Australia's Relationship with China During the Howard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copy of Financial Statements and Reports

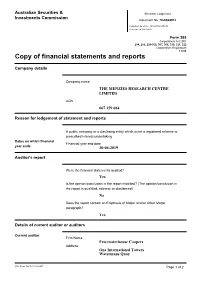

Australian Securities & Electronic Lodgement Investments Commission Document No. 7EAQ24912 Lodgement date/time: 14-10-2019 14:04:53 Reference Id: 131203477 Form 388 Corporations Act 2001 294, 295, 298-300, 307, 308, 319, 321, 322 Corporations Regulations 1.0.08 Copy of financial statements and reports Company details Company name THE MENZIES RESEARCH CENTRE LIMITED ACN 067 359 684 Reason for lodgement of statement and reports A public company or a disclosing entity which is not a registered scheme or prescribed interest undertaking Dates on which financial Financial year end date year ends 30-06-2019 Auditor's report Were the financial statements audited? Yes Is the opinion/conclusion in the report modified? (The opinion/conclusion in the report is qualified, adverse or disclaimed) No Does the report contain an Emphasis of Matter and/or Other Matter paragraph? Yes Details of current auditor or auditors Current auditor Firm Name Pricewaterhouse Coopers Address One International Towers Watermans Quay ASIC Form 388 Ref 131203477 Page 1 of 2 Form 388 - Copy of financial statements and reports THE MENZIES RESEARCH CENTRE LIMITED ACN 067 359 684 Barangaroo Sydney 2001 Australia Certification I certify that the attached documents are a true copy of the original reports required to be lodged under section 319 of the Corporations Act 2001. Yes Signature Select the capacity in which you are lodging the form Secretary I certify that the information in this form is true and complete and that I am lodging these reports as, or on behalf of, the company. -

$Fu the Federal Redistribution 2008 .*

TheFederal Redistribution 2008 $fu .*,,. s$stqf.<uaf TaSmania \ PublicComment Number 6 HonMichael Hodgman QC MP 3 Page(s) HON MICHAEL HODGMAN QC MP Parliament House Her Maj esty's ShadowAttorney-General HOBART TAS TOOO for the Stateof Tasmania ShadowMinister for Justice Phone: (03)6233 2891 and WorkplaceRelations Fax: (03)6233 2779 Liberal Member for Denison michael.hodgman@ parliament.tas.gov.au The FederalDistribution 2008 RedistributionCommittee for Tasmania 2ndFloor AMP Building 86 CollinsStreet HOBART TAS TOOO Attention: Mr David Molnar Dear Sir, As foreshadowedin my letter to you of 28 April, I now wish to formally obiectto the Submissionscontained in Public SuggestionNo.2 and Public SuggestionNo. 16 that the nameof the Electorateof Denisonshould be changedto Inglis Clark. I havehad the honour to representthe Electorate of Denisonfor over 25 yearsin both the FederalParliament and the State Parliamentand I havenot, in that entire time, had onesingle elector ever suggestto me that the nameof the Electorateshould be changedfrom Denisonto Inglis Clark. The plain fact is that the two southernTasmanian Electoratesof Denisonand Franklin havebeen known as a team,a pair and duo for nearly a century; they havealways been spoken of together; and, the great advantageto the Australian Electoral systemof the two Electoratesbeing recognised as a team,a pair and a duo,would be utterly destroyedif oneof them were to suffer an unwarrantedname change. Whilst I recognisethe legaland constitutionalcontributions of Andrew Inglis Clark the plain fact is that his namewas never put forward by his contemporariesto be honouredby havinga FederalElectorate named after him. Other legal and constitutionalcontributors like Barton, Parkes, Griffith and Deakin were honoured by having Federal Electoratesnamed after them - but Inglis Clark was not. -

Condolence Motion

CONDOLENCE MOTION 7 May 2014 [3.38 p.m.] Mr BARNETT (Lyons) - I stand in support of the motion moved by the Premier and support entirely the views expressed by the Leader for the Opposition and the member for Bass, Kim Booth. As a former senator, having worked with Brian Harradine in his role as a senator, it was a great privilege to know him. He was a very humble man. He did not seek publicity. He was honoured with a state funeral, as has been referred to, at St Mary's Cathedral in Hobart on Wednesday, 23 April. I know that many in this House were there, including the Premier and the Leader of the Opposition, together with the former Prime Minister, the Honourable John Howard, and also my former senate colleague, Don Farrell, a current senator for South Australia because Brian Harradine was born in South Australia and had a background with the Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees Association. Both gentlemen had quite a bit in common. They knew each other well and it was great to see Don Farrell again and catch up with him. He served as an independent member of parliament from 1975 to 2005, so for some 30 years, and was father of the Senate. Interestingly, when he concluded in his time as father of the Senate, a former senator, John Watson, took over as father of the Senate. Brian Harradine was a values- driven politician and he was a fighter for Tasmania. The principal celebrant at the service was Archbishop Julian Porteous and he did a terrific job. -

