Rotherham Character Zone Descriptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

19 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

19 bus time schedule & line map 19 Dinnington <-> Rotherham Town Centre View In Website Mode The 19 bus line (Dinnington <-> Rotherham Town Centre) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Dinnington <-> Rotherham Town Centre: 8:45 AM (2) Rotherham Town Centre <-> Thurcroft: 8:50 AM - 4:20 PM (3) Rotherham Town Centre <-> Worksop: 6:00 AM - 7:20 PM (4) Thurcroft <-> Rotherham Town Centre: 9:18 AM - 4:48 PM (5) Worksop <-> Rotherham Town Centre: 5:20 AM - 5:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 19 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 19 bus arriving. Direction: Dinnington <-> Rotherham Town Centre 19 bus Time Schedule 47 stops Dinnington <-> Rotherham Town Centre Route VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Timetable: Sunday Not Operational Dinnington Interchange/A2, Dinnington Monday Not Operational Constable Lane, Anston Tuesday 8:45 AM Breck Lane/Outgang Lane, Dinnington Wednesday 8:45 AM Breck Lane/Anne Street, Throapham Thursday 8:45 AM St Johns Road/Kingswood Avenue, Laughton-En- Friday 8:45 AM Le-Morthen Saturday 8:45 AM St Johns Road/St Johns Court, Laughton-En-Le- Morthen School Road/High Street, Laughton-En-Le- Morthen 19 bus Info Direction: Dinnington <-> Rotherham Town Centre School Road/Castle Green, Laughton-En-Le- Stops: 47 Morthen Trip Duration: 45 min Line Summary: Dinnington Interchange/A2, Hangsman Lane/Glaisdale Close, Laughton Dinnington, Breck Lane/Outgang Lane, Dinnington, Common Breck Lane/Anne Street, Throapham, St Johns Road/Kingswood Avenue, Laughton-En-Le-Morthen, 7 Hangsman Lane, Thurcroft -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

An evaluation of river catchment quality in relation to restoration issues. AHMED, Badria S. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19204/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19204/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Return to Learning Centre of issue Fines are charged at 50p per hour 2 6 JUL J U X V U l 1 V /-L i REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10694084 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10694084 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 An Evaluation of River Catchment Quality in Relation to Restoration Issues. -

Applications and Decisions for the North East of England

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (NORTH EAST OF ENGLAND) APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 6338 PUBLICATION DATE: 10/04/2019 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 01/05/2019 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 248 8521 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Applications and Decisions will be published on: 17/04/2019 Publication Price 60 pence (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede each section, where appropriate. Accuracy of publication – Details published of applications reflect information provided by applicants. The Traffic Commissioner cannot be held responsible for applications that contain incorrect information. Our website includes details of all applications listed in this booklet. The website address is: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners Copies of Applications and Decisions can be inspected -

