Section 508 Self-Evaluation: Web Page Accessibility Questionnaire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Wide Web: Introduzione E Componenti

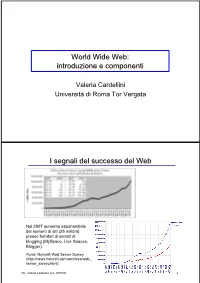

World Wide Web: introduzione e componenti Valeria Cardellini Università di Roma Tor Vergata I segnali del successo del Web Nel 2007 aumento esponenziale del numero di siti (25 milioni) presso fornitori di servizi di blogging (MySpace, Live Spaces, Blogger) Fonte: Netcraft Web Server Survey (http://news.netcraft.com/archives/web_ server_survey.html) IW - Valeria Cardellini, A.A. 2007/08 2 I segnali del successo del Web (2) • Fino all’introduzione dei sistemi P2P, il Web è stata l’applicazione killer di Internet (75% del traffico di Internet nel 1998) Event Period Peak day Peak minute NCSA server (Oct. 1995) - 2 Million - Olympic Summer Games 192 Million 8 Million - (Aug. 1996) (17 days) Nasa Pathfinder 942 Million 40 Million - (July 1997) (14 days) Olympic Winter Games 634.7 Million 55 Million 110,000 (Feb. 1998) (16 days) Wimbledon (July 1998) - - 145,000 FIFA World Cup 1,350 Million 73 Million 209,000 (July 1998) (84 days) Wimbledon (July 1999) - 125 Million 430,000 Wimbledon (July 2000) - 282 Million 964,000 Olympic Summer Games - 875 Million 1,200,000 (Sept. 2000) [Carico misurato in contatti] • Inoltre: google.com, msn.com, yahoo.com (> 200 milioni di contatti al giorno) IW - Valeria Cardellini, A.A. 2007/08 3 I motivi alla base del successo del Web • Digitalizzazione dell’informazione – Qualsiasi informazione rappresentabile in binario come sequenza di 0 e 1 • Diffusione di Internet (dagli anni 1970) – Trasporto dell’informazione ovunque, in tempi rapidissimi e a costi bassissimi • Diffusione dei PC (dagli anni 1980) – Accesso, memorizzazione ed elaborazione dell’informazione da parte di chiunque a costi bassissimi • Semplicità di utilizzo e trasparenza dell’allocazione delle risorse – Semplicità di utilizzo mediante l’uso di interfacce grafiche IW - Valeria Cardellini, A.A. -

MHCC Accessibility Conformance Report

Mt. Hood Community College Website Accessibility Conformance Report WCAG Edition VPAT® Version 2.3 (Revised) – April 2019 Name of Product/Version: www.mhcc.edu Product Description: MHCC Main Website Report Date: August 2, 2019 Contact Information: Tristan Price – [email protected] Notes: Evaluation Methods Used: IAAP WAS Testing Methodology, SiteImprove, Manual Testing __________________________________ “Voluntary Product Accessibility Template” and “VPAT” are registered service marks of the Information Technology Industry Council (ITI) Page 1 of 5 Applicable Standards/Guidelines This report covers the degree of conformance for the following accessibility standard/guidelines: Standard/Guideline Included In Report Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0 Level A (Yes / No ) Level AA (Yes / No ) Level AAA (Yes / No ) Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1 Level A (Yes / No ) Level AA (Yes / No ) Level AAA (Yes / No ) Terms The terms used in the Conformance Level information are defined as follows: • Supports: The functionality of the product has at least one method that meets the criterion without known defects or meets with equivalent facilitation. • Partially Supports: Some functionality of the product does not meet the criterion. • Does Not Support: The majority of product functionality does not meet the criterion. • Not Applicable: The criterion is not relevant to the product. • Not Evaluated: The product has not been evaluated against the criterion. This can be used only in WCAG 2.0 Level AAA. WCAG 2.x Report Note: When reporting on conformance with the WCAG 2.x Success Criteria, they are scoped for full pages, complete processes, and accessibility-supported ways of using technology as documented in the WCAG 2.0 Conformance Requirements. -

