Let Us Know How Access to This Document Benefits You

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 5/29/2020 Anaheim Ducks Chicago Blackhawks 1185299 NHL recognizes Presidents’ Trophy, scoring title and 1185325 Mayor Lori Lightfoot backs Chicago’s bid to be one of the goaltending award winners NHL’s playoff hubs — if the city meets safety protoc 1185300 Finding an NHL comparable for 10 of the Ducks’ best 1185326 Former Hinsdale home of ex-Blackhawks coach and site prospects of Stanley Cup toilet paper high jinks lists for $2.6 mil 1185327 Chicago as an NHL playoffs hub? Evaluating the city’s Arizona Coyotes chance to host hockey this summer 1185301 Shane Doan believes Coyotes can take advantage of 1185328 Report: NHL training camps for 24-team playoff won't NHL’s 24-team playoff open before July 10 1185302 Imperfect and incomplete, NHL’s return plan good news 1185329 How Blackhawks are impacted by NHL counting play-in for Coyotes results as playoff stats 1185330 Why Corey Crawford, Dominik Kubalik could decide Boston Bruins Blackhawks-Oilers series 1185303 Zdeno Chara is grateful for the chance to play, even if 1185331 NHL playoff format could hurt Oilers, but Connor McDavid restart plan is flawed won’t complain 1185304 A ‘grateful’ Zdeno Chara eager for hockey’s return 1185332 Blackhawks could be getting help on defense from Ian 1185305 Bruins earn regular season awards Mitchell for play-in series 1185306 Ranking the best Bruins teams that failed to win Stanley 1185333 Ex-Blackhawks coach Joel Quenneville's house listed for Cup $2.6 million 1185307 Zdeno Chara 'grateful for the opportunity' to play, not -

Annual Report of the Town of North Hampton, New Hampshire

r «?0|| && ^umf^omted -Z7-40 ruEH0ARsfi L, T eA ' £:> ; 2> '.'- S : ' - ^>«T t**— - - - - - -"-- ..; *r., f. 1 if 'm : -» JV; s.»:>&. ' 'nMiriJltnT 1tr*ii»fW '-**-•> .(a.mks r„i;A('iii:U)HU. R.'R. -Stats on I.ITTI K UuAK'S III AH.X.H. SOUTH HAMPTiiVVU. <3S> ^ 3%fca/ @fyea* ^nded Jime 30, 20/V - EMERGENCY NUMBERS - FIRE EMERGENCY 9-1-1 AMBULANCE EMERGENCY 9-1-1 POLICE EMERGENCY 9-1-1 - TELEPHONE DIRECTORY - Administration 964-8087 Assessing 964-8087 Building Inspector 964-8650 Town Clerk/Tax Collector 964-6029 Fire (routine business only) 964-5500 Police (routine business only) 964-8621 Public Works Department 964-6442 Recycling Center/Brush Dump 964-9825 Planning & Zoning 964-8650 Recreation 964-3170 Public Library 964-6326 North Hampton School 964-5501 Winnacunnet High School 926-3395 - HOURS OPEN TO THE PUBLIC - Town Offices 8:00 a.m. -4:00 p.m. Monday through Friday Town Clerk/Tax Collector 8:30 a.m. -7:00 p.m. Monday 8:30 a.m. - 3:00 p.m. Tuesday through Friday Public Library 10:00 a.m. -5:00 p.m. Monday,Wednesday, Friday 10:00 a.m. -8:00 p.m. Tuesday, Thursday 10:00 a.m. -2:00 p.m. Saturday Recycling Center 8:00 a.m. -12:00 p.m. Wednesday and Saturday 1:00 p.m. -5:00 p.m. Brush Dump April - November Saturday 8:00 a.m. -12:00 p.m. 1:00 p.m. -5:00 p.m. - MEETING SCHEDULES nd th Select Board 7:00 p.m. -

