Florence Haseltine, Phd, MD Interview Sessions 1 – 2: 9-10 April

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senator Dole FR: Kerry RE: Rob Portman Event

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu TO: Senator Dole FR: Kerry RE: Rob Portman Event *Event is a $1,000 a ticket luncheon. They are expecting an audience of about 15-20 paying guests, and 10 others--campaign staff, local VIP's, etc. *They have asked for you to speak for a few minutes on current issues like the budget, the deficit, and health care, and to take questions for a few minutes. Page 1 of 79 03 / 30 / 93 22:04 '5'561This document 2566 is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas 141002 http://dolearchives.ku.edu Rob Portman Rob Portman, 37, was born and raised in Cincinnati, in Ohio's Second Congressional District, where he lives with his wife, Jane. and their two sons, Jed, 3, and Will~ 1. He practices business law and is a partner with the Cincinnati law firm of Graydon, Head & Ritchey. Rob's second district mots run deep. His parents are Rob Portman Cincinnati area natives, and still reside and operate / ..·' I! J IT ~ • I : j their family business in the Second District. The family business his father started 32 years ago with four others is Portman Equipment Company headquartered in Blue Ash. Rob worked there growing up and continues to be very involved with the company. His mother was born and raised in Wa1Ten County, which 1s now part of the Second District. Portman first became interested in public service when he worked as a college student on the 1976 campaign of Cincinnati Congressman Bill Gradison, and later served as an intern on Crradison's staff. -

California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California 91125

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Caltech Authors - Main DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY PASADENA, CALIFORNIA 91125 PATENTING HUMAN GENES THE ADVENT OF ETHICS IN THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF PATENT LAW Ari Berkowitz University of Oklahoma Daniel J. Kevles California Institute of Technology HUMANITIES WORKING PAPER 165 January 1998 Patenting Human Genes The Advent of Ethics in the Political Economy of Patent Law Ari Berkowitz Daniel J. Kevles Just as the development of technology is a branch of the history of political and economy, so is the evolution of patent law. The claim is well illustrated by the attempts mounted in recent years in the United States and Europe to patent DNA sequences that comprise fragments of human genes. Examination of these efforts reveals a story that is partly familiar: Individuals, companies, and governments have been fighting over the rights to develop potentially lucrative products based on human genes. The battle has turned in large part on whether the grant of such rights would serve a public economic and biotechnological interest. Yet the contest has raised issues that have been, for the most part, historically unfamiliar in patent policy -- whether intellectual property rights should be granted in substances that comprise the fundamental code of human life. The elevation of human DNA to nearly sacred status has fostered the view among many groups that private ownership and exploitation of human DNA sequences is somehow both wrong and threatening, an unwarranted and dangerous violation of a moral code. Attempts to patent human DNA rest legally on Diamond v. -

![Bernadine Healy (1944–2011) [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7768/bernadine-healy-1944-2011-1-1147768.webp)

Bernadine Healy (1944–2011) [1]

Published on The Embryo Project Encyclopedia (https://embryo.asu.edu) Bernadine Healy (1944–2011) [1] By: Darby, Alexis During the twentieth century in the United States, Bernadine Patricia Healy was a cardiologist who served as the first female director of the National Institutes of Health [2] or NIH and the president of both the American Heart Association and the American Red Cross. Healy conducted research on the different manifestations of heart attacks in women compared to men. At the time, many physicians underdiagnosed and mistreated coronary heart disease in women. Healy's research illustrated how coronary heart disease affected women. Healy was also the deputy science advisor to the United States president Ronald Reagan, and during her time at the NIH, she founded the Women's Health Initiative. That initiative was a $625 million research study that aimed to determine how hormones [3] affected diseases specific to postmenopausal women. Through her research and leadership positions, Healy helped improve women's healthcare in the US and helped expand the resources available for research into women's health. Healy was born on 4 August 1944 to Violet McGrath and Michael Healy in New York City, New York. Neither of her parents had completed high school, and they raised their four daughters while running a small perfume shop. Healy attended a school run by the local church for her elementary education. According to long-time friend and coworker, Donna Shalala, Healy realized she wanted to be a doctor at the age of twelve. Shalala said that the priest was worried Healy would become over-educated and forsake what he thought to be the role of a woman as a mother. -

