Gastrointestinal Cancer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flexible Sigmoidoscopy in Asymptomatic Patients with Negative Fecal Occult Blood Tests Joy Garrison Cauffman, Phd, Jimmy H

Flexible Sigmoidoscopy in Asymptomatic Patients with Negative Fecal Occult Blood Tests Joy Garrison Cauffman, PhD, Jimmy H. Hara, MD, Irving M. Rasgon, MD, and Virginia A. Clark, PhD Los Angeles, California Background. Although the American Cancer Society and tients with lesions were referred for colonoscopy; addi others haw established guidelines for colorectal cancer tional lesions were found in 14%. A total of 62 lesions screening, questions of who and how to screen still exist. were discovered, including tubular adenomas, villous Methods. A 60-crn flexible sigmoidoscopy was per adenomas, tubular villous adenomas (23 of the adeno formed on 1000 asymptomatic patients, 45 years of mas with atypia), and one adenocarcinoma. The high age or older, with negative fecal occult blood tests, est percentage of lesions discovered were in the sig who presented for routine physical examinations. Pa moid colon and the second highest percentage were in tients with clinically significant lesions were referred for the ascending colon. colonoscopy. The proportion of lesions that would not Conclusions. The 60-cm flexible sigmoidoscope was have been found if the 24-cm rigid or the 30-cm flexi able to detect more lesions than either the 24-cm or ble sigmoidoscope had been used was identified. 30-cm sigmoidoscope when used in asymptomatic pa Results. Using the 60-cm flexible sigmoidoscope, le tients, 45 years of age and over, with negative fecal oc sions were found in 3.6% of the patients. Eighty per cult blood tests. When significant lesions are discovered cent of the significant lesions were beyond the reach of by sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy should be performed. -

What Is a Rigid Sigmoidoscopy?

Learning about . Rigid Sigmoidoscopy What is a rigid sigmoidoscopy? Rigid sigmoidoscopy is a procedure done to look at the rectum and lower colon. The doctor uses a special tube called a scope. The scope has a light and a small glass window at the end so the doctor can see inside. lower colon rectum anus or opening to rectum This procedure is done for many reasons. Some reasons are: • to look for the cause of rectal bleeding • a tissue sample to test called a biopsy When small growths of tissue called polyps are seen, these are removed. The procedure takes about 5 minutes but plan to be at the hospital for ½ hour. Are there any complications to this procedure? Your doctor will explain the problems that can occur before you sign a consent form. Problems are rare but include: The scope can damage the lining of the colon. The scope can cause severe bleeding by damaging the wall of the colon. You may have blood spotting if a biopsy is done or a polyp is removed. Since the doctor and nurse are with you all of the time, they can manage any problem that may occur. What do I need to do to get ready at home? 4 to 5 days before your procedure: Taking medications: Your doctor may want you to stop taking certain medications 4 to 5 days before the procedure. If you need to stop any medications, your doctor will tell you during the office visit. If you have any questions, call the doctor’s office. Buying a Fleet enema: Your bowel must be clean and empty of waste material before this procedure. -

04. EDITORIAL 1/2/06 10:34 Página 853

04. EDITORIAL 1/2/06 10:34 Página 853 1130-0108/2005/97/12/853-859 REVISTA ESPAÑOLA DE ENFERMEDADES DIGESTIVAS REV ESP ENFERM DIG (Madrid) Copyright © 2005 ARÁN EDICIONES, S. L. Vol. 97, N.° 12, pp. 853-859, 2005 Cost-effectiveness of abdominal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of colorectal carcinoma Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a most common neoplasm, and the second leading cause of cancer-related death. CRC was responsible for 11% of cancer-related deaths in males, and for 15% of cancer-related deaths in females according to data for year 2000. Most recent data reported in Spain on death causes in 2002 suggest that CRC was responsible for 12,183 deaths (6,896 males with a mean age of 70 years, and 5,287 women with a mean age of 71 years). In these tumors, mortality data do not reflect the true incidence of this disease, since survival has improved in recent years, particularly in younger individuals. In contrast to other European countries, Spain ranks in an intermediate position in terms of CRC-re- lated incidence and mortality. This risk clearly increases with age, with a notori- ous rise in incidence from 50 years of age on. Survival following CRC detection and management greatly depends upon tumor stage at the time of diagnosis; hence the importance of early detection and –because of their malignant poten- tial– of the recognition and excision of colorectal adenomas. Thus, polypectomy and then surveillance are the primary cornerstones in the prevention of CRC (1-4). For primary prevention, fiber-rich diets, physical exercising, and the avoidance of overweight, smoking, and alcohol have been recommended. -