Ceremonial Sitting of the Tribunal for the Swearing in and Welcome of the Honourable Justice Kerr As President

AUSCRIPT AUSTRALASIA PTY LIMITED ABN 72 110 028 825 Level 22, 179 Turbot Street, Brisbane QLD 4000 PO Box 13038 George St Post Shop, Brisbane QLD 4003 T: 1800 AUSCRIPT (1800 287 274) F: 1300 739 037 E: [email protected] W: www.auscript.com.au TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS O/N H-59979 ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS TRIBUNAL CEREMONIAL SITTING OF THE TRIBUNAL FOR THE SWEARING IN AND WELCOME OF THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KERR AS PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KERR, President THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KEANE, Chief Justice of the Federal Court of Australia THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE BUCHANAN, Presidential Member DEPUTY PRESIDENT S.D. HOTOP DEPUTY PRESIDENT R.P. HANDLEY DEPUTY PRESIDENT D.G. JARVIS THE HONOURABLE R.J. GROOM, Deputy President DEPUTY PRESIDENT P.E. HACK SC DEPUTY PRESIDENT J.W. CONSTANCE THE HONOURABLE B.J.M. TAMBERLIN QC, Deputy President DEPUTY PRESIDENT S.E. FROST DEPUTY PRESIDENT R. DEUTSCH PROF R.M. CREYKE, Senior Member MS G. ETTINGER, Senior Member MR P.W. TAYLOR SC, Senior Member MS J.F. TOOHEY, Senior Member MS A.K. BRITTON, Senior Member MR D. LETCHER SC, Senior Member MS J.L REDFERN PSM, Senior Member MS G. LAZANAS, Senior Member DR I.S. ALEXANDER, Member DR T.M. NICOLETTI, Member DR H. HAIKAL-MUKHTAR, Member DR M. COUCH, Member SYDNEY 9.32 AM, WEDNESDAY, 16 MAY 2012 .KERR 16.5.12 P-1 ©Commonwealth of Australia KERR J: Chief Justice, I have the honour to announce that I have received a commission from her Excellency, the Governor General, appointing me as President of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal. -

Us-Australian Dialogue on Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific ------Tuesday 29 January 2019 the National Press Club, Washington Dc

US-AUSTRALIAN DIALOGUE ON COOPERATION IN THE INDO-PACIFIC ------------------------------------------------ TUESDAY 29 JANUARY 2019 THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, WASHINGTON DC SUPPORTING SPONSORS FOUNDING PARTNERS STRATEGIC PARTNERS TABLE OF CONTENTS 02 WELCOME 03 WELCOME MESSAGES 04 PROGRAM 06 KEYNOTE SPEAKER 06 BIOGRAPHIES 19 SPONSORS Welcome to the US-Australian Dialogue on Cooperation in the 0UKV7HJPÄJ, part of the unique G’Day USA program. The dialogue brings together leaders across the government, business and policy sectors from Australia and the United States. The alliance between these countries is one of the strongest partnerships in the world, and has served as an anchor for peace, prosperity and stability for almost seventy years. Our trade and economic connections are now worth over a trillion dollars annually. Today’s program will deliver thought-provoking panel discussions with leading experts. They will explore the links between trade and security, the geoeconomics of regional connectivity, and how our countries can JVVWLYH[L[VHK]HUJLHMYLLHUKVWLU0UKV7HJPÄJ>LHYLMVY[\UH[L [VILQVPULKI`[OL(\Z[YHSPHU4PUPZ[LYMVY-VYLPNU(ќHPYZ:LUH[VY[OL Hon. Marise Payne, and the Australian Ambassador to the United States, the Hon. Joe Hockey. ;OL 0UKV7HJPÄJ PZ X\PJRS` LTLYNPUN HZ H VUL VM [OL ^VYSK»ZTVZ[ strategically important regions. This dialogue will see Australia and the United States come together to discuss our connections within [OL 0UKV7HJPÄJ HUK OV^ ^L JHU I\PSK \WVU V\Y SVUNZ[HUKPUN collaborations in this region. 2 WELCOME MESSAGES WELCOME FROM THE PERTH USASIA CENTRE The Perth USAsia Centre is pleased to partner with G’Day USA, along with our sister Centre, the United States Studies Centre (USSC) to present in Washington,D.C. -

Ministerial Staff Under the Howard Government: Problem, Solution Or Black Hole?

