Suitors and Suppliants the Little Nations at Versailles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African American Soldiers in the Philippine War: An

AFRIC AN AMERICAN SOLDIERS IN THE PHILIPPINE WAR: AN EXAMINATION OF THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF BUFFALO SOLDIERS DURING THE SPANISH AMERICAN WAR AND ITS AFTERMATH, 1898-1902 Christopher M. Redgraves Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2017 APPROVED: Geoffrey D. W. Wawro, Major Professor Richard Lowe, Committee Member G. L. Seligmann, Jr., Committee Member Richard G. Vedder, Committee Member Jennifer Jensen Wallach, Committee Member Harold Tanner, Chair of the Department of History David Holdeman, Dean of College of Arts and Sciences Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Redgraves, Christopher M. African American Soldiers in the Philippine War: An Examination of the Contributions of Buffalo Soldiers during the Spanish American War and Its Aftermath, 1898–1902. Doctor of Philosophy (History), August 2017, 294 pp., 8 tables, bibliography, 120 titles. During the Philippine War, 1899 – 1902, America attempted to quell an uprising from the Filipino people. Four regular army regiments of black soldiers, the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry, and the Twenty-Fourth and Twenty-Fifth Infantry served in this conflict. Alongside the regular army regiments, two volunteer regiments of black soldiers, the Forty-Eighth and Forty-Ninth, also served. During and after the war these regiments received little attention from the press, public, or even historians. These black regiments served in a variety of duties in the Philippines, primarily these regiments served on the islands of Luzon and Samar. The main role of these regiments focused on garrisoning sections of the Philippines and helping to end the insurrection. To carry out this mission, the regiments undertook a variety of duties including scouting, fighting insurgents and ladrones (bandits), creating local civil governments, and improving infrastructure. -

![Stephen Bonsal Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6761/stephen-bonsal-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-rendered-806761.webp)

Stephen Bonsal Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered

Stephen Bonsal Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2009 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms012117 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm75013193 Prepared by Lee Theisen Collection Summary Title: Stephen Bonsal Papers Span Dates: 1890-1973 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1900-1947) ID No.: MSS13193 Creator: Bonsal, Stephen, 1865-1951 Extent: 4,500 items ; 39 containers ; 16.8 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Journalist and foreign correspondent. Correspondence, diaries, writings, and other material relating chiefly to Bonsal's career as a journalist and as foreign correspondent for the New York Herald and New York Times. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Adams, James Truslow, 1878-1949--Correspondence. Baker, Newton Diehl, 1871-1937--Correspondence. Baruch, Bernard M. (Bernard Mannes), 1870-1965--Correspondence. Bismarck, Otto, Fürst von, 1815-1898. Bonsal, Stephen, 1865-1951. Clemenceau, Georges, 1841-1929. Douglas, James Stuart, 1868-1949--Correspondence. Díaz, Porfirio, 1830-1915. Frazier, Arthur Hugh, 1868- --Correspondence. Gibson, Hugh, 1883-1954--Correspondence. Harrison, Francis Burton, 1873-1957--Correspondence. House, Edward Mandell, 1858-1938--Correspondence. House, Edward Mandell, 1858-1938. Roosevelt, Franklin D. (Franklin Delano), 1882-1945. -

Ever Faithful

Ever Faithful Ever Faithful Race, Loyalty, and the Ends of Empire in Spanish Cuba David Sartorius Duke University Press • Durham and London • 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Tyeset in Minion Pro by Westchester Publishing Services. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Sartorius, David A. Ever faithful : race, loyalty, and the ends of empire in Spanish Cuba / David Sartorius. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 8223- 5579- 3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978- 0- 8223- 5593- 9 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Blacks— Race identity— Cuba—History—19th century. 2. Cuba— Race relations— History—19th century. 3. Spain— Colonies—America— Administration—History—19th century. I. Title. F1789.N3S27 2013 305.80097291—dc23 2013025534 contents Preface • vii A c k n o w l e d g m e n t s • xv Introduction A Faithful Account of Colonial Racial Politics • 1 one Belonging to an Empire • 21 Race and Rights two Suspicious Affi nities • 52 Loyal Subjectivity and the Paternalist Public three Th e Will to Freedom • 94 Spanish Allegiances in the Ten Years’ War four Publicizing Loyalty • 128 Race and the Post- Zanjón Public Sphere five “Long Live Spain! Death to Autonomy!” • 158 Liberalism and Slave Emancipation six Th e Price of Integrity • 187 Limited Loyalties in Revolution Conclusion Subject Citizens and the Tragedy of Loyalty • 217 Notes • 227 Bibliography • 271 Index • 305 preface To visit the Palace of the Captain General on Havana’s Plaza de Armas today is to witness the most prominent stone- and mortar monument to the endur- ing history of Spanish colonial rule in Cuba. -

