The University of Tennessee Knoxville an Interview With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

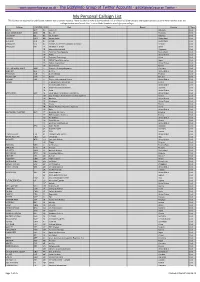

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ORDER TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2E FEDERAL AVIATION Effective Date: ADMINISTRATION July 24, 2014 Air Traffic Organization Policy Subject: Contractions Includes Change 1 dated 11/13/14 https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/CNT/3-3.HTM A 3- Company Country Telephony Ltr AAA AVICON AVIATION CONSULTANTS & AGENTS PAKISTAN AAB ABELAG AVIATION BELGIUM ABG AAC ARMY AIR CORPS UNITED KINGDOM ARMYAIR AAD MANN AIR LTD (T/A AMBASSADOR) UNITED KINGDOM AMBASSADOR AAE EXPRESS AIR, INC. (PHOENIX, AZ) UNITED STATES ARIZONA AAF AIGLE AZUR FRANCE AIGLE AZUR AAG ATLANTIC FLIGHT TRAINING LTD. UNITED KINGDOM ATLANTIC AAH AEKO KULA, INC D/B/A ALOHA AIR CARGO (HONOLULU, UNITED STATES ALOHA HI) AAI AIR AURORA, INC. (SUGAR GROVE, IL) UNITED STATES BOREALIS AAJ ALFA AIRLINES CO., LTD SUDAN ALFA SUDAN AAK ALASKA ISLAND AIR, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ALASKA ISLAND AAL AMERICAN AIRLINES INC. UNITED STATES AMERICAN AAM AIM AIR REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AIM AIR AAN AMSTERDAM AIRLINES B.V. NETHERLANDS AMSTEL AAO ADMINISTRACION AERONAUTICA INTERNACIONAL, S.A. MEXICO AEROINTER DE C.V. AAP ARABASCO AIR SERVICES SAUDI ARABIA ARABASCO AAQ ASIA ATLANTIC AIRLINES CO., LTD THAILAND ASIA ATLANTIC AAR ASIANA AIRLINES REPUBLIC OF KOREA ASIANA AAS ASKARI AVIATION (PVT) LTD PAKISTAN AL-AAS AAT AIR CENTRAL ASIA KYRGYZSTAN AAU AEROPA S.R.L. ITALY AAV ASTRO AIR INTERNATIONAL, INC. PHILIPPINES ASTRO-PHIL AAW AFRICAN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIBYA AFRIQIYAH AAX ADVANCE AVIATION CO., LTD THAILAND ADVANCE AVIATION AAY ALLEGIANT AIR, INC. (FRESNO, CA) UNITED STATES ALLEGIANT AAZ AEOLUS AIR LIMITED GAMBIA AEOLUS ABA AERO-BETA GMBH & CO., STUTTGART GERMANY AEROBETA ABB AFRICAN BUSINESS AND TRANSPORTATIONS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFRICAN BUSINESS THE CONGO ABC ABC WORLD AIRWAYS GUIDE ABD AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC ICELAND ATLANTA ABE ABAN AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ABAN OF) ABF SCANWINGS OY, FINLAND FINLAND SKYWINGS ABG ABAKAN-AVIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION ABAKAN-AVIA ABH HOKURIKU-KOUKUU CO., LTD JAPAN ABI ALBA-AIR AVIACION, S.L. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. U M I films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or p o o r quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UM I directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Com pany 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 1342567 They also flew: Women aviators in Tennessee, 1922-1950 Leonhirth, Janene Gupton, M.A. -

