A New Perspective on Antisthenes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Cynicism

A HISTORY OF CYNICISM Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com A HISTORY OF CYNICISM From Diogenes to the 6th Century A.D. by DONALD R. DUDLEY F,llow of St. John's College, Cambrid1e Htmy Fellow at Yale University firl mll METHUEN & CO. LTD. LONDON 36 Essex Street, Strand, W.C.2 Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com First published in 1937 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com PREFACE THE research of which this book is the outcome was mainly carried out at St. John's College, Cambridge, Yale University, and Edinburgh University. In the help so generously given to my work I have been no less fortunate than in the scenes in which it was pursued. I am much indebted for criticism and advice to Professor M. Rostovtseff and Professor E. R. Goodonough of Yale, to Professor A. E. Taylor of Edinburgh, to Professor F. M. Cornford of Cambridge, to Professor J. L. Stocks of Liverpool, and to Dr. W. H. Semple of Reading. I should also like to thank the electors of the Henry Fund for enabling me to visit the United States, and the College Council of St. John's for electing me to a Research Fellowship. Finally, to• the unfailing interest, advice and encouragement of Mr. M. P. Charlesworth of St. John's I owe an especial debt which I can hardly hope to repay. These acknowledgements do not exhaust the list of my obligations ; but I hope that other kindnesses have been acknowledged either in the text or privately. -

Epicurus and the Epicureans on Socrates and the Socratics

chapter 8 Epicurus and the Epicureans on Socrates and the Socratics F. Javier Campos-Daroca 1 Socrates vs. Epicurus: Ancients and Moderns According to an ancient genre of philosophical historiography, Epicurus and Socrates belonged to distinct traditions or “successions” (diadochai) of philosophers. Diogenes Laertius schematizes this arrangement in the following way: Socrates is placed in the middle of the Ionian tradition, which starts with Thales and Anaximander and subsequently branches out into different schools of thought. The “Italian succession” initiated by Pherecydes and Pythagoras comes to an end with Epicurus.1 Modern views, on the other hand, stress the contrast between Socrates and Epicurus as one between two opposing “ideal types” of philosopher, especially in their ways of teaching and claims about the good life.2 Both ancients and moderns appear to agree on the convenience of keeping Socrates and Epicurus apart, this difference being considered a fundamental lineament of ancient philosophy. As for the ancients, however, we know that other arrangements of philosophical traditions, ones that allowed certain connections between Epicureanism and Socratism, circulated in Hellenistic times.3 Modern outlooks on the issue are also becoming more nuanced. 1 DL 1.13 (Dorandi 2013). An overview of ancient genres of philosophical history can be seen in Mansfeld 1999, 16–25. On Diogenes’ scheme of successions and other late antique versions of it, see Kienle 1961, 3–39. 2 According to Riley 1980, 56, “there was a fundamental difference of opinion concerning the role of the philosopher and his behavior towards his students.” In Riley’s view, “Epicurean criticism was concerned mainly with philosophical style,” not with doctrines (which would explain why Plato was not as heavily attacked as Socrates). -

Thales of Miletus Sources and Interpretations Miletli Thales Kaynaklar Ve Yorumlar

Thales of Miletus Sources and Interpretations Miletli Thales Kaynaklar ve Yorumlar David Pierce October , Matematics Department Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Istanbul http://mat.msgsu.edu.tr/~dpierce/ Preface Here are notes of what I have been able to find or figure out about Thales of Miletus. They may be useful for anybody interested in Thales. They are not an essay, though they may lead to one. I focus mainly on the ancient sources that we have, and on the mathematics of Thales. I began this work in preparation to give one of several - minute talks at the Thales Meeting (Thales Buluşması) at the ruins of Miletus, now Milet, September , . The talks were in Turkish; the audience were from the general popu- lation. I chose for my title “Thales as the originator of the concept of proof” (Kanıt kavramının öncüsü olarak Thales). An English draft is in an appendix. The Thales Meeting was arranged by the Tourism Research Society (Turizm Araştırmaları Derneği, TURAD) and the office of the mayor of Didim. Part of Aydın province, the district of Didim encompasses the ancient cities of Priene and Miletus, along with the temple of Didyma. The temple was linked to Miletus, and Herodotus refers to it under the name of the family of priests, the Branchidae. I first visited Priene, Didyma, and Miletus in , when teaching at the Nesin Mathematics Village in Şirince, Selçuk, İzmir. The district of Selçuk contains also the ruins of Eph- esus, home town of Heraclitus. In , I drafted my Miletus talk in the Math Village. Since then, I have edited and added to these notes. -