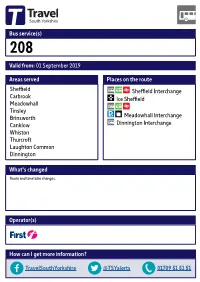

Valid From: 01 September 2019 Bus Service(S) What's Changed Areas

Bus service(s) 208 Valid from: 01 September 2019 Areas served Places on the route Sheffield Sheffield Interchange Carbrook Ice Sheffield Meadowhall Tinsley Brinsworth Meadowhall Interchange Canklow Dinnington Interchange Whiston Thurcroft Laughton Common Dinnington What’s changed Route and timetable changes. Operator(s) How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for service 208 01/02/2019 Scholes Parkgate Dalton Thrybergh Braithwell Ecclesfield Ravenfield Common Kimberworth East Dene Blackburn ! Holmes Meadowhall, Interchange Flanderwell Brinsworth, Hellaby Bonet Lane/ Bramley Wincobank Brinsworth Lane Maltby ! Longley ! Brinsworth, Meadowhall, Whiston, Worrygoose Lane/Reresby Drive ! Ñ Whitehill Lane/ Meadowhall Drive/ Hooton Levitt Bawtry Road Meadowhall Way 208 Norwood ! Thurcroft, Morthen Road/Green Lane Meadowhall, Whiston, ! Meadowhall Way/ Worrygoose Lane/ Atterclie, Vulcan Road Greystones Road Thurcroft, Katherine Road/Green Arbour Road ! Pitsmoor Atterclie Road/ Brinsworth, Staniforth Road Comprehensive School Bus Park ! Thurcroft, Katherine Road/Peter Street Laughton Common, ! ! Station Road/Hangsman Lane ! Atterclie, AtterclieDarnall Road/Shortridge Street ! ! ! Treeton Dinnington, ! ! ! Ulley ! Doe Quarry Lane/ ! ! ! Dinnington Comp School ! Sheeld, Interchange Laughton Common, Station Road/ ! 208! Rotherham Road 208 ! Aughton ! Handsworth ! 208 !! Manor !! Dinnington, Interchange Richmond ! ! ! Aston database right 2019 Swallownest and Heeley Todwick ! Woodhouse yright p o c Intake North Anston own r C Hurlfield ! data © y Frecheville e Beighton v Sur e South Anston c ! Wales dnan ! r O ! ! ! ! Kiveton Park ! ! ! ! ! ! Sothall ontains C 2019 ! = Terminus point = Public transport = Shopping area = Bus route & stops = Rail line & station = Tram route & stop 24 hour clock 24 hour clock Throughout South Yorkshire our timetables use the 24 hour clock to avoid confusion between am and pm times. -

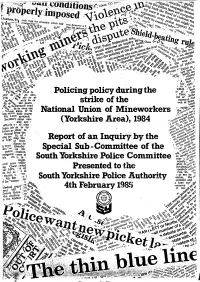

Policing-Policy-During-Strike-Report

' The Police Committee Special Sub-Committee at their meeting on 24 January 19.85 approved this report and recommended that it should be presented to the Police Committee for their approval. In doing so, they wish to place on record their appreciation and gratitude to all the members of the County Council's Department of Administration who have assisted and advised the Sub-Committee in their inquiry or who have been involved in the preparation of this report, in particular Anne Conaty (Assistant Solicitor), Len Cooksey (Committee Administrator), Elizabeth Griffiths (Secretary to the Deputy County Clerk) and David Hainsworth (Deputy County Clerk). (Councillor Dawson reserved his position on the report and the Sub-Committee agreed to consider a minority report from him). ----------------------- ~~- -1- • Frontispiece "There were many lessons to be learned from the steel strike and from the Police point of view the most valuable lesson was that to be derived from maintaining traditional Police methods of being firm but fair and resorting to minimum force by way of bodily contact and avoiding the use of weapons. My feelings on Police strategy in industrial disputes and also those of one of my predecessors, Sir Philip Knights, are encapsulated in our replies to questions asked of us when we appeared before the House of Commons Select Committee on Employment on Wednesday 27 February 1980. I said 'I would hope that despite all the problems that we have you will still allow us to have our discretion and you will not move towards the Army, CRS-type policing, or anything like that. -

