Textile Fibres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

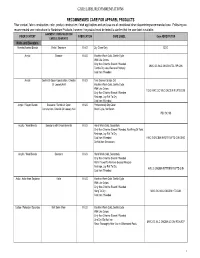

Care Label Recommendations

CARE LABEL RECOMMENDATIONS RECOMMENDED CARE FOR APPAREL PRODUCTS Fiber content, fabric construction, color, product construction, finish applications and end use are all considered when determining recommended care. Following are recommended care instructions for Nordstrom Products, however; the product must be tested to confirm that the care label is suitable. GARMENT/ CONSTRUCTION/ FIBER CONTENT FABRICATION CARE LABEL Care ABREVIATION EMBELLISHMENTS Knits and Sweaters Acetate/Acetate Blends Knits / Sweaters K & S Dry Clean Only DCO Acrylic Sweater K & S Machine Wash Cold, Gentle Cycle With Like Colors Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed MWC GC WLC ONCBIN TDL RP CIIN Tumble Dry Low, Remove Promptly Cool Iron If Needed Acrylic Gentle Or Open Construction, Chenille K & S Turn Garment Inside Out Or Loosely Knit Machine Wash Cold, Gentle Cycle With Like Colors TGIO MWC GC WLC ONCBIN R LFTD CIIN Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry Cool Iron If Needed Acrylic / Rayon Blends Sweaters / Gentle Or Open K & S Professionally Dry Clean Construction, Chenille Or Loosely Knit Short Cycle, No Steam PDC SC NS Acrylic / Wool Blends Sweaters with Embelishments K & S Hand Wash Cold, Separately Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed, No Wring Or Twist Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry Cool Iron If Needed HWC S ONCBIN NWOT R LFTD CIIN DNID Do Not Iron Decoration Acrylic / Wool Blends Sweaters K & S Hand Wash Cold, Separately Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed Roll In Towel To Remove Excess Moisture Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry HWC S ONCBIN RITTREM -

Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout

English by Alain Stout For the Textile Industry Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout Compiled and created by: Alain Stout in 2015 Official E-Book: 10-3-3016 Website: www.TakodaBrand.com Social Media: @TakodaBrand Location: Rotterdam, Holland Sources: www.wikipedia.com www.sensiseeds.nl Translated by: Microsoft Translator via http://www.bing.com/translator Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout Table of Contents For Word .............................................................................................................................. 5 Textile in General ................................................................................................................. 7 Manufacture ....................................................................................................................... 8 History ................................................................................................................................ 9 Raw materials .................................................................................................................... 9 Techniques ......................................................................................................................... 9 Applications ...................................................................................................................... 10 Textile trade in Netherlands and Belgium .................................................................... 11 Textile industry ................................................................................................................... -

Choosing the Proper Short Cut Fiber for Your Nonwoven Web

Choosing The Proper Short Cut Fiber for Your Nonwoven Web ABSTRACT You have decided that your web needs a synthetic fiber. There are three important factors that have to be considered: generic type, diameter, and length. In order to make the right choice, it is important to know the chemical and physical characteristics of the numerous man-made fibers, and to understand what is meant by terms such as denier and denier per filament (dpf). PROPERTIES Denier Denier is a property that varies depending on the fiber type. It is defined as the weight in grams of 9,000 meters of fiber. The current standard of denier is 0.05 grams per 450 meters. Yarn is usually made up of numerous filaments. The denier of the yarn divided by its number of filaments is the denier per filament (dpf). Thus, denier per filament is a method of expressing the diameter of a fiber. Obviously, the smaller the denier per filament, the more filaments there are in the yarn. If a fairly closed, tight web is desired, then lower dpf fibers (1.5 or 3.0) are preferred. On the other hand, if high porosity is desired in the web, a larger dpf fiber - perhaps 6.0 or 12.0 - should be chosen. Here are the formulas for converting denier into microns, mils, or decitex: Diameter in microns = 11.89 x (denier / density in grams per milliliter)½ Diameter in mils = diameter in microns x .03937 Decitex = denier x 1.1 The following chart may be helpful. Our stock fibers are listed along with their density and the diameter in denier, micron, mils, and decitex for each: Diameter Generic Type -