Mayoral Hopefuls Lay out Their Visions for Town Can't Keep" He Said Regarding a the KECORD-HHKSS Simple Solution to Increasing Taxes

l&nttrb ttBB Serving Westfield, Scotch Plains and Fanwood VOL £\Jt 1 * |jj ijfi ijj Friday, October 7, 2005 50 cents 3 tf.' 3 Mayoral hopefuls lay out their visions for town can't keep" he said regarding a THE KECORD-HHKSS simple solution to increasing taxes. Substantially reducing WESTFIELD — Republican expenses would mean "cutting Andy Skibitsky and Democrat back on important services" such Tom Jnrdim both say they want as police positions, he said, some- to be elected mayor because they thing he and the town do not love working hard to get results want to consider. — but in interviews this week, The best way to stem the the two candidates offered some growth of the tax rate, Skibitsky sharply different ideas on how to said, is to continue to review the achieve the best outcomes on effectiveness and efficiency of the Rowbotham stars, property taxes, development and town's departments. other issues. Jardim agreed that with but Raiders fall With the general election structural forces driving up the scheduled Nov. 8. Skibitsky, a town's obligations, the best thing Plains-Fanwood wide receiver councilman who assumed the to do would be to stabilize taxes Kyle Rowbotham had a huge game mayor's post when Republican and prevent rapidly increasing or against Cranford Friday night — nine Greg McDcrmott resigned in decreasing taxes from year to catches, 144 yards, three touchdowns June, is seeking another lour year. But he said he saw a chance — but the Haiders came up just short, years, while Jardim, who served to increase revenue in some losing 26-23 in overtime. -

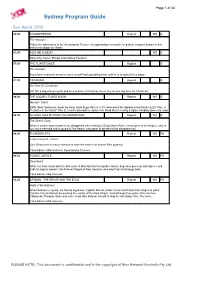

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 34 Sydney Program Guide Sun Aug 5, 2012 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G The Imposter Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G Hosted by Lauren Phillips and Andrew Faulkner. 07:00 THE FLINTSTONES Repeat G The Gambler Psychiatric treatment seems to have cured Fred's gambling fever until he is tempted into a wager. 07:30 TAZ-MANIA Repeat G No Time For Christmas Taz fills a bag with presents and tries to deliver Christmas cheer, but no one has time for Christmas. 08:00 THE LOONEY TUNES SHOW Repeat WS G Monster Talent Daffy takes Gossamer under his wing, while Bugs stars in a TV commercial for Speedy's new frozen pizza. Plus, in "A Zipline in the Sand," Wile E. Coyote attempts to capture the Road Runner using a zipline hanging above the road. 08:30 SCOOBY DOO MYSTERY INCORPORATED Repeat WS G The Siren's Song When a sardine boat mysteriously disappears when fishing in Dead Man's Point, Velma goes to investigate, only to run into a mermaid and a couple of fish freaks, who seem to be behind the disappearings. 09:00 THUNDERCATS Repeat WS PG Trials of Lion-O - Part 2 Lion-O launches a rescue mission to save the team from Mumm-Ra's pyramid. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence, Supernatural Themes 09:30 YOUNG JUSTICE Repeat WS PG Disordered While the team deals with the aftermath of Miss Martian's telepathic attack, Superboy goes out with Sphere and finds its original owners: the Forever People of New Genesis, who want their technology back. -

AN ANALYSIS of CULTURAL BARRIER FACED by SCOTT THOMAS AS AMERICAN TRAVELER in ALEC BERG's FILM “EUROTRIP” THESIS By: YULI

