20070215-Bauer.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Obedience Alibi Milgram 'S Account of the Holocaust Reconsidered

David R. Mandel The Obedience Alibi Milgram 's Account of the Holocaust Reconsidered "Unable to defy the authority of the experimenter, [participantsj attribute all responsibility to him. It is the old story of 'just doing one's duty', that was heard time and again in the defence statement of the accused at Nuremberg. But it would be wrang to think of it as a thin alibi concocted for the occasion. Rather, it is a fundamental mode of thinking for a great many people once they are locked into a subordinate position in a structure of authority." {Milgram 1967, 6} Abstract: Stanley Milgram's work on obedience to authority is social psychology's most influential contribution to theorizing about Holocaust perpetration. The gist of Milgram's claims is that Holocaust perpetrators were just following orders out of a sense of obligation to their superiors. Milgram, however, never undertook a scholarly analysis of how his obedience experiments related to the Holocaust. The author first discusses the major theoretical limitations of Milgram's position and then examines the implications of Milgram's (oft-ignored) experimental manipula tions for Holocaust theorizing, contrasting a specific case of Holocaust perpetration by Reserve Police Battalion 101 of the German Order Police. lt is concluded that Milgram's empirical findings, in fact, do not support his position-one that essen tially constitutes an obedience alibi. The article ends with a discussion of some of the social dangers of the obedience alibi. 1. Nazi Germany's Solution to Their J ewish Question Like the pestilence-stricken community of Oran described in Camus's (1948) novel, The Plague, thousands ofEuropean Jewish communities were destroyed by the Nazi regime from 1933-45. -

What Do Students Know and Understand About the Holocaust? Evidence from English Secondary Schools

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Stuart Foster, Alice Pettigrew, Andy Pearce, Rebecca Hale Centre for Holocaust Education Centre Adrian Burgess, Paul Salmons, Ruth-Anne Lenga Centre for Holocaust Education What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Cover image: Photo by Olivia Hemingway, 2014 What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Stuart Foster Alice Pettigrew Andy Pearce Rebecca Hale Adrian Burgess Paul Salmons Ruth-Anne Lenga ISBN: 978-0-9933711-0-3 [email protected] British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A CIP record is available from the British Library All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permissions of the publisher. iii Contents About the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education iv Acknowledgements and authorship iv Glossary v Foreword by Sir Peter Bazalgette vi Foreword by Professor Yehuda Bauer viii Executive summary 1 Part I Introductions 5 1. Introduction 7 2. Methodology 23 Part II Conceptions and encounters 35 3. Collective conceptions of the Holocaust 37 4. Encountering representations of the Holocaust in classrooms and beyond 71 Part III Historical knowledge and understanding of the Holocaust 99 Preface 101 5. Who were the victims? 105 6. -

Yehuda Bauer

1 Shoah, Antisemitism, War, and Genocide: Text and the Context Yehuda Bauer Ladies and Gentlemen, Colleagues and Friends, The International Task Force for Holocaust Education, Remembrance, and Research, was founded by the then Swedish Prime Minister, Göran Persson, as an answer to a problem that was expected to be solved within a few years’ time, namely the lack of education. There had been worrying signs of a lack of knowledge about the Holocaust among Swedish youths, but there was also disillusionment with democracy generally. Mr. Persson’s government began the process of establishing, with government help, an independent, special, large organization called Levande Historia, to address the educational aspects of steps to be taken to remedy the situation. I was asked to advise in all this. In order to establish the ITF, the Prime Minister turned to President Clinton and Prime Minister Tony Blair to join, and they agreed. I was then asked to become the Academic Adviser of the new body and, as they say, the rest is history. Soon afterwards, Mr. Persson then suggested that a large inter-governmental conference should be organized that would address these concerns internationally, and I became the person responsible for the academic side, and a member of the organizing committee, consisting of important Swedish government officials, driven forward largely by Veronika Bard- Bringeus. We opened the Stockholm Forum on Holocaust Education on January 27, 2000, with a large number of governments in attendance. Out of that came the famous Stockholm Declaration, which until today forms the basis for the ITF. A great deal has changed since then. -

