ministry Christ’s ministry Industrial Revolution Christ comes to reign as King of kings Repentance was Great Flood— Israel’s bondage in Ten tribes were taken Church was Joseph Smith’s ministry taught by prophets and mankind began Egypt captive established Earth receives Restored Church patriarchs again paradisiacal glory Moses’s ministry Judah was taken The Savior’s atoning becomes global CREATION Adam gathered and Tower of Babel captive, and temple sacrifice Satan is bound Conquest of land of Saints prepare for Christ EARTH’S DAY OF DAY EARTH’S blessed his children was destroyed OF DAY EARTH’S PROBATION ENDS PROBATION PROBATION ENDS PROBATION ETERNAL REWARD FALL OF ADAM FALL Jaredites traveled to Canaan Gospel was taken to Millennial era of peace ETERNAL REWARD ETERNITIES PAST Great calamities Great calamities FINAL JUDGMENT FINAL JUDGMENT PREMORTAL EXISTENCE PREMORTAL Adam died promised land Jews returned to the Gentiles and love and love ETERNITIES FUTURE Israelites began to ETERNITIES FUTURE ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Jerusalem Zion established ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Enoch’s ministry have kings Great Apostasy and Earth -

An Examination of the Correlation Between the Justification and Glorification of War in Charles Mee's Iphigenia

An Examination of the Correlation Between the Justification and Glorification of War in Charles Mee’s Iphigenia 2.0: A Director’s Approach Caroline Donica Table of Contents Chapter One: Charles Mee and the History Behind Iphigenia 2.0 4 Introduction 4 The Life and Works of Charles Mee 4 Just War 8 Production History and Reception 11 Survey of Literature 13 Conclusion 15 Chapter Two: Play Analysis 16 Introduction 16 Synopsis 16 Given Circumstances 24 Previous Action 26 Dialogue and Imagery 27 Character Analysis 29 Idea and Theme 34 Conclusion 36 Chapter Three: The Design Process 37 Introduction 37 Production Style 37 Director’s Approach 38 Choice of Stage 38 Collaboration with Designers 40 Set Design 44 Costumes 46 Makeup and Hair 50 Properties 52 Lighting 53 Sound 55 Conclusion 56 Chapter Four: The Rehearsal Process 57 Introduction 57 Auditions and Casting 57 Rehearsals and Acting Strategies 60 Technical and Dress Rehearsals 64 Performances 65 Conclusion 67 Chapter Five: Reflection 68 Introduction 68 Design 68 Staging and Timing 72 Acting 73 Self-Analysis 77 Conclusion 80 Appendices 82 A – Photos Featuring the Set Design 83 B – Photos Featuring the Costume Design 86 C – Photos Featuring the Lighting Design 92 D – Photos Featuring the Concept Images 98 Works Consulted 102 Donica 4 Chapter One Charles Mee and the History Behind Iphigenia 2.0 Introduction Charles Mee’s Iphigenia 2.0 is a significant work in recent theatre history. The play was widely recognized and repeatedly produced for its unique take on contemporary issues, popular culture, and current events set within a framework of ancient myths and historical literature. -

The Rights of War and Peace Book I

the rights of war and peace book i natural law and enlightenment classics Knud Haakonssen General Editor Hugo Grotius uuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuu ii ii ii iinatural law and iienlightenment classics ii ii ii ii ii iiThe Rights of ii iiWar and Peace ii iibook i ii ii iiHugo Grotius ii ii ii iiEdited and with an Introduction by iiRichard Tuck ii iiFrom the edition by Jean Barbeyrac ii ii iiMajor Legal and Political Works of Hugo Grotius ii ii ii ii ii ii iiliberty fund ii iiIndianapolis ii uuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuu This book is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a foundation established to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. The cuneiform inscription that serves as our logo and as the design motif for our endpapers is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 b.c. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash. ᭧ 2005 Liberty Fund, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 09 08 07 06 05 c 54321 09 08 07 06 05 p 54321 Frontispiece: Portrait of Hugo de Groot by Michiel van Mierevelt, 1608; oil on panel; collection of Historical Museum Rotterdam, on loan from the Van der Mandele Stichting. Reproduced by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Grotius, Hugo, 1583–1645. [De jure belli ac pacis libri tres. English] The rights of war and peace/Hugo Grotius; edited and with an introduction by Richard Tuck. p. cm.—(Natural law and enlightenment classics) “Major legal and political works of Hugo Grotius”—T.p., v. -