Heraclitus on Pythagoras

Leonid Zhmud Heraclitus on Pythagoras By the time of Heraclitus, criticism of one’s predecessors and contemporaries had long been an established literary tradition. It had been successfully prac ticed since Hesiod by many poets and prose writers.1 No one, however, practiced criticism in the form of persistent and methodical attacks on both previous and current intellectual traditions as effectively as Heraclitus. Indeed, his biting criti cism was a part of his philosophical method and, on an even deeper level, of his selfappraisal and selfunderstanding, since he alone pretended to know the correct way to understand the underlying reality, unattainable even for the wisest men of Greece. Of all the celebrities figuring in Heraclitus’ fragments only Bias, one of the Seven Sages, is mentioned approvingly (DK 22 B 39), while another Sage, Thales, is the only one mentioned neutrally, as an astronomer (DK 22 B 38). All the others named by Heraclitus, which is to say the three most famous poets, Homer, Hesiod and Archilochus, the philosophical poet Xenophanes, Pythago ras, widely known for his manifold wisdom, and finally, the historian and geog rapher Hecataeus – are given their share of opprobrium.2 Despite all the intensity of Heraclitus’ attacks on these famous individuals, one cannot say that there was much personal in them. He was not engaged in ordi nary polemics with his contemporaries, as for example Xenophanes, Simonides or Pindar were.3 Xenophanes and Hecataeus, who were alive when his book was written, appear only once in his fragments, and even then only in the company of two more famous people, Hesiod and Pythagoras (DK 22 B 40). -

MINEOLA BIBLE INSTITUTE and SEMINARY Philosophy II Radically

MINEOLA BIBLE INSTITUTE AND SEMINARY Page | 1 Philosophy II Radically, Biblical, Apostolic, Christianity Bishop D.R. Vestal, PhD Larry L Yates, ThD, DMin “Excellence in Apostolic Education since 1991” 1 Copyright © 2019 Mineola Bible Institute Page | 2 All Rights Reserved This lesson material may not be used in any manner for reproduction in any language or use without the written permission of Mineola Bible Institute. 2 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 7 Alexander the Great (356-323 B.C.) ........................................................................................... 8 Philip II of Macedonia (382-336 B.C.) ....................................................................................... 12 Page | 3 “Olympias the mother of Alexander was an evil woman. .......................................... 13 Philip II (of Macedonia) (382-336 BC) .............................................................................. 13 Aristotle (384-322 BC) ............................................................................................................... 15 Works .................................................................................................................................... 16 Methods ............................................................................................................................... 17 Doctrines ............................................................................................................................ -