Rotherham Local Plan

making sense of heritage Rotherham Local Plan Archaeology Scoping Study of Additional Site Allocations Ref: 79971.01 November 2013 Rotherham Local Plan, Archaeology Scoping Study of Additional Site Allocations Prepared for: Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council, Planning Policy – Planning & Regeneration, Environment & Development Services, Riverside House, Main Street, Rotherham, S60 1AE. Prepared by: Wessex Archaeology, Unit R6 Riverside Block, Sheaf Bank Business Park, Prospect Road, Sheffield, S2 3EN. www.wessexarch.co.uk November 2013 79971.01 © Wessex Archaeology Ltd 2013, all rights reserved Wessex Archaeology Ltd is a Registered Charity No. 287786 (England&Wales) and SC042630 (Scotland) Rotherham Local Plan Archaeology Scoping Study of Additional Site Allocations Quality Assurance Project Code 79971 Accession n/a Client n/a Code Ref. Planning n/a Ordnance Survey 446233, 391310 (centred) Application (OS) national grid Ref. reference (NGR) Version Status* Prepared by Checked and Approver’s Signature Date Approved By v01 E GC APN 18/11/13 File: S:\PROJECTS\79971 (Rotherham LDF 2)\Report\Working versions v02 F GC APN 28/11/13 File: S:\PROJECTS\79971 (Rotherham LDF 2)\Report v03 F AG AB 04/06/14 File: S:\PROJECTS\79971 (Rotherham LDF 2)\Report File: File: * I= Internal Draft; E= External Draft; F= Final DISCLAIMER THE MATERIAL CONTAINED IN THIS REPORT WAS DESIGNED AS AN INTEGRAL PART OF A REPORT TO AN INDIVIDUAL CLIENT AND WAS PREPARED SOLELY FOR THE BENEFIT OF THAT CLIENT. THE MATERIAL CONTAINED IN THIS REPORT DOES NOT NECESSARILY STAND ON ITS OWN AND IS NOT INTENDED TO NOR SHOULD IT BE RELIED UPON BY ANY THIRD PARTY. -

A Deterministic Method for Evaluating Block Stability on Masonry Spillways

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU International Symposium on Hydraulic Structures May 16th, 12:10 PM A Deterministic Method for Evaluating Block Stability on Masonry Spillways Owen John Chesterton Mott MacDonald, [email protected] John G. Heald Mott MacDonald John P. Wilson Mott MacDonald Bently John R. Foster Mott MacDonald Bently Charlie Shaw Mott MacDonald See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/ishs Recommended Citation Chesterton, Owen (2018). A Deterministic Method for Evaluating Block Stability on Masonry Spillways. Daniel Bung, Blake Tullis, 7th IAHR International Symposium on Hydraulic Structures, Aachen, Germany, 15-18 May. doi: 10.15142/T3N64T (978-0-692-13277-7). This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Symposium on Hydraulic Structures by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Author Information Owen John Chesterton, John G. Heald, John P. Wilson, John R. Foster, Charlie Shaw, and David E. Rebollo This event is available at DigitalCommons@USU: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/ishs/2018/session2-2018/2 7th International Symposium on Hydraulic Structures Aachen, Germany, 15-18 May 2018 ISBN: 978-0-692-13277-7 DOI: 10.15142/T3N64T A Deterministic Method for Evaluating Block Stability on Masonry Spillways O.J. Chesterton1, J.G. Heald1, J.P. Wilson2, J.R. Foster2, C. Shaw2 & D.E Rebollo2 1Mott MacDonald, Cambridge, United Kingdom 2Mott MacDonald Bentley, Leeds, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Many early spillways and weirs in the United Kingdom were constructed or faced with masonry. -

Green Routes - November 2015 Finkle Street Old Denaby Bromley Hoober Bank

Langsett Reservoir Newhill Bow Broom Hingcliff Hill Pilley Green Tankersley Elsecar Roman Terrace Upper Midhope Upper Tankersley SWINTON Underbank Reservoir Midhopestones Green Moor Wortley Lea Brook Swinton Bridge Midhope Reservoir Hunshelf Bank Smithy Moor Green Routes - November 2015 Finkle Street Old Denaby Bromley Hoober Bank Gosling Spring Street Horner House Low Harley Barrow Midhope Moors Piccadilly Barnside Moor Wood Willows Howbrook Harley Knoll Top Cortworth Fenny Common Ings Stocksbridge Hoober Kilnhurst Thorncliffe Park Sugden Clough Spink Hall Wood Royd Wentworth Warren Hood Hill High Green Bracken Moor Howbrook Reservoir Potter Hill East Whitwell Carr Head Whitwell Moor Hollin Busk Sandhill Royd Hooton Roberts Nether Haugh ¯ River Don Calf Carr Allman Well Hill Lane End Bolsterstone Ryecroft Charltonbrook Hesley Wood Dog Kennel Pond Bitholmes Wood B Ewden Village Morley Pond Burncross CHAPELTOWN White Carr la Broomhead Reservoir More Hall Reservoir U c Thorpe Hesley Wharncliffe Chase k p Thrybergh Wigtwizzle b Scholes p Thorpe Common Greasbrough Oaken Clough Wood Seats u e Wingfield Smithy Wood r Brighthorlmlee Wharncliffe Side n Greno Wood Whitley Keppel's Column Parkgate Aldwarke Grenoside V D Redmires Wood a Kimberworth Park Smallfield l o The Wheel l Dropping Well Northfield Dalton Foldrings e n Ecclesfield y Grange Lane Dalton Parva Oughtibridge St Ann's Eastwood Ockley Bottom Oughtibridg e Kimberworth Onesacr e Thorn Hill East Dene Agden Dalton Magna Coldwell Masbrough V Bradgate East Herringthorpe Nether Hey Shiregreen -