Cherokee Nation Vs. the State of Georgia, The, 30 US

THE DECISIONS or THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES AT •IANUARY TERM 1831. THE CHrtoKnE NATION VS. THE STATn Op GEORGIA. Motion for an injunction to prevent the execution of certain acts of the legisla- ture df the state of Georgia in the territory of the Cherokee nation of Indians, on behalf of the Cherokee nation; they claiming to proceed in the supreme court of the United States as a foreign st;'te against the state of Georgia; under the provision of the constitution of the United States, which gives to the court jurisdiction in controversies in which a state of the United States. or the citizens thereof, and a foreign state, citizens, or subjects thereof, are parties. The Cherokee nation is not a foreign state, in the sense in which the term "foreign state" is used in the constitution of the United States. The third article of the constitution of the United States describes the extent of the judicial power. The second section'closes an enumeration of the cases to which it extends, with "controversies between a state or the citizens thereof, and foreign states, citizens or subjects," A subsequent clause of the same section gives the supreme court original jurisdiction in all cases in which a state shall be a party-the state of Georgia may then certainly be sued in this court. The Cherokees are a state. They have been uniformly treated as a state since the settlement of our country. The numerois treaties made with them by the United States recognize them as a people capable of maintaining the relations. -

Tolstoy in Prerevolutionary Russian Criticism

Tolstoy in Prerevolutionary Russian Criticism BORIS SOROKIN TOLSTOY in Prerevolutionary Russian Criticism PUBLISHED BY THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS FOR MIAMI UNIVERSITY Copyright ® 1979 by Miami University All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Sorokin, Boris, 1922 Tolstoy in prerevolutionary Russian criticism. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Tolstoi, Lev Nikolaevich, graf, 1828-1910—Criticism and interpretation—History. 2. Criticism—Russia. I. Title. PG3409.5.S6 891.7'3'3 78-31289 ISBN 0-8142-0295-0 Contents Preface vii 1/ Tolstoy and His Critics: The Intellectual Climate 3 2/ The Early Radical Critics 37 3/ The Slavophile and Organic Critics 71 4/ The Aesthetic Critics 149 5/ The Narodnik Critics 169 6/ The Symbolist Critics 209 7/ The Marxist Critics 235 Conclusion 281 Notes 291 Bibliography 313 Index 325 PREFACE Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) has been described as the most momen tous phenomenon of Russian life during the nineteenth century.1 Indeed, in his own day, and for about a generation afterward, he was an extraordinarily influential writer. During the last part of his life, his towering personality dominated the intellectual climate of Russia and the world to an unprecedented degree. His work, moreover, continues to be studied and admired. His views on art, literature, morals, politics, and life have never ceased to influence writers and thinkers all over the world. Such interest over the years has produced an immense quantity of books and articles about Tolstoy, his ideas, and his work. In Russia alone their number exceeded ten thousand some time ago (more than 5,500 items were published in the Soviet Union between 1917 and 1957) and con tinues to rise. -

The Philosophy of the Good and the Evil in the Teachings of Leo Tolstoy and Hannah Arendt

Svetlana Klimova THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE GOOD AND THE EVIL IN THE TEACHINGS OF LEO TOLSTOY AND HANNAH ARENDT BASIC RESEARCH PROGRAM WORKING PAPERS SERIES: HUMANITIES WP BRP 150/HUM/2017 This Working Paper is an output of a research project implemented at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE). Any opinions or claims contained in this Working Paper do not necessarily reflect the views of HSE Svetlana Klimova1 THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE GOOD AND THE EVIL IN THE TEACHINGS OF LEO TOLSTOY AND HANNAH ARENDT2 The main subject of this article is devited of analyses a problem of Good and Evil in the teaching of Leo Tolstoy and Hannah Arendt. each in his epoch and by a similar way, got to the back of contradictions between “reasonableness”, “morality” and a human behavior in the state and society though they approached them from the opposing points of view. The approach of Tolstoy was Christian-ethical while that of Arendt was philosophic-political. Their congeniality is attributed to the fact that the ethics of Tolstoy and the policy of Arendt are built on a common theoretical ground, i.e. the philosophical anthropology of Kant. In the “man-state” opposition, Tolstoy revealed the ethical prerequisites to creation of the totalitarian ideology, and Arendt showed up the historical, political and inhuman essence of the totalitarianism phenomenon as such. Key words: Good, Evil, radical and banality evil, a philosophical anthropology of Kant , consciousness, the mass society and the mass man, “Eichmann as man” and “Eichmann as Nazi official,” independent thinking. JEL Classification: Z 1 National Research University Higher School of Economic (Moscow, Russia); Department of Philosophy. -