Ministerial Staff Under the Howard Government: Problem, Solution or Black Hole? Author Tiernan, Anne-Maree Published 2005 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Department of Politics and Public Policy DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3587 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367746 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Ministerial Staff under the Howard Government: Problem, Solution or Black Hole? Anne-Maree Tiernan BA (Australian National University) BComm (Hons) (Griffith University) Department of Politics and Public Policy, Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2004 Abstract This thesis traces the development of the ministerial staffing system in Australian Commonwealth government from 1972 to the present. It explores four aspects of its contemporary operations that are potentially problematic. These are: the accountability of ministerial staff, their conduct and behaviour, the adequacy of current arrangements for managing and controlling the staff, and their fit within a Westminster-style political system. In the thirty years since its formal introduction by the Whitlam government, the ministerial staffing system has evolved to become a powerful new political institution within the Australian core executive. Its growing importance is reflected in the significant growth in ministerial staff numbers, in their increasing seniority and status, and in the progressive expansion of their role and influence. There is now broad acceptance that ministerial staff play necessary and legitimate roles, assisting overloaded ministers to cope with the unrelenting demands of their jobs. However, recent controversies involving ministerial staff indicate that concerns persist about their accountability, about their role and conduct, and about their impact on the system of advice and support to ministers and prime ministers. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Hegemony Over the Heavens: The Chinese and American Struggle in Space by John Hodgson Modinger A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY CENTRE FOR MILITARY AND STRATEGIC STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA AUGUST, 2008 © John Hodgson Modinger 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-44361-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-44361-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Introduction to Volume 1 the Senators, the Senate and Australia, 1901–1929 by Harry Evans, Clerk of the Senate 1988–2009

Introduction to volume 1 The Senators, the Senate and Australia, 1901–1929 By Harry Evans, Clerk of the Senate 1988–2009 Biography may or may not be the key to history, but the biographies of those who served in institutions of government can throw great light on the workings of those institutions. These biographies of Australia’s senators are offered not only because they deal with interesting people, but because they inform an assessment of the Senate as an institution. They also provide insights into the history and identity of Australia. This first volume contains the biographies of senators who completed their service in the Senate in the period 1901 to 1929. This cut-off point involves some inconveniences, one being that it excludes senators who served in that period but who completed their service later. One such senator, George Pearce of Western Australia, was prominent and influential in the period covered but continued to be prominent and influential afterwards, and he is conspicuous by his absence from this volume. A cut-off has to be set, however, and the one chosen has considerable countervailing advantages. The period selected includes the formative years of the Senate, with the addition of a period of its operation as a going concern. The historian would readily see it as a rational first era to select. The historian would also see the era selected as falling naturally into three sub-eras, approximately corresponding to the first three decades of the twentieth century. The first of those decades would probably be called by our historian, in search of a neatly summarising title, The Founders’ Senate, 1901–1910. -

11. the Liberal Campaign in the 2013 Federal Election

11. The Liberal Campaign in the 2013 Federal Election Brian Loughnane On Saturday 7 September 2013 the Liberal and National Coalition won a decisive majority, the Labor Party recorded its lowest primary vote in over 100 years and the Greens had their worst Senate vote in three elections. The Coalition’s success was driven by the support of the Australian people for our Plan to build a strong prosperous economy and a safe, secure Australia. It was the result of strong leadership by Tony Abbott, supported by his colleagues, and a clear strategy which was implemented with discipline and professionalism over two terms of parliament. Under Tony Abbott’s leadership, in the past two elections, the Coalition won a net 31 seats from Labor and achieved a 6.2 per cent nationwide two-party- preferred swing. At the 2013 election the Coalition had swings towards it in every state and territory—ranging from 1.1 per cent in the Northern Territory to 9.4 per cent in Tasmania. At the electorate level, the Coalition won a majority of the primary vote in 51 seats.1 In contrast, Labor only won seven seats with a majority of the primary vote. Table 1: Primary vote at 2007 and 2013 federal elections Primary vote 2007 2013 Change Labor 43 .38% 33 .38% -10 .00% Coalition 42 .09% 45 .55% +3 .46% Greens 7 .79% 8 .65% +0 .86% Others 6 .74% 12 .42% +5 .68% Source: Australian Electoral Commission. Laying the foundations for victory In simple terms, the seats which decided this election were those that did not swing to the Coalition in 2010. -