Laughton Parish Council Newsletter 113055.Ai

Laughton-en-le-Morthen Parish Council (Incorporating Brookhouse, Carr, Slade Hooton and Newhall Hamlet) News Update News for the Parishioners of Laughton-en-le-Morthen Parish Issue No. 35 – May 2019 Welcome to our latest news update. This newsletter is produced to keep parishioners informed about the activities being undertaken by the Parish Council for the benefit of the Parish, as well as other information on local events that you may be interested in. We hope that you find it informative. For the first time we are also including an update from Ward Councillors. We always welcome any feedback or new ideas so please get in touch with either me, or Caroline, our Parish Clerk, if there is anything you’d like to raise. Contact details are included on page 2. Parishioners are always very welcome to come along to our Parish Council meetings. Trevor Stanway Parish Council Chairman Annual Parish Meeting St Johns Road The Annual Parish Meeting is at 6.00pm on Wednesday 22nd May in the Village Hall. This meeting is held for Laughton-en-le-Morthen Allotments Open Day Parish electors. It is a statutory meeting of local government electors We are proud that there has been an allotment on St Johns Road since registered in Laughton-en-le-Morthen Parish. It is a public meeting the early 1900s and we are very happy to announce that the site is in where electors can raise questions or put forward any suggestions to the process of being rejuvenated, we now have a new meeting room, the meeting. -

IL Combo Ndx V2

file IL COMBO v2 for PDF.doc updated 13-12-2006 THE INDUSTRIAL LOCOMOTIVE The Quarterly Journal of THE INDUSTRIAL LOCOMOTIVE SOCIETY COMBINED INDEX of Volumes 1 to 7 1976 – 1996 IL No.1 to No.79 PROVISIONAL EDITION www.industrial-loco.org.uk IL COMBO v2 for PDF.doc updated 13-12-2006 INTRODUCTION and ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This “Combo Index” has been assembled by combining the contents of the separate indexes originally created, for each individual volume, over a period of almost 30 years by a number of different people each using different approaches and methods. The first three volume indexes were produced on typewriters, though subsequent issues were produced by computers, and happily digital files had been preserved for these apart from one section of one index. It has therefore been necessary to create digital versions of 3 original indexes using “Optical Character Recognition” (OCR), which has not proved easy due to the relatively poor print, and extremely small text (font) size, of some of the indexes in particular. Thus the OCR results have required extensive proof-reading. Very fortunately, a team of volunteers to assist in the project was recruited from the membership of the Society, and grateful thanks are undoubtedly due to the major players in this exercise – Paul Burkhalter, John Hill, John Hutchings, Frank Jux, John Maddox and Robin Simmonds – with a special thankyou to Russell Wear, current Editor of "IL" and Chairman of the Society, who has both helped and given encouragement to the project in a myraid of different ways. None of this would have been possible but for the efforts of those who compiled the original individual indexes – Frank Jux, Ian Lloyd, (the late) James Lowe, John Scotford, and John Wood – and to the volume index print preparers such as Roger Hateley, who set a new level of presentation which is standing the test of time. -