AN ANALYSIS OF CULTURAL BARRIER FACED BY SCOTT THOMAS AS AMERICAN TRAVELER IN ALEC BERG’S FILM “EUROTRIP” THESIS By: YULIANA 08360153 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF MUHAMMADIYAH MALANG NOVEMBER 2012 AN ANALYSIS OF CULTURAL BARRIER FACED BY SCOTT THOMAS AS AMERICAN TRAVELER IN ALEC BERG’S FILM “EUROTRIP” THESIS This thesis is submitted to fulfill one of the requirements to achieve Sarjana Degree in English Education By: YULIANA 08360153 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF MUHAMMADIYAH MALANG NOVEMBER 2012 This thesis written by Yuliana was approved on November 14, 2012. This thesis was defended in front of the examiners of Faculty of Teacher Training and Education of University of Muhammadiyah Malang and as one of the requirements to achieve Sarjana Degree in English Education on November 14, 2012 Approved by: Faculty of Teacher Training and Education University of Muhammadiyah Malang M O T T O : Katakanlah : “ Hai orang-orang yang beriman, jadikanlah sabar dan shalatmu sebagai penolongmu, sesungguhnya Allah beserta orang-orang yang sabar” (Surat Al-Baqarah:153) Berangkat dengan penuh keyakinan-Berjalan dengan penuh keikhlasan-Istiqomah dalam mengadapi ujian. “Yakin,Ikhlas,Istiqomah” DEDICATION : This Thesis Dedicated To : My Beloved Parents (My Father Miswadi and My Mother Yatiha) My Beloved Family (Muhammad Nanang Sujito – Siti Madenang Khaliq-Dian prizka Okta Putra-Febri Dwi Pramana Putra) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Alhamdulillahirobil’alamin my praise is gratefully only dedicated to Allah SWT. For His Almighty and Merciful guides and blesses, the writer can finish this thesis. Sholawat and Salam are always given to the prophet Muhammad SAW. -

Council Meeting Minutes September 5, 2019

Thursday, September 5, 2019 ITEM 1: CALL TO ORDER: Mayor Flaute called the Riverside, Ohio City Council Meeting to order at 6:00 p.m. at the Riverside Administrative Offices located at 5200 Springfield Street, Suite 100, Riverside, Ohio, 45431. ITEM 2: ROLL CALL: Council attendance was as follows: Ms. Campbell, present; Mr. Curp, present; Deputy Mayor Denning, present; Ms. Fry, present; Ms. Lommatzsch, present; Mr. Teaford, absent; and Mayor Flaute, present. Staff present was as follows: Mark Carpenter, City Manager, Chris Lohr, Assistant City Manager; Tom Garrett, Finance Department; Chief Frank Robinson, Police Department; Chief Dan Stitzel, Fire Department, Kathy Bartlett, Service Department; Dalma Grandjean, Law Director; and Katie Lewallen, Clerk of Council. ITEM 3: EXCUSE ABSENT MEMBERS: Ms. Lommatzsch motioned to excuse Mr. Teaford. Ms. Campbell seconded the motion. All were in favor; none opposed. Motion carried. ITEM 4: ADDITIONS OR CORRECTIONS TO AGENDA: No changes were made to the revised agenda. ITEM 5: APPROVAL OF AGENDA: Deputy Mayor Denning motioned to approve the revised agenda. Mr. Teaford seconded the motion. All were in favor; none opposed. Motion carried. ITEM 6: WORK SESSION ITEMS: A) 25 Year Certificate of Membership from Dayton Chamber – Mr. Phil Parker and an ambassador from the Dayton Area Chamber of Commerce presented the city with a certificate for 25 years of membership through supporting the chamber, the community, and the business community. Mr. Parker gave a few words about Riverside and how he and his wife started their life together in Riverside at Yorktown Colony Apartments. He commented about the Air Force Museum being a premier destination in the state and county and would mention the sign on 35 going west to Mayor Johnnie Doan how the brush would overgrow the sign. -

Issue 10 July 2021 Angel City Review Foreword

Issue 10 July 2021 Angel City Review FOREWORD Hello, friends. We here at Angel City Review extend to you our warmest greetings and our most heart- felt gratitude. To say that you all have persisted through trying times is an understatement, and we thank you for yet again sharing your time and energy and creativity and perspectives with us in ways that cannot help but facilitate our growth as people. What follows is Issue 10, a wonderful collection of art that digs into the essence of the human experience, celebrating its joys and speaking truth to its agonies. I do not think it hyperbole to suggest that we live in harlequin days, where each of our individ- ual humanities are more recognized and validated than ever before, and where they are under constant attack from power structures that can only react with violence toward the threat of empathy. At the risk of sounding like a broken record, I believe literature is a vital and essential exchange and recognition of perspectives beyond our own, and I believe such a lifeline of communication is profoundly necessary in our era. Hopefully, this collection will play some small part in keeping that line open, in helping you make that connection to others that can feel and love as you do. To all of the brilliant authors who submitted, thank you. We were blessed with an abundance of true quality, and have no doubt your talent should and will be recognized. And to everyone, thank you for all your hard work, not just in terms of your literature, but especially with regards to the very act of persisting, of being a guiding light for someone, even if you have yet to realize it. -