Investigation of the Mechanical Properties of a Carbon Fibre-Reinforced Nylon Filament for 3D Printing

machines Article Investigation of the Mechanical Properties of a Carbon Fibre-Reinforced Nylon Filament for 3D Printing Flaviana Calignano 1,* , Massimo Lorusso 2 , Ignanio Roppolo 3 and Paolo Minetola 1 1 Department of Management and Production Engineering, Politecnico di Torino, Corso Duca degli Abruzzi 24, 10129 Turin, Italy; [email protected] 2 Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Center for Sustainable Future Technologies IIT@Polito, Corso Trento 21, 10129 Turin, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Applied Science and Technology, Politecnico di Torino, Corso Duca degli Abruzzi 24, 10129 Turin, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: fl[email protected]; Tel.: +39-011-090-7218 Received: 19 July 2020; Accepted: 2 September 2020; Published: 4 September 2020 Abstract: Additive manufacturing (i.e., 3D printing) has rapidly developed in recent years. In the recent past, many researchers have highlighted the development of in-house filaments for fused filament fabrication (FFF), which can extend the corresponding field of application. Due to the limited mechanical properties and deficient functionality of printed polymer parts, there is a need to develop printable polymer composites that exhibit high performance. This study analyses the actual mechanical characteristics of parts fabricated with a low-cost printer from a carbon fibre-reinforced nylon filament. The results show that the obtained values differ considerably from the values presented in the datasheets of various filament suppliers. Moreover, the hardness and tensile strength are influenced by the building direction, the infill percentage, and the thermal stresses, whereas the resilience is affected only by the building direction. Furthermore, the relationship between the mechanical properties and the filling factor is not linear. -

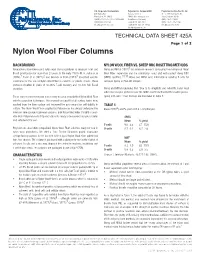

Nylon Wool Fiber Columns

U.S. Corporate Headquarters Polysciences Europe GmbH Polysciences Asia-Pacific, Inc. 400 Valley Rd. Badener Str. 13 2F-1, 207 DunHua N. Rd. Warrington, PA 18976 69493 Hirschberg an der Taipei, Taiwan 10595 1(800) 523-2575 / (215) 343-6484 Bergstrasse, Germany (886) 2 8712 0600 1(800)343-3291 fax +(49) 6201 845 20 0 (886) 2 8712 2677 fax [email protected] +(49) 6201 845 20 20 fax [email protected] [email protected] TECHNICAL DATA SHEET 425A Page 1 of 2 Nylon Wool Fiber Columns BACKGROUND NYLON WOOL FIBER VS. SHEEP RBC ROSETTING METHODS Researchers have been using nylon wool fiber procedures to separate T-cell and Wong and Mittal (1981)9 did extensive research comparing the methods of Nylon B-cell lymphocytes for more than 20 years. In the early 1970’s M. H. Julius et al Wool Fiber separation and the commonly- used and well-studied sheep RBC (1973),1 Eisen et al (1972),2 and Greaves & Brain (1974)3 described specific (SRBC) rosetting.10,11 Wong and Mittal were interested in isolating B-cells for conditions for the use of Nylon Wool Fiber in columns or plastic straws. These serologic typing of HLA-DR antigen. protocols resulted in yields of 50-90% T-cell recovery and 10-100 fold B-cell depletion. Wong and Mittal concluded that “Due to its simplicity and reliability, nylon wool adherence may be preferred over the SRBC rosette method for the routine pheno- These early researchers found it necessary to scrub or wash their Nylon Wool Fiber typing of B-cells.” Their findings are illustrated in Table 1. -