Chapter 3 the ISSUE of the HOLOCAUST AS a UNIQUE

Chapter 3 THE ISSUE OF THE HOLOCAUST AS A UNIQUE EVENT by Alan Rosenberg and Evelyn Silverman The question of the "uniqueness" of the Holocaust If the Holocaust was a truly unique event, then it has itself become a unique question. When we approach lies beyond our comprehension. If it was not the Holocaust, we are at once confronted with a truly unique, then there is no unique lesson to be dilemma: if the Holocaust is the truly unique and learned from it. Viewed solely from the unprecedented historical event that it is often held to perspective of its uniqueness, the Holocaust must be, then it must exceed the possibility of human be considered either incomprehensible or trivial. comprehension, for it lies beyond the reach of our A contexualist analysis, on the other hand, finds customary historical and sociological means of inquiry that it was neither "extra historical" nor just and understanding. But if it is not a historically unique another atrocity. It is possible to view the event, if it is simply one more incident in the long Holocaust as unprecedented in many respects history of man's inhumanity to man, there is no special and as an event of critical and transformational point in trying to understand it, no unique lesson to importance in the history of our world. Using be learned. Yehuda Bauer states the problem from a this method, we can determine the ways in which somewhat different perspective: the uniqueness question both helps and hinders our quest for understanding of the Holocaust. If what happened to the Jews was unique, then it took place outside of history, it becomes a mysterious event, an upside-down miracle, so to speak, an event of religious significance in the sense that it is not man-made as that term is normally under stood. -

Gadol Beyisrael Hagaon Hakadosh Harav Chaim Michoel Dov

Eved Hashem – Gadol BeYisrael HaGaon HaKadosh HaRav Chaim Michoel Dov Weissmandel ZTVK "L (4. Cheshvan 5664/ 25. Oktober 1903, Debrecen, Osztrák–Magyar Monarchia – 6 Kislev 5718/ 29. November 1957, Mount Kisco, New York) Евед ХаШем – Гадоль БеИсраэль ХаГаон ХаКадош ХаРав Хаим-Михаэль-Дов Вайсмандель; Klenot medzi Klal Yisroel, Veľký Muž, Bojovník, Veľký Tzaddik, vynikajúci Talmid Chacham. Takýto človek príde na svet iba raz za pár storočí. „Je to Hrdina všetkých Židovských generácií – ale aj pre každého, kto potrebuje príklad odvážneho človeka, aby sa pozrel, kedy je potrebná pomoc pre tých, ktorí sú prenasledovaní a ohrození zničením v dnešnom svete.“ HaRav Chaim Michoel Dov Weissmandel ZTVK "L, je najväčší Hrdina obdobia Holokaustu. Jeho nadľudské úsilie o záchranu tisícov ľudí od smrti, ale tiež pokúsiť sa zastaviť Holokaust v priebehu vojny predstavuje jeden z najpozoruhodnejších príkladov Židovskej histórie úplného odhodlania a obete za účelom záchrany Židov. Nesnažil sa zachrániť iba niektorých Židov, ale všetkých. Ctil a bojoval za každý Židovský život a smútil za každou dušou, ktorú nemohol zachrániť. Nadľudské úsilie Rebeho Michoela Ber Weissmandla oddialilo deportácie viac ako 30 000 Židov na Slovensku o dva roky. Zohral vedúcu úlohu pri záchrane tisícov životov v Maďarsku, keď neúnavne pracoval na zverejňovaní „Osvienčimských protokolov“ o nacistických krutostiach a genocíde, aby „prebudil“ medzinárodné spoločenstvo. V konečnom dôsledku to ukončilo deportácie v Maďarsku a ušetrilo desiatky tisíc životov maďarských Židov. Reb Michoel Ber Weissmandel bol absolútne nebojácny. Avšak, jeho nebojácnosť sa nenarodila z odvahy, ale zo strachu ... neba. Každý deň, až do svojej smrti ho ťažil smútok pre milióny, ktorí nemohli byť spasení. 1 „Prosím, seriózne študujte Tóru,“ povedal HaRav Chaim Michoel Dov Weissmandel ZTVK "L svojim študentom, "spomína Rav Spitzer. -