Flexible Sigmoidoscopy with Haemorrhoid Banding

Flexible sigmoidoscopy with haemorrhoid banding You have been referred by your doctor to have a flexible sigmoidoscopy which may also include haemorrhoid banding. If you are unable to keep your appointment, please notify the department as soon as possible. This will allow staff to give your appointment to someone else and they will arrange another date and time for you. This booklet has been written to explain the procedures. This will help you make an informed decision in relation to consenting to the investigation. Please read the booklets and consent form carefully. You will need to complete the enclosed questionnaire. You may be contacted via telephone by a trained endoscopy nurse before the procedure, to go through the admission process and answer any queries you may have. If you are not contacted please come to your appointment at the time stated on your letter. If you have any mobility problems or there is a possibility you could be pregnant please telephone appointments staff on 01284 712748. Please note the appointment time is your arrival time on the unit, and not the time of your procedure. Please remember there will be other patients in the unit who arrive after you, but are taken in for their procedure before you. This is either for medical reasons or they are seeing a different Doctor. Due to the limited space available and to maintain other patients’ privacy and dignity, we only allow patients (and carers) through to the ward area. Relatives/escorts will be contacted once the person is available for collection. The Endoscopy Unit endeavours to offer single sex facilities, and we aim to make your stay as comfortable and stress free as possible. -

Flexible Sigmoidoscopy – Outpatients

Flexible sigmoidoscopy – Outpatients You have been referred by your doctor to have a flexible sigmoidoscopy. his information booklet has been written to explain the procedure. This will help you to make an informed decision before consenting to the procedure. If you are unable to attend your appointment please inform us as soon as possible. Please ensure you read this booklet and the enclosed consent form thoroughly. Please also complete the enclosed health questionnaire. You may be contacted by an endoscopy trained nurse before your procedure to go through the admission process and answer any queries you may have. If you are not contacted please come to your appointment at the time stated in your letter. Please note your appointment time is your arrival time on the unit and not the time of your procedure. If you have any mobility issues or if there is a possibility you could be pregnant, please contact the appointment staff on 01284 713551 Please remember there will be other patients in the unit who may arrive after you but are taken in for their procedure before you, this is for medical reasons or they are seeing a different doctor. Due to limited space available and to maintain other patients’ privacy and dignity, we only allow patients (and carers) through to the ward area. Relatives/ escorts will be contacted once you are ready for collection. The Endoscopy Unit endeavours to offer single sex facilities, and we aim to make you stay as comfortable and stress free as possible. Source: Endoscopy Reference No: 5035-14 Issue date: 8/1/21 Review date: 8/1/24 Page 1 of 11 Medication If you are taking WARFARIN, CLOPIDOGREL, RIVAROXABAN or any other anticoagulant (blood thinning medication), please contact the appointment staff on 01284 713551, your GP or anticoagulation nurse, as special arrangements may be necessary. -

Anesthesiology Services for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Reference Number: CP.MP.161 Coding Implications Last Review Date: 05/19 Revision Log

Clinical Policy: Anesthesiology Services for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Reference Number: CP.MP.161 Coding Implications Last Review Date: 05/19 Revision Log See Important Reminder at the end of this policy for important regulatory and legal information. Description Conscious sedation for gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopic procedures is standard of care to relieve patient anxiety and discomfort, improve outcomes of the examination, and decrease the memory of the procedure. A combination of an opioid and benzodiazepine is the recommended regimen for achieving minimal to moderate sedation for upper endoscopy and colonoscopy in people without risk for sedation-related adverse events.5 Generally, the gastroenterologist performing the procedure and/or his/her qualified assistant can adequately manage the administration of conscious sedation and monitoring of the patient. In cases with sedation-related risk factors, additional assistance from an anesthesia team member is required to ensure the safest outcome for the patient. This policy outlines the indications for which anesthesia services are considered medically necessary. Policy/Criteria I. It is the policy of health plans affiliated with Centene Corporation® that anesthesiology services for GI endoscopic procedures is considered medically necessary for the following indications: A. Age < 18 years or ≥ 70 years; B. Pregnancy; C. Increased risk of complications due to physiological status as identified by the American Society of Anesthesiologist (ASA) physical status classification of ASA III or higher; D. Increased risk for airway obstruction because of anatomic variants such as dysmorphic facial features, oral abnormalities, neck abnormalities, or jaw abnormalities; E. History of or anticipated intolerance to conscious sedation (i.e. chronic opioid or benzodiazepine use); F. -