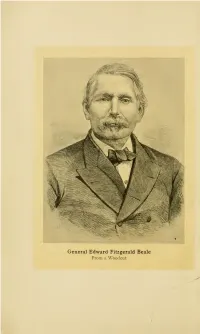

Edward Fitzgerald Beale from a Woodcut Edward Fitzgerald Beale

General Edward Fitzgerald Beale From a Woodcut Edward Fitzgerald Beale A Pioneer in the Path of Empire 1822-1903 By Stephen Bonsai With 17 Illustrations G. P. Putnam's Sons New York and London Ube ftnicfterbocfter press 1912 r6n5 Copyright, iqi2 BY TRUXTUN BEALE Ube finickerbocher pteee, 'Mew ]|?ocft £CI.A;n41 4S INTRODUCTORY NOTE EDWARD FITZGERALD BEALE, whose life is outlined in the following pages, was a remarkable man of a type we shall never see in America again. A grandson of the gallant Truxtun, Beale was bom in the Navy and his early life was passed at sea. However, he fought with the army at San Pasqual and when night fell upon that indecisive battlefield, with Kit Carson and an anonymous Indian, by a daring journey through a hostile country, he brought to Commodore Stockton in San Diego, the news of General Kearny's desperate situation. Beale brought the first gold East, and was truly, in those stirring days, what his friend and fellow- traveller Bayard Taylor called him, "a pioneer in the path of empire." Resigning from the Navy, Beale explored the desert trails and the moimtain passes which led overland to the Pacific, and later he surveyed the routes and built the wagon roads over which the mighty migration passed to people the new world beyond the Rockies. As Superintendent of the Indians, a thankless office which he filled for three years, Beale initiated a policy of honest dealing with the nation's wards iv Introductory Note which would have been even more successful than it was had cordial unfaltering support always been forthcoming from Washington. -

Balkan Reader

Stephen Bonsal, Leon Dennon, Henry Pozzi: Balkan Reader First-hand reports by Western correspondents and diplomats for over a century Edited by Andrew L. Simon Copyright © 2000 by Andrew L. Simon Library of Congress Card Number: 00-110527 ISBN: 1-931313-00-8 Distributed by Ingram Book Company Printed by Lightning Source, La Vergne, TN Published by Simon Publications, P.O. Box 321, Safety Harbor, FL Contents Introduction 1 The Authors 5 Bulgaria Stephen Bonsal; 1890: 11 Leon Dennen; 1945: 64 Yugoslavia Stephen Bonsal; 1890: 105 Stephen Bonsal; 1920: 147 John F. Montgomery; 1947: 177 Henry Pozzi; 1935: 193 Ultimatum to Serbia: 224 Leon Dennen; 1945: 229 Romania Stephen Bonsal; 1920: 253 Harry Hill Bandholtz; 1919: 261 Leon Dennen; 1945: 268 Macedonia and Albania Stephen Bonsal; 1890: 283 Henry Pozzi; 1935: 315 Appendix Repington; 1923: 333 Introduction About 100 years ago, the Senator from Minnesota, Cushman Davis in- quired from Stephen Bonsal, foreign correspondent of the New York Her- ald: “Why do not the people of Macedonia and of the Balkans generally, leave off killing one another, burning down each others’ houses, and do what is right?” “Unfortunately”, Bonsal replied, “they are convinced that they are doing what is right. The blows they strike they believe are struck in the most righ- teous of causes. If they could only be inoculated with the virus of modern skepticism and leave off doing right so fervently, there might come about an era of peace in the Balkans—and certainly the population would in- crease. As full warrant and justification of their merciless warfare, the Christians point to Jushua the Conqueror of the land of Canaan, the Turks to Mahomet. -

