Language and Identity: Chinese Nation-Building, Localization And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

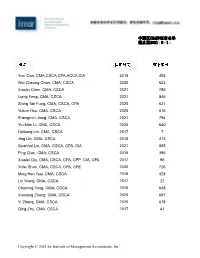

中国区cma持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日

中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日 Yixu Cao, CMA,CSCA,CPA,ACCA,CIA 2019 492 Wai Cheung Chan, CMA, CSCA 2020 622 Xiaolin Chen, CMA, CSCA 2021 785 Liang Feng, CMA, CSCA 2021 845 Shing Tak Fung, CMA, CSCA, CPA 2020 621 Yukun Hsu, CMA, CSCA 2020 676 Shengmin Jiang, CMA, CSCA 2021 794 Yiu Man Li, CMA, CSCA 2020 640 Huikang Lin, CMA, CSCA 2017 7 Jing Lin, CMA, CSCA 2018 415 Quanhui Liu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CIA 2021 855 Ping Qian, CMA, CSCA 2018 396 Xiaolei Qiu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFP, CIA, CFA 2017 96 Yufei Shan, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFE 2020 726 Ming Han Tsai, CMA, CSCA 2018 428 Lin Wang, CMA, CSCA 2017 22 Chunling Yang, CMA, CSCA 2020 648 Xiaolong Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 697 Yi Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 678 Qing Zhu, CMA, CSCA 2017 41 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. 中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日 Siha A, CMA 2020 81134 Bei Ai, CMA 2020 84918 Danlu Ai, CMA 2021 94445 Fengting Ai, CMA 2019 75078 Huaqin Ai, CMA 2019 67498 Jie Ai, CMA 2021 94013 Jinmei Ai, CMA 2020 79690 Qingqing Ai, CMA 2019 67514 Weiran Ai, CMA 2021 99010 Xia Ai, CMA 2021 97218 Xiaowei Ai, CMA, CIA 2019 75739 Yizhan Ai, CMA 2021 92785 Zi Ai, CMA 2021 93990 Guanfei An, CMA 2021 99952 Haifeng An, CMA 2021 92781 Haixia An, CMA 2016 51078 Haiying An, CMA 2021 98016 Jie An, CMA 2012 38197 Jujie An, CMA 2018 58081 Jun An, CMA 2019 70068 Juntong An, CMA 2021 94474 Kewei An, CMA 2021 93137 Lanying An, CMA, CPA 2021 90699 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. -

Characteristics of Chinese Poetic-Musical Creations

Characteristics of Chinese Poetic-Musical Creations Yan GENG1 Abstract: The present study intoduces a series of characteristics related to Chinese poetry. It shows that, together with rhythmical structure and intonation (which has a crucial role in conveying meaning), an additional, fundamental aspect of Chinese poetry lies in the latent, pictorial effect of the writing. Various genres and forms of Chinese poetry are touched upon, as well as a series of figures of speech, themes (nature, love, sadness, mythology etc.) and symbols (particularly of vegetal and animal origin), which are frequently encountered in the poems. Key-words: rhythm, intonation, system of tones, rhyme, system of writing, figures of speech 1. Introduction In his Advanced Music Theory course, &RQVWDQWLQ 5kSă VKRZV WKDW ³we can differentiate between two levels of the phenomenon of rhythm: the first, a general philosophical one, meaning, within the context of music, the ensemble of movements perceived, thus the macrostructural level; the second, the micro-VWUXFWXUH ZKHUH UK\WKP PHDQV GXUDWLRQV « LQWHQVLWLHVDQGWHPSR « 0RUHRYHUZHFDQVD\WKDWUK\WKPGRHVQRWH[LVWEXWUDWKHUMXVW the succession of sounds in time [does].´2 Studies on rhythm, carried out by ethno- musicology researchers, can guide us to its genesis. A first fact that these studies point towards is the indissoluble unity of the birth process of artistic creation: poetry, music (rhythm-melody) and dance, which manifested syncretically for a very lengthy period of time. These aspects are not singular or characteristic for just one culture, as it appears that they have manifested everywhere from the very beginning of mankind. There is proof both in Chinese culture, as well as in ancient Romanian culture, that certifies the existence of a syncretic development of the arts and language. -