Icd-9-Cm (2010)

ICD-9-CM (2010) PROCEDURE CODE LONG DESCRIPTION SHORT DESCRIPTION 0001 Therapeutic ultrasound of vessels of head and neck Ther ult head & neck ves 0002 Therapeutic ultrasound of heart Ther ultrasound of heart 0003 Therapeutic ultrasound of peripheral vascular vessels Ther ult peripheral ves 0009 Other therapeutic ultrasound Other therapeutic ultsnd 0010 Implantation of chemotherapeutic agent Implant chemothera agent 0011 Infusion of drotrecogin alfa (activated) Infus drotrecogin alfa 0012 Administration of inhaled nitric oxide Adm inhal nitric oxide 0013 Injection or infusion of nesiritide Inject/infus nesiritide 0014 Injection or infusion of oxazolidinone class of antibiotics Injection oxazolidinone 0015 High-dose infusion interleukin-2 [IL-2] High-dose infusion IL-2 0016 Pressurized treatment of venous bypass graft [conduit] with pharmaceutical substance Pressurized treat graft 0017 Infusion of vasopressor agent Infusion of vasopressor 0018 Infusion of immunosuppressive antibody therapy Infus immunosup antibody 0019 Disruption of blood brain barrier via infusion [BBBD] BBBD via infusion 0021 Intravascular imaging of extracranial cerebral vessels IVUS extracran cereb ves 0022 Intravascular imaging of intrathoracic vessels IVUS intrathoracic ves 0023 Intravascular imaging of peripheral vessels IVUS peripheral vessels 0024 Intravascular imaging of coronary vessels IVUS coronary vessels 0025 Intravascular imaging of renal vessels IVUS renal vessels 0028 Intravascular imaging, other specified vessel(s) Intravascul imaging NEC 0029 Intravascular -

2020 GI Endoscopy Coding and Reimbursement Guide

2020 GI Endoscopy Coding and Reimbursement Guide Disclaimer: The information provided herein reflects Cook’s understanding of the procedure(s) and/or device(s) from sources that may include, but are not limited to, the CPT® coding system; Medicare payment systems; commercially available coding guides; professional societies; and research conducted by independent coding and reimbursement consultants. This information should not be construed as authoritative. The entity billing Medicare and/or third party payers is solely responsible for the accuracy of the codes assigned to the services and items in the medical record. Cook does not, and should not, have access to medical records, and therefore cannot recommend codes for specific cases. When you are making coding decisions, we encourage you to seek input from the AMA, relevant medical societies, CMS, your local Medicare Administrative Contractor and other health plans to which you submit claims. Cook does not promote the off-label use of its devices. The reimbursement rates provided are national Medicare averages published by CMS at the time this guide was created. Reimbursement rates may change due to addendum updates Medicare publishes throughout the year and may not be reflected on the guide. CPT © 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. CPT is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association. If you have any questions, please contact our reimbursement team at 800.468.1379 or by e-mail at [email protected]. 2020 GI Endoscopy Guide Medicare Reimbursement -

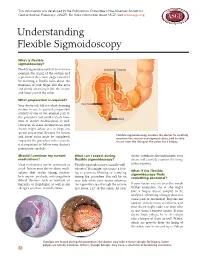

Understanding Flexible Sigmoidoscopy

This information was developed by the Publications Committee of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE). For more information about ASGE, visit www.asge.org. Understanding Flexible Sigmoidoscopy What is flexible sigmoidoscopy? Flexible sigmoidoscopy lets your doctor SIGMOID COLON examine the lining of the rectum and a portion of the colon (large intestine) by inserting a flexible tube about the thickness of your finger into the anus and slowly advancing it into the rectum and lower part of the colon. What preparation is required? Your doctor will tell you what cleansing RECTUM routine to use. In general, preparation consists of one or two enemas prior to the procedure but could include laxa- ANUS tives or dietary modifications as well. However, in some circumstances your doctor might advise you to forgo any special preparation. Because the rectum Flexible sigmoidoscopy enables the doctor to carefully and lower colon must be completely examine the rectum and sigmoid colon, and to take empty for the procedure to be accurate, tissue from the lining of the colon for a biopsy. it is important to follow your doctor’s instructions carefully. Should I continue my current What can I expect during doctor withdraws the instrument, your medications? flexible sigmoidoscopy? doctor will carefully examine the lining Most medications can be continued as Flexible sigmoidoscopy is usually well- of the intestine. usual. Inform your doctor about medi- tolerated. You might experience a feel- What if the flexible cations that you’re taking, particu- ing of pressure, bloating or cramping sigmoidoscopy finds larly aspirin products, anti-coagulants during the procedure. -

