Soil-Transmitted Helminths

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trichinosis (Trichinellosis) Case Reporting and Investigation Protocol

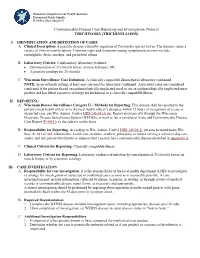

Wisconsin Department of Health Services Division of Public Health P-01912 (Rev 08/2017) Communicable Disease Case Reporting and Investigation Protocol TRICHINOSIS (TRICHINELLOSIS) I. IDENTIFICATION AND DEFINITION OF CASES A. Clinical Description: A parasitic disease caused by ingestion of Trichinella species larvae. The disease causes a variety of clinical manifestations. Common signs and symptoms among symptomatic persons include eosinophilia, fever, myalgia, and periorbital edema. B. Laboratory Criteria: Confirmatory laboratory evidence: • Demonstration of Trichinella larvae on muscle biopsy, OR • A positive serology for Trichinella. C. Wisconsin Surveillance Case Definition: A clinically compatible illness that is laboratory confirmed. NOTE: In an outbreak setting, at least one case must be laboratory confirmed. Associated cases are considered confirmed if the patient shared an epidemiologically implicated meal or ate an epidemiologically implicated meat product and has either a positive serology for trichinosis or a clinically compatible illness. II. REPORTING A. Wisconsin Disease Surveillance Category II – Methods for Reporting: This disease shall be reported to the patient’s local health officer or to the local health officer’s designee within 72 hours of recognition of a case or suspected case, per Wis. Admin. Code § DHS 145.04 (3) (b). Report electronically through the Wisconsin Electronic Disease Surveillance System (WEDSS), or mail or fax a completed Acute and Communicable Disease Case Report (F-44151) to the address on the form. B. Responsibility for Reporting: According to Wis. Admin. Code § DHS 145.04(1), persons licensed under Wis. Stat. ch. 441 or 448, laboratories, health care facilities, teachers, principals, or nurses serving a school or day care center, and any person who knows or suspects that a person has a communicable disease identified in Appendix A. -

Onchocerciasis

11 ONCHOCERCIASIS ADRIAN HOPKINS AND BOAKYE A. BOATIN 11.1 INTRODUCTION the infection is actually much reduced and elimination of transmission in some areas has been achieved. Differences Onchocerciasis (or river blindness) is a parasitic disease in the vectors in different regions of Africa, and differences in cause by the filarial worm, Onchocerca volvulus. Man is the the parasite between its savannah and forest forms led to only known animal reservoir. The vector is a small black fly different presentations of the disease in different areas. of the Simulium species. The black fly breeds in well- It is probable that the disease in the Americas was brought oxygenated water and is therefore mostly associated with across from Africa by infected people during the slave trade rivers where there is fast-flowing water, broken up by catar- and found different Simulium flies, but ones still able to acts or vegetation. All populations are exposed if they live transmit the disease (3). Around 500,000 people were at risk near the breeding sites and the clinical signs of the disease in the Americas in 13 different foci, although the disease has are related to the amount of exposure and the length of time recently been eliminated from some of these foci, and there is the population is exposed. In areas of high prevalence first an ambitious target of eliminating the transmission of the signs are in the skin, with chronic itching leading to infection disease in the Americas by 2012. and chronic skin changes. Blindness begins slowly with Host factors may also play a major role in the severe skin increasingly impaired vision often leading to total loss of form of the disease called Sowda, which is found mostly in vision in young adults, in their early thirties, when they northern Sudan and in Yemen. -