Early Greek Ethics

Comp. by: SatchitananthaSivam Stage : Proof ChapterID: 0004760437 Date:25/2/20 Time:13:07:47 Filepath:d:/womat-filecopy/0004760437.3D Dictionary : NOAD_USDictionary 3 OUP UNCORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FIRST PROOF, 25/2/2020, SPi Early Greek Ethics Edited by DAVID CONAN WOLFSDORF 1 Comp. by: SatchitananthaSivam Stage : Proof ChapterID: 0004760437 Date:25/2/20 Time:13:07:47 Filepath:d:/womat-filecopy/0004760437.3D Dictionary : NOAD_USDictionary 5 OUP UNCORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FIRST PROOF, 25/2/2020, SPi Table of Contents Abbreviations ix Chapter Abstracts and Contributor Information xiii Introduction xxvii David Conan Wolfsdorf PART I INDIVIDUALS AND TEXTS 1. The Pythagorean Acusmata 3 Johan C. Thom 2. Xenophanes on the Ethics and Epistemology of Arrogance 19 Shaul Tor 3. On the Ethical Dimension of Heraclitus’ Thought 37 Mark A. Johnstone 4. Ethics and Natural Philosophy in Empedocles 54 John Palmer 5. The Ethical Life of a Fragment: Three Readings of Protagoras’ Man Measure Statement 74 Tazuko A. van Berkel 6. The Logos of Ethics in Gorgias’ Palamedes, On What is Not, and Helen 110 Kurt Lampe 7. Responsibility Rationalized: Action and Pollution in Antiphon’s Tetralogies 132 Joel E. Mann 8. Ethical and Political Thought in Antiphon’s Truth and Concord 149 Mauro Bonazzi 9. The Ethical Philosophy of the Historical Socrates 169 David Conan Wolfsdorf 10. Prodicus on the Choice of Heracles, Language, and Religion 195 Richard Bett 11. The Ethical Maxims of Democritus of Abdera 211 Monte Ransome Johnson 12. The Sophrosynē of Critias: Aristocratic Ethics after the Thirty Tyrants 243 Alex Gottesman Comp. by: SatchitananthaSivam Stage : Proof ChapterID: 0004760437 Date:25/2/20 Time:13:07:48 Filepath:d:/womat-filecopy/0004760437.3D Dictionary : NOAD_USDictionary 6 OUP UNCORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FIRST PROOF, 25/2/2020, SPi vi 13. -

The Fragments of Zeno and Cleanthes, but Having an Important

,1(70 THE FRAGMENTS OF ZENO AND CLEANTHES. ftonton: C. J. CLAY AND SONS, CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE, AVE MARIA LANE. ambriDse: DEIGHTON, BELL, AND CO. ltip>ifl: F. A. BROCKHAUS. #tto Hork: MACMILLAX AND CO. THE FRAGMENTS OF ZENO AND CLEANTHES WITH INTRODUCTION AND EXPLANATORY NOTES. AX ESSAY WHICH OBTAINED THE HARE PRIZE IX THE YEAR 1889. BY A. C. PEARSON, M.A. LATE SCHOLAR OF CHRIST S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE. LONDON: C. J. CLAY AND SONS, CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE. 1891 [All Rights reserved.] Cambridge : PBIXTKIi BY C. J. CLAY, M.A. AND SONS, AT THK UNIVERSITY PRKSS. PREFACE. S dissertation is published in accordance with thr conditions attached to the Hare Prize, and appears nearly in its original form. For many reasons, however, I should have desired to subject the work to a more under the searching revision than has been practicable circumstances. Indeed, error is especially difficult t<> avoid in dealing with a large body of scattered authorities, a the majority of which can only be consulted in public- library. to be for The obligations, which require acknowledged of Zeno and the present collection of the fragments former are Cleanthes, are both special and general. The Philo- soon disposed of. In the Neue Jahrbticher fur Wellmann an lofjie for 1878, p. 435 foil., published article on Zeno of Citium, which was the first serious of Zeno from that attempt to discriminate the teaching of Wellmann were of the Stoa in general. The omissions of the supplied and the first complete collection fragments of Cleanthes was made by Wachsmuth in two Gottingen I programs published in 187-i LS75 (Commentationes s et II de Zenone Citiensi et Cleaitt/ie Assio). -

Epicurus on Socrates in Love, According to Maximus of Tyre Ágora

Ágora. Estudos Clássicos em debate ISSN: 0874-5498 [email protected] Universidade de Aveiro Portugal CAMPOS DAROCA, F. JAVIER Nothing to be learnt from Socrates? Epicurus on Socrates in love, according to Maximus of Tyre Ágora. Estudos Clássicos em debate, núm. 18, 2016, pp. 99-119 Universidade de Aveiro Aveiro, Portugal Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=321046070005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Nothing to be learnt from Socrates? Epicurus on Socrates in love, according to Maximus of Tyre Não há nada a aprender com Sócrates? Epicuro e os amores de Sócrates, segundo Máximo de Tiro F. JAVIER CAMPOS DAROCA (University of Almería — Spain) 1 Abstract: In the 32nd Oration “On Pleasure”, by Maximus of Tyre, a defence of hedonism is presented in which Epicurus himself comes out in person to speak in favour of pleasure. In this defence, Socrates’ love affairs are recalled as an instance of virtuous behaviour allied with pleasure. In this paper we will explore this rather strange Epicurean portrayal of Socrates as a positive example. We contend that in order to understand this depiction of Socrates as a virtuous lover, some previous trends in Platonism should be taken into account, chiefly those which kept the relationship with the Hellenistic Academia alive. Special mention is made of Favorinus of Arelate, not as the source of the contents in the oration, but as the author closest to Maximus both for his interest in Socrates and his rhetorical (as well as dialectical) ways in philosophy. -

