Advocacy Group Activity in the New Media Environment David Karpf Brown University, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journolist: Isolated Case Or the Tip of the Iceberg? - Csmonitor.Com Page 1 of 2

JournoList: Isolated case or the tip of the iceberg? - CSMonitor.com Page 1 of 2 JournoList: Isolated case or the tip of the iceberg? Some of the liberal reporters in the JournoList online discussion group suggested that political biases should shape news coverage. Is the principle of journalistic impartiality disappearing? A screen shot of 'The Daily Caller' website on Thursday, which has published more of the 'Journolist' entries on the state of journalism today. By Patrik Jonsson, Staff writer posted July 22, 2010 at 9:30 am EDT Atlanta — Reporters fantasizing about ramming conservatives through plate glass windows or gleefully watching Rush Limbaugh perish: Welcome to the wild and wooly new world of journalism courtesy of the JournoList. A conservative website, the Daily Caller, has begun publishing some of the 25,000 entries by 400 left-leaning journalists who were a part of the online community known as JournoList. In these entries, reporters and media types debate the news of the day, often in intemperate and unguarded terms – like now-former Washington Post reporter David Weigel's suggestion that conservative webmeister Matt Drudge "set himself on fire." Another suggested that members of the group label some Barack Obama as critics racists in their reporting. It is possible, perhaps probable, that the fedora-coiffed journalists of old might have entertained similar thoughts about political characters of the day. But JournoList raises the question of how thoroughly the tone and character of the no-holds-barred blogosphere are reshaping the mainstream media. While it is not clear that the JournoList exchanges influenced coverage, they parroted the snarky language of the blogosphere as well as its pandering to political biases – in some cases, suggesting that those biases should be reflected in news coverage. -

Public Interest Law Center

The Center for Career & Professional Development’s Public Interest Law Center Anti-racism, Anti-bias Reading/Watching/Listening Resources 13th, on Netflix Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates Eyes on the Prize, a 6 part documentary on the Civil Rights Movement, streaming on Prime Video How to be an Antiracist, by Ibram X. Kendi Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, by Bryan Stevenson So You Want to Talk About Race, by Ijeoma Oluo The 1619 Project Podcast, a New York Times audio series, hosted by Nikole Hannah-Jones, that examines the long shadow of American slavery The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, by Michelle Alexander The Warmth of Other Suns, by Isabel Wilkerson When they See Us, on Netflix White Fragility: Why it’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism, by Robin DiAngelo RACE: The Power of an Illusion http://www.pbs.org/race/000_General/000_00-Home.htm Slavery by Another Name http://www.pbs.org/tpt/slavery-by-another-name/home/ I Am Not Your Negro https://www.amazon.com/I-Am-Not-Your-Negro/dp/B01MR52U7T “Seeing White” from Scene on Radio http://www.sceneonradio.org/seeing-white/ Kimberle Crenshaw TedTalk – “The Urgency of Intersectionality” https://www.ted.com/talks/kimberle_crenshaw_the_urgency_of_intersectionality?language=en TedTalk: Bryan Stevenson, “We need to talk about injustice” https://www.ted.com/talks/bryan_stevenson_we_need_to_talk_about_an_injustice?language=en TedTalk Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie “The danger of a single story” https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story 1 Ian Haney Lopez interviewed by Bill Moyers – Dog Whistle Politics https://billmoyers.com/episode/ian-haney-lopez-on-the-dog-whistle-politics-of-race/ Michelle Alexander, FRED Talks https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FbfRhQsL_24 Michelle Alexander and Ruby Sales in Conversation https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a04jV0lA02U The Ezra Klein Show with Eddie Glaude, Jr. -

Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election

Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Faris, Robert M., Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUGUST 2017 PARTISANSHIP, Robert Faris Hal Roberts PROPAGANDA, & Bruce Etling Nikki Bourassa DISINFORMATION Ethan Zuckerman Yochai Benkler Online Media & the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is the result of months of effort and has only come to be as a result of the generous input of many people from the Berkman Klein Center and beyond. Jonas Kaiser and Paola Villarreal expanded our thinking around methods and interpretation. Brendan Roach provided excellent research assistance. Rebekah Heacock Jones helped get this research off the ground, and Justin Clark helped bring it home. We are grateful to Gretchen Weber, David Talbot, and Daniel Dennis Jones for their assistance in the production and publication of this study. This paper has also benefited from contributions of many outside the Berkman Klein community. The entire Media Cloud team at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab has been essential to this research. -

The Senate in Transition Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Nuclear Option1