Rural Local Letting Policy

Rural Housing Local Letting Policy - A Rural village is a population less than 3,500; few or no facilities; surrounded by open countryside. There are 35 rural villages in Rotherham, some with populations as small as 100. However, not all villages have any council stock. In the villages listed below with Council Stock 50% of new vacancies will be offered to persons on the housing register with a local connection. The applicant will have a Local Connection if: o Their only or principle home is within the boundaries of the locality covered by the rural housing letting policy and has been for the last 12 months. o The applicant (not a member of their household) is in permanent paid work in the locality covered by the rural housing letting policy o They have a son, daughter, brother, sister, mother or father, who is over 18 and lives in the locality covered by the rural housing letting policy and has done so for at least five years before the date of application. The localities covered by the rural housing letting policy are: Rural Villages Approx Pop Council Stock Brookhouse / Slade Hooton / Carr 251 2 X HOUSES SLADE HOOTON Laughton en le Morthen 951 NO STOCK Firbeck / Stone 326 5 X HOUSES FIRBECK Letwell / Gildingwells 221 4 X HOUSES GILDINGWELLS Woodsetts 1792 47 MIXTURE OF TYPES Thorpe Salvin 437 9 X HOUSES Harthill 1688 136 MIXTURE OF TYPES Woodall 171 NO STOCK Todwick 1259 15 MIXTURE OF TYPES Hardwick 102 NO STOCK Ulley 164 10 MIXTURE OF TYPES Upper Whiston / Morthen / Guilthwaite 198 NO STOCK Scholes 339 NO STOCK Harley / Barrow / Spittal Houses / Hood Hill 864 38 MIXTURE OF TYPES HARLEY Wentworth 362 11 BUNGALOWS Hoober 173 NO STOCK Nether Haugh 104 NO STOCK Hooten Roberts 154 4 X BUNGALOWS Hooten Levitt 121 4X BUNG AND 1 HOUSE Brampton en le Morthen / Brampton 112 NO STOCK Common Treeton 2769 230 MIXTURE OF TYPES Springvale 324 NO STOCK Dalton Magna 525 NO STOCK Ravenfield 280 144 MIXTURE OF TYPES Laughton Common 1058 8 BUNGALOWS Total 14745 668 . -

All Notices Gazette

ALL NOTICES GAZETTE CONTAINING ALL NOTICES PUBLISHED ONLINE ON 3 NOVEMBER 2015 PRINTED ON 4 NOVEMBER 2015 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY | ESTABLISHED 1665 WWW.THEGAZETTE.CO.UK Contents State/2* Royal family/ Parliament & Assemblies/ Honours & Awards/ Church/3* Environment & infrastructure/4* Health & medicine/ Other Notices/8* Money/ Companies/9* People/65* Terms & Conditions/90* * Containing all notices published online on 3 November 2015 STATE STATE Departments of State CROWN OFFICE 2426643THE QUEEN has been pleased by Letters Patent under the Great Seal of the Realm dated 30 October 2015 to confer the dignity of a Barony of the United Kingdom for life upon the following: In the forenoon John Anthony Bird, Esquire, M.B.E., by the name, style and title of BARON BIRD, of Notting Hill in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. In the afternoon Dame Julia Elizabeth King, D.B.E., by the name, style and title of BARONESS BROWN OF CAMBRIDGE, of Cambridge in the County of Cambridgeshire. C .I.P . Denyer (2426643) 2426642THE QUEEN has been pleased by Letters Patent under the Great Seal of the Realm dated 29 October 2015 to confer the dignity of a Barony of the United Kingdom for life upon Robert James Mair, Esquire, C.B.E., by the name, style and title of BARON MAIR, of Cambridge in the County of Cambridgeshire. C .I.P . Denyer (2426642) THE2426062 QUEEN has been pleased by Letters Patent under the Great Seal of the Realm dated 29 October 2015 to confer the dignity of a Barony of the United Kingdom for life upon Robert James Mair, Esquire, C.B.E., by the name, style and title of BARON MAIR, of Cambridge in the County of Cambridgeshire.