UFTAA Congress Kuala Lumpur 2013

UFTAA Congress Kuala Lumpur 2013 Duncan Bureau Senior Vice President Global Sales & Distribution The Airline industry is tough "If I was at Kitty Hawk in 1903 when Orville Wright took off, and would have been farsighted enough, and public-spirited enough -- I owed it to future capitalists -- to shoot them down…” Warren Buffet US Airline Graveyard – A Only AAXICO Airlines (1946 - 1965, to Saturn Airways) Air General Access Air (1998 - 2001) Air Great Lakes ADI Domestic Airlines Air Hawaii (1960s) Aeroamerica (1974 – 1982) Air Hawaii (ceased Operations in 1986) Aero Coach (1983 – 1991) Air Hyannix Aero International Airlines Air Idaho Aeromech Airlines (1951 - 1983, to Wright Airlines) Air Illinois AeroSun International Air Iowa AFS Airlines Airlift International (1946 - 81) Air America (operated by the CIA in SouthEast Asia) Air Kentucky Air America (1980s) Air LA Air Astro Air-Lift Commuter Air Atlanta (1981 - 88) Air Lincoln Air Atlantic Airlines Air Link Airlines Air Bama Air Link Airways Air Berlin, Inc. (1978 – 1990) Air Metro Airborne Express (1946 - 2003, to DHL) Air Miami Air California, later AirCal (1967 - 87, to American) Air Michigan Air Carolina Air Mid-America Air Central (Michigan) Air Midwest Air Central (Oklahoma) Air Missouri Air Chaparral (1980 - 82) Air Molakai (1980) Air Chico Air Molakai (1990) Air Colorado Air Molakai-Tropic Airlines Air Cortez Air Nebraska Air Florida (1972 - 84) Air Nevada Air Gemini Air New England (1975 - 81) US Airline Graveyard – Still A Air New Orleans (1981 – 1988) AirVantage Airways Air -

Denied Boarding Files 1978

National Archives and Records Administration 8601 Adelphi Road Co/Jege Parle, Maryland 20740-6001 Accession Number: NN3-197-89-1 Introduction Ageney Background Information The Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) was established within the Department ofCommerce ueder Reorganization Plans 3 and 4 of 1940, effective June 30, 1940. The Board was made an independent agency by the Federal Aviation Act of 1958 (72 Stat. 731), effective January I, 1959. The CAB was given responsibility for regulating economic aspects ofair carrier operations, promulgating aafety standards, investigating accidents, and promoting international air transportation. The CAB authori2ed domestic air carriers to engage in interstate and foreign transportation and regulates the operations offoreign air carriers in the United States. It had jurisdiction over subsidies paid air earners and over tariffs, rates, and fares charged for air transportation and for carrying the mail. The CAB, which regulated the accounting procedures ofair carriers and their financial and business relationships, required the carders to file regular financial aod operating reports aod made that dsta availshle to other Government agencies and the public. The Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) cessed to exist (sunsetted)onDecernber 31, 1984. Beginning on Janwuy I, 1985, air carrier reports were bandied by the Depa~tment of Tmnsportation (D01), Research aod Special Programs Administration (RSPA), Office of Aviatlon Information Management. National Archives (NA) Background Information At one time the National Archives operated a depository for non-archival macbine-readsble records ofhigh current interest, which have been ntede, received, or acquired by Federal agencies. Under the tenns ofinter-agency agreements of Septerober 9, 1977, Janwuy 2, 1979, November 14, 1979, and March 25, 1982, CAB traosferred copies of many ofits machine-readsble dsta files to the physical custody ofthe National Archives. -

Model Builder November 1980

7 volume 10, number 106 OVEMBER 1980 IGD 08545 • FOKKER s Classic G ass fö • R. C SCALE WORLD CHAMPS 74820 08545 NOVEMBER 1980 volume 10, number 106 621 West Nineteenth St., Costa Mesa, California 92627 Phone: (714) 645-8830 STAFF CONTENTS PUBLISHER Walter L. Schroder EDITOR FEATURES Wm. C. Northrop, )r. W O R K B E N C H , Bill Northrop....................................................................... 6 GENERAL MANAGER O V E R T H E C O U N T E R , Phil Bernhardt ............................................... 7 Walter L. Schroder ASSISTANT EDITOR H O W T O FLY P A T T E R N , Dick Hanson............................................... 9 Phil Bernhardt T H E F L IG H T IN S T R U C T O R , Dave Brown...................................... 10 ASSISTANT GENERAL MANAGER "1 T O 1” R / C S C A L E , Bob Underwood............................................... 11 Anita Northrop ART DEPARTMENT G IAN T SCALE FLIGHT LINE, Lee Taylor ........................................ 22 Al Patterson F U E L L IN E S , |oe Klause.................................................................................... 25 P Y L O N , Jim Gager.................................................................................................. 26 OFFICE STAFF Mary Ann Bell HALF-A "SPO RT” SCENE, Larry Renger.......................................... 28 Edie Downs P L U G S P A R K S , John Pond ........................................................................... 32 Debbee Holobaugh Pat Patton S O A R IN G D O L D R U M S , Dave Thornburg...................................... 38 A. Valcarsel R / C S O A R IN G , Dr. Larry Fogel................................................................... 39 CONTRIBUTING EDITORS " M IS S C IR C U S C IR C U S ” R E V IE W , Jerry Dunlap ................. -