Lorton Inside

❖ ❖ inside Fairfax Station Clifton Lorton State of The Schools Report FallFall FunFun PagePage 33 OneOne ofof thethe visitorsvisitors atat HeatherHeather HillHill Gardens’Gardens’ FallFall FestivalFestival getsgets aa peckpeck fromfrom aa goat.goat. TheThe FairfaxFairfax StationStation gardengarden centercenter hostshosts thethe annualannual eventevent throughoutthroughout thethe monthmonth ofof October.October. Follow on Twitter: @LFSCConnection on Twitter: Follow Classified, Page 21 Classified, ❖ Sports, Page 20 ❖ , Page 6 Calendar Month of Art At Workhouse Fall Fun, Page 3 Clifton Day 9-30-11 home in Requested Time sensitive material. sensitive Time Around Postmaster: Attention PERMIT #322 PERMIT Easton, MD Easton, The Corner PAID U.S. Postage U.S. News, Page 4 STD PRSRT Photo courtesy of Bonnie Ruetenik online at www.connectionnewspapers.com www.ConnectionNewspapers.comSeptember 29-October 5, 2011 Fairfax Station/Clifton/Lorton Connection ❖ September 29 - October 5, 2011 ❖ 1 Top Producing Realtors News Is your business growing? Do you need more space? Labovitz Private & Semi Private space available. Phones, internet Sentenced on open access, printers, fax, digital scan, email, web presence & more are yours with no fees. Fun & professional office Misdemeanors environment, full time non selling management & staff, in Peter Labovitz, President and office training & coaching available. Your business, your way CEO of Connection Newspapers, with our assistance. And, now, with the best compensation has been sentenced to six months plan in the business. Check us out! for two misdemeanor counts of failing to fully pay the company’s Jon Wolford, Branch Vice President payroll taxes for two quarters in Long & Foster Springfield , 7202 Old Keene Mill Rd, Springfield VA 2007 in a timely manner. -

Spiro Kalavritinos

R e f l e c t i o n S t a t e m e n t: A Multitude of Methods to Evade the Truth “I will never understand people. They’re the worst.” 1 Whilst Seinfeld 2 was hailed for its exploration of the minutiae of every- day life, the contemporary form of reality television has eschewed exploration of the inherent, intricate tensions in society, instead preferring to paint in broad, haphazard strokes. Growing up, I questioned why I could merely remember a hazy vision of characters from reality television, none of whom resembled myself, whilst my favourite show, Seinfeld, presented distinctive, inimitable voices. Over the past year, I have scrutinised this concept, understanding that reality television idealises the mundane, squandering the potential for diverse role models to evolve within the medium. My Major Work aims to expose the manipulation prevalent in the genre, 1 “The Face Painter.” Seinfeld. NBC, New York City. 11 May, 1995. Television. 2 David, Larry and Seinfeld, Jerry (Creators). (1989). Seinfeld. NBC, New York City. Television. whilst exploring the psychological ramifications of character portrayals in contemporary media. A satirical mirroring of the techniques utilised within the reality television genre is employed, heightening my criticism of the medium. Its greater purpose is thus to explore the relationship between composers and audiences, revealing the distortion of individual perceptions of society that stems from this, an insight attained through the lens of ‘reality TV’. Reflecting the genre, the work appeals to varying demographics. Those who simply have a love of fiction, intrigued by tone and experimentation, gain an insight into the reality television genre, whilst academics will appreciate the necessity and complexity of the decisions regarding this inventiveness. -