Thales of Miletus Sources and Interpretations Miletli Thales Kaynaklar Ve Yorumlar

Thales of Miletus Sources and Interpretations Miletli Thales Kaynaklar ve Yorumlar David Pierce September , Matematics Department Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Istanbul http://mat.msgsu.edu.tr/~dpierce/ This is a collection of what I have been able to find or figure out about Thales of Miletus. It may be useful for anybody interested in Thales. I focus directly on the ancient sources that we have. ¶ I began collecting these notes in preparation to give one of several -minute talks at the Thales Meeting (Thales Buluşması) at the ruins of Miletus, now Milet, Septem- ber , . Talks at the meeting were in Turkish; the au- dience, members of the general population. I chose for my title “Thales as the originator of the concept of proof” (Kanıt kavramının öncüsü olarak Thales). ¶ The Thales Meeting was arranged by the office of the mayor of Didim. Part of Aydın province, the district of Didim encompasses the ancient cities of Priene and Miletus, along with the temple of Didyma, which was linked to Miletus. Herodotus refers to Didyma under the name of the family of priests there, the Branchidae. ¶ One can visit all three of Priene, Didyma, and Miletus in a day. I did this in , while teaching at the Nesin Mathematics Village in Şirince, in the district of Selçuk, which contains also the ruins of Ephesus, home town of Heraclitus. My excellent guide was George Bean, Aegean Turkey []. Contents . Sources .. AlegendfromDiogenesLaertius . .. Kirk, Raven, and Schofield . .. DielsandKranz. .. Collingwood. .. .. .. Herodotus ..................... ... Solareclipse . ... CrossingoftheHalys . ... BouleuterionatTeos . .. Proclus....................... ... Originofgeometry . ... Bisectionofcircle . ... Isosceles triangles . ... Verticalangles. ... Congruenttriangles. .. Diogenes Laertius: The angle in a semicircle . -

Could Iamblichus Help Us to Understand One Ancient Relief?

COULD IAMBLICHUS HELP US TO UNDERSTAND ONE ANCIENT RELIEF? ANNA AFONASINA Tomsk State University Novosibirsk State University, Russia [email protected] ABSTRACT . Describing Pythagoras’ activities in Croton Iamblichus summarizes the content of his public speeches addressed to young men, to the Thousand who governed the city, as well as children and women of Croton. The earliest evidences about the Pythagoras’ speeches, available to us are found in an Athenian rhetorician and a pupil of Socrates Antisthenes (450–370 BCE), the historians Dicearchus and Timaeus, and Isocrates. In the present paper I consider the content of the Pythagoras’ speeches, preserved by Iamblichus, in more details, in order to suggest a new interpretation of the famous grave relief from the Antikensammlung, Berlin (Sk 1462). The relief, found in an “Olive grove on the road to Eleusis” and dated to the first century BCE, presents an image of a sitting half-naked bearded man with a young man, also half-naked, standing behind his chair, and a group of peoples consisting of a child, an older man and a woman, standing in front of him. Our attention attracts a big and clear im- age of the letter ‘Psi’ above the scene. The comparison of the content of Pythagoras’ speeches with the scene depicted on the relief allows us to interpret the image as following: we suggest that the sitting man, undoubtedly a philosopher, could be a Pythagorean or Pythagoras him- self; he is attended by his pupil and gives speeches to different groups of peoples, symbolically represented as a young man, a public agent, a woman and a child. -

