Using Racial Humor at Work: Promoting Positive Discussions on Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 5/29/2020 Anaheim Ducks Chicago Blackhawks 1185299 NHL recognizes Presidents’ Trophy, scoring title and 1185325 Mayor Lori Lightfoot backs Chicago’s bid to be one of the goaltending award winners NHL’s playoff hubs — if the city meets safety protoc 1185300 Finding an NHL comparable for 10 of the Ducks’ best 1185326 Former Hinsdale home of ex-Blackhawks coach and site prospects of Stanley Cup toilet paper high jinks lists for $2.6 mil 1185327 Chicago as an NHL playoffs hub? Evaluating the city’s Arizona Coyotes chance to host hockey this summer 1185301 Shane Doan believes Coyotes can take advantage of 1185328 Report: NHL training camps for 24-team playoff won't NHL’s 24-team playoff open before July 10 1185302 Imperfect and incomplete, NHL’s return plan good news 1185329 How Blackhawks are impacted by NHL counting play-in for Coyotes results as playoff stats 1185330 Why Corey Crawford, Dominik Kubalik could decide Boston Bruins Blackhawks-Oilers series 1185303 Zdeno Chara is grateful for the chance to play, even if 1185331 NHL playoff format could hurt Oilers, but Connor McDavid restart plan is flawed won’t complain 1185304 A ‘grateful’ Zdeno Chara eager for hockey’s return 1185332 Blackhawks could be getting help on defense from Ian 1185305 Bruins earn regular season awards Mitchell for play-in series 1185306 Ranking the best Bruins teams that failed to win Stanley 1185333 Ex-Blackhawks coach Joel Quenneville's house listed for Cup $2.6 million 1185307 Zdeno Chara 'grateful for the opportunity' to play, not -

Annual Report of the Town of North Hampton, New Hampshire

r «?0|| && ^umf^omted -Z7-40 ruEH0ARsfi L, T eA ' £:> ; 2> '.'- S : ' - ^>«T t**— - - - - - -"-- ..; *r., f. 1 if 'm : -» JV; s.»:>&. ' 'nMiriJltnT 1tr*ii»fW '-**-•> .(a.mks r„i;A('iii:U)HU. R.'R. -Stats on I.ITTI K UuAK'S III AH.X.H. SOUTH HAMPTiiVVU. <3S> ^ 3%fca/ @fyea* ^nded Jime 30, 20/V - EMERGENCY NUMBERS - FIRE EMERGENCY 9-1-1 AMBULANCE EMERGENCY 9-1-1 POLICE EMERGENCY 9-1-1 - TELEPHONE DIRECTORY - Administration 964-8087 Assessing 964-8087 Building Inspector 964-8650 Town Clerk/Tax Collector 964-6029 Fire (routine business only) 964-5500 Police (routine business only) 964-8621 Public Works Department 964-6442 Recycling Center/Brush Dump 964-9825 Planning & Zoning 964-8650 Recreation 964-3170 Public Library 964-6326 North Hampton School 964-5501 Winnacunnet High School 926-3395 - HOURS OPEN TO THE PUBLIC - Town Offices 8:00 a.m. -4:00 p.m. Monday through Friday Town Clerk/Tax Collector 8:30 a.m. -7:00 p.m. Monday 8:30 a.m. - 3:00 p.m. Tuesday through Friday Public Library 10:00 a.m. -5:00 p.m. Monday,Wednesday, Friday 10:00 a.m. -8:00 p.m. Tuesday, Thursday 10:00 a.m. -2:00 p.m. Saturday Recycling Center 8:00 a.m. -12:00 p.m. Wednesday and Saturday 1:00 p.m. -5:00 p.m. Brush Dump April - November Saturday 8:00 a.m. -12:00 p.m. 1:00 p.m. -5:00 p.m. - MEETING SCHEDULES nd th Select Board 7:00 p.m. -