Re:Mix –Separation and Recycling of Textile Waste Fiber Blends

Re:Mix –Separation and recycling of textile waste fiber blends by Åsa Östlund, Per-Olof Syrén, Christina Jönsson, Doris Ribitsch and Marie Syrén report funded by: Titel: Re:Mix - Separation and recycling of textile A Mistra Future Fashion Report waste fiber blends Mistra Future Fashion is a cross-disciplinary Authors: Åsa Östlund1,Per-Olof Syrén2, Christina research program, initiated and primarily fun- Jönsson3, Doris Ribitsch4 and Marie Syrén1 ded by Mistra. It holds a total budget of SEK 110 Affiliations: 1) RISE Research Institutes of Sweden, millions and stretches over 8 years, from 2011 2) KTH/SciLifeLab, 3) BOKU, 4) Swerea IVF to 2019. It is hosted by RISE in collaboration with 13 research partners, and involves more Edition: Only available as PDF for individual printing than 40 industry partners. ISBN: 978-91-88695-06-2 Mistra Future Fashion report number: 2017:6 www.mistrafuturefashion.com Task deliverable MFF phase 2: D.SRF.4.1.1 RE:Source Project No.: 42520-1 © Åsa Östlund, Per-Olof Syrén, Christina Jönsson, Doris Ribitsch, Marie Syrén RISE Research Institutes of Sweden Box 857, 501 15 Borås www.ri.se Images: Swerea IVF, Pixabay Layout: Charlotte Neckmar 1 Table of contents Introductory remark.................................................. 2 Table of contents...................................................... 3 Sammanfattning...................................................... 4 Summary................................................................ 5 1 Introduction and Background................................... 7 Introductory remark 1.1 Scope......................................................... 8 2 Execution of work.................................................. 8 This project ‘Re:Mix - Separation and recycling of textile waste fibre blends’, refer- 2.1 Project constellation and actors..................... 9 red to as Re:Mix I, was a pre-study and thereby included a start-up and consorti- 2.1.1 Management.................................. -

India's Textile and Apparel Industry

Staff Research Study 27 Office of Industries U.S. International Trade Commission India’s Textile and Apparel Industry: Growth Potential and Trade and Investment Opportunities March 2001 Publication 3401 The views expressed in this staff study are those of the Office of Industries, U.S. International Trade Commission. They are not necessarily the views of the U.S. International Trade Commission as a whole or any individual commissioner. U.S. International Trade Commission Vern Simpson Director, Office of Industries This report was principally prepared by Sundar A. Shetty Textiles and Apparel Branch Energy, Chemicals, and Textiles Division Address all communications to Secretary to the Commission United States International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Executive Summary . v Chapter 1. Introduction . 1-1 Purpose of study . 1-1 Data and scope . 1-1 Organization of study . 1-2 Overview of India’s economy . 1-2 Chapter 2. Structure of the textile and apparel industry . 2-1 Fiber production . 2-1 Textile sector . 2-1 Yarn production . 2-4 Fabric production . 2-4 Dyeing and finishing . 2-5 Apparel sector . 2-5 Structural problems . 2-5 Textile machinery . 2-7 Chapter 3. Government trade and nontrade policies . 3-1 Trade policies . 3-1 Tariff barriers . 3-1 Nontariff barriers . 3-3 Import licensing . 3-3 Customs procedures . 3-5 Marking, labeling, and packaging requirements . 3-5 Export-Import policy . 3-5 Duty entitlement passbook scheme . 3-5 Export promotion capital goods scheme . 3-5 Pre- and post-shipment financing . 3-6 Export processing and special economic zones . 3-6 Nontrade policies . -

Interfacial Adhesion in Rayon/Nylon Sheath/Core Composite Fibers. Weiying Tao Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1991 Interfacial Adhesion in Rayon/Nylon Sheath/Core Composite Fibers. Weiying Tao Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Tao, Weiying, "Interfacial Adhesion in Rayon/Nylon Sheath/Core Composite Fibers." (1991). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5213. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5213 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Immersion Dyeing Nylon and Acetate Rayon Using Prosperse Disperse Dyes Please Read Directions Carefully Before Starting