Air Transport Pilot Supply and Demand Current State and Effects of Recent Legislation

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and EDUCATION AND THE ARTS decisionmaking through research and analysis. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from www.rand.org as a public service INFRASTRUCTURE AND of the RAND Corporation. TRANSPORTATION INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY Support RAND SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Browse Reports & Bookstore TERRORISM AND Make a charitable contribution HOMELAND SECURITY For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the Pardee RAND Graduate School View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the Pardee RAND Graduate School (PRGS) dissertation series. PRGS dissertations are produced by graduate fellows of the Pardee RAND Graduate School, the world’s leading producer of Ph.D.’s in policy -

Page Control Chart

4/8/10 JO 7340.2A CHG 2 ERRATA SHEET SUBJECT: Order JO 7340.2, Contractions This errata sheet transmits, for clarity, revised pages and omitted pages from Change 2, dated 4/8/10, of the subject order. PAGE CONTROL CHART REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED 3−2−31 through 3−2−87 . various 3−2−31 through 3−2−87 . 4/8/10 Attachment Page Control Chart i 48/27/09/8/10 JO 7340.2AJO 7340.2A CHG 2 Telephony Company Country 3Ltr EQUATORIAL AIR SAO TOME AND PRINCIPE SAO TOME AND PRINCIPE EQL ERAH ERA HELICOPTERS, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ERH ERAM AIR ERAM AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC IRY REPUBLIC OF) ERFOTO ERFOTO PORTUGAL ERF ERICA HELIIBERICA, S.A. SPAIN HRA ERITREAN ERITREAN AIRLINES ERITREA ERT ERTIS SEMEYAVIA KAZAKHSTAN SMK ESEN AIR ESEN AIR KYRGYZSTAN ESD ESPACE ESPACE AVIATION SERVICES DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC EPC OF THE CONGO ESPERANZA AERONAUTICA LA ESPERANZA, S.A. DE C.V. MEXICO ESZ ESRA ELISRA AIRLINES SUDAN RSA ESSO ESSO RESOURCES CANADA LTD. CANADA ERC ESTAIL SN BRUSSELS AIRLINES BELGIUM DAT ESTEBOLIVIA AEROESTE SRL BOLIVIA ROE ESTERLINE CMC ELECTRONICS, INC. (MONTREAL, CANADA) CANADA CMC ESTONIAN ESTONIAN AIR ESTONIA ELL ESTRELLAS ESTRELLAS DEL AIRE, S.A. DE C.V. MEXICO ETA ETHIOPIAN ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES CORPORATION ETHIOPIA ETH ETIHAD ETIHAD AIRWAYS UNITED ARAB EMIRATES ETD ETRAM ETRAM AIR WING ANGOLA ETM EURAVIATION EURAVIATION ITALY EVN EURO EURO CONTINENTAL AIE, S.L. SPAIN ECN CONTINENTAL EURO EXEC EUROPEAN EXECUTIVE LTD UNITED KINGDOM ETV EURO SUN EURO SUN GUL HAVACILIK ISLETMELERI SANAYI VE TURKEY ESN TICARET A.S. -

Bourbon County Industrial Reports for Kentucky Counties

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Bourbon County Industrial Reports for Kentucky Counties 1980 Industrial Resources: Bourbon County - Paris Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/bourbon_cty Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Growth and Development Commons, and the Infrastructure Commons Recommended Citation Kentucky Library Research Collections, "Industrial Resources: Bourbon County - Paris" (1980). Bourbon County. Paper 9. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/bourbon_cty/9 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bourbon County by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. w M ^ 4c iM 0 M s C'!^ 0j .it? %.j ^ k' .-£i .jS# ->V « i? ^ s-.sm "i'i ..i?J% 1^*...,J •3^? '? W H'k-- •■'f '\* P4fi/5 DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE PARIS, KENTUCKY —- Industrial Site 180 — 17 Acres For morfi information contact Mr. Rax Taylor, City Hall, 800 Pleasant Street, Paris, Kentucky 40361 or the Kentucky Department of Commerce, Industrial Development Division, Capital Plaza Tower, Frankfort, Kentucky 40801. station ons Water Existing Industries A. Dura Corp. B. Btuegrats industries ? C. Hansley Enterprises, inc. gallons O. International Spike, inc. Water E. Gay Beli Corp. F. Ramset Fasteners G. Mallinckrodt, inc. H. Paris Manufacturing Co., inc. ^ LOCATION: WiUiin southwest city limits ZONING: -