The Chinese in Hawaii: an Annotated Bibliography

The Chinese in Hawaii AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY by NANCY FOON YOUNG Social Science Research Institute University of Hawaii Hawaii Series No. 4 THE CHINESE IN HAWAII HAWAII SERIES No. 4 Other publications in the HAWAII SERIES No. 1 The Japanese in Hawaii: 1868-1967 A Bibliography of the First Hundred Years by Mitsugu Matsuda [out of print] No. 2 The Koreans in Hawaii An Annotated Bibliography by Arthur L. Gardner No. 3 Culture and Behavior in Hawaii An Annotated Bibliography by Judith Rubano No. 5 The Japanese in Hawaii by Mitsugu Matsuda A Bibliography of Japanese Americans, revised by Dennis M. O g a w a with Jerry Y. Fujioka [forthcoming] T H E CHINESE IN HAWAII An Annotated Bibliography by N A N C Y F O O N Y O U N G supported by the HAWAII CHINESE HISTORY CENTER Social Science Research Institute • University of Hawaii • Honolulu • Hawaii Cover design by Bruce T. Erickson Kuan Yin Temple, 170 N. Vineyard Boulevard, Honolulu Distributed by: The University Press of Hawaii 535 Ward Avenue Honolulu, Hawaii 96814 International Standard Book Number: 0-8248-0265-9 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-620231 Social Science Research Institute University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Copyright 1973 by the Social Science Research Institute All rights reserved. Published 1973 Printed in the United States of America TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD vii PREFACE ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xi ABBREVIATIONS xii ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY 1 GLOSSARY 135 INDEX 139 v FOREWORD Hawaiians of Chinese ancestry have made and are continuing to make a rich contribution to every aspect of life in the islands. -

Let Us Know How Access to This Document Benefits You

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1998 Consolation Deborah Siegel The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Siegel, Deborah, "Consolation" (1998). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1892. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1892 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of MONTANA Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature ** Yes, I grant permission X No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature Date Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. Consolation by Deborah Siegel B.A., Macalester College, 1996 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Fine Arts University of Montana 1998 Approved by: Thesis Committee Chair Dean, Graduate School Date UMl Number: EP36427 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Post-9/11 Brown and the Politics of Intercultural Improvisation A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE “Sound Come-Unity”: Post-9/11 Brown and the Politics of Intercultural Improvisation A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker September 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Deborah Wong, Chairperson Dr. Robin D.G. Kelley Dr. René T.A. Lysloff Dr. Liz Przybylski Copyright by Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker 2019 The Dissertation of Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments Writing can feel like a solitary pursuit. It is a form of intellectual labor that demands individual willpower and sheer mental grit. But like improvisation, it is also a fundamentally social act. Writing this dissertation has been a collaborative process emerging through countless interactions across musical, academic, and familial circles. This work exceeds my role as individual author. It is the creative product of many voices. First and foremost, I want to thank my advisor, Professor Deborah Wong. I can’t possibly express how much she has done for me. Deborah has helped deepen my critical and ethnographic chops through thoughtful guidance and collaborative study. She models the kind of engaged and political work we all should be doing as scholars. But it all of the unseen moments of selfless labor that defines her commitment as a mentor: countless letters of recommendations, conference paper coachings, last minute grant reminders. Deborah’s voice can be found across every page. I am indebted to the musicians without whom my dissertation would not be possible. Priya Gopal, Vijay Iyer, Amir ElSaffar, and Hafez Modirzadeh gave so much of their time and energy to this project. -

Mayoral Hopefuls Lay out Their Visions for Town Can't Keep" He Said Regarding a the KECORD-HHKSS Simple Solution to Increasing Taxes

l&nttrb ttBB Serving Westfield, Scotch Plains and Fanwood VOL £\Jt 1 * |jj ijfi ijj Friday, October 7, 2005 50 cents 3 tf.' 3 Mayoral hopefuls lay out their visions for town can't keep" he said regarding a THE KECORD-HHKSS simple solution to increasing taxes. Substantially reducing WESTFIELD — Republican expenses would mean "cutting Andy Skibitsky and Democrat back on important services" such Tom Jnrdim both say they want as police positions, he said, some- to be elected mayor because they thing he and the town do not love working hard to get results want to consider. — but in interviews this week, The best way to stem the the two candidates offered some growth of the tax rate, Skibitsky sharply different ideas on how to said, is to continue to review the achieve the best outcomes on effectiveness and efficiency of the Rowbotham stars, property taxes, development and town's departments. other issues. Jardim agreed that with but Raiders fall With the general election structural forces driving up the scheduled Nov. 8. Skibitsky, a town's obligations, the best thing Plains-Fanwood wide receiver councilman who assumed the to do would be to stabilize taxes Kyle Rowbotham had a huge game mayor's post when Republican and prevent rapidly increasing or against Cranford Friday night — nine Greg McDcrmott resigned in decreasing taxes from year to catches, 144 yards, three touchdowns June, is seeking another lour year. But he said he saw a chance — but the Haiders came up just short, years, while Jardim, who served to increase revenue in some losing 26-23 in overtime. -

1 This Isn't Paradise, This Is Hell: Discourse, Performance and Identity in the Hawai'i Metal Scene a Dissertation Submitte