The Returning Warrior and the Limits of Just War Theory

THE RETURNING WARRIOR AND THE LIMITS OF JUST WAR THEORY R.J. Delahunty Professor of Law University of St. Thomas School of Law* In this essay, I seek to explore a Christian tradition that is nei- ther the just war theory nor pacifism. Unlike pacifism, this tradi- tion teaches that war is a necessary and inescapable aspect of the human condition, and that Christians cannot escape from engaging in it. Unlike just war theory, this tradition holds that engaging in war is intrinsically sinful, however justifiable that activity may be considered to be in the light of human law, morality or reason. Mi- chael Walzer captured the essence of this way of thinking in a cele- brated essay on the problem of “dirty hands.”1 Although Walzer’s essay was chiefly about political rather than military action, he rightly observed that there was a strand in Christian reflection that saw killing, whether in a just or unjust war, as defiling or even sin- ful, even if it conformed to moral and legal standards. That tradi- tion, though subordinate, still survives in Christian, especially Lu- theran, thought. The Church’s thought about war and peace went through sever- al phases before finally settling on the just war theory. Throughout much of the Middle Ages, the Church’s approach to war was pri- marily pastoral and unsystematic. Although opinions varied widely depending on the circumstances, the early medieval Church was commonly skeptical of the permissibility of killing in warfare. Ra- ther, the Church at that time tended to the view that killing – even in a just war – was sinful and required penance. -

War in Heaven (Pdf)

"WAR IN HEAVEN - THE OUTCOME" By Don Krider God, we thank you that we have the invitation to come into the presence of the living God. We are desirous, above everything else, that the Holy Ghost of God will teach us the things of the Lord that will cause us not to hear with the natural, but Lord, to open up that spiritual ear to receive what you have for our spirit man. God, we are not people of darkness but of the light, and God, that light is in the Spirit. It is light that is life and I am asking You to bring it to us in the power and the might of Your Holy Spirit, in Jesus' mighty name! Amen! I want to bring you a topic that the Lord laid on my heart years ago. It's going to open a key to something we need to understand in Christ and when we understand this we will never be bound again. You see, the devil cannot bind you. "He whom the Son sets free is free, indeed" (John 8:36). It's us who bind ourselves. If we are going to move in the liberty of God we are going to have to know the word of God as it is written. Many times we read the word of God with natural eyes and try to get a natural understanding out of it, and all we get is fear. Maybe all we can see in Revelation is monsters and all kinds of horrible things, but I want to show you something. -

C:\Sermons on Revelation\They Came to Life and Reigned with Christ

“They Came to Life and Reigned With Christ for a Thousand Years” Sermons on the Book of Revelation # 28 Texts: Revelation 20:1-15; Ezekiel 39:1-8 ____________________________________ or many Christians, the mere mention of the millennium (the thousand years of Revelation 20) brings to mind images of lions lying down with lambs, children safely playing with poisonous Fsnakes and Jesus ruling over all the nations of the earth while seated on David’s throne in the city of Jerusalem. It is argued that Jesus’ rule guarantees a one thousand-year period of universal peace upon the earth. But is this really what we find in Revelation chapter 20? No, it is not. The question of the millennial reign of Jesus Christ and the proper interpretation of Revelation 20 has been a divisive one almost from the beginning of the Christian church. In those churches in which I was raised, premillennialism was regarded as a test of orthodoxy and anyone who wasn’t premillennial was probably either a theological liberal or a Roman Catholic, neither of whom took the plain teaching of the Bible very seriously. Premillennialism, which is far and away the dominant view held by American evangelicals, teaches that in Revelation 20, John is describing that period of time after Jesus Christ returns to earth. At first glance, the premillennial argument is iron-clad. If Revelation 19 describes Jesus Christ’s second coming, then what follows in Revelation 20 must describe what happens after Christ’s return. On this view, Christ’s return comes before the thousand years begin, hence his coming is “pre” millennial, or before the millennial age. -

Three Theories of Just War: Understanding Warfare As a Social Tool Through Comparative Analysis of Western, Chinese, and Islamic Classical Theories of War