NINR History Book

NINR NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF NURSING RESEARCH PHILIP L. CANTELON, PhD NINR: Bringing Science To Life National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) with Philip L. Cantelon National Institute of Nursing Research National Institutes of Health Publication date: September 2010 NIH Publication No. 10-7502 Library of Congress Control Number 2010929886 ISBN 978-0-9728874-8-9 Printed and bound in the United States of America TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface The National Institute of Nursing Research at NIH: Celebrating Twenty-five Years of Nursing Science .........................................v Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................ix Chapter One Origins of the National Institute of Nursing Research .................................1 Chapter Two Launching Nursing Science at NIH ..............................................................39 Chapter Three From Center to Institute: Nursing Research Comes of Age .....................65 Chapter Four From Nursing Research to Nursing Science ............................................. 113 Chapter Five Speaking the Language of Science ............................................................... 163 Epilogue The Transformation of Nursing Science ..................................................... 209 Appendices A. Oral History Interviews .......................................................................... 237 B. Photo Credits ........................................................................................... 239 -

Congressional Record—Senate S6769

December 7, 2016 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S6769 don’t ask, don’t tell. He signed Execu- streak of private sector job growth from the House came over in the midst tive orders protecting LGBT workers. ever. We have the lowest unemploy- of all their work. I love them. I have Americans are now free to marry the ment rate in nearly a decade. enjoyed working with them. person they love, regardless of their After 8 years of President Obama, we I look around this Chamber, and I re- gender. are now as a country on a sustainable alize the reason I am able to actually As Commander in Chief, President path to fight climate change and grow leave is because I know each of you and Obama brought bin Laden to justice. renewable energy sources. We are more your passion to make life better for These are just a few aspects of Presi- respected around the world. We reached people, and that is what it is all about. dent Obama’s storied legacy, and it is international agreements to curb cli- When I decided not to run for reelec- still growing—what a record. It is a mate change, stop Iran from obtaining tion, you know how the press always legacy of which he should be satisfied. a nuclear weapon, and we are on the follows you around. They said: ‘‘Is this America is better because of this good path to normalizing relations with our bittersweet for you?’’ man being 8 years in the White House. neighbor Cuba. My answer was forthcoming: ‘‘No I am even more impressed by who he Our country has made significant way is it bitter. -

Barbara A. Mikulski

Barbara A. Mikulski U.S. SENATOR FROM MARYLAND TRIBUTES IN THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES E PL UR UM IB N U U S VerDate Aug 31 2005 12:18 May 15, 2017 Jkt 098900 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\BYEBYE\BYEBYE16\23051.TXT KAYNE congress.#15 Barbara A. Mikulski VerDate Aug 31 2005 12:18 May 15, 2017 Jkt 098900 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\BYEBYE\BYEBYE16\23051.TXT KAYNE 73-500_mikulski.eps S. DOC. 114–22 Tributes Delivered in Congress Barbara A. Mikulski United States Congressman 1977–1987 United States Senator 1987–2017 ÷ U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2017 VerDate Aug 31 2005 12:18 May 15, 2017 Jkt 098900 PO 00000 Frm 00005 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\BYEBYE\BYEBYE16\23051.TXT KAYNE Compiled under the direction of the Joint Committee on Printing VerDate Aug 31 2005 12:18 May 15, 2017 Jkt 098900 PO 00000 Frm 00006 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\BYEBYE\BYEBYE16\23051.TXT KAYNE CONTENTS Page Biography .................................................................................................. v Farewell Address ...................................................................................... vii Proceedings in the Senate: Tributes by Senators: Boozman, John, of Arkansas ..................................................... 37 Boxer, Barbara, of California .................................................... 18, 20 Cardin, Benjamin L., of Maryland ............................................ 11, 15 Casey, Robert P., Jr., of Pennsylvania ..................................... 11, 36 Cochran, -