1 THIS ISN’T PARADISE, THIS IS HELL: DISCOURSE, PERFORMANCE AND IDENTITY IN THE HAWAI‘I METAL SCENE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN AMERICAN STUDIES DECEMBER 2012 By Benjamin Hedge Olson Dissertation Committee: Kathleen Sands, Chairperson David E. Stannard Vernadette Gonzalez Roderick Labrador Helen J. Baroni Keywords: metal, popular music, popular culture, religion, subculture, Hawai‘i 2 Abstract The island of Oahu is home to probably the most ethnically diverse metal scene in the United States. Contemporary Hawai`i prides itself on being a “model of multiculturalism” free of the racism and ethnic strife that is endemic to the continent; however, beneath this superficial openness and tolerance exist deeply felt class, ethnic, and racial tensions. The metal scene in Hawai`i experiences these conflicting impulses towards inclusion and exclusion as profoundly as any other aspect of contemporary Hawaiian culture, but there is a persistent hope within the metal scene that subcultural identity can triumph over such tensions. Complicating this process is the presence of white military personnel, primarily born and raised on the continental United States, whose cultural attitudes, performances of masculinity, and conception of metal culture differ greatly from that of local metalheads. The misunderstandings, hostilities, bids for subcultural capital, and attempted bridge-building that take place between metalheads in Hawai‘i constitute a subculturally specific attempt to address anxieties concerning the presence of the military, the history of race and racism in Hawai`i, and the complicated, often conflicting desires for both openness and exclusivity that exist within local culture. -

Schedule F-2 by Last Name

Schedule F-2 by Last Name ID Country Name Country Code Last Name, First Contingent Unliquidated Disputed Amount 1204096 Paraguay (PY) W A GOMES, MATHEUS RAMON X X X UNKNOWN 921652 Malaysia (MY) W ABD MUHAIMI, W MUHAMMAD FAIZ X X X UNKNOWN 1649270 United States (US) W CABRERA, PEDRO X X X UNKNOWN 1719541 United States (US) W DALMAN GENERAL SERVICES X X X UNKNOWN 1776164 Uruguay (UY) W DE LIMA, JOSE X X X UNKNOWN 956360 Netherlands (NL) W J M HOFHUIS X X X UNKNOWN 745344 Haiti (HT) W JUNIOR, JEAN X X X UNKNOWN 758668 Indonesia (ID) W KUENGO, SYARIF X X X UNKNOWN 956361 Netherlands (NL) W L BEUVING X X X UNKNOWN 1669241 United States (US) W LEMOS, RODRIGO X X X UNKNOWN 956362 Netherlands (NL) W M J HOFHUIS, W M J HOFHUIS X X X UNKNOWN 676497 Spain (ES) W M LIMA, RAQUEL X X X UNKNOWN 1301880 Tanzania (TZ) W MREMA, FREDRICK X X X UNKNOWN 1551784 United States (US) W O REIS, JOSE X X X UNKNOWN 921760 Malaysia (MY) W OMAR, WAN NORRIZAROS X X X UNKNOWN 1480191 United States (US) W Q GUSS, FABIO X X X UNKNOWN 1480192 United States (US) W QUINTINO GUSS, FABIO X X X UNKNOWN 1445973 United States (US) W RABKE JR, DAVID X X X UNKNOWN 1830388 China (CN) W, 1 X X X UNKNOWN 1842807 Cambodia (KH) W, 1 X X X UNKNOWN 1851171 United States (US) W, 1 X X X UNKNOWN 1830593 China (CN) W, 123456 X X X UNKNOWN 1838893 Spain (ES) W, 2 X X X UNKNOWN 1852261 United States (US) W, 3 X X X UNKNOWN 1828995 Bolivia (BO) W, A X X X UNKNOWN 1841014 Hong Kong (HK) W, A X X X UNKNOWN 1843854 Mexico (MX) W, A X X X UNKNOWN 1831883 China (CN) W, A X X X UNKNOWN 1842929 Cambodia -

Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation Within American Tap Dance Performances of The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 © Copyright by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 by Brynn Wein Shiovitz Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Susan Leigh Foster, Chair Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950, looks at the many forms of masking at play in three pivotal, yet untheorized, tap dance performances of the twentieth century in order to expose how minstrelsy operates through various forms of masking. The three performances that I examine are: George M. Cohan’s production of Little Johnny ii Jones (1904), Eleanor Powell’s “Tribute to Bill Robinson” in Honolulu (1939), and Terry- Toons’ cartoon, “The Dancing Shoes” (1949). These performances share an obvious move away from the use of blackface makeup within a minstrel context, and a move towards the masked enjoyment in “black culture” as it contributes to the development of a uniquely American form of entertainment. In bringing these three disparate performances into dialogue I illuminate the many ways in which American entertainment has been built upon an Africanist aesthetic at the same time it has generally disparaged the black body. -