Professor Yehuda Bauer November 3, 2010

Professor Yehuda Bauer November 3, 2010 I want to talk briefly today about something that will arise in most classes in schools and with adult groups as well, namely a very simple question. It is clear that the Holocaust was a form of genocide; I don’t think one has to prove that. But there are other genocides that happened in the last hundred or two hundred years so why don’t we teach today about Rwanda or Darfur, or the Armenian genocide or other events of that kind, and why do we concentrate on the genocide of the Jews, which is what the Holocaust is. The term “Holocaust” simply is a special term that people use, I don’t usually use it, but I will this time. It means the genocide of the Jewish people at the hands of Nazi Germany and its allies and supporters. In order to examine what the specifics are of the genocide of the Jews I think one has to first try to understand what genocide is. I’m sure you all know that in December 1948 the United National General Assembly unanimously passed the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment for the Crime of Genocide. By now, most countries in the world have signed this Convention. The Convention is largely the product of one person, a Polish Jewish lawyer by the name of Raphael Lemkin who managed to escape to the United States from Poland via Sweden in 1941. He was later a professor at Columbia, a very unusual person who in 1933 submitted a paper to a conference of international lawyers in Madrid (he was not permitted to go there but he submitted the paper) in which he asked for an international law to prevent and punish the ultimate crime of annihilating groups of people. -

The Holocaust in Historical Perspective Yehuda Bauer

The Holocaust The Historicalin Perspective Bauer Yehuda The Holocaust in Historical The Holocaust Perspective Yehuda Bauer in Historical Between 1941 and 1945, the Nazi regime em barked on a deliberate policy of mass murder that resulted in the deaths of nearly six million Jews. What the Nazis attempted was nothing less than the total physical annihilation of the Perspective Jewish people. This unprecedented atrocity has come to be known as the Holocaust. In this series of four essays, a distinguished his torian brings the central issues of the holocaust to the attention of the general reader. The re sult is a well-informed, forceful, and eloquent work, a major contribution to Holocaust histo Yehuda Bauer riography. The first chapter traces the background of Nazi antisemitism, outlines the actual murder cam paign, and poses questions regarding the reac tion in the West, especially on the part of American Jewish leadership. The second chap ter, “Against Mystification,” analyzes the vari ous attempts to obscure what really happened. Bauer critically evaluates the work of historians or pseudohistorians who have tried to deny or explain away the Holocaust, as well as those who have attempted to turn it into a mystical experience. Chapter 3 discusses the problem of the “by stander.” Bauer examines the variety of re sponses to the Holocaust on the part of Gen tiles in Axis, occupied, Allied, and neutral lands. He attempts to establish some general (continued on back flap) The Holocaust The Historicalin Perspective Bauer Yehuda The Holocaust in Historical The Holocaust Perspective Yehuda Bauer in Historical Between 1941 and 1945, the Nazi regime em barked on a deliberate policy of mass murder that resulted in the deaths of nearly six million Jews. -

Jewish Resistance in World War II & Zionism: Making Aliyah in the Death

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2017 Jewish Resistance in World War II & Zionism: Making Aliyah in the Death Camps Cierra Tomaso Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Tomaso, Cierra, "Jewish Resistance in World War II & Zionism: Making Aliyah in the Death Camps" (2017). University Honors Program Theses. 245. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/245 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jewish Resistance in World War II & Zionism: Making Aliyah in the Death Camps An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in History. By Cierra Tomaso Under the mentorship of Dr. Brian K. Feltman ABSTRACT My thesis examines the contributions of Jewish resistance fighters in Europe during World War II. The sources used are primarily memoirs of resistance fighters, primary documents from resistance groups, and secondary articles related to Zionism during that time period. The resistance movement began because there was a need for dismantling the Third Reich from within the bounds of the ghettos, the death camps, and the killing fields. This thesis will show that Zionism played a key role in the motivations of the Jewish resistance fighters in World War II. Additionally, it will examine how as Jews found that their home countries sought to cut ties with them, they found refuge in their new identity as Zionists. -