CDC Overseas Parasite Guidelines

Guidelines for Overseas Presumptive Treatment of Strongyloidiasis, Schistosomiasis, and Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections for Refugees Resettling to the United States U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases Division of Global Migration and Quarantine February 6, 2019 Accessible version: https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/guidelines/overseas/intestinal- parasites-overseas.html 1 Guidelines for Overseas Presumptive Treatment of Strongyloidiasis, Schistosomiasis, and Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections for Refugees Resettling to the United States UPDATES--the following are content updates from the previous version of the overseas guidance, which was posted in 2008 • Latin American and Caribbean refugees are now included, in addition to Asian, Middle Eastern, and African refugees. • Recommendations for management of Strongyloides in refugees from Loa loa endemic areas emphasize a screen-and-treat approach and de-emphasize a presumptive high-dose albendazole approach. • Presumptive use of albendazole during any trimester of pregnancy is no longer recommended. • Links to a new table for the Treatment Schedules for Presumptive Parasitic Infections for U.S.-Bound Refugees, administered by IOM. Contents • Summary of Recommendations • Background • Recommendations for overseas presumptive treatment of intestinal parasites o Refugees originating from the Middle East, Asia, North Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean o Refugees -

STUDY of PARASITIC INFESTATION and ITS EFFECT on the HEALTH STATUS of PRIMARY SCHOOL CHILDREN in TANTA CITY Nour Abd El Azize Mohammed Mealy, Prof

STUDY OF PARASITIC INFESTATION AND ITS EFFECT ON THE HEALTH STATUS OF PRIMARY SCHOOL CHILDREN IN TANTA CITY Nour Abd El Azize Mohammed Mealy, Prof. Dr. Nadia Yahia Ismaiel, Prof. Dr. Hassan Saad Abu Saif, Prof. Dr. Wael Refaat Hablas STUDY OF PARASITIC INFESTATION AND ITS EFFECT ON THE HEALTH STATUS OF PRIMARY SCHOOL CHILDREN IN TANTA CITY By Nour Abd El Azize Mohammed Mealy, Prof. Dr. Nadia Yahia Ismaiel*, Prof. Dr. Hassan Saad Abu Saif*, Prof. Dr. Wael Refaat Hablas** Pediatric*& Clinical Pathology** Depts. Al-Azhar University- Faculty of Medicine ABSTRACT Background: School age children are one of the groups at high-risk for intestinal parasitic infestations. Factors like poor developments of hygienic habits, immune system and over-crowding contributes for infestation. The adverse effects of intestinal parasites among children are diverse and alarming. Intestinal parasitic infestations have detrimental effects on the survival, appetite, growth and physical fitness, school attendance and cognitive performance of school age children (Alemu et al., 2011). Objectives: We aimed to 1. Assess the prevalence of parasitic infestation and its effect on the health status of primary school children in Tanta City (5 schools from 3 areas at Tanta city) 2. Determine the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infestation among primary school children in some urban communities of Tanta City 3. Identify associated risk factors of school children for parasitic infestations in some urban communities of Tanta City. Design: This is descriptive cross sectional study that was carried out on 1000 students (boys &girls) at governmental primary schools at Tanta rural areas. This research was continued until fulfillment of the study from April 2017 to May 2018. -

Public Health Significance of Intestinal Parasitic Infections*

Articles in the Update series Les articles de la rubrique give a concise, authoritative, Le pointfournissent un bilan and up-to-date survey of concis et fiable de la situa- the present position in the tion actuelle dans les do- Update selectedfields, coveringmany maines consideres, couvrant different aspects of the de nombreux aspects des biomedical sciences and sciences biomedicales et de la , po n t , , public health. Most of santepublique. Laplupartde the articles are written by ces articles auront donc ete acknowledged experts on the redigeis par les specialistes subject. les plus autorises. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 65 (5): 575-588 (1987) © World Health Organization 1987 Public health significance of intestinal parasitic infections* WHO EXPERT COMMITTEE' Intestinal parasitic infections are distributed virtually throughout the world, with high prevalence rates in many regions. Amoebiasis, ascariasis, hookworm infection and trichuriasis are among the ten most common infections in the world. Other parasitic infections such as abdominal angiostrongyliasis, intestinal capil- lariasis, and strongyloidiasis are of local or regional public health concern. The prevention and control of these infections are now more feasible than ever before owing to the discovery of safe and efficacious drugs, the improvement and sim- plification of some diagnostic procedures, and advances in parasite population biology. METHODS OF ASSESSMENT The amount of harm caused by intestinal parasitic infections to the health and welfare of individuals and communities depends on: (a) the parasite species; (b) the intensity and course of the infection; (c) the nature of the interactions between the parasite species and concurrent infections; (d) the nutritional and immunological status of the population; and (e) numerous socioeconomic factors. -