HTTP Cookie - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 14/05/2014

HTTP cookie - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 14/05/2014 Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search HTTP cookie From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Navigation A cookie, also known as an HTTP cookie, web cookie, or browser HTTP Main page cookie, is a small piece of data sent from a website and stored in a Persistence · Compression · HTTPS · Contents user's web browser while the user is browsing that website. Every time Request methods Featured content the user loads the website, the browser sends the cookie back to the OPTIONS · GET · HEAD · POST · PUT · Current events server to notify the website of the user's previous activity.[1] Cookies DELETE · TRACE · CONNECT · PATCH · Random article Donate to Wikipedia were designed to be a reliable mechanism for websites to remember Header fields Wikimedia Shop stateful information (such as items in a shopping cart) or to record the Cookie · ETag · Location · HTTP referer · DNT user's browsing activity (including clicking particular buttons, logging in, · X-Forwarded-For · Interaction or recording which pages were visited by the user as far back as months Status codes or years ago). 301 Moved Permanently · 302 Found · Help 303 See Other · 403 Forbidden · About Wikipedia Although cookies cannot carry viruses, and cannot install malware on 404 Not Found · [2] Community portal the host computer, tracking cookies and especially third-party v · t · e · Recent changes tracking cookies are commonly used as ways to compile long-term Contact page records of individuals' browsing histories—a potential privacy concern that prompted European[3] and U.S. -

Tecnologias Da Informação E Comunicação Vs Exclusão Social

Instituto Superior de Engenharia do Porto Departamento de Engenharia Informática Ramo de Computadores e Sistemas Projecto 5º Ano Tecnologias da Informação e Comunicação vs Exclusão Social Autor/Número Sérgio Francisco dos Santos Morais / 990348 Orientador Dr. Constantino Martins Porto, Setembro de 2004 Agradecimentos “Não há no mundo exagero mais belo que a gratidão” La Bruyère (escritor francês 1645-1695) Aproveito este espaço para agradecer a todas as pessoas que directamente ou indirectamente contribuíram e me ajudaram na elaboração deste projecto, pelo seu apoio e incentivo, com um agradecimento especial: ü Ao meu orientador Dr. Constantino Martins, pelo interesse, ajuda e apoio que me prestou. Pela disponibilidade que teve para esclarecimento de dúvidas que foram surgindo e para a revisão das diversas versões do projecto; ü Ao Eng.º Paulo Ferreira pela ajuda que me deu na parte final do projecto; ü Ao Eng.º Carlos Vaz de Carvalho pela autorização concedida para a entrega dos inquéritos aos alunos. Pela revisão do inquérito e pelas suas sugestões; ü À Eng.ª Bertil Marques e ao Eng.º António Costa pela entrega e recolha dos inquéritos aos seus alunos; ü Aos alunos que preencheram os inquéritos; ü À minha família e amigos pela motivação e incentivo que me deram e pela paciência que tiveram para suportar dias e noites sem a minha atenção. A todos o meu muito obrigado. I Resumo Vivemos numa sociedade cada vez mais tecnológica, em que as Tecnologias de Informação e Comunicação (TIC) tem um papel importante e decisivo. As TIC fazem parte integrante do nosso quotidiano ao ponto de ser quase impossível viver sem elas. -

Learning Technology Supplement Support

Welcome to this special issue of the Learning Technol- ogy supplement. This issue highlights new legislation Learning coming into force in September which has major impli- cations for any staff who publish information on the Web. Staff from many departments and teams have contributed to this issue and thanks are extended to all Technology of them for their contributions, comments, advice and BITs Learning Technology Supplement support. Number Eight: June 2002 8 Why do you want a website anyway? New legislation (see page 2) has major implications for any staff involved in producing Web pages. All staff involved in Web publishing should review their pages in the light of this legislation. Information seminars (see back page) are to be held on 12th June. Although this supplement focuses on making your website as accessible as possible, there is no point having a fully accessible, attractive website if it has no real purpose and if your students or target users don’t ever visit it. Before you go to the bother and effort of building a website, stop for a moment and ask yourself a couple of questions: “Who is this website for?” and “What is the user supposed to gain from using this site?” Websites can have many purposes, from attracting potential students to your course to publicising your excellent research activities. They can be used to provide up-to-date information or to act as a resource base or to give the students a self study centre, or… Whatever your reason, it has to be clear and appropriate for your users. -