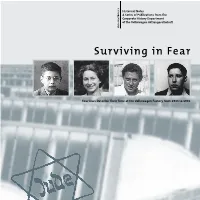

Surviving in Fear

Historical Notes A Series of Publications from the Corporate History Department of the Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft Historical Notes 3 Surviving in Fear Four Jews Describe Their Time at the Volkswagen Factory from 1943 to 1945 The authors Moshe Shen, born 1930 · Julie Nicholson, born 1922 · Sara Frenkel, born 1922 · Sally Perel, born 1925 · Susanne Urban, born 1968 Imprint Editors Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft Corporate History Department: Manfred Grieger, Ulrike Gutzmann Translation SDL Multilingual Services Design con©eptdesign, Günter Illner, Bad Arolsen Print Druckerei E. Sauerland, Langenselbold ISSN 1615-1593 ISBN 978-3-935112-22-2 © Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft Wolfsburg 2005 New edition 2013 Surviving in Fear Four Jews Describe Their Time at the Volkswagen Factory from 1943 to 1945 With a contribution by Susanne Urban Jewish Remembrance. Jewish Forced Labourers and Jews with False Papers at the Volkswagen Factory Susanne Urban _____ P. 6 Moshe Shen _____ P. 18 Julie Nicholson _____ P. 30 Jewish Remembrance. For Concentration Camp Inmates like us, Survival To Preserve History and Learn its Lessons is an Jewish Forced Labourers and Jews with False Papers was a Question of Time Essential Task at the Volkswagen Factory I. Forced labour at the Volkswagen factory Childhood and a strict father Sheltered childhood II. Structures of remembrance Too late to flee Arrested in Budapest III. Four lifelines Auschwitz Auschwitz The selection of prisoners for the Volkswagen factory Everyday life in Auschwitz Isolation and work on the “secret -

Preserved Interviews from the Claude Lanzmann Shoah Collection

Steven Spielberg Film and Video Archive Claude Lanzmann SHOAH Collection – Outtakes Available as of July 2018 Claude Lanzmann spent twelve years locating survivors, perpetrators, and eyewitnesses for his nine and a half hour film Shoah released in 1985. Without archival footage, Shoah weaves together extraordinary testimonies to render the step-by-step machinery of the destruction of European Jewry. Critics have called it "a masterpiece" and a "monument against forgetting." The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum purchased the Shoah outtakes from Lanzmann in October 1996 and have since been reconstructing and preserving the films. The Claude Lanzmann SHOAH Collection consists of roughly 185 hours of interview outtakes and 35 hours of location filming. Interviews USHMM Subject Summary Length Film ID Language Reconstruction & RG-# Preservation Completed RG- Jacob Arnon was a Dutch Jew and leader of a Zionist 2 hrs 3265 English August 2007 60.5022 student organization. Arnon’s uncle was one of the 3266 chairmen of the Jewish Council in Amsterdam, and 3267 though he admired his uncle greatly, he condemns the 3268 Council’s actions, especially their choice of whom to 3269 deport. Arnon’s uncle survived the war but the two never spoke again. RG- Ehud Avriel was born in Vienna and became active in 2.4 hrs 3100 French November 2004 60.5000 escape and rescue operations after the Anschluss. He 3101 continued this work once he reached Palestine in 1940. 3102 Avriel later held several positions in the Israeli 3103 government. 3104 RG- Bedrich Bass discusses the present-day Jewish 47 mins 3888 French December 2017 60.5084 community in Czechoslovakia and the cost of 3889 December 2016 maintaining the old Jewish cemetery in Prague. -