Presumptive Treatment and Screening for Stronglyoidiasis, Infections

Presumptive Treatment and Screening for Strongyloidiasis, Infections Caused by Other Soil- Transmitted Helminths, and Schistosomiasis Among Newly Arrived Refugees U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases Division of Global Migration and Quarantine November 26, 2018 Accessible link: https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/guidelines/domestic/intestinal-parasites- domestic.html Introduction Strongyloides parasites, other soil-transmitted helminths (STH), and Schistosoma species are some of the most common infections among refugees [1, 2]. Among refugees resettled in North America, the prevalence of potentially pathogenic parasites ranges from 8% to 86% [1, 2]. This broad range may be explained by differences in geographic origin, age, previous living and environmental conditions, diet, occupational history, and education level. Although frequently asymptomatic or subclinical, some infections may cause significant morbidity and mortality. Parasites that infect humans represent a complex and broad category of organisms. This section of the guidelines will provide detailed information regarding the most commonly encountered parasitic infections. A summary table of current recommendations is included in Table 1. In addition, information on overseas pre-departure intervention programs can be accessed on the CDC Immigrant, Refugee, and Migrant Health website. Strongyloides Below is a brief summary of salient points about Strongyloides infection in refugees, especially in context of the presumptive treatment with ivermectin. Detailed information about Strongyloides for healthcare providers can be found at the CDC Parasitic Diseases website. Background • Ivermectin is the drug of choice for strongyloidiasis. CDC presumptive overseas ivermectin treatment was initiated in 2005. Epidemiology • Prevalence in serosurveys of refugee populations ranges from 25% to 46%, with a particularly high prevalence in Southeast Asian refugees [2-4]. -

Performance of Two Serodiagnostic Tests for Loiasis in A

Performance of two serodiagnostic tests for loiasis in a Non-Endemic area Federico Gobbi, Dora Buonfrate, Michel Boussinesq, Cédric Chesnais, Sébastien Pion, Ronaldo Silva, Lucia Moro, Paola Rodari, Francesca Tamarozzi, Marco Biamonte, et al. To cite this version: Federico Gobbi, Dora Buonfrate, Michel Boussinesq, Cédric Chesnais, Sébastien Pion, et al.. Perfor- mance of two serodiagnostic tests for loiasis in a Non-Endemic area. PLoS Neglected Tropical Dis- eases, Public Library of Science, 2020, 14 (5), pp.e0008187. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008187. inserm- 02911633 HAL Id: inserm-02911633 https://www.hal.inserm.fr/inserm-02911633 Submitted on 4 Aug 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. PLOS NEGLECTED TROPICAL DISEASES RESEARCH ARTICLE Performance of two serodiagnostic tests for loiasis in a Non-Endemic area 1 1 2 2 Federico GobbiID *, Dora Buonfrate , Michel Boussinesq , Cedric B. Chesnais , 2 1 1 1 3 Sebastien D. Pion , Ronaldo Silva , Lucia Moro , Paola RodariID , Francesca Tamarozzi , Marco Biamonte4, Zeno Bisoffi1,5 1 IRCCS Sacro -