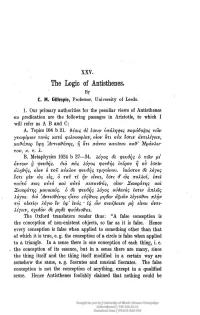

The Logic of Antisthenes. by C* M

XXV. The Logic of Antisthenes. By C* M. Gillespie, Professor, University of Leeds. 1. Our primary authorities for the peculiar views of Antisthenes on predication are the following passages in Aristotle, to which I will refer as A B and C: A. Topics 104 b 21. &έοις όε εοτιν νπόληψις παράόοξος των γνωρίμων τινός κατά φιλοοοφίαν, οίον ότι ονκ εστίν άντιλέγειν, χα&άπερ εφη *Αντιϋ&ένης, η ότι πάντα κινείται êá&' Ηράκλει- το», ê. τ. ë. Â. Metaphysics 1024 b 27—34. λόγος όε ψενόής δ των μ? Όντων ?) ψενόής. όιο πάς λόγος ψενόής έτερον η ον εϋτιν άλη&ής, οίον δ τον κνκλον ψενόής τριγωνον. εκάΰτον όε λόγος %στι μεν ως εις, δ τον τι ην είναι, εΰτι ό' ως πολλοί, έπε é ταντό πως αντό êáé αντό πεπον&ός, οίον Σωκράτης êáé Σωκράτης μονΰικός. δ όε ψενόής λόγος ονόενός εοτιν απλώς λόγος, όιο Άντιο&ένης ωετο ενή&ως μηδέν αξιών λέγεϋ&αι πλην τω οικείω λόγo^ εν Ιφ* ενός ' εξ ων όννέβαινε μη είναι άντι- λέγεη?, Οχεόον όε μηόε ιρενόεΰ&αι. The Oxford translators/render thus: "A false conception is the conception of non-existent objects, so far as it is false. Hence every conception is false when applied to something other than that of which it is true, e. g. the conception of a circle is false when applied to a triangle. In a sense there is one conception of each thing, i. e. the conception of its essence, but in a sense there are many, since the thing itself and the thing itself modified in a certain way are somehow the same, e. -

Chapter One the SAYING of ANTISTHENES the ASKESIS of the EARLY GREEK CYNICS

Chapter One THE SA YING OF ANTISTHENES & THE ASKESIS OF THE EARLY GREEK CYNICS ] 'aitOlgolfrs distinglle, en ejfet, dans Ie diJ"Collrs, Ie di11? et Ie dit. QIIe Ie di11? doive fomporterlin dit est line nefessite dllme me ord11? qlle felle qlli imp ose line societe, avec des lo is, des institlltions et des 11?lations so ciales. iVlaisIe dire, e'est Ie foit que de vant Ie visagei: ne restepas simplement /a a Ie contempler,je Ill i riponds. Ledire est linemaniere de saltier alllmi, mais saltier alltmi, e'est dija ripond11? de Illi. (E. Livinas, Ethiqlle et bifini, Paris: FCfYard, 1982, pp . 92-93) The valrle!essnw" ofItfo (die Werlhlosigkeit des le bms) was grasped by the 0nics, bllt it wasn 'tyet app lied against Itfl . (F.Nie tZJ·,·he, Posth"moIlJ" Fragments Slimmer 1882-Spnng 1884, 7[222J) Introduction In this part of the dissertation, I will be considering the early Greek Cynics, and particularly Antisthenes and Diogenes of Sinope. I will analyzeAntisthenes' ethics and theory of language before studying the ethics of the early Greek Cynics.l Rather than distinguishing between Antisthenes' ethics and theory oflanguage as most earlier scholars have done, I will try to show how his theory oflanguage 1 Our main primarysou rce fo r Antisthenes and the early Greek Cynics is Diogenes Laertius. The SL...:th book of his Lives and Opinions oj-Eminent Philosophersis dedicated to the early Cynics. There are also various references in Aristotle, Stobaeus, Plutarch, the Gnom% giJ{m Vati,"tlnllm, Philodemus, Clement of Alexandria, Sirnplicius,Julian, and Epictetus, just to cite a fe "T.