The Influence of Assistive Technology on Students with Disability: a Review

SRJIS/BIMONTHLY / DR. B. S. PARIMAL (375-393) THE INFLUENCE OF ASSISTIVE TECHNOLOGY ON STUDENTS WITH DISABILITY: A REVIEW B. S. Parimal, Ph. D. Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology, the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda Abstract The 21st century is known as century of Technology and the aim of technology is to improve the lives of human beings. Assistive Technology can be defined as equipment and software that are used to maintain or improve the functional capabilities of person with a disability. Technological innovation has dramatically altered the landscape of both preventive and therapeutic approaches to students with disability. Assistive Technology interventions measurably enhance students with learning disabilities immediate and long-term academicals performances. Assistive Technology play significant role in prevention and treatment of students with disability. Technical innovation has had a dramatic impact on a central arena of primary disability prevention: the reduction of serious, disabling injuries in children. In general, children with disabilities rely more heavily than other children on technical interventions, including medications, specialized medical and educational services, and a variety of assistive devices. Childhood disability cannot be fully understood without a clear appreciation for the power and machinery of technical innovation in the modern world. Technical progress in both preventive and therapeutic interventions is constantly reshaping the character and prevalence of students with disability and therefore its essential challenge to both the health and education communities. Computer technology has the potential to act as an equalizer by freeing many students from their disabilities in a way that allows them to achieve their true potential. The results reflected an improvement in student achievement as well as an increase in their attitudes about the use of the technology. -

Santana Vagnerfigueredode M.Pdf

i ii iii Instituto de Computa¸c˜ao Universidade Estadual de Campinas Identifica¸c˜ao de Padr˜oes de Utiliza¸c˜ao da Web Mediada por Tecnologias Assistivas Vagner Figuerˆedo de Santana1 Abril de 2009 Banca Examinadora: • Profa. Dra. Maria Cec´ılia Calani Baranauskas Instituto de Computa¸c˜ao - UNICAMP (Orientadora) • Profa. Dra. Renata Pontin de Mattos Fortes Instituto de Ciˆencias Matem´aticas e de Computa¸c˜ao - Universidade de S˜ao Paulo • Prof. Dr. Hans Kurt Edmund Liesenberg Instituto de Computa¸c˜ao - UNICAMP • Prof. Dr. Ismar Frango Silveira (Suplente) Faculdade de Computa¸c˜ao e Inform´atica - Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie • Prof. Dr. Rog´erio Drummond Burnier Pessoa de Mello Filho (Suplente) Instituto de Computa¸c˜ao - UNICAMP 1Suporte financeiro do projeto PROESP/CAPES v Resumo A Web conta com dezenas de milh˜oes de websites, mas poucos deles est˜ao em conformidade com requisitos simples de acessibilidade, como utilizar tamanhos relativos ou descrever elementos gr´aficos, o que pode indicar problemas de design de Interface de Usu´ario (IU). Para se identificar este tipo de problema utiliza-se avalia¸c˜ao do c´odigo de websites. No entanto, outros problemas surgem apenas durante a intera¸c˜ao do usu´ario com a IU. Sem considerar dados resultantes do uso, problemas de usabilidade e/ou barreiras de acessibi- lidade podem permanecer desconhecidos. Portanto, identificar como usu´arios interagem com IUs ´euma forma de detectar problemas de design e descobrir maneiras de utiliza¸c˜ao diferentes das previstas durante o projeto de IU. Entre as maneiras de capturar a intera¸c˜ao do usu´ario com IUs est˜ao a utiliza¸c˜ao de v´ıdeos, captura dos movimentos dos olhos do usu´ario, etc. -