Public Health Significance of Foodborne

imental er Fo p o x d E C Journal of Experimental Food f h o e l m a n i Pal et al., J Exp Food Chem 2018, 4:1 s r t u r y o J Chemistry DOI: 10.4172/2472-0542.1000135 ISSN: 2472-0542 Review Article Open Access Public Health Significance of Foodborne Helminthiasis: A Systematic Review Mahendra Pal1*, Yodit Ayele2, Angesom Hadush3, Pooja Kundu4 and Vijay J Jadhav4 1Narayan Consultancy on Veterinary Public Health, 4 Aangan, Jagnath Ganesh Dairy Road, Anand-38001, India 2Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Bonga University, Post Box No.334, Bonga, Ethiopia 3Department of Animal Production and Technology, College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, Adigrat University, P.O. Box 50, Adigrat, Ethiopia 4Department of Veterinary Public Health and Epidemiology, College of Veterinary Sciences, LUVAS, Hisar-125004, India *Corresponding author: Mahendra Pal, Narayan Consultancy on Veterinary Public Health and Microbiology, 4 Aangan, Jagnath Ganesh Dairy Road, Anand-388001, Gujarat, India, E-mail: [email protected] Received date: December 18, 2017; Accepted date: January 19, 2018; Published date: January 25, 2018 Copyright: ©2017 Pal M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Foodborne diseases, caused by biological as well as chemical agents, have an impact in both developing and developed nations. The foodborne diseases of microbial origin are acute where as those caused by chemical toxicants are resulted due to chronic exposure. -

Imaging Parasitic Diseases

Insights Imaging (2017) 8:101–125 DOI 10.1007/s13244-016-0525-2 REVIEW Unexpected hosts: imaging parasitic diseases Pablo Rodríguez Carnero1 & Paula Hernández Mateo2 & Susana Martín-Garre2 & Ángela García Pérez3 & Lourdes del Campo1 Received: 8 June 2016 /Revised: 8 September 2016 /Accepted: 28 September 2016 /Published online: 23 November 2016 # The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Radiologists seldom encounter parasitic dis- • Some parasitic diseases are still endemic in certain regions eases in their daily practice in most of Europe, although in Europe. the incidence of these diseases is increasing due to mi- • Parasitic diseases can have complex life cycles often involv- gration and tourism from/to endemic areas. Moreover, ing different hosts. some parasitic diseases are still endemic in certain • Prompt diagnosis and treatment is essential for patient man- European regions, and immunocompromised individuals agement in parasitic diseases. also pose a higher risk of developing these conditions. • Radiologists should be able to recognise and suspect the This article reviews and summarises the imaging find- most relevant parasitic diseases. ings of some of the most important and frequent human parasitic diseases, including information about the para- Keywords Parasitic diseases . Radiology . Ultrasound . site’s life cycle, pathophysiology, clinical findings, diag- Multidetector computed tomography . Magnetic resonance nosis, and treatment. We include malaria, amoebiasis, imaging toxoplasmosis, trypanosomiasis, leishmaniasis, echino- coccosis, cysticercosis, clonorchiasis, schistosomiasis, fascioliasis, ascariasis, anisakiasis, dracunculiasis, and Introduction strongyloidiasis. The aim of this review is to help radi- ologists when dealing with these diseases or in cases Parasites are organisms that live in another organism at the where they are suspected. -

Eosinophilic Cellulitis Secondary to Occult Strongyloidiasis, Case Report

6 Case Report Page 1 of 6 Eosinophilic cellulitis secondary to occult strongyloidiasis, case report Llewelyn Yi Chang Tan, Dingyuan Wang, Joyce Siong See Lee, Benjamin Wen Yang Ho, Joel Hua Liang Lim National Skin Centre, Singapore, Singapore Correspondence to: Llewelyn Yi Chang Tan, MBChB. National Skin Centre, Singapore, Singapore. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Eosinophilic cellulitis (EC), also known as Wells syndrome, is a rare reactive inflammatory dermatosis which may masquerade as bacterial cellulitis. A 59-year-old gentleman who presented with an acute onset of pruritic rashes affecting the chest and abdomen, along with painful induration over bilateral lower limbs, in association with blistering on his right leg. He had peripheral blood eosinophilia ranging from 0.91 to 1.17×109/L with no biochemical evidence of sepsis. Skin biopsy revealed dermal interstitial lymphocytic infiltration with numerous eosinophils at various stages of degranulation, along with flame figures. EC causing pseudo-cellulitis was suspected. Three fecal samples were unyielding for ova and cysts, but Strongyloides immunoglobulin G serology was positive. The diagnosis of EC secondary to occult strongyloidiasis was made and the patient was treated with oral anti-helminthics and topical steroids with all the skin lesions resolving within 4 days. To our knowledge, this association has never been hitherto reported. This case showcases the following instructive points to the internist, namely (I) the low threshold to consider pseudo-cellulitis in apparent “bilateral lower limb cellulitis”; (II) the awareness of the entity of EC and the need to evaluate for underlying etiologies that cause this reactive dermatoses, such as including occult helminthic infections; (III) the correct way to perform a thorough evaluation for, and optimal treatment of helminthiasis. -