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYL\19-4\NYL402.txt unknown Seq: 1 3-JAN-17 6:55 THE SENATE IN TRANSITION OR HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE NUCLEAR OPTION1 William G. Dauster* The right of United States Senators to debate without limit—and thus to filibuster—has characterized much of the Senate’s history. The Reid Pre- cedent, Majority Leader Harry Reid’s November 21, 2013, change to a sim- ple majority to confirm nominations—sometimes called the “nuclear option”—dramatically altered that right. This article considers the Senate’s right to debate, Senators’ increasing abuse of the filibuster, how Senator Reid executed his change, and possible expansions of the Reid Precedent. INTRODUCTION .............................................. 632 R I. THE NATURE OF THE SENATE ........................ 633 R II. THE FOUNDERS’ SENATE ............................. 637 R III. THE CLOTURE RULE ................................. 639 R IV. FILIBUSTER ABUSE .................................. 641 R V. THE REID PRECEDENT ............................... 645 R VI. CHANGING PROCEDURE THROUGH PRECEDENT ......... 649 R VII. THE CONSTITUTIONAL OPTION ........................ 656 R VIII. POSSIBLE REACTIONS TO THE REID PRECEDENT ........ 658 R A. Republican Reaction ............................ 659 R B. Legislation ...................................... 661 R C. Supreme Court Nominations ..................... 670 R D. Discharging Committees of Nominations ......... 672 R E. Overruling Home-State Senators ................. 674 R F. Overruling the Minority Leader .................. 677 R G. Time To Debate ................................ 680 R CONCLUSION................................................ 680 R * Former Deputy Chief of Staff for Policy for U.S. Senate Democratic Leader Harry Reid. The author has worked on U.S. Senate and White House staffs since 1986, including as Staff Director or Deputy Staff Director for the Committees on the Budget, Labor and Human Resources, and Finance. -

The Sunrise Movement's Hybrid Organizing

The Sunrise Movement’s Hybrid Organizing: The elements of a massive decentralized and sustained social movement Sarah Lasoff Urban and Environmental Policy Department Occidental College May 11th, 2020 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Matsuoka and the Urban and Environmental Policy department for giving me a place to study this movement. I would like to thank Professor Peter Dreier, Professor Marisol León, Professor Philip Ayoub for teaching me about organizing and social movements. I would like to thank Melissa Mateo and Kayla Williams for sharing your wisdom, your leadership, and passion for change with me. I would like to thank Sunrise organizers, Sara Blazevic, William Lawrence, Danielle Reynolds, Monica Guzman, and Ina Morton for sharing their wisdom and stories with me. I would like to thank the entire Sunrise Movement for already bringing so much change, but more importantly, for it’s current fight for a better future. And finally, I would like to thank my mom, Karen, for being the first person to tell me I can make a difference and my sister, Sophie, for being the person to show me how. 1 Abstract My senior comprehensive project focuses on the Sunrise Movement’s organizing strategies in order to determine how to build massive decentralized social movements. My research question asks, “How does the Sunrise Movement incorporate both structure-based and mass protest strategies in their organizing to build a massive decentralized social movement?” What I found: Sunrise is, theoretically, a mass protest movement that integrates elements of structure based organizing, a hybrid of the two. Sunrise builds a base of active popular support or “people power” and electoral power through the cycles of momentum, moral protest, distributed organizing, local organizing, training, and national organizing with the hopes of using that power in order to engage in mass noncooperation and manifest a new political alignment or “people’s alignment” in the United States. -

MARTIN HÄGGLUND Website

MARTIN HÄGGLUND Website: www.martinhagglund.se APPOINTMENTS Birgit Baldwin Professor of Comparative Literature and Humanities, 2021- Chair of Comparative Literature, Yale University, 2015- Professor of Comparative Literature and Humanities, Yale University, 2014- Tenured Associate Professor of Comparative Literature and Humanities, Yale University, 2012-2014 Junior Fellow, Society of Fellows, Harvard University, 2009-2012 DEGREES Ph.D. Comparative Literature, Cornell University, 2011 M.A. Comparative Literature, emphasis in Critical Theory, SUNY Buffalo, 2005 B.A. General and Comparative Literature, Stockholm University, Sweden, 2001 PUBLICATIONS Books This Life: Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom, Penguin Random House: Pantheon 2019: 465 pages. UK and Australia edition published by Profile Books. *Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Chinese, Korean, Macedonian, Swedish, Thai, and Turkish translations. *Winner of the René Wellek Prize. *Named a Best Book of the Year by The Guardian, The Millions, NRC, and The Sydney Morning Herald. Reviews: The New Yorker, The Guardian, The New Republic, New York Magazine, The Boston Globe, New Statesman, Times Higher Education (book of the week), Jacobin (two reviews), Booklist (starred review), Los Angeles Review of Books, Evening Standard, Boston Review, Psychology Today, Marx & Philosophy Review of Books, Dissent, USA Today, The Believer, The Arts Desk, Sydney Review of Books, The Humanist, The Nation, New Rambler Review, The Point, Church Life Journal, Kirkus Reviews, Public Books, Opulens Magasin, Humanisten, Wall Street Journal, Counterpunch, Spirituality & Health, Dagens Nyheter, Expressen, Arbetaren, De Groene Amsterdammer, Brink, Sophia, Areo Magazine, Spiked, Die Welt, Review 31, Parrhesia: A Journal of Critical Philosophy, Reason and Meaning, The Philosopher, boundary 2, Critical Inquiry, Radical Philosophy. Journal issues on the book: Los Angeles Review of Books (symposium with 6 essays on the book and a 3-part response by the author). -