Empresas Podem Fazer Pela Inclusão Digital

O QUE AS EMPRESAS PODEM FAZER PELA INCLUSÃO DIGITAL Renato Cruz O Que as Empresas Podem Fazer pela Inclusão Digital é uma publicação do Instituto Ethos, distribuída gratuitamente aos seus associados. Realização Instituto Ethos de Empresas e Responsabilidade Social Rua Francisco Leitão, 469 - 14º andar, conj, 1407 Pinheiros - 05414-020, SP Tel. (11) 3897-2400 www.ethos.org.br Patrocínio Sadia, ALSTOM Autoria Renato Cruz Colaboradores do Instituto Ethos Benjamin Gonçalves, Carlos Adriano Silva, Carmen Weingrill, Fernando Pachi (coordenação), Leno F. Silva, Mateus Cozer, Paulo Itacarambi Colaboradores Cristina De Luca, Daniel Marinho e Ethevaldo Siqueira Redação Renato Cruz Revisão Ana Maria Barbosa Projeto e produção gráfica Planeta Terra Design (Waldemar Zaidler e William Haruo) Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) (Câmara Brasileira do Livro, SP, Brasil) Cruz, Renato O que as empresas podem fazer pela inclusão digital / Renato Cruz — São Paulo : Instituto Ethos, 2004 ISBN 85-88046-15-6 Vários Colaboradores. Bibliografia. 1. Empresas - Responsabilidade Social 2. Tecnologia da informação I. Título. 04-1504 CDD-303.4833 Índices para catálogo sistemático: 1. Inclusão digital : Tecnologia da informação e comunicação : Aspectos sociais 303.4833 Tiragem: 7.000 exemplares São Paulo, março de 2004. É permitida a reprodução desta publicação, desde que citada a fonte e com autorização prévia do Instituto Ethos. Esclarecimentos importantes sobre as atividades do Instituto Ethos: 1. O trabalho de orientação às empresas é voluntário, sem nenhuma cobrança ou remuneração. 2. Não fazemos consultoria e não credenciamos nem autorizamos profissionais a oferecer qualquer tipo de serviço em nosso nome. 3. Não somos entidade certificadora de responsabilidade social nem fornecemos “selo” com essa função. -

Intro to Various Aspects of Low Vision We

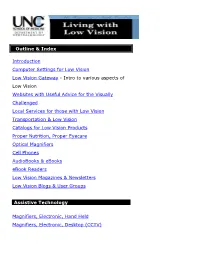

Outline & Index Introduction Computer Settings for Low Vision Low Vision Gateway - Intro to various aspects of Low Vision Websites with Useful Advice for the Visually Challenged Local Services for those with Low Vision Transportation & Low Vision Catalogs for Low Vision Products Proper Nutrition, Proper Eyecare Optical Magnifiers Cell Phones AudioBooks & eBooks eBook Readers Low Vision Magazines & Newsletters Low Vision Blogs & User Groups Assistive Technology Magnifiers, Electronic, Hand Held Magnifiers, Electronic, Desktop (CCTV) Magnifier Software for the Computer Screen Magnifiers for the Web Browser Low Vision Web Browsers Text to Speech Screen Readers, Software for Computers Scan to Speech Conversion Speech to Text Conversion, Speech Recognition The Macintosh The Apple Macintosh & its Special Strengths Mac Universal Access Commands Magnifiers for the Macintosh Text to Speech Screen Readers for Macintoshes Speech Recognition for Macs Financial Aid for Assistive Technology AudioBooks & eBooks Audiobooks are read to you by a recorded actor. eBooks allow you to download the book, magnify the type size and have the computer read to you out loud. Free Online eBooks • Online Books http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/ • Gutenberg Project http://www.gutenberg.net/index.php • Net Library – 24,000 eBooks & 2,000 eAudiobooks. Sign up thru your public library, then sign on to NC Live, and finally to Net Library. http://netlibrary.com/Centers/AudiobookCenter/Browse .aspx?Category=Lectures Free Online Audiobooks • http://librivox.org/newcatalog/search.php?title=&aut hor=&status=complete&action=Search • http://www.audiobooksforfree.com/ Books on CD & cassette North Carolina Library for the Blind (see above) http://statelibrary.dcr.state.nc.us/lbph/lbph.htm Downloadable Talking Books for the Blind https://www.nlstalkingbooks.org/dtb/ Audible.com. -

