Maq Yorkshire FINIE!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6' POLICY RESEARCH WORKING PAPER 1515 Public Disclosure Authorized

Wes 6' POLICY RESEARCH WORKING PAPER 1515 Public Disclosure Authorized Indonesia's labor market in Indonesia the I 990s is characterized by rising labor costs, reduced Labor Market Policies and worker productivity,and increasingindustrial unrest. Public Disclosure Authorized International Competitiveness The main problem is generous, centrally Nisha Agrawal mandated, but unenforceable worker benefits. Legislation encouraging enterprise-level collective bargaining might help reduce some of the costs associated with worker unrest. Public Disclosure Authorized Bacground paper for World Development Report 1995 Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Office of the Vice President Development Economics September 1995 POIjCY RESEARCH WORKING PAPER 15 15 Summary findings Indonesia's labor market in the 1990s is characterized by would be a hefty 12 percent of the wage bill. The other rising labor costs, reduced worker productivity, and problem is that the government has greatlv limited increasing industrial unrest. The main problem is organized labor, viewing it as a threat to political and generous, centrally mandated, but unenforceable worker economic stability. benefits. Legislation encouraging enterprise-level This approach of mandating benefits centrally through collective bargaining might help reduce some of the costs legislation without empowerinig workers to enforce associated with worker unrest. compliance with the legislation (or negotiate their own Policy measures Indonesia adopted in 1986 led to a benefits packages with employers) -

Political Power of Nuisance Law: Labor Picketing and the Courts In

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Faculty Scholarship 1998 Political Power of Nuisance Law: Labor Picketing and the Courts in Modern England, 1871-Present, The Rachel Vorspan Fordham University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Rachel Vorspan, Political Power of Nuisance Law: Labor Picketing and the Courts in Modern England, 1871-Present, The , 46 Buff. L. Rev. 593 (1998) Available at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship/344 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUFFALO LAW REVIEW VOLUME 46 FALL 1998 NUMBER 3 The Political Power of Nuisance Law: Labor Picketing and the Courts in Modern England, 1871-Present RACHEL VORSPANt INTRODUCTION After decades of decline, the labor movements in America and England are enjoying a resurgence. Unions in the United States are experiencing greater vitality and political visibility,' and in 1997 a Labour government took power in England for the first time in eighteen years.! This t Associate Professor of Law, Fordham University. A.B., 1967, University of California, Berkeley; M.A., 1968, Ph.D., 1975, Columbia University (English History); J.D., 1979, Harvard Law School. -

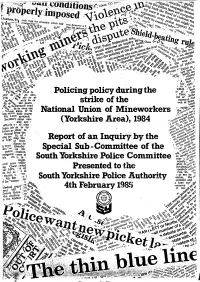

Policing-Policy-During-Strike-Report

' The Police Committee Special Sub-Committee at their meeting on 24 January 19.85 approved this report and recommended that it should be presented to the Police Committee for their approval. In doing so, they wish to place on record their appreciation and gratitude to all the members of the County Council's Department of Administration who have assisted and advised the Sub-Committee in their inquiry or who have been involved in the preparation of this report, in particular Anne Conaty (Assistant Solicitor), Len Cooksey (Committee Administrator), Elizabeth Griffiths (Secretary to the Deputy County Clerk) and David Hainsworth (Deputy County Clerk). (Councillor Dawson reserved his position on the report and the Sub-Committee agreed to consider a minority report from him). ----------------------- ~~- -1- • Frontispiece "There were many lessons to be learned from the steel strike and from the Police point of view the most valuable lesson was that to be derived from maintaining traditional Police methods of being firm but fair and resorting to minimum force by way of bodily contact and avoiding the use of weapons. My feelings on Police strategy in industrial disputes and also those of one of my predecessors, Sir Philip Knights, are encapsulated in our replies to questions asked of us when we appeared before the House of Commons Select Committee on Employment on Wednesday 27 February 1980. I said 'I would hope that despite all the problems that we have you will still allow us to have our discretion and you will not move towards the Army, CRS-type policing, or anything like that. -

Gray, Neil (2015) Neoliberal Urbanism and Spatial Composition in Recessionary Glasgow

Gray, Neil (2015) Neoliberal urbanism and spatial composition in recessionary Glasgow. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/6833/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Neoliberal Urbanism and Spatial Composition in Recessionary Glasgow Neil Gray MRes Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Geographical and Earth Sciences College of Science and Engineering University of Glasgow November 2015 i Abstract This thesis argues that urbanisation has become increasingly central to capital accumulation strategies, and that a politics of space - commensurate with a material conjuncture increasingly subsumed by rentier capitalism - is thus necessarily required. The central research question concerns whether urbanisation represents a general tendency that might provide an immanent dialectical basis for a new spatial politics. I deploy the concept of class composition to address this question. In Italian Autonomist Marxism (AM), class composition is understood as the conceptual and material relation between ‘technical’ and ‘political’ composition: ‘technical composition’ refers to organised capitalist production, capital’s plans as it were; ‘political composition’ refers to the degree to which collective political organisation forms a basis for counter-power. -