Conservative Review

Conservative Review Issue #185 Kukis Digests and Opines on this Week’s News and Views July 3, 2011 In this Issue: Additional Rush Links This Week’s Events Say What? Perma-Links Joe Biden Prophecy Watch Must-Watch Media Too much happened this week! Enjoy... A Little Comedy Relief Short Takes The cartoons come from: By the Numbers www.townhall.com/funnies. Polling by the Numbers If you receive this and you hate it and you don’t A Little Bias want to ever read it no matter what...that is fine; Obama-Speak email me back and you will be deleted from my Questions for Obama list (which is almost at the maximum anyway). Political Chess More Proof Obama is an Amateur Previous issues are listed and can be accessed News Before it Happens here: Missing Headlines http://kukis.org/page20.html (their contents are The Greedy Rich described and each issue is linked to) or here: Pinch Happened By Jed Babbin http://kukis.org/blog/ (this is the online directory Where the Tax Money Is they are in) Obama targets the middle class while pretending to tax only the rich. From the WSJ I attempt to post a new issue each Sunday by 5 or Is Democracy Viable? By Thomas Sowell 6 pm central standard time (I sometimes fail at July 4th By Thomas Sowell this attempt). I try to include factual material only, along with Links my opinions (it should be clear which is which). I Additional Sources make an attempt to include as much of this week’s news as I possibly can. -

Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate Hannah Hopper East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2018 Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate Hannah Hopper East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the American Politics Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Political Theory Commons, Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Hopper, Hannah, "Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3402. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3402 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Media and Communication East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Brand and Media Strategy _____________________ by Hannah Hopper May 2018 _____________________ Dr. Susan E. Waters, Chair Dr. Melanie Richards Dr. Phyllis Thompson Keywords: Political Journalist, Twitter, Agenda Setting, Framing, Gatekeeping, Feminist Political Theory, Political Polarization, Presidential Debate, Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump ABSTRACT Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate by Hannah Hopper Past research shows that journalists are gatekeepers to information the public seeks. -

“Creating an Economic System That Works for All”

“CREATING AN ECONOMIC SYSTEM THAT WORKS FOR ALL” Comprehensive Public Policy Initiatives 1 10.07.20 THERE IS NO GOING BACK “Creating an Economic System that Works for All” Public Policy Initiatives There is no going back! The COVID-19 crisis together with the outrage about the ongoing racism in America has revealed what many of us have always known: our current system of capitalism does not work for most Americans. As Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Steven Pearlstein recently wrote, “our economic system has run off the moral rails, offending our sense of fairness, eroding our sense of community, poisoning our politics and rewarding values that easily degenerate into greed and indifference.” This dysfunction was recognized in a recent May 2020 JUST Capital/Harris Poll where 75% of Americans believe our current form of capitalism doesn’t ensure the greater good of society, and only 29% believe it produces the kind of society they want for the next generation or believes it works for the average American.1 In December 2019 the American Sustainable Business Council (ASBC) launched its work on Creating an Economic System that Works for All at its Washington DC Summit and in March 2020 ASBC launched its multi- stakeholder Working Group (details on the participants of the Working Group can be found in the appendix.) The working group has identified the most important business-related public policy initiatives required to Create an Economy that Works for All. ASBC initiated these conversations because while capitalism remains a dynamic force, challenges such as income inequality, crumbling infrastructure, market consolidation, climate change, underinvestment, and the financialization of America’s economy pose serious threats to our continued global leadership and social stability. -

Jan. 20-Jan. 25

This Week in Wall Street Reform | Jan. 20-Jan. 25 Please share this weekly compilation with friends and colleagues. To subscribe, email [email protected], with “This Week” in the subject line. TABLE OF CONTENTS - Consumer Finance and the CFPB - Enforcement - Private Funds - Mortgages and Housing - Small-Business Lending - Student Loans and For-Profit Schools - Systemic Risk - Taxes - Other Topics CONSUMER FINANCE AND THE CFPB U.S. consumer watchdog curtails its power to pursue 'abusive' behavior | Reuters The New York Times also published this story. The U.S. consumer financial watchdog on Friday outlined how it would define “abusive” practices when overseeing companies, in another win for the industry, which has long complained that the agency has overstepped its remit by applying the term far too aggressively. Following the 2007-2009 global financial crisis, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act giving the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) broad authority to stamp out “abusive” acts or practices related to consumer financial products, in addition to “unfair” and “deceptive” practices. While the latter two legal terms were well defined, Dodd-Frank was the first federal law to prohibit “abusive” lending practices CFPB Limits Its Own Powers Against Abusive Conduct in New Policy | Bloomberg The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is putting limits on the ways that it will use its power to pursue banks and other financial companies for abusive practices against consumers. 1 The 2010 Dodd-Frank Act gave the CFPB the unique authority to go after companies for abusive practices alongside long-established standards for pursuing unfair or deceptive acts and practices (UDAP). -