The Structuring of Neoliberalism in the US Airline Industry

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 9-2012 Organizing Markets: The trS ucturing of Neoliberalism in the U.S. Airline Industry Dustin Robert Avent-Holt University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Avent-Holt, Dustin Robert, "Organizing Markets: The trS ucturing of Neoliberalism in the U.S. Airline Industry" (2012). Open Access Dissertations. 611. https://doi.org/10.7275/8z4d-d912 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/611 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Organizing Markets: The Structuring of Neoliberalism in the U.S. Airline Industry A Dissertation Presented by DUSTIN ROBERT AVENT-HOLT Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 2012 Sociology © Copyright by Dustin Avent-Holt 2012 All Rights Reserved Organizing Markets: The Structuring of Neoliberalism in the U.S. Airline Industry A Dissertation Presented by DUSTIN ROBERT AVENT-HOLT Approved as to Style and Content by: _________________________________ Donald Tomaskovic-Devey, Chair ________________________________ Joya Misra, Member ________________________________ Robert Faulkner, Member ________________________________ Michelle Budig, Member ________________________________ Michael Ash, Member ______________________________ Donald Tomaskovic-Devey, Chair Department of Sociology ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS What seems like to many years ago I started an unpredictable journey into academia because I wanted to understand the world around me and in some way transform that world. -

Bell County Industrial Reports for Kentucky Counties

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Bell County Industrial Reports for Kentucky Counties 1986 Industrial Resources: Bell County - Middlesboro & Pineville Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/bell_cty Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Growth and Development Commons, and the Infrastructure Commons Recommended Citation Kentucky Library Research Collections, "Industrial Resources: Bell County - Middlesboro & Pineville" (1986). Bell County. Paper 11. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/bell_cty/11 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bell County by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. T7 V .cont^ RESOURCES FOR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT k',& I as. ^ ■ SifWPl , i> af ill Si; ■ J-j'- Mill''!;-: 1 ilSi^flif:':: !«?••.iiit. rivAj^ !_'■ o i <\ <*i vL 2^@H~ •♦Of 4. & tks fl' m.'iB jt**-i-^i • > <V I I '«>! !»<••••• «• *<^'1 • '" » /f— " 'f KENTUCKY 11k busmess environmem is nglbl; i!Ca«^V?S5fr 'i " ' i i .' "'< ^ -T » i iHv ' r.ft''^^s«sW^w -w -S-. RESOURCES FOR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT MIDDLESBORO AND PINEVILLE, KENTUCKY Prepared by The Kentucky Department of Economic Development Division of Research and Planning in cooperation with The Middlesboro Chamber of Commerce and The City of Pineville 1986 Program manager - Andrew Dennis; research - James R. Thompson; clerical - Bobbi -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type GINTA GNT 0A Amber Air Lithuania Civil BLUE MESSENGER BMS 0B Blue Air Romania Civil CATOVAIR IBL 0C IBL Aviation Mauritius Civil DARWIN DWT 0D Darwin Airline Switzerland Civil JETCLUB JCS 0J Jetclub Switzerland Civil VASCO AIR VFC 0V Vietnam Air Services Company (VASCO) Vietnam Civil AMADEUS AGT 1A Amadeus IT Group Spain Civil 1B Abacus International Singapore Civil 1C Electronic Data Systems Switzerland Civil 1D Radixx United States Civil 1E Travelsky Technology China Civil 1F INFINI Travel Information Japan Civil 1G Galileo International United States Civil 1H Siren-Travel Russia Civil CIVIL AIR AMBULANCE AMB 1I Deutsche Rettungsflugwacht Germany Civil EXECJET EJA 1I NetJets United States Civil FRACTION NJE 1I NetJets Europe Portugal Civil NAVIGATOR NVR 1I Novair Sweden Civil PHAZER PZR 1I Sky Trek International Airlines United States Civil Sunturk 1I Pegasus Hava Tasimaciligi Turkey Civil 1I Sierra Nevada Airlines United States Civil 1K Southern Cross Distribution Australia Civil 1K Sutra United States Civil OPEN SKIES OSY 1L Open Skies Consultative Commission United States Civil