Collective Bargaining Provisions : Strikes and Lock-Outs, Contract

COLLECTIVE BARGAINING PROVISIONS Strikes and Lock-Outs; Contract Enforcement Bulletin No. 908-13 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF LABOR Maurice J. Tobin, Secretary BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS Ewan Clague, Commissioner Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Letter of Transmittal United States Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Washington, D. C., November 15,19Jk9, The Secretary of Labor: I have the honor to transmit herewith the thirteenth bulletin in the series on collective bargaining provisions. The bulletin consists of two chapters: (1) Strikes and Lockouts, and (2) Contract Enforcement, and is based on an examination of collective bargaining agreements on file in the Bureau. Both chapters were prepared in the Bureau’s Division of Industrial Relations, by and under the direction of Abraham Weiss, and by James C. Nix. Ew an Clague, Commissioner. Hon. Maurice J. Tobin, Secretary of Labor. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. Price 25 cents Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Preface As early as 1902 the Bureau of Labor Statistics, then the Bureau of Labor in the Department of the Interior, recognized the grow ing importance of collective bargaining, and published verbatim the bituminous-coal mining agreement of 1902 between the Asso ciations of Coal Mine Operators of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois and the respective districts of the United Mine Workers of America. Since 1912 the Bureau has made a systematic effort to collect agreements between labor and management in the lead ing industries and has from time to time published some of those agreements in full or in summary form in the Monthly Labor Review. -

![[I] NORTH of ENGLAND INSTITUTE of MINING and MECHANICAL](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2457/i-north-of-england-institute-of-mining-and-mechanical-712457.webp)

[I] NORTH of ENGLAND INSTITUTE of MINING and MECHANICAL

[i] NORTH OF ENGLAND INSTITUTE OF MINING AND MECHANICAL ENGINEERS. TRANSACTIONS. VOL. XXI. 1871-72. NEWCASTLE-UPON-TYNE: A. REID, PRINTING COURT BUILDINGS, AKENSIDE HILL. 1872. [ii] Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Andrew Reid, Printing Court Buildings, Akenside Hill. [iii] CONTENTS OF VOL. XXI. Page. Report of Council............... v Finance Report.................. vii Account of Subscriptions ... viii Treasurer's Account ......... x General Account ............... xii Patrons ............................. xiii Honorary and Life Members .... xiv Officers, 1872-73 .................. xv Members.............................. xvi Students ........................... xxxiv Subscribing Collieries ...... xxxvii Rules ................................. xxxviii Barometer Readings. Appendix I.......... End of Vol Patents. Appendix II.......... End of Vol Address by the Dean of Durham on the Inauguration of the College of Physical Science .... End of Vol Index ....................... End of Vol GENERAL MEETINGS. 1871. page. Sept. 2.—Election of Members, &c 1 Oct. 7.—Paper by Mr. Henry Lewis "On the Method of Working Coal by Longwall, at Annesley Colliery, Nottingham" 3 Discussion on Mr. Smyth's Paper "On the Boring of Pit Shafts in Belgium... ... ... ... ... ... ... .9 Paper "On the Education of the Mining Engineer", by Mr. John Young ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 21 Discussed ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 32 Dec. 2.—Paper by Mr. Emerson Bainbridge "On the Difference between the Statical and Dynamical Pressure of Water Columns in Lifting Sets" 49 Paper "On the Cornish Pumping Engine at Settlingstones" by Mr. F.W. Hall ... 59 Report upon Experiments of Rivetting with Drilled and Punched Holes, and Hand and Power Rivetting 67 1872 Feb. 3.—Paper by Mr. W. N. Taylor "On Air Compressing Machinery as applied to Underground Haulage, &c, at Ryhope Colliery" .. 73 Discussed ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 80 Alteration of Rule IV. ... .. ... 82 Mar. -