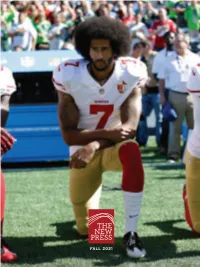

FALL 2021 FALL 2021 Distribution and Sales

THE NEW PRESS U.S. POSTAGE PAID 120 WALL STREET, FL 31 NONPROFIT ORG. NEW YORK, NY 10005-4007 PERMIT NO. 4041 NEW YORK, NY FALL 2021 FALL 2021 Distribution and Sales United States: Australia Ordering Information: Middle East: The New Press is distributed to the NewSouth Books Orders and IPR Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS trade by Two Rivers Distribution, Distribution Middle East Sales Group GARA LaMARCHE (CHAIR) JEFF DEUTSCH an Ingram brand. Alliance Distribution Services, IPR Director, Seminary Co-op Bookstores 9 Pioneer Avenue, PO Box 25731 President, Democracy Alliance Orders and Customer Service: Tuggerah, NSW 2259 Australia 1311 Nicosia THEODORE M. SHAW (VICE-CHAIR) BRUCE GOTTLIEB Ingram Content Group LLC One Ingram +61 (2) 4390 1300 tel CYPRUS Julius L. Chambers Distinguished Attorney Blvd. [email protected] + 357 22872355 tel Professor of Law and Director, BRAD HEBEL La Vergne, TN 37086 (866) 400-5351 tel [email protected] the Center for Civil Rights, Associate Press Director and [email protected] Canada Ordering Information: the University of North Carolina School Director of Operations and Sales, Canadian Manda Group This catalog describes books to be of Law at Chapel Hill Columbia University Press For General International Enquiries: 664 Annette Street, Toronto, ON M6S 2C8 published from September 2021 Ingram Publisher Services International +1 (416) 516-0911 tel through February 2022 SARAH BURNES (SECRETARY) AZIZ HUQ 1400 Broadway, Suite 520 [email protected] Literary Agent, Professor of Law, New York, NY 10018 The New Press The Gernert Company University of Chicago Law School [email protected] South Africa: 120 Wall Street, Fl 31 AMY GLICKMAN (TREASURER) Karis Moelker New York, NY 10005-4007 VIVIEN LABATON Media Lawyer; Former Deputy General Co-Founder, Make It Work International Orders: Sales & Support Representative (212) 629-8802 tel Counsel, Time Inc. -

Save 15%* on AT&T Monthly Wireless Services

PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. Save 15%* on AT&T monthly wireless services. Go union and start saving today! In addition to saving money, you’ll be supporting union workers and their families. AT&T is the only national unionized wireless carrier—with over 40,000 union represented employees. Start Saving Today! Q Visit your local AT&T store Just bring this ad and union identification to your local AT&T store. To find a location near you, visit UnionPlus.org/ATT. (Not available at authorized AT&T dealers or kiosks.) Q Online @ UnionPlus.org/ATT Purchase services and find specials on phones. This offer is available only to qualified union members and retired union members. Union identification is required. The IATSE FAN# is 3508840 The Union Plus FAN# is * Credit approval and new two-year service agreement required. Additional lines for family plans, unlimited plans and Unity Plans or plans combining land line and wireless are not eligible. Other conditions and restrictions apply. ATT-IATSE-0610 INTERNATIONAL ALLIANCE OF THEATRICAL STAGE EMPLOYEES, MOVING PICTURE TECHNICIANS, ARTISTS AND ALLIED CRAFTS OF THE UNITED STATES, ITS TERRITORIES AND CANADA, AFL-CIO, CLC EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Matthew D. Loeb James B. Wood International President General Secretary–Treasurer Thomas C. Short Michael W. Proscia International General Secretary– President Emeritus Treasurer Emeritus Edward C. Powell SECOND QUARTER, 2010 NUMBER 628 International Vice President Emeritus Timothy F. Magee Brian J. Lawlor 1st Vice President 7th Vice President 20017 Van Dyke 1430 Broadway, 20th Floor Detroit, MI 48234 New York, NY 10018 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Michael Barnes Michael F.