Are Proximal Colorectal Cancers Always Associated with Distal

COMMENTARIES 317 Colon cancer sigmoidoscope. This additional examina- ................................................................................... tion above that of conventional flexible sigmoidoscopy resulted in a further 3% of patients being offered full colonoscopy Are proximal colorectal cancers and three proximal carcinomas being Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.52.3.318 on 1 March 2003. Downloaded from detected in subjects who would have always associated with distal otherwise been misclassified as having no neoplasia. The authors conclude that adenomas? the finding of any adenoma at flexible sigmoidoscopy should trigger a full A J M Watson colonoscopy. They recommend that the initial examination should be an unsed- ................................................................................... ated examination with a colonoscope Only half of proximal colon cancers are associated with adenomas after a simple enema. This study is consistent with previous in the distal colon. This has important implications for the selection findings that 46–52% of PAN are not of the initial investigation for colorectal cancer screening accompanied by distal polyps.10 11 Addi- tion of faecal occult blood testing to flex- f all the common cancers, colo- association of distal adenomas with proxi- ible sigmoidoscopy does not significantly rectal cancer is the best suited to mal colorectal neoplasia [see page 398]. increase the detection of advanced Oprevention through screening as The investigators took advantage of the neoplasia.12 One is therefore left with the it is derived from benign adenomas Norwegian Colorectal Cancer Prevention conclusion that colonoscopy remains the which can be easily detected and re- study (NORCCAP) in which 20 780 indi- most sensitive screening tool and, if per- moved. The best screening investigation viduals aged 54–64 years, selected randomly formed by a skilled operator, is reason- remains much debated. -

About Your Flexible Sigmoidoscopy

PATIENT & CAREGIVER EDUCATION About Your Flexible Sigmoidoscopy This information will help you get ready for your flexible sigmoidoscopy (sig-MOY-DOS-koh-pee). A flexible sigmoidoscopy is an exam of your rectum and lower colon. During your flexible sigmoidoscopy, your healthcare provider will use a flexible tube called an endoscope to see the inside of your rectum and lower colon on a video screen. Your healthcare provider can take a small sample of tissue (do a biopsy) or remove a polyp (growth of tissue) during your procedure. 1 Week Before Your Procedure Ask about your medications You may need to stop taking some of your medications before your procedure. Talk with your healthcare provider about which medications are safe for you to stop taking. We have included some common examples below. Anticoagulants (blood thinners) If you take a blood thinner, such as to treat blood clots or to prevent a heart attack or stroke, ask the doctor who prescribes it for you when to stop taking it. See below for examples of common blood thinners. Blood thinners If you take a blood thinner (medication that affects the way your blood clots), ask the healthcare provider performing your procedure what to do. Whether they recommend you stop taking the medication depends on the type of procedure you’re having and the reason you’re taking blood thinners. Examples of Blood Thinners dalteparin apixaban (Eliquis®) meloxicam (Mobic®) ticagrelor (Brilinta®) (Fragmin®) nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs dipyridamole aspirin (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen (Advil®, -

Sigmoidoscopy: What You Should Know

Sigmoidoscopy: What You Should Know Before this test, you use a strong laxative and/or enema to clean out the colon. Flexible sigmoidoscopy is conducted at the doctor’s office, clinic, or hospital. The doctor uses a narrow, flexible, lighted tube to look at the inside of the rectum and the lower portion of the colon. During the exam, the doctor may remove some polyps (abnormal growths) and collect samples or tissue or cells for more testing. This test is recommended every 5 years. If polyps are found, guidelines indicate that a follow up colonoscopy is recommended. When used together, FOBT is recommended yearly and a flexible sigmoidoscopy is recommended every 5 years. Sigmoidoscopy is the visual examination of the inside of the distal colon, using a lighted, flexible tube connected to an eyepiece or video screen for viewing. This device is called an endoscope. The colon (large intestine) is 5 to 6 feet long. During a sigmoidoscopy, only the last 1 to 2 feet of the colon is examined. This last part of the colon, just above the rectum, is called the sigmoid colon. Why the test is performed? Sigmoidoscopy is performed to diagnose the cause of certain symptoms. It is also used as a preventative measure to detect problems at an early stage, even before the patient recognizes symptoms. The following are some reasons for performing a sigmoidoscopy. Bleeding -- Rectal bleeding is very common. It often is caused by hemorrhoids or by a small tear at the anus, called a fissure. However, more serious problems can cause bleeding.