Clinocardium Nuttallii Class: Bivalvia, Heterodonta, Euheterodonta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

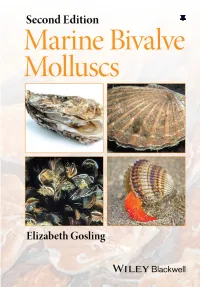

Marine Bivalve Molluscs

Marine Bivalve Molluscs Marine Bivalve Molluscs Second Edition Elizabeth Gosling This edition first published 2015 © 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd First edition published 2003 © Fishing News Books, a division of Blackwell Publishing Registered Office John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030‐5774, USA For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley‐blackwell. The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author(s) have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. -

Paleoenvironmental Interpretation of Late Glacial and Post

PALEOENVIRONMENTAL INTERPRETATION OF LATE GLACIAL AND POST- GLACIAL FOSSIL MARINE MOLLUSCS, EUREKA SOUND, CANADIAN ARCTIC ARCHIPELAGO A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the Department of Geography University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Shanshan Cai © Copyright Shanshan Cai, April 2006. All rights reserved. i PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Geography University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 i ABSTRACT A total of 5065 specimens (5018 valves of bivalve and 47 gastropod shells) have been identified and classified into 27 species from 55 samples collected from raised glaciomarine and estuarine sediments, and glacial tills. -

Download PDF Version

MarLIN Marine Information Network Information on the species and habitats around the coasts and sea of the British Isles Lagoon cockle (Cerastoderma glaucum) MarLIN – Marine Life Information Network Biology and Sensitivity Key Information Review Nicola White 2002-07-15 A report from: The Marine Life Information Network, Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. Please note. This MarESA report is a dated version of the online review. Please refer to the website for the most up-to-date version [https://www.marlin.ac.uk/species/detail/1315]. All terms and the MarESA methodology are outlined on the website (https://www.marlin.ac.uk) This review can be cited as: White, N. 2002. Cerastoderma glaucum Lagoon cockle. In Tyler-Walters H. and Hiscock K. (eds) Marine Life Information Network: Biology and Sensitivity Key Information Reviews, [on-line]. Plymouth: Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. DOI https://dx.doi.org/10.17031/marlinsp.1315.1 The information (TEXT ONLY) provided by the Marine Life Information Network (MarLIN) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. Note that images and other media featured on this page are each governed by their own terms and conditions and they may or may not be available for reuse. Permissions beyond the scope of this license are available here. Based on a work at www.marlin.ac.uk (page left blank) Date: 2002-07-15 Lagoon cockle (Cerastoderma glaucum) - Marine Life Information Network See online review for distribution map Three Cerastoderma glaucum with siphons extended. Distribution data supplied by the Ocean Photographer: Dennis R. -

Bankia Setacea Class: Bivalvia, Heterodonta, Euheterodonta

Phylum: Mollusca Bankia setacea Class: Bivalvia, Heterodonta, Euheterodonta Order: Imparidentia, Myida The northwest or feathery shipworm Family: Pholadoidea, Teredinidae, Bankiinae Taxonomy: The original binomen for Bankia the presence of long siphons. Members of setacea was Xylotrya setacea, described by the family Teredinidae are modified for and Tryon in 1863 (Turner 1966). William Leach distiguished by a wood-boring mode of life described several molluscan genera, includ- (Sipe et al. 2000), pallets at the siphon tips ing Xylotrya, but how his descriptions were (see Plate 394C, Coan and Valentich-Scott interpreted varied. Although Menke be- 2007) and distinct anterior shell indentation. lieved Xylotrya to be a member of the Phola- They are commonly called shipworms (though didae, Gray understood it as a member of they are not worms at all!) and bore into many the Terdinidae and synonyimized it with the wooden structures. The common name ship- genus Bankia, a genus designated by the worm is based on