Immersion Dyeing Nylon and Acetate Rayon using PROsperse Disperse Dyes Please read directions carefully before starting. For medium to dark shades, it is recommended that nylon be dyed with acid dyes, because disperse dyes lack acceptable fastness. Acetate rayon can only be dyed with disperse dyes and has acceptable fastness in all depths of shade with the disperse dyes. All Dyeing should be done in a stainless steel or enamelware container only. Never use aluminum pots. Use Pyrex or stainless steel measuring utensils and a large wooden dowel for stirring in the boiling dye bath. Always do test samples before working on a large project. Please Note: These dyes have the potential to stain any sink that is not made of stainless steel or fireclay ceramic. For additional information, visit our web site at www.prochemicalanddye.com. Wear rubber gloves, apron, or old clothes. Utensils used for dyeing should never be used for food preparation. Supplies PROsperse Disperse Dye Citric Acid Crystals or White Distilled Vinegar Synthrapol PRO Dye Activator or Soda Ash Procedure 1. Scour the fabric by machine washing in HOT 140F (60C) water, or by hand in a pot on the stove with 2 tsp (2 gm) PRO Dye Activator or Soda Ash and 2 tsp (2.5 ml) Synthrapol per pound of fabric (454 gm, or 3 to 4 yards of muslin weight fabric). Rinse thoroughly. This step does not add the dye fixative to the fabric; it prepares your fabric for dyeing by removing any dirt, oil or sizing. 2. Dissolve the dye. Thoroughly dissolve the desired amount of dye powder, from the chart below, in 1 cup (250 ml) of boiling water. -

Colaris Digital Textile Printing

ZIMMER AUSTRIA | DIGITAL PRINTING SYSTEMS COLARIS DIGITAL TEXTILE PRINTING HOME TEXTILES APPAREL DECORATION AUTOMOTIVE FLAGS & BANNERS www.zimmer-austria.com 2020.01.15 page 1 CONTENT 1. INNOVATION IS IN OUR DNA 1.1. HISTORIC MILESTONES 3 2. INK CLASSES 2.1. TYPES | PRODUCTS | PROCESS | REQUIREMENTS 4 2.2. TYPES | PRODUCTS | PROCESS | REQUIREMENTS 5 3. PRINT TECHNOLOGY 3.1. PROCESSING DIAGRAM 6 3.2. PROCESS EQUIPMENT 7 4. REACTIVE PRINTING 4.1. GENERAL INFORMATION 8 4.2. EXAMPLE: TERRY TOWEL PRINT PRODUCTION 9 5. ACID PRINTING 5.1. GENERAL INFORMATION 10 5.2. EXAMPLE: UPHOLSTERY PRINT LINE 11 6. DISPERSE / SUBLIMATION PRINTING 6.1. GENERAL INFORMATION 12 6.2. EXAMPLE: PES BLANKET PRINT LINE 13 7. VAT INDANTHRENE® PRINTING 7.1. GENERAL INFORMATION 14 7.2. APPLICATION DIVERSITY 15 8. PIGMENT PRINTING 8.1. GENERAL INFORMATION 16 8.2. APPLICATION DIVERSITY 17 9. CATIONIC PRINTING 9.1. GENERAL INFORMATION 18 10. COLARIS - CHARACTERISTICS AND FEATURES 10.1. COLARIS MODELS 19 11. COLARIS FEATURES AND COMPONENTS 11.1. INTEGRATED MACHINE COMPONENTS 20 11.2. INTEGRATED MACHINE COMPONENTS 21 12. PROCESS EQUIPMENT 12.1. INLINE COMPONENTS 22 12.2. OFFLINE COMPONENTS 23 13. PRINT HEAD 13.1. TECHNOLOGY 24 13.2. RECONDITION CENTER 25 14. ZIMMER TECHNOLOGY & APPLICATION CENTER 14.1. GENERAL INFORMATION 26 14.2. EQUIPMENT & FACILITIES 27 www.zimmer-austria.com 2020.01.15 page 2 1. INNOVATION IS IN OUR DNA 1.1. HISTORIC MILESTONES Vertical Duplex blanket printer from 1951 First commercial rotary screen printer 1958 The broad digital competence of ZIMMER AUSTRIA is based on an innovation introduced more than 4 decades ago. -