61% of All Human Pathogens Are Zoonotic (Passed from Animals to Humans), and Many Are Transmitted Through Inhaling Dust Particles Or Contact with Animal Wastes

Zoonotic Diseases Fast Facts: 61% of all human pathogens are zoonotic (passed from animals to humans), and many are transmitted through inhaling dust particles or contact with animal wastes. Some of the diseases we can get from our pets may be fatal if they go undetected or undiagnosed. All are serious threats to human health, but can usually be avoided by observing a few precautions, the most effective of which is washing your hands after touching animals or their wastes. Regular visits to the veterinarian for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of zoonotic diseases will help limit disease in your pet. Source: http://www.cdc.gov/healthypets/ Some common zoonotic diseases humans can get through their pets: Zoonotic Disease & its Effect on How Contact is Made Humans Bartonellosis (cat scratch disease) – an Bartonella bacteria are transferred to humans through infection from the bacteria Bartonella a bite or scratch. Do not play with stray cats, and henselae that causes fever and swollen keep your cat free of fleas. Always wash hands after lymph nodes. handling your cat. Capnocytophaga infection – an Capnocytophaga canimorsus is the main human infection caused by bacteria that can pathogen associated with being licked or bitten by an develop into septicemia, meningitis, infected dog and may present a problem for those and endocarditis. who are immunosuppressed. Cellulitis – a disease occurring when Bacterial organisms from the Pasteurella species live bacteria such as Pasteurella multocida in the mouths of most cats, as well as a significant cause a potentially serious infection of number of dogs and other animals. These bacteria the skin. -

Identifying Co-Endemic Areas for Major Filarial Infections in Sub-Saharan

Cano et al. Parasites & Vectors (2018) 11:70 DOI 10.1186/s13071-018-2655-5 SHORTREPORT Open Access Identifying co-endemic areas for major filarial infections in sub-Saharan Africa: seeking synergies and preventing severe adverse events during mass drug administration campaigns Jorge Cano1* , Maria-Gloria Basáñez2, Simon J. O’Hanlon2, Afework H. Tekle4, Samuel Wanji3,4, Honorat G. Zouré5, Maria P. Rebollo6 and Rachel L. Pullan1 Abstract Background: Onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis (LF) are major filarial infections targeted for elimination in most endemic sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries by 2020/2025. The current control strategies are built upon community-directed mass administration of ivermectin (CDTI) for onchocerciasis, and ivermectin plus albendazole for LF, with evidence pointing towards the potential for novel drug regimens. When distributing microfilaricides however, considerable care is needed to minimise the risk of severe adverse events (SAEs) in areas that are co-endemic for onchocerciasis or LF and loiasis. This work aims to combine previously published predictive risk maps for onchocerciasis, LF and loiasis to (i) explore the scale of spatial heterogeneity in co-distributions, (ii) delineate target populations for different treatment strategies, and (iii) quantify populations at risk of SAEs across the continent. Methods: Geographical co-endemicity of filarial infections prior to the implementation of large-scale mass treatment interventions was analysed by combining a contemporary LF endemicity map with predictive prevalence maps of onchocerciasis and loiasis. Potential treatment strategies were geographically delineated according to the level of co-endemicity and estimated transmission intensity. Results: In total, an estimated 251 million people live in areas of LF and/or onchocerciasis transmission in SSA, based on 2015 population estimates.