Syllabus 1 Lín Táo 林燾 and Gêng Zhènshëng 耿振生

CHINESE 542 Introduction to Chinese Historical Phonology Spring 2005 This course is a basic introduction at the graduate level to methods and materials in Chinese historical phonology. Reading ability in Chinese is required. It is assumed that students have taken Chinese 342, 442, or the equivalent, and are familiar with articulatory phonetics concepts and terminology, including the International Phonetic Alphabet, and with general notions of historical sound change. Topics covered include the periodization of the Chinese language; the source materials for reconstructing earlier stages of the language; traditional Chinese phonological categories and terminology; fânqiè spellings; major reconstruction systems; the use of reference materials to determine reconstructions in these systems. The focus of the course is on Middle Chinese. Class: Mondays & Fridays 3:30 - 5:20, Savery 335 Web: http://courses.washington.edu/chin532/ Instructor: Zev Handel 245 Gowen, 543-4863 [email protected] Office hours: MF 2-3pm Grading: homework exercises 30% quiz 5% comprehensive test 25% short translations 15% annotated translation 25% Readings: Readings are available on e-reserves or in the East Asian library. Items below marked with a call number are on reserve in the East Asian Library or (if the call number starts with REF) on the reference shelves. Items marked eres are on course e-reserves. Baxter, William H. 1992. A handbook of Old Chinese phonology. (Trends in linguistics: studies and monographs, 64.) Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. PL1201.B38 1992 [eres: chapters 2, 8, 9] Baxter, William H. and Laurent Sagart. 1998 . “Word formation in Old Chinese” . In New approaches to Chinese word formation: morphology, phonology and the lexicon in modern and ancient Chinese. -

Glottal Stop Initials and Nasalization in Sino-Vietnamese and Southern Chinese

Glottal Stop Initials and Nasalization in Sino-Vietnamese and Southern Chinese Grainger Lanneau A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2020 Committee: Zev Handel William Boltz Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2020 Grainger Lanneau University of Washington Abstract Glottal Stop Initials and Nasalization in Sino-Vietnamese and Southern Chinese Grainger Lanneau Chair of Supervisory Committee: Professor Zev Handel Asian Languages and Literature Middle Chinese glottal stop Ying [ʔ-] initials usually develop into zero initials with rare occasions of nasalization in modern day Sinitic1 languages and Sino-Vietnamese. Scholars such as Edwin Pullyblank (1984) and Jiang Jialu (2011) have briefly mentioned this development but have not yet thoroughly investigated it. There are approximately 26 Sino-Vietnamese words2 with Ying- initials that nasalize. Scholars such as John Phan (2013: 2016) and Hilario deSousa (2016) argue that Sino-Vietnamese in part comes from a spoken interaction between Việt-Mường and Chinese speakers in Annam speaking a variety of Chinese called Annamese Middle Chinese AMC, part of a larger dialect continuum called Southwestern Middle Chinese SMC. Phan and deSousa also claim that SMC developed into dialects spoken 1 I will use the terms “Sinitic” and “Chinese” interchangeably to refer to languages and speakers of the Sinitic branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family. 2 For the sake of simplicity, I shall refer to free and bound morphemes alike as “words.” 1 in Southwestern China today (Phan, Desousa: 2016). Using data of dialects mentioned by Phan and deSousa in their hypothesis, this study investigates initial nasalization in Ying-initial words in Southwestern Chinese Languages and in the 26 Sino-Vietnamese words. -

Ideophones in Middle Chinese

KU LEUVEN FACULTY OF ARTS BLIJDE INKOMSTSTRAAT 21 BOX 3301 3000 LEUVEN, BELGIË ! Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas'Van'Hoey' ' Presented(in(fulfilment(of(the(requirements(for(the(degree(of(( Master(of(Arts(in(Linguistics( ( Supervisor:(prof.(dr.(Jean=Christophe(Verstraete((promotor)( ( ( Academic(year(2014=2015 149(431(characters Abstract (English) Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas Van Hoey This M.A. thesis investigates ideophones in Tang dynasty (618-907 AD) Middle Chinese (Sinitic, Sino- Tibetan) from a typological perspective. Ideophones are defined as a set of words that are phonologically and morphologically marked and depict some form of sensory image (Dingemanse 2011b). Middle Chinese has a large body of ideophones, whose domains range from the depiction of sound, movement, visual and other external senses to the depiction of internal senses (cf. Dingemanse 2012a). There is some work on modern variants of Sinitic languages (cf. Mok 2001; Bodomo 2006; de Sousa 2008; de Sousa 2011; Meng 2012; Wu 2014), but so far, there is no encompassing study of ideophones of a stage in the historical development of Sinitic languages. The purpose of this study is to develop a descriptive model for ideophones in Middle Chinese, which is compatible with what we know about them cross-linguistically. The main research question of this study is “what are the phonological, morphological, semantic and syntactic features of ideophones in Middle Chinese?” This question is studied in terms of three parameters, viz. the parameters of form, of meaning and of use. -