Zionism from Lack of Choice Yehuda Bauer

Zionism from lack of Choice Yehuda Bauer Of close to 300,000 Jews in the DP camps and in Central Europe in 1947/8, roughly two-thirds ultimately arrived in Israel; one-third went to the US, Latin America and elsewhere. Zionist leaders such as Ben-Gurion, Tabenkin, Yachil, Ya’ari and many others expressed great fears between 1946 and 1948 that the survivors would undergo two parallel processes; demoralization and dispersion in the Diaspora. There were good reasons for these apprehensions: the survivors’ stay in DP camps, where they were kept and fed but where only a few were able to find work, caused a deepening process of demoralization, which expressed itself in black marketeering, escapism and increasing cynicism. There was what one might call a large hard core of idealistic Zionists, especially youth, who fought against these phenomena, but the prolonged stay in the camps from 1948/9 deepened the crisis. On the other hand, there was a clear tendency of many to seek a personal solution in the West, especially in the United States. The rationalization was that many had suffered too much to want to undergo the further troubles expected in a Jewish Palestine struggling for independence through war and economic dislocation. There appeared a dichotomy clearly observed for instance by the members of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry early in 1946, between the overt pro-Zionist enthusiasm on the one hand, and the quiet preparation for a westward emigration on the other hand. This process affected the leadership of the She’arit Hapleta no less and perhaps more than the rank and file. -

A Curriculum Guide for Grades 9–12

VOLUME II A Curriculum Guide for Grades 9–12 New Jersey Commission on Holocaust Education 2003 Nathan Rapoport, Warsaw Ghetto Uprising THE HOLOCAUST AND GENOCIDE: THE BETRAYAL OF HUMANITY A Curriculum Guide for Grades 9–12 New Jersey Commission on Holocaust Education 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTSiI - TABLE volume TABLE OF CONTENTS UNIT V: RESISTANCE, INTERVENTION AND RESCUE . 583 I Introduction. 585 I Unit Goal, Performance Objectives, Teaching/Learning Strategies and Activities, and Instructional Materials/Resources . 587 I Readings Included in This Unit (list). 628 I Quotation from the Diary of Hannah Senesh. 631 I Reprints of Readings . 632 UNIT VI: GENOCIDE . 729 I Introduction. 731 I Unit Goal, Performance Objectives, Teaching/Learning Strategies and Activities, and Instructional Materials/Resources . 733 I Readings Included in This Unit (list). 756 I Reprints of Readings . 758 UNIT VII: ISSUES OF CONSCIENCE AND MORAL RESPONSIBILITY . 837 I Introduction. 839 I Unit Goal, Performance Objectives, Teaching/Learning Strategies and Activities, and Instructional Materials/Resources . 842 I Readings Included in This Unit (list). 887 I Reprints of Readings . 890 APPENDICES. 1015 A New Jersey Legislation Mandating Holocaust Education. 1015 B Holocaust Memorial Address by Governor James E. McGreevey . 1016 C Holocaust Timeline . 1017 D Glossary . 1020 E Holocaust Statistics . 1027 F (Part I) The Holocaust: A Web Site Directory . 1029 F (Part II) Internet Sites . 1049 G New Jersey Holocaust Resource Centers and Demonstration Sites . 1061 H Resource Organizations, Museums and Memorials . 1065 I Oral History Interview Guidelines (U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum). 1068 J Child Survivor: Suggested Interview Questions . 1090 K List of Vendors . 1098 UNIT V RESISTANCE, INTERVENTION AND RESCUE “MORDECAI ANIELEWICZ” Unit V UNIT V: RESISTANCE, INTERVENTION AND RESCUE uring the Holocaust, thousands of individuals risked their lives to protect, hide or Drescue Jews from Nazi terror.