A Case Study of Two Florida Engineering Programs Arland Nguema Ndong University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2011 Investigating the Role of the Internet in Women and Minority STEM Participation: A Case Study of Two Florida Engineering Programs Arland Nguema Ndong University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Engineering Commons, Higher Education and Teaching Commons, and the Other Computer Sciences Commons Scholar Commons Citation Nguema Ndong, Arland, "Investigating the Role of the Internet in Women and Minority STEM Participation: A Case Study of Two Florida Engineering Programs" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3734 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Investigating the Role of the Internet in Women and Minority STEM Participation: A Case Study of Two Florida Engineering Programs by Arland Nguema Ndong A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Kathryn M. Borman, Ph.D. Antoinette T. Jackson, Ph.D. Jacqueline H. Messing, Ph.D. Donald Dellow, Ph.D. Maya A. Trotz, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 2, 2011 Keywords: higher education, STEM recruitment and retention, race, gender, Websites Copyright© 2011, Arland Nguema Ndong DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to my wife, Sidonie, and to our three lovely children, Lizzie, Lindsay, and Lucas Elijah. -

Encyclopedia of Women in Medicine.Pdf

Women in Medicine Women in Medicine An Encyclopedia Laura Lynn Windsor Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England Copyright © 2002 by Laura Lynn Windsor All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Windsor, Laura Women in medicine: An encyclopedia / Laura Windsor p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1–57607-392-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Women in medicine—Encyclopedias. [DNLM: 1. Physicians, Women—Biography. 2. Physicians, Women—Encyclopedias—English. 3. Health Personnel—Biography. 4. Health Personnel—Encyclopedias—English. 5. Medicine—Biography. 6. Medicine—Encyclopedias—English. 7. Women—Biography. 8. Women—Encyclopedias—English. WZ 13 W766e 2002] I. Title. R692 .W545 2002 610' .82 ' 0922—dc21 2002014339 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper I. Manufactured in the United States of America For Mom Contents Foreword, Nancy W. Dickey, M.D., xi Preface and Acknowledgments, xiii Introduction, xvii Women in Medicine Abbott, Maude Elizabeth Seymour, 1 Blanchfield, Florence Aby, 34 Abouchdid, Edma, 3 Bocchi, Dorothea, 35 Acosta Sison, Honoria, 3 Boivin, Marie -

NIHAA Update Said Dr

I I z he Newsletter of the / NIH Alumni Association · Spring 1993 Vol. 5, No. 1 date NIHAA Presents Its First Liotta Recharting Public Service Award to Course for Intramural Chairman Natcher Research at NIH Citing his "active advocacy of bio Since he became NI H's new deputy medical research as a necessary nation director for intramural research in Jul y al i11 vestmen t"· the NIH Alumni Asso 1992, Dr. Lance Liotta has left his ciation (NIH AA) has selected Rep. imprint on virtually every facet of NlH William H. Natcher (D-Ky.). chairman campus research life- from paychecks of the House Appropriations to parking, and protocol review to poli Committee, to receive its first NLHAA cies on consulring. Public Service A ward. The award was "I've had a very good experience established in 1992 by the NJHAA here," notes Liona. ·'J want everyone to board of directors to recogni ze individ have that same experience." Liotta is a uals who have rendered outstanding 17-year veteran of NTI-£'s lntramurai service through strengthening public Research Progran1 (IRP). He has spent understandi.ng and support of biomed NIH director Dr. Bernadine Healy announces most of his scientific Hfe investigating ical research. her resignation at a press conference at how cancer cells metastasize and invade Chairman Na tc her, now in his 40th Stone House on Feb . 26. new tissue-the main cause of death in year as a member of Congress, has cancer patients. Liocta wants every NTH been a friend and champion of Nll-1 'Deeply Honored To Have Served' scientist to have what he enjoys him during his long tenure as a member of self-a stimulating, rewarding career at the appropriations commi11ee. -