The Fundamentals of Chinese Historical Phonology

ChinHistPhon – MA 1st yr Basics/ 1 Bartos The fundamentals of Chinese historical phonology 1. Old Mandarin (early modern Chinese; 14th c.) − 中原音韵 Zhongyuan Yinyun “Rhymes of the Central Plain”, written in 1324 by 周德清 Zhou Deqing: A pronunciation guide for writers and performers of 北曲 beiqu-verse in vernacular plays. − Arrangement: o 19 rhyme categories, each named with two characters, e.g. 真文, 江阳, 先天, 鱼模. o Within each rhyme category, words are divided according to tone category: 平声阴 平声阳 上声 去声 入声作 X 声 o Within each tone, words are divided into homophone groups separated by circles. o An appendix lists pairs of characters whose pronunciation is frequently confused, e.g.: 死有史 米有美 因有英 The 19 Zhongyuan Yinyun rhyme categories: Old Mandarin tones: The tone categories were the same as for modern standard Mandarin, except: − The former 入-tone words joined the other tone categories in a more regular fashion. ChinHistPhon – MA 1st yr Basics/ 2 Bartos 2. The reconstruction of the Middle Chinese sound system 2.1. Main sources 2.1.1. Primary – rhyme dictionaries, rhyme tables (Qieyun 切韵, Guangyun 广韵, …, Jiyun 集韵, Yunjing 韵镜, Qiyinlüe 七音略) – a comparison of modern Chinese dialects – shape of Chinese loanwords in ’sinoxenic’ languages (Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese) 2.1.2. Secondary – use of poetic devices (rhyming words, metric (= tonal patterns)) – transcriptions: - contemporary alphabetic transcription of Chinese names/words, e.g. Brahmi, Tibetan, … - contemporary Chinese transcription of foreign words/names of known origin ChinHistPhon – MA 1st yr Basics/ 3 Bartos – the content problem of the Qieyun: Is it some ‘reconstructed’ pre-Tang variety, or the language of the capital (Chang’an 长安), or a newly created norm, based on certain ‘compromises’? – the classic problem of ‘time-span’: Qieyun: 601 … Yunjing: 1161 → Pulleyblank: the Qieyun and the rhyme tables ( 等韵图) reflect different varieties (both geographically, and diachronically) → Early vs. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. These are also available as one exposure on a standard 35mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9 ’ black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information C om pany 300 North ZaeD Road. -

What Were the Four Divisions of Middle Chinese?

What were the four Divisions of Middle Chinese ? Michel Ferlus To cite this version: Michel Ferlus. What were the four Divisions of Middle Chinese ? . Diachronica, Netherlands: John Benjamins, 2009, 26 (2), pp.184-213. 10.1075/dia.26.2.02fer. halshs-01581138v2 HAL Id: halshs-01581138 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01581138v2 Submitted on 13 Nov 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License What were the four Divisions of Middle Chinese ? (updated version) Michel FERLUS Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, France The text presented here is the final result of a series of versions of our research on the four divisions (or grades) of ancient Chinese (Middle Chinese) : 1. (1998) Du chinois archaïque au chinois ancien : monosyllabisation et formation des syllabes tendu/lâche (Nouvelle théorie sur la phonétique historique du chinois), The 31st International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics, University of Lund, Swiden, Sept. 30th – Oct. 4th (22 pages). (Available: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00927220) 2. (2006) What were the four divisions (děng) of Middle Chinese ?, The 39th International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics, University of Washington, Seattle, September 15-17 (12 pages). -