WORKING AGREEMENT Between and CEMENT MASONS INTERNATIONAL O. P. & C. M. I. a LOCAL UNION NO. 692 (Area 532) INDIANAPOLIS

WORKING AGREEMENT Between _________________________________________________ And CEMENT MASONS INTERNATIONAL O. P. & C. M. I. A LOCAL UNION NO. 692 (Area 532) INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA INDEX Article I - Purpose 1 Article II - Recognition 1 Article III - Subcontracting 1 Article IV - Duration and Amendment 1,2 Article V - Scope of Agreement 2 Article VI - Craft Jurisdiction (See Appendix A) 2 Article VII - Jurisdictional Disputes 2 Article VIII - No Strike/No Lockout 3 Article IX - Union Security/Check Off 3-4 Article X - Management Rights 4,5 Article XI - Pre-Job Conference 5 Article XII - Hours and Working Conditions 5,6 - Multiple Shifts 6 - Holidays 6,7 - Overtime 7 - Reporting Time/Pay Procedure 7-8 Article XIII - Steward 8 Article XIV - General Working Conditions 8-10 Article XV - Grievance/Arbitration 10,11 Article XVI - Special Provisions 12 i Article XVII - Safety/Job Facilities/Substance Abuse Policy 12,13 Article XVIII - Non Discrimination 13,14 Article XIX - Classification 14 Article XX - Wages 14 Article XXI - Savings Clause 15 Article XXII - Construction Industry Progress Council 15 Article XXIII - Apprenticeship 15,16 Article XXIV - Health & Welfare 17,18 Article XXV - Pension 18,19 Article XXVI - All Benefits 19 Appendix "A" - Craft Jurisdiction 19-22 Union and Employer Signature Page 23 ii WORKING AGREEMENT Between ___________________________________________________ and CEMENT MASONS INTERNATIONAL O. P. & C. M. I. A. LOCAL UNION NO. 692 (Area 532) INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA THIS AGREEMENT made this 01 day of June 2008, by and between _____________________________________ designated as the "Employer" and Cement Masons International 0.P.&C.M.I.A. Local Union No. 692 (Area 532), Indianapolis, Indiana, hereinafter in this Agreement designated as the "Union." - being duly constituted, authorized and recognized bargaining representative for and on behalf of the Cement Mason employees of the Employer. -

Labour Relations Code

Province of Alberta LABOUR RELATIONS CODE Revised Statutes of Alberta 2000 Chapter L-1 Current as of February 10, 2021 Office Consolidation © Published by Alberta Queen’s Printer Alberta Queen’s Printer Suite 700, Park Plaza 10611 - 98 Avenue Edmonton, AB T5K 2P7 Phone: 780-427-4952 Fax: 780-452-0668 E-mail: [email protected] Shop on-line at www.qp.alberta.ca Copyright and Permission Statement Alberta Queen's Printer holds copyright on behalf of the Government of Alberta in right of Her Majesty the Queen for all Government of Alberta legislation. Alberta Queen's Printer permits any person to reproduce Alberta’s statutes and regulations without seeking permission and without charge, provided due diligence is exercised to ensure the accuracy of the materials produced, and Crown copyright is acknowledged in the following format: © Alberta Queen's Printer, 20__.* *The year of first publication of the legal materials is to be completed. Note All persons making use of this consolidation are reminded that it has no legislative sanction, that amendments have been embodied for convenience of reference only. The official Statutes and Regulations should be consulted for all purposes of interpreting and applying the law. Amendments Not in Force This consolidation incorporates only those amendments in force on the consolidation date shown on the cover. It does not include the following amendments: 2018 c21 s6 amends ss73(a.1), 74(a.1), 95.2(1), 96(1), adds s209. 2020 c28 s11 amends s26, adds s24.1 and 26.1, amends ss27, 28, 29(2), 149 and 151. -

South Yorkshire

INDUSTRIAL HISTORY of SOUTH RKSHI E Association for Industrial Archaeology CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 6 STEEL 26 10 TEXTILE 2 FARMING, FOOD AND The cementation process 26 Wool 53 DRINK, WOODLANDS Crucible steel 27 Cotton 54 Land drainage 4 Wire 29 Linen weaving 54 Farm Engine houses 4 The 19thC steel revolution 31 Artificial fibres 55 Corn milling 5 Alloy steels 32 Clothing 55 Water Corn Mills 5 Forging and rolling 33 11 OTHER MANUFACTUR- Windmills 6 Magnets 34 ING INDUSTRIES Steam corn mills 6 Don Valley & Sheffield maps 35 Chemicals 56 Other foods 6 South Yorkshire map 36-7 Upholstery 57 Maltings 7 7 ENGINEERING AND Tanning 57 Breweries 7 VEHICLES 38 Paper 57 Snuff 8 Engineering 38 Printing 58 Woodlands and timber 8 Ships and boats 40 12 GAS, ELECTRICITY, 3 COAL 9 Railway vehicles 40 SEWERAGE Coal settlements 14 Road vehicles 41 Gas 59 4 OTHER MINERALS AND 8 CUTLERY AND Electricity 59 MINERAL PRODUCTS 15 SILVERWARE 42 Water 60 Lime 15 Cutlery 42 Sewerage 61 Ruddle 16 Hand forges 42 13 TRANSPORT Bricks 16 Water power 43 Roads 62 Fireclay 16 Workshops 44 Canals 64 Pottery 17 Silverware 45 Tramroads 65 Glass 17 Other products 48 Railways 66 5 IRON 19 Handles and scales 48 Town Trams 68 Iron mining 19 9 EDGE TOOLS Other road transport 68 Foundries 22 Agricultural tools 49 14 MUSEUMS 69 Wrought iron and water power 23 Other Edge Tools and Files 50 Index 70 Further reading 71 USING THIS BOOK South Yorkshire has a long history of industry including water power, iron, steel, engineering, coal, textiles, and glass. -