View Entire Issue in Pdf Format

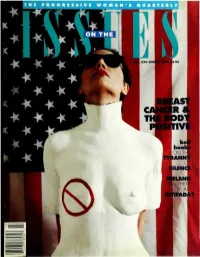

MA ARTERLY HE I 2 853 7 0 7447 o Join the Celebration! March is National Women's History Month. Discover A New World: Women's History "Women's History11- a topic that may be unfamiliar, is a whole "new world" of discovery awaiting you - a long neglected part of our heritage as women and as Americans. Discover a New World - populated by inspiring, courageous, dedicated, compassionate women from all walks of life who have shaped their families, communities and the intellectual and artistic climate of their time, but have been ignored by historians because of their sex. a New World - of organizations and events that had a major impact on the social and political institutions of this nation, but have been forgotten because the major players were female. a New World -of possibility for yourself and your children, opened by the community of active and dynamic women who have come before us. The National Women's History Project promotes the rediscovery of women's history in the classroom and community through the development and sale of posters, videos, biographies, overviews, classroom materials and lots of fun items like coloring books, card games, coffee mugs, lapel pins, etc. For a copy of the NWHP's 48-page catalog of multicultural women's history posters, books, videos and other items for all ages, send $1.00 to: National Women's History Project, Catalog Request 7738 Bell Road, Windsor, CA 95492 or call 707-838-6000. CONTENTS Winter 1992 FEATURES 8 Northern Ireland: Oppression, Struggle, and Outright Murder An Interview with Bernadette Devlin McAliskey By Betsy Swart 12 Reel Feminism vs. -

APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981- 1989 – REAGAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS

COUNSEL TO THE PRESIDENT, OFFICE OF THE: APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981- 1989 – REAGAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS Material noted in bold within this collection is currently available for research use. If a folder is available for research use it may still have withdrawn material due to Freedom of Information Act restrictions. Most frequent withdrawn material is national security classified material, personal privacy, protection of the President, etc. Any non-bolded folder is closed for research. The non-bolded folders are subject to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests under the provisions of the Presidential Records Act (PRA). If you are interested in submitting a FOIA request for access to any of the unavailable records or have any questions about these collections or series, please contact our archival staff at 1-800- 410-8354, outside the US at 1-805-577-4012, or email [email protected] COUNSEL TO THE PRESIDENT, OFFICE OF THE: APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981-1989 The Appointee File consists of four series: SERIES I: Appointee Files by Position; SERIES II: Appointee Files by Individual; SERIES III: The President's Private Sector Survey on Cost Control, and SERIES IV: Appointment Memoranda Within Series II, we are using the following organizational abbreviations for all unprocessed folder titles: ACDA - Arms Control & Disarmament FBI - Federal Bureau of Investigation Agency FCC - Federal Communications ACTION Commission AID - Agency for International FDIC - Federal Deposit Insurance Development Corporation CIA - Central Intelligence Agency FEMA - Federal Emergency Management DOAg - Dept. of Agriculture Agency DOC - Dept. of Commerce FNMA - Federal National Mortgage DOD - Dept. of Defense Association DOE - Dept. -

Senate Section (PDF)

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 114 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 162 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 7, 2016 No. 176 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY have fittingly been renamed for Beau called to order by the President pro LEADER Biden in this legislation. I will have tempore (Mr. HATCH). The PRESIDING OFFICER (Mr. more to say about the Vice President PAUL). The majority leader is recog- when he joins us again this afternoon, f nized. but for now I look forward to passing the 21st Century Cures Act today. f PRAYER On another matter, we will have an- LEGISLATION BEFORE THE other important vote this afternoon. It The PRESIDENT pro tempore. To- SENATE is a vote to move forward on the na- day’s opening prayer will be offered by Mr. MCCONNELL. Mr. President, the tional defense authorization conference Elder D. Todd Christofferson, a mem- continuing resolution was filed in the report. ber of the Quorum of the Twelve Apos- House yesterday. As we wait for the We all know the world the next ad- tles of The Church of Jesus Christ of House to take the next step, I encour- ministration will inherit is a difficult Latter-day Saints in Salt Lake City. age all Members to continue reviewing and dangerous one. There are many The guest Chaplain offered the fol- the legislative text, which has been threats. There are numerous national lowing prayer: available for some time.