The Dreaming Mind and the End of the Ming World

The Dreaming Mind and the End of the Ming World The Dreaming Mind and the End of the Ming World • Lynn A. Struve University of Hawai‘i Press Honolulu © 2019 University of Hawai‘i Press This content is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means that it may be freely downloaded and shared in digital format for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. Commercial uses and the publication of any derivative works require permission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Creative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. The open-access version of this book was made possible in part by an award from the James P. Geiss and Margaret Y. Hsu Foundation. Cover art: Woodblock illustration by Chen Hongshou from the 1639 edition of Story of the Western Wing. Student Zhang lies asleep in an inn, reclining against a bed frame. His anxious dream of Oriole in the wilds, being confronted by a military commander, completely fills the balloon to the right. In memory of Professor Liu Wenying (1939–2005), an open-minded, visionary scholar and open-hearted, generous man Contents Acknowledgments • ix Introduction • 1 Chapter 1 Continuities in the Dream Lives of Ming Intellectuals • 15 Chapter 2 Sources of Special Dream Salience in Late Ming • 81 Chapter 3 Crisis Dreaming • 165 Chapter 4 Dream-Coping in the Aftermath • 199 Epilogue: Beyond the Arc • 243 Works Cited • 259 Glossary-Index • 305 vii Acknowledgments I AM MOST GRATEFUL, as ever, to Diana Wenling Liu, head of the East Asian Col- lection at Indiana University, who, over many years, has never failed to cheerfully, courteously, and diligently respond to my innumerable requests for problematic materials, puzzlements over illegible or unfindable characters, frustrations with dig- ital databases, communications with publishers and repositories in China, etcetera ad infinitum. -

Bibliography of Chinese Linguistics William S.-Y.Wang

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF CHINESE LINGUISTICS WILLIAM S.-Y.WANG INTRODUCTION THIS IS THE FIRST LARGE-SCALE BIBLIOGRAPHY OF CHINESE LINGUISTICS. IT IS INTENDED TO BE OF USE TO STUDENTS OF THE LANGUAGE WHO WISH EITHER TO CHECK THE REFERENCE OF A PARTICULAR ARTICLE OR TO GAIN A PERSPECTIVE INTO SOME SPECIAL TOPIC OF RESEARCH. THE FIELD OF CHINESE LINGUIS- TICS HAS BEEN UNDERGOING RAPID DEVELOPMENT IN RECENT YEARS. IT IS HOPED THAT THE PRESENT WORK WILL NURTURE THIS DEVELOP- MENT BY PROVIDING A SENSE OF THE SIZABLE SCHOLARSHIP IN THE FIELD» BOTH PAST AND PRESENT. IN SPITE OF REPEATED CHECKS AND COUNTERCHECKS, THE FOLLOWING PAGES ARE SURE TO CONTAIN NUMEROUS ERRORS OF FACT, SELECTION AND OMISSION. ALSO» DUE TO UNEVENNESS IN THE LONG PROCESS OF SELECTION, THE COVERAGE HERE IS NOT UNIFORM. THE REPRESENTATION OF CERTAIN TOPICS OR AUTHORS IS PERHAPS NOT PROPORTIONAL TO THE EXTENT OR IMPORTANCE BIBLIOGRAPHY OF CHINESE LINGUISTICS ]g9 OF THE CORRESPONDING LITERATURE. THE COVERAGE CAN BE DIS- CERNED TO BE UNBALANCED IN TWO MAJOR WAYS. FIRST. THE EMPHASIS IS MORE ON-MODERN. SYNCHRONIC STUDIES. RATHER THAN ON THE WRITINGS OF EARLIER CENTURIES. THUS MANY IMPORTANT MONOGRAPHS OF THE QING PHILOLOGISTS. FOR EXAMPLE, HAVE NOT BEEN INCLUDED HERE. THOUGH THESE ARE CERTAINLY TRACE- ABLE FROM THE MODERN ENTRIES. SECOND, THE EMPHASIS IS HEAVILY ON THE SPOKEN LANGUAGE, ALTHOUGH THERE EXISTS AN ABUNDANT LITERATURE ON THE CHINESE WRITING SYSTEM. IN VIEW OF THESE SHORTCOMINGS, I HAD RESERVATIONS ABOUT PUBLISHING THE BIBLIOGRAPHY IN ITS PRESENT STATE. HOWEVER, IN THE LIGHT OF OUR EXPERIENCE SO FAR, IT IS CLEAR THAT A CONSIDERABLE AMOUNT OF TIME AND EFFORT IS STILL NEEDED TO PRODUCE A COMPREHENSIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY THAT IS AT ONCE PROPERLY BALANCED AMD COMPLETELY ACCURATE (AND, PERHAPS, WITH ANNOTATIONS ON THE IMPORTANT ENTRIES). -