Convert Finding Aid To

Morris Leopold Ernst: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Ernst, Morris Leopold, 1888-1976 Title: Morris Leopold Ernst Papers Dates: 1904-2000, undated Extent: 590 boxes (260.93 linear feet), 47 galley folders (gf), 30 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: The career and personal life of American attorney and author Morris L. Ernst are documented from 1904 to 2000 through correspondence and memoranda; research materials and notes; minutes, reports, briefs, and other legal documents; handwritten and typed manuscripts; galley proofs; clippings; scrapbooks; audio recordings; photographs; and ephemera. The papers chiefly reflect the variety of issues Ernst dealt with professionally, notably regarding literary censorship and obscenity, but also civil liberties and free speech; privacy; birth control; unions and organized labor; copyright, libel, and slander; big business and monopolies; postal rates; literacy; and many other topics. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-1331 Language: English Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provided funds for the preservation and cataloging of this collection. Access: Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition: Gifts and purchases, 1961-2010 (R549, R1916, R1917, R1918, R1919, R1920, R3287, R6041, G1431, 09-06-0006-G, 10-10-0008-G) Processed by: Nicole Davis, Elizabeth Garver, Jennifer Hecker, and Alex Jasinski, with assistance from Kelsey Handler and Molly Odintz, 2009-2012 Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Ernst, Morris Leopold, 1888-1976 Manuscript Collection MS-1331 Biographical Sketch One of the most influential civil liberties lawyers of the twentieth century, Morris Ernst championed cases that expanded Americans' rights to privacy and freedom from censorship. -

PULITZER PRIZE WINNERS in LETTERS © by Larry James

PULITZER PRIZE WINNERS IN LETTERS © by Larry James Gianakos Fiction 1917 no award *1918 Ernest Poole, His Family (Macmillan Co.; 320 pgs.; bound in blue cloth boards, gilt stamped on front cover and spine; full [embracing front panel, spine, and back panel] jacket illustration depicting New York City buildings by E. C.Caswell); published May 16, 1917; $1.50; three copies, two with the stunning dust jacket, now almost exotic in its rarity, with the front flap reading: “Just as THE HARBOR was the story of a constantly changing life out upon the fringe of the city, along its wharves, among its ships, so the story of Roger Gale’s family pictures the growth of a generation out of the embers of the old in the ceaselessly changing heart of New York. How Roger’s three daughters grew into the maturity of their several lives, each one so different, Mr. Poole tells with strong and compelling beauty, touching with deep, whole-hearted conviction some of the most vital problems of our modern way of living!the home, motherhood, children, the school; all of them seen through the realization, which Roger’s dying wife made clear to him, that whatever life may bring, ‘we will live on in our children’s lives.’ The old Gale house down-town is a little fragment of a past generation existing somehow beneath the towering apartments and office-buildings of the altered city. Roger will be remembered when other figures in modern literature have been forgotten, gazing out of his window at the lights of some near-by dwelling lifting high above his home, thinking -

Pulitzer Prize Winners and Finalists

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

YOKELLIV-DISSERTATION-2018.Pdf (1.292Mb)

GERMANY AND LATIN AMERICA – DEVELOPING INFRASTRUCTURE AND FOREIGN POLICY, 1871-1914 A Dissertation by MARSHALL A. YOKELL, IV Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Adam R. Seipp Committee Members, Jason C. Parker Brian J. Rouleau Shona N. Jackson Head of Department, David Vaught December 2018 Major Subject: History Copyright 2018 Marshall Allison Yokell, IV ABSTRACT From the formation of the German nation in 1871 until the eve of World War I, Germany’s emergence on the world stage as a global power was never a simple endeavor nor one where there was a clear path forward for policymakers in Berlin or diplomats serving abroad. While scholars have focused on the direct actions in creating a formal German empire, a clear mark of a global power, they have not fully engaged in examining the impact of indirect forms of imperialism and empire building. This dissertation is a global study of German interactions in South America, and how it relied on its diplomats there to assist in the construction of an informal empire, thus demonstrating Germany’s global presence. This coterie of diplomats and foreign policy officials in Berlin pointed to South America as a region of untapped potential for Germany to establish its global footprint and become a world power. This work draws upon primary sources, both unpublished and published, examining the records of diplomats, businessmen, and colonial and religious groups to show the vast networks and intersections that influenced German policy in South America as it sought to increase its global presence and construct an informal empire. -