THREE THEORIES OF JUST WAR: UNDERSTANDING WARFARE AS A SOCIAL TOOL THROUGH COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF WESTERN, CHINESE, AND ISLAMIC CLASSICAL THEORIES OF WAR A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN PHILOSOPHY MAY 2012 By Faruk Rahmanović Thesis Committee: Tamara Albertini, Chairperson Roger T. Ames James D. Frankel Brien Hallett Keywords: War, Just War, Augustine, Sunzi, Sun Bin, Jihad, Qur’an DEDICATION To my parents, Ahmet and Nidžara Rahmanović. To my wife, Majda, who continues to put up with me. To Professor Keith W. Krasemann, for teaching me to ask the right questions. And to Professor Martin J. Tracey, for his tireless commitment to my success. 1 ABSTRACT The purpose of this analysis was to discover the extent to which dictates of war theory ideals can be considered universal, by comparing the Western (European), Classical Chinese, and Islamic models. It also examined the contextual elements that drove war theory development within each civilization, and the impact of such elements on the differences arising in war theory comparison. These theories were chosen for their differences in major contextual elements, in order to limit the impact of contextual similarities on the war theories. The results revealed a great degree of similarities in the conception of warfare as a social tool of the state, utilized as a sometimes necessary, albeit tragic, means of establishing peace justice and harmony. What differences did arise, were relatively minor, and came primarily from the differing conceptions of morality and justice within each civilization – thus indicating a great degree of universality to the conception of warfare. -

1. Letter to Amrit Kaur 2. Letter to Sushila Nayyar

1. LETTER TO AMRIT KAUR LIKANDA February 23, 1940 MY DEAR IDIOT, Though we have hostile slogans1, on the whole, things have gone smooth.One never knows when they may grow worse. The atmosphere is undoubtedly bad. The weather is superb. I am keeping excellent and have regular hours. The b.p. is under control. Radical changeshave been made in the workingand composition of the Sangh.2 This you will have already seen. We are leaving here on Sunday and leaving Calcutta on Tuesday for Patna3. No more today. Mountain of work awaiting me. Your reports about the family there are encouraging. Poonam Chand Ranka4 told me he was going to correspond directly with Balkrishna about Chindwara. Evidently he has done nothing. This is unfortunate. Love to all. BAPU From the original : C.W. 3962. Courtesy : Amrit Kaur. Also G.N. 7271 2. LETTER TO SUSHILA NAYYAR February 23, 1940 CHI. SUSHILA, There is no news from you. How is Parachure Shastri? I have written to Biyaniji at Chhindwada. I hope Balkrishna and Kunverji are able to bear the heat. I am keeping perfectly good health. Blessings from BAPU From the Hindi original: Pyarelal Papers. Nehru Memorial Museum and Library. Courtesy: Dr. Sushila Nayyar 1 Vide “Speech at Khadi and Village Industries Exhibition”, 20-2-1940 2 Vide “Speech at Gandhi Seva Sangh Meeting—IV”, pp. 22-2-1940 3 For the Congress Working Committee meeting 4 President, Provincial Congress Committee, Nagpur VOL. 78 : 23 FEBRUARY, 1940 - 15 JULY, 1940 1 3. TELEGRAM TO SUSHILA NAYYAR GANDHI SEVA SANGH, February 24, 1940 SUSHILA SEGAON WARDHA TELL VALJIBHAI TAKE MILK TREATMENT WITH REST. -

AJ Muste's Theology

! A.J. Muste’s Theology: Tracing the Ideas that Shaped the Man Jeffrey D. Meyers M.A. Thesis Earlham School of Religion April 16, 2012 ! Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1: A Short Biography 4 Chapter 2: The Theological Task 14 Chapter 3: Mysticism and the Inner Life 22 Chapter 4: The Social Gospel 34 Chapter 5: The Way of Love, the Way of the Cross 43 Chapter 6: Theological Anthropology 61 Chapter 7: Ecclesiology 81 Chapter 8: Eschatology: The Kingdom of God 101 Conclusions 115 Annotated Bibliography 121 Appendix 1a: Books Owned By Muste 150 Appendix 1b: Books Owned By Muste 158 Appendix 2: Authors Cited By Muste 176 Appendix 3: Books Assigned By Muste 191 Introduction Historians study the Reverend Abraham Johannes Muste primarily for his shaping of the labor movement of the 1920s and 1930s, his work for peace from the mid 1930s through the 1960s, and his involvement in laying the foundations of the Civil Rights Movement.1 His leadership in these movements often gained him national attention––Time Magazine once labeled him “the No. 1 U.S. Pacifist.”2 Although most attempts at understanding this complex man have noted the influence of his Christian faith, few scholars have explored its true depth. The religious foundations of his life, thought, and work were often an embarrassment to those he worked with and those who admired him. In avoiding Muste’s faith, his contemporaries and scholars alike have missed the ways his theology undergirded and motivated his life and work. At heart, Muste was a theologian.