“Regularities” and “Irregularities” in Chinese Historical Phonology

“Regularities” and “irregularities” in Chinese historical phonology Tianrang (Quain) Bu Honors Thesis Department of Anthropology Oberlin College April 2018 Advisor: Jason Haugen 1 ABSTRACT With a combination of methodologies from Western and Chinese traditional historical linguistics, this thesis is an attempt to survey and synthetically analyze the major sound changes in Chinese phonological history. It addresses two hypotheses – the Neogrammarian regularity hypothesis and the unidirectionality hypothesis – and tries to question their validity and applicability. Drawing from fourteen types of “regular” and “irregular” processes, the thesis argues that the origins and impetuses of sound change is far from just phonetic environment (“regular” changes) and lexical diffusion (“irregular” changes), and that sound change is not unidirectional because of the existence and significance of fortifying and bi/multidirectional changes. The thesis also examines the sociopolitical aspect of sound change through the discussion of language changes resulting from social, geographical and historical factors, suggesting that the study of sound change should be more interdisciplinary and miscellaneous in order to explain the phenomena more thoroughly and reach a better understanding of how human languages function both synchronically and diachronically. KEY WORDS: Chinese, historical, phonology, sound change 2 Table of contents List of abbreviations and keys…………………………………………………… 5 Index of tables and figures………………………………………………………. 8 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………… 10 2. Backgrounds………………………………………………………………….. 14 2.1. Overview of historical linguistics……………………………………………... 14 2.1.1. A brief history of historical linguistics………………………………………… 14 2.1.2. Neogrammarian regularity hypothesis and the comparative method………….. 16 2.1.3. Unidirectionality hypothesis and its application in phonology…………........... 19 2.2. Overview of historical Chinese phonology……………………………………. 21 2.2.1. -

Marjorie Chan's C6381. History of the Chinese Language (Autumn

[ Gen. Info | Txtbks | Desc. | Stud. Resp. | Grading | Sched. | Readings | Suppl. Rdgs | Web ] Enter Site Search Go! AUTUMN SEMESTER 2012 CHINESE 6381 History of the Chinese Language Professor Marjorie K.M. Chan Dept. of East Asian Langs. & Lits. The Ohio State University Columbus, OH 43210 U.S.A. __________________________________________________________________________________ COURSE: Chinese 6381. History of the Chinese Language Class No. & Credit Hours: 16626 3 units G Prerequisites: Chinese 680 or 6380, or permission of instructor. Not open to students with credit for Chinese 681. Course page: http://people.cohums.ohio-state.edu/chan9/c6381.htm TIME & PLACE: T R 12:45 - 2:05 p.m. N044 Scott Laboratory (Building 148, 201 W. 19th Avenue) (multimedia classroom) OFFICE HOURS: R 2:15 - 3:45 p.m., or by appointment Office: 362 Hagerty Hall (1775 College Road) Tel: 292.3619 (292.5816 for messages, 292.3225 for faxes) E-mail: chan.9 osu.edu MC's Home Page: people.cohums.ohio-state.edu/chan9 MC's ChinaLinks: ChinaLinks.osu.edu __________________________________________________________________________________ TEXTBOOKS 1. Jerry Norman. 1988. Chinese. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge U. Press. [ISBN: 0-521-29653-6 (pbk)] Required. Available from SBX (1806 N. High Street, (Tel) 291.9528). (Note: OSU Libraries has a copy of the textbook, and it used to have Huiying Zhang's Chinese translation of it.) 2. Edwin G. Pulleyblank (1995). Outline of Classical Chinese Grammar. Paperback. Vancouver: U. of British Columbia Press. [ISBN: 0-7748-0541-2 (pbk) Optional purchase. Available from SBX. (Note: OSU Libraries has a copy of the textbook as well as Jingtao Sun's Chinese translation of it.) 1 3.