Assistive Technology

A Guide to Assistive Technology To Support Literacy Learners With Disabilities NWT Literacy Council Yellowknife, NT Assistive Technology for Literacy Learners 2 NWT Literacy Council Assistive Technology for Literacy Learners Table of Contents Acknowledgements .........................................................................6 What is Assistive Technology? .........................................................7 Things to keep in mind when using Assistive Technology .................8 How to use the Guide .......................................................................9 Reading Printed and Electronic Material ........................................10 JAWS for Windows.....................................................................................................................................11 ZoomText with Speech..............................................................................................................................12 MAGic for Windows..................................................................................................................................13 CCTV (Closed Circuit Television)...........................................................................................................14 Victor Reader VIBE ...................................................................................................................................15 Victor Reader Soft.......................................................................................................................................16 -

IBM Home Page Reader for Windows Version 3.0 — the Voice of the World Wide Web

Software Announcement October 17, 2000 IBM Home Page Reader for Windows Version 3.0 — The Voice of the World Wide Web Overview Key Prerequisites At a Glance IBM Home Page Reader for Minimum System Requirements Windows Version 3.0, an IBM Home Page Reader Version 3.0 is Independence Series product, • Microsoft Windows 98, a spoken Web browser that provides spoken Web access for Windows 2000, or Windows provides access to the Internet and blind and visually impaired users. Millennium. electronic mail for blind, visually impaired, and reading-challenged By combining the capabilities of • Microsoft Internet Explorer V5.0. IBM′s text-to-speech synthesizer and individuals. It features: • Internet Explorer, Home Page Processor: Equivalent to an • Reader reads aloud Web-based Intel Pentium 233 MHz Stand-alone assistive technology to access the information just as it is presented on processor and 256K L2 cache (or ′ the computer screen. The full range equivalent). Internet, using IBM s of Web information is provided in a text-to-speech engine • 48 MB RAM for logical, clear, and comprehensive • Automatic Web page language manner. The power and robust Windows 98/Millennium, and 64 MB RAM for Windows 2000. detection in up to seven features of Home Page Reader languages in selected language enable blind or visually impaired • Hard Disk Space: 80 MB of versions users to quickly and independently available hard disk space for • view TV listings, read newspapers, Home Page Reader. For Internet Integrated Web server and place online orders, search the Explorer 5.0, the minimal e-mail functions Internet, e-mail family and friends, installation (browser only) • Voice and visual and even read Web pages in requires 45 MB for installation, synchronization of graphic, text, different languages. -

L'usabilitat De Llocs Web Per a Persones Amb Discapacitat

Juny 2004 Estudis E.T. Informàtica de sistemes Treball Final de Carrera L’usabilitat de llocs web per a persones amb discapacitat Universitat Oberta de Catalunya Treball fi de carrera: L’usabilitat de llocs web per a persones amb discapacitat Alumne: Lluís Gallego Ruestes ([email protected]) Consultor: Josep M. Flix Rovira ([email protected]) L’usabilitat de llocs web per a persones amb discapacitat L’usabilitat de llocs web per a persones amb discapacitat Aquest Treball intenta donar una visió global de la problemàtica de l’accessibilitat web. Com quasi bé tot problema té solucions. El producte que produeix o pot produir la problemàtica és una pàgina web i els afectats són les persones amb alguna discapacitat. Aleshores al Treball s’estudia l’usabilitat d’una pàgina web orientada a uns usuaris especials i per tant es revisarà l’accessibilitat de la pàgina. Per tant he considerat necessari mostrar els conceptes d’usabilitat i accessibilitat com pas inicial. A continuació el món dels usuaris afectats en la problemàtica de l’accessibilitat web, persones amb discapacitat. Un cop assabentat de què és el que s’ha de revisar i quin serà l’usuari destinatari del producte avaluat he considerat bàsic conèixer les normatives sota les quals s’ha d’avaluar el producte, la pàgina web. Les normatives WAI formen unes recomanacions del consorci W3C. Aleshores he presentat les Pautes WAI tot i què d’una forma resumida i introductòria. El nucli fonamental del Treball està construït sobre la Metodologia que ha d’avaluar el compliment de les recomanacions de la W3C.