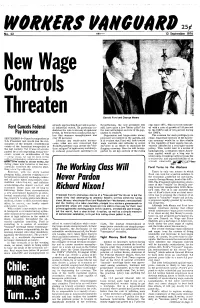

The Working Class Will

25¢ No.52 ~¢~) )(·'23 13 September 1974 ew ontrolS reaten Gerald Ford and George Meany already approaching 8 percent in sever Nevertheless, the new president will clip since 1971. This is to be contrast Ford Cancels Federal al industrial states. (In particular in still have quite a few "bitter pills" for ed with a rate of growth of 1.8 percent dustries the rate is already at epidemic the less advantaged sectors of the pop in the 1950's and of 3.5 percent during Pay Increase levels. In New Jersey construction ear ulation to swallow. the 1960's. lier this summer unemployment was Depression and large-scale uneIll The reasons for such profligacy are SEPTEMBER 9-Nixon's resignation as over 30 percent.) ployment are indeed on the agenda, and clear. Important sectors of the Ameri U.S. President last month was the cul Liberals ana trade-union bureau it is evident that Ford will look toward can economy would be in dire straits mination of the deepest constitutional crats alike are now concerned that wage controls and cutbacks in social if the liquidity of their assets was ad crisis of the American bourgeoisie in Ford/Rockefeller may invoke the "old services in an effort to stimulate the versely affected by a real tight-money the last century. Yet it was not accom time religion" of tight money and sharp flagging economy. Here he will be sup policy. This would lead to a series of panied by a corresponding social/eco ly reduced government spending in an ported by all key sectors of the ruling bankruptcies, a situation which Amer nomic crisis or m:>bilization of the ican capital would go a long way to ',',":l'k:ng C h5s. -

4.-Report-Of-South-Yorkshire-Police

' The Police Committee Special Sub-Committee at their meeting on 24 January 19.85 approved this report and recommended that it should be presented to the Police Committee for their approval. In doing so, they wish to place on record their appreciation and gratitude to all the members of the County Council's Department of Administration who have assisted and advised the Sub-Committee in their inquiry or who have been involved in the preparation of this report, in particular Anne Conaty (Assistant Solicitor), Len Cooksey (Committee Administrator), Elizabeth Griffiths (Secretary to the Deputy County Clerk) and David Hainsworth (Deputy County Clerk). (Councillor Dawson reserved his position on the report and the Sub-Committee agreed to consider a minority report from him). ----------------------- ~~- -1- • Frontispiece "There were many lessons to be learned from the steel strike and from the Police point of view the most valuable lesson was that to be derived from maintaining traditional Police methods of being firm but fair and resorting to minimum force by way of bodily contact and avoiding the use of weapons. My feelings on Police strategy in industrial disputes and also those of one of my predecessors, Sir Philip Knights, are encapsulated in our replies to questions asked of us when we appeared before the House of Commons Select Committee on Employment on Wednesday 27 February 1980. I said 'I would hope that despite all the problems that we have you will still allow us to have our discretion and you will not move towards the Army, CRS-type policing, or anything like that. -

Kiveton Park and Wales History Society Internet Copy Reproduction Prohibited

Society History Copy Wales Prohibited and Internet Park Reproduction Kiveton 2 “This is the past that’s mine.” Historical writing is a process of selection and choice as such this historical view is the information which I have selected to use; as such it does not claim to be the history of Edwardian Wales, but a history of Edwardian Wales. “This is my truth.” Society The history is written from my own broadly socialist position, and carries with it the baggage of my own social and political views both conscious and unconscious. History “Where we stand in regard to the past, what the relations are between past, present and future are not only matters of vital interest to all: they are quite indispensable. We cannot help situating ourselves in the continuum of our own life, of the family andCopy the group to which we belong. We cannot help comparing past and present: thatWales is what family photo albums or home movies are there for. We cannot help learning from it, for that is what experienceProhibited means.” Eric Hobsbawm, On History, P24 and “ The Historian is part of history. The Internetpoint in the procession at which he finds himself determines his angle of vision over the past.” Park E. H. Carr, What is History, P36 Reproduction Kiveton Paul Hanks Feb 2007 3 Society History Copy Wales © Copyright Notice Prohibited All material in this book is copyright of Paul Hanks, unless otherwise stated. This version and the designwork therein is copyright of the Kiveton Park and Wales History Society, with acknowledgement to the editorial and design contriutions of Holly Greenhalghand of Kiveton Creative and John Tanner as editor.