Our Alumni Educators Their Utas Memories and Careers Utas

NEWS DEC 2012 • Issue 42 OUR ALUMNI EDUCATORS Their UTAS memories and careers UTAS ARCHITECTS UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA Building the world CONTENTS Alumni News is the regular magazine for Contents graduates and friends of the University of Tasmania. UTAS alumni include graduates and diplomates of UTAS, TCAE/TSIT, AMC and staff of three years’ service. Alumni News is prepared by the Communications and Media Office for the Advancement Office. edited by sharon Webb Writers Aaron Smith, Amal Cutler, Cherie Cooper, Eliza Wood, Lana Best, Peter 5 12 Cochrane, Rebecca Cuthill, Sharon Webb Photographers Lana Best, Chris Crerar Design Clemenger Tasmania Advertising enquiries Melanie Roome Acting Director, Advancement Phone +61 3 6226 2842 27 Let us know your story at [email protected] Phone +61 3 6324 3052 3 Michael Field 19 Ava Newman Fax +61 3 6324 3402 Incoming Chancellor “Everyone who can possibly UTAS Advancement Office do so should go to university” Locked Bag 1350 4 Damian Bugg Launceston Tasmania 7250 Departing Chancellor T erry Childs “Teaching studies took 5–8 UTAS architects precedence because of Building the world Tasmania’s teacher shortage” NEWS DEC 2012 • ISSUE 42 5 Benjamin Tan, Vietnam 0 2 Professor Geoffrey sharman Legacy in the genetics of 6 Brennan Chan, Singapore the black-tailed wallaby 7 Ben Duckworth, Switzerland and the potoroo 8 Charles Lim, Malaysia 21–23 UTAS in business 9–11 Alumni News Big Read 21 Lucinda Mills James Boyce 22 John Bye, Trish Bennett and Bonnie Reeves 12–14 UTAS in the arts 23 Penelope’s Produce OUR ALUMNI 12 Pat Brassington to the People EDUCATORS Their UTAS Wayne Hudson Jade Fountain memories and careers 13 Benjamin Gilbert UTAS ARCHITECTS 24 Scholarships UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA Building the world 14 Alan Young S pringing into higher education Cover: At the end of WW2 the University Shaun Wilson of Tasmania dispatched newly trained 25–26 6 Degrees teachers to educate the next generation, 15–20 Our alumni educators Helping us all keep in touch after they gained degrees at the Domain campus in Hobart. -

The Traditionalists Are Restless, So Why Don't They Have a Party of Their Own in Australia?

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities January 2016 The traditionalists are restless, so why don't they have a party of their own in Australia? Gregory C. Melleuish University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers Recommended Citation Melleuish, Gregory C., "The traditionalists are restless, so why don't they have a party of their own in Australia?" (2016). Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 2490. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/2490 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The traditionalists are restless, so why don't they have a party of their own in Australia? Abstract In 1985, B.A. Santamaria speculated about the possibility of a new political party in Australia that would be composed of the Nationals, the traditionalist section of the Liberal Party and the "moderate and anti- extremist section of the blue-collar working class". Keywords their, own, australia, have, they, t, don, party, why, traditionalists, so, restless Publication Details Melleuish, G. (2016). The traditionalists are restless, so why don't they have a party of their own in Australia?. The Conversation, 3 August 1-3. This journal article is available at Research Online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/2490 The traditionalists are restless, so why don't they have a party of their ... https://theconversation.com/the-traditionalists-are-restless-so-why-dont.. -

Caution on the East China Sea October 16 2014

Caution on the East China Sea October 16 2014 Bob Carr As Australia’s Foreign Minister I had quoted several times an acute observation by Lee Kuan Yew. It was on the question of the future character of China. He said: “Peace and security in the Asia-Pacific will turn on whether China emerges as a xenophobic, chauvinistic force, bitter and hostile to the West because it tried to slow down or abort its development, or whether it is educated and involved in the ways of the world – more cosmopolitan, more internationalised and outward looking." I ceased to be Foreign Minister after the Gillard Government was defeated on September 7, 2013. I was representing Australia at the G20 in St Petersburg. As the polling booths at home closed I found myself in Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery, laying flowers on a memorial to the dead of the Second World War. I found myself reflecting on those mass graves – half a million people buried here – and how trivial it was to be voted out of government in a peacetime election compared to the mighty drama that was played out in St Petersburg between 1941 and 1944. Like any politician I thought about what I would do out of government. In the spirit of that observation by Lee Kuan Yew, I committed to work on the Australia-China relationship, becoming Director of a newly established think tank, the Australia-China Relations Institute at the University of Technology, Sydney. I thought that this would be a good vantage point from which to observe this vast question being played out.