August 17 & 18, 2018

Summer 2018 August 17 & 18, 2018 Findlay Township Dog Park - is Officially Open! Findlay Township Board of Supervisors Janet L. Craig - Chairperson Thomas J. Gallant - Member Raymond L. Chappell - Vice-Chairperson In This Issue: Fair In The Woodlands ............. Front Cover On May 5, 2018 the Findlay Township dog park officially opened on the upper Findlay Township Dog Park is Officially Open! ............ Inside Front Cover level (behind the ballfield) at the Recreation & Sports Complex on Route 30 in Imperial. The official leash cutting by the Board of Supervisors was held much to Meet Our New Receptionist! ... .Inside Front Cover the pleasure of the almost 30 dogs that showed up for the festivities. The dogs were Municipal Building Additions . .1 given treat bags to welcome them to our newest park addition, along with balls and New Congressional District .................. .1 frisbees to play with. Since the official Brighter Streets and More Savings!............ .1 opening, activity at the Continuing To Honor Your Military Hero ........ .1 dog park has been very Latest from the Findlay Township busy. A water fountain Police Department ......................... .2 was recently installed Personal Security: Expert Tips for Safe Traveling ..2 that has a special dog Bogus or Legit? 10 Ways to Evaluate an E-mail .. .3 bowl that fills up with water for a refreshing SWIFTREACH 911 Notification System ......... .3 drink after playtime. Retiring the American Flag................... .3 Keep an eye out for New Business Landings ..................... .4 future additions to our dog park. Thanks to Expanding Neighborhoods................... .4 comments from our Township Sponsored Programs dog owners, we are looking at shade options, a walkway extension, agility stations, for Senior Citizens ........................ -

Sydney Program Guide

7/17/2020 prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Reports.Dsp_ELEVEN_Guide?psStartDate=02-Aug-20&psEndDate=08… SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 02nd August 2020 06:00 am Toasted TV G Toasted TV Sunday 2020 187 Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 06:05 am Dora The Explorer (Rpt) G Dora's Animalito Adventure Dora, Boots and Diego set out to rescue their bunny, turtle and butterfly animalito friends and bring them back home to their Copal Tree. 06:25 am Toasted TV G Toasted TV Sunday 2020 188 Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 06:30 am Blaze And The Monster Machines (Rpt) G Blaze Of Glory Part 1 Blaze & AJ are introduced to a world of racing Monster Machines, but when a truck named Crusher uses dirty tricks, Blaze will do everything he can to help his friends. 06:55 am Toasted TV G Toasted TV Sunday 2020 189 Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 07:00 am Paw Patrol (Rpt) G Pups And The Lighthouse Boogie/pups Save Ryder Mayor Goodway & Alex row out into the bay to get a look at a baby whale but a storm blows the rowboat towards the sea. -

Communication Through Seinfeld in 1989, Comedian Jerry Seinfeld And

Communication through Seinfeld In 1989, comedian Jerry Seinfeld and his friend, Larry David, created a sitcom called Seinfeld and within its 180 episodes, Seinfeld illustrates every possible problem modern people face. Seinfeld was pitched as 'a show about nothing,' a show that would parody the lives of four adults living in New York City. The main characters of Seinfeld are Jerry Seinfeld, co- writer and creator of the show, Elaine Benes, Jerry's ex-girlfriend, Cosmo Kramer, Jerry's neighbor, and George Costanza, Jerry's best friend. Through nine years of airtime, Seinfeld has touched base on every aspect of life, comedy, romance, sex, sports, religion, and sociology, and somehow made all of these aspects humorous. Through this semester in Communication 200, we have studied the five units, or lenses, that are the foundations of communication theories. These lenses include: interpersonal communication, group and public communication, persuasion, mass communication, and cultural context. Although these lenses contain many theories of communication, Seinfeld can be used as a tool to help illustrate the majority of these theories. Since I've been a viewer of Seinfeld since I can remember, I thought my knowledge of the sitcom would never get me anywhere past scoring a point on Trivial Pursuit, but through learning communication theories, I see Seinfeld as an excellent way to illustrate and explain communication. The first unit we looked at as a class was a general overview of communication and how to study the theories we would be looking at for the rest of the semester. Theories fall between two different approaches, the objective and interpretive.