Haole Matters: an Interrogation of Whiteness in Hawai'i

l/637 )(jJ~ 263 HAOLE MATTERS: AN INTERROGATION OF WHITENESS IN HAWAI'I A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DMSION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFULLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE AUGUST 2005 By Judy L. Rohrer Dissertation Committee: Kathy E. Ferguson, Chairperson Phyllis Turnbull Noenoe K. Silva Jonathan Goldberg-Hiller David Stannard iii © Copyright 2005 by Judy L. Rohrer All Rights Reserved iv This work is dedicated with respect and aloha to the women who were, and are my inspiration my grandmother, mother, and niece: Estella Acevedo Kasnetsis (1908-1975) Georgia Kasnetsis Acevedo (1938- ) Ho'ohila Estella Kawelo (2002-) v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is impossible to thank all who contributed to this dissertation. I can only send a heartfelt mahalo out into the universe and trust it will light in the right places. For their unwavering support and guidance through this process, I thank my outstanding committee. My chair, Kathy Ferguson has been both friend and mentor, nurturing my theoretical growth, challenging stale thinking, and encouraging curiosity over moralizing. For all the parts of this dissertation that deal with Hawaiian culture and history and so many more, I am indebted to Noenoe Silva for her close read, gentle corrections, suggested sources, and inquisitive questions. Phyllis Turnbull has been my compass, always to the point ("rein itin, Bubba") and unfailingly supportive in times of doubt (''Breathe deeply. There is a god and she is still on our side"). Jon Goldberg~Hiller introduced me to critical legal theory and made the revolutionary s~ggestion that I defend ahead of schedule. -

Global Invasive Plants in Thailand and Its Status and a Case Study of Hydrocotyle Umbellata L

Global invasive plants in Thailand and its status and a case study of Hydrocotyle umbellata L. Siriporn Zungsontiporn Weed Science Group, Plant Protection Research and Development Office, Department of Agriculture, Bangkok, Thailand 10900 Email: [email protected] Summary Global invasive plant may invade in some countries, but it is not invasive plant in its native country or in range of distribution. Those plants are utilized in some means, such as vegetable, fruit, ornamental plant or medicinal plant in it native country or even it was invasive plant but people learned how to manage with that plant, they can utilize it. On the contrary way, an invasive plant of any country may not be invasive in any country else. Most of the invasive plants are intentionally introduced to a country for some purpose especially for ornamental plant. Hydrocotyle umbrellata L. was introduced to Thailand as ornamental plant, the plant can grow well and with some habit of invasive plant of this plant, nowadays the plant was found in many natural areas as weed. Introduction Most of invasive plant in an area is alien plant which was introduced from different habitat within a country or other country across geographic barrier. Well development of transportation stimulates traveling and international trading which cause of increasing introduction of alien species. Some of introduced alien plants can establish and spread out if it can adapt itself to survive in the new habitat well. If the environment of new habitat is suitable for it growth, the plant may express it invasiveness and compete for space and nutrient with native plant which it may complete over native plants due to lack of it natural enemy in new habitat. -

Sydney Program Guide

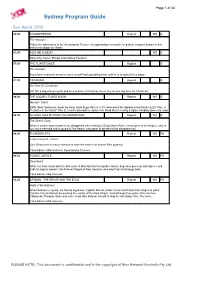

Page 1 of 34 Sydney Program Guide Sun Aug 5, 2012 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G The Imposter Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G Hosted by Lauren Phillips and Andrew Faulkner. 07:00 THE FLINTSTONES Repeat G The Gambler Psychiatric treatment seems to have cured Fred's gambling fever until he is tempted into a wager. 07:30 TAZ-MANIA Repeat G No Time For Christmas Taz fills a bag with presents and tries to deliver Christmas cheer, but no one has time for Christmas. 08:00 THE LOONEY TUNES SHOW Repeat WS G Monster Talent Daffy takes Gossamer under his wing, while Bugs stars in a TV commercial for Speedy's new frozen pizza. Plus, in "A Zipline in the Sand," Wile E. Coyote attempts to capture the Road Runner using a zipline hanging above the road. 08:30 SCOOBY DOO MYSTERY INCORPORATED Repeat WS G The Siren's Song When a sardine boat mysteriously disappears when fishing in Dead Man's Point, Velma goes to investigate, only to run into a mermaid and a couple of fish freaks, who seem to be behind the disappearings. 09:00 THUNDERCATS Repeat WS PG Trials of Lion-O - Part 2 Lion-O launches a rescue mission to save the team from Mumm-Ra's pyramid. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence, Supernatural Themes 09:30 YOUNG JUSTICE Repeat WS PG Disordered While the team deals with the aftermath of Miss Martian's telepathic attack, Superboy goes out with Sphere and finds its original owners: the Forever People of New Genesis, who want their technology back.