Pulitzer Prize Winners Biography Or Autobiography Year Winner 1917

A Monthly Newsletter of Ibadan Book Club – December Edition www.ibadanbookclub.webs.com, www.ibadanbookclub.wordpress.com E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] Pulitzer Prize Winners Biography or Autobiography Year Winner 1917 Julia Ward Howe, Laura E. Richards and Maude Howe Elliott assisted by Florence Howe Hall 1918 Benjamin Franklin, Self-Revealed, William Cabell Bruce 1919 The Education of Henry Adams, Henry Adams 1920 The Life of John Marshall, Albert J. Beveridge 1921 The Americanization of Edward Bok, Edward Bok 1922 A Daughter of the Middle Border, Hamlin Garland 1923 The Life and Letters of Walter H. Page, Burton J. Hendrick 1924 From Immigrant to Inventor, Michael Idvorsky Pupin 1925 Barrett Wendell and His Letters, M.A. DeWolfe Howe 1926 The Life of Sir William Osler, Harvey Cushing 1927 Whitman, Emory Holloway 1928 The American Orchestra and Theodore Thomas, Charles Edward Russell 1929 The Training of an American: The Earlier Life and Letters of Walter H. Page, Burton J. Hendrick 1930 The Raven, Marquis James 1931 Charles W. Eliot, Henry James 1932 Theodore Roosevelt, Henry F. Pringle 1933 Grover Cleveland, Allan Nevins 1934 John Hay, Tyler Dennett 1935 R.E. Lee, Douglas S. Freeman 1936 The Thought and Character of William James, Ralph Barton Perry 1937 Hamilton Fish, Allan Nevins 1938 Pedlar's Progress, Odell Shepard, Andrew Jackson, Marquis James 1939 Benjamin Franklin, Carl Van Doren 1940 Woodrow Wilson, Life and Letters, Vol. VII and VIII, Ray Stannard Baker 1941 Jonathan Edwards, Ola Elizabeth Winslow 1942 Crusader in Crinoline, Forrest Wilson 1943 Admiral of the Ocean Sea, Samuel Eliot Morison 1944 The American Leonardo: The Life of Samuel F.B. -

Norman Cousins Papers, 1924-1991, Bulk 1944-1990

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft558004w3 No online items Finding Aid for the Norman Cousins papers, 1924-1991, bulk 1944-1990 Processed by Manuscripts Division staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Norman 1385 1 Cousins papers, 1924-1991, bulk 1944-1990 Finding Aid for the Norman Cousins Papers, 1924-1991, bulk 1944-1990 Collection number: 1385 UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Los Angeles, CA Contact Information Manuscripts Division UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Telephone: 310/825-4988 (10:00 a.m. - 4:45 p.m., Pacific Time) Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ Processed by: Manuscripts Division staff Encoded by: Caroline Cubé Text converted and initial container list EAD tagging in part by: Apex Data Services © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Norman Cousins papers, Date (inclusive): 1924-1991, bulk 1944-1990 Collection number: 1385 Creator: Cousins, Norman. Extent: 1816 boxes (908 linear ft.) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. -

Van Loon: Popular Historian, Journalist, and Fdr

Notes ABBREVIATIONS USED IN NOTES AMBZ Archief Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken COL Columbia University, Butler Library COR Cornell University, Carl A. Kroch Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections EBvL Eliza Bowditch van Loon EBvLP Eliza Bowditch van Loon Papers ER Eleanor Roosevelt ERP Eleanor Roosevelt Papers FBI U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation FDR Franklin Delano Roosevelt FDRL Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum GAR Gemeentearchief Rotterdam GWvL Gerard Willem van Loon HAL Holland-America Line HHPL Herber Hoover Presidential Library HU Harvard University, Houghton Library HWvL Hendrik Willem van Loon HWvLP Hendrik Willem van Loon Papers KHA Koninklijk Huisarchief, Archief Prinses Juliana LC Library of Congress, Manuscript Division NA Nationaal Archief, Tweede Afdeling NIOD Nederlands Instituut voor Oorlogsdocumentatie NLMD Nederlands Letterkundig Museum en Documentatiecentrum NYPL New York Public Library, Manuscripts and Archives Division PPF President’s Personal File, Franklin D. Roosevelt Papers PSF President’s Secretary’s File, Franklin D. Roosevelt Papers SHSW State Historical Society of Wisconsin Story GWvL, The Story of Hendrik Willem van Loon (Philadelphia and New York: Lippincott Company, 1972) SUL Syracuse University Library, Department of Special Collections UIL University of Iowa Libraries, Special Collections Department UP University of Pennsylvania, Van Pelt Library, Special Collections Department ZA Zeeuws Archief 270 Notes Prologue 1. “Van Loon Buried in Old Greenwich,” New York Times, 15 March 1944; “Van Loon Rites Conducted in Old Greenwich,” New York Herald Tribune, 15 March 1944; “Van Loon Rites Attended By La Guardia, Dutch Envoy,” Greenwich Time, 15 March 1944; Unitarian Church of All Souls Archives, Rev. Laurance I. Neale Collection, HWvL Files, Text spoken by Rev.