![IS 3781 (1994): Textiles - Honey Comb and Huckaback Towels,Cotton Khadi,Bleached Or Dyed - Specition (Amalgamating IS 3775:1983) [TXD 8: Handloom and Khadi]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6205/is-3781-1994-textiles-honey-comb-and-huckaback-towels-cotton-khadi-bleached-or-dyed-specition-amalgamating-is-3775-1983-txd-8-handloom-and-khadi-1206205.webp)

IS 3781 (1994): Textiles - Honey Comb and Huckaback Towels,Cotton Khadi,Bleached Or Dyed - Specition (Amalgamating IS 3775:1983) [TXD 8: Handloom and Khadi]

इंटरनेट मानक Disclosure to Promote the Right To Information Whereas the Parliament of India has set out to provide a practical regime of right to information for citizens to secure access to information under the control of public authorities, in order to promote transparency and accountability in the working of every public authority, and whereas the attached publication of the Bureau of Indian Standards is of particular interest to the public, particularly disadvantaged communities and those engaged in the pursuit of education and knowledge, the attached public safety standard is made available to promote the timely dissemination of this information in an accurate manner to the public. “जान का अधकार, जी का अधकार” “परा को छोड न 5 तरफ” Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan Jawaharlal Nehru “The Right to Information, The Right to Live” “Step Out From the Old to the New” IS 3781 (1994): Textiles - Honey comb and huckaback towels,cotton khadi,bleached or dyed - Specition (Amalgamating IS 3775:1983) [TXD 8: Handloom and Khadi] “ान $ एक न भारत का नमण” Satyanarayan Gangaram Pitroda “Invent a New India Using Knowledge” “ान एक ऐसा खजाना > जो कभी चराया नह जा सकताह ै”ै Bhartṛhari—Nītiśatakam “Knowledge is such a treasure which cannot be stolen” IS 3781:1994 Indian Standard TEXTILES- HONEYCOMB AND HUCKABACK TOWELS, COTTON KHADI, BLEACHED OR DYED - SPECIFICATION ( First Revision ) UDC 677’21’074’ 162’3 : 645’486 BUREAU OF INDlAN STANDARDS MANAK BHAVAN, 9 BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR MARG NEW DEL,HI 110002 December 1994 Price Group 2 Handloom and Khadi Sectional Committee, TX 08 FOREWORD This Indian Standard ( First Revision ) was adopted by the Bureau of Indian Standards, after the draft finalized by the Handloom and Khadi Sectional Committee had been approved by the Textile Division Council. -

Textile-Dictionary-Full.Pdf

TEXTILE DICTONARY A ABNORMAL CRIMP- A relative term for crimp that is either too low or too high in frequency and/or amplitude or that has been put into the fiber with improper angular characteristics. ABRADED YARN- A filament yarn in which filaments have been cut or broken to create hairiness (fibrillation) to simulate the surface character of spun yarns. Abraded yarns are usually plied or twisted with other yarns before use. ABRASION MARK- An area where a fabric has been damaged by friction. ABRASION RESISTANCE- The ability of a fiber or fabric to withstand surface wear and rubbing. ABSORBANCE- The ability of a substance to transform radiant energy into a different form, usually with a resulting rise in temperature. Mathematically, absorbance is the negative logarithm to the base 10 of transmittance. ABSORBENCY- The ability of one material to take up another material. ABSORPTION- The process of gases or liquids being taken up into the pores of a fiber, yarn, or fabric. ACETIC ACID- An organic acid (CH3COOH) widely used in textile applications. It is used in textile wet processing, dyeing and printing, and in the manufacture of cellulose acetate and cellulose triacetate. ACETIC ANHYDRIDE- Anhydrous acetic acid [(CH3CO)2O]. It is used in the acetylation process in the manufacture of cellulose acetate. ACETONE- Dimethyl ketone (CH3COCH3). One of the most powerful organic solvents. Acetone dissolves secondary cellulose acetate and other derivatives of cellulose. It is miscible with water and has a low boiling point (55-56°). ACID-DYEABLE VARIANTS- Polymers modified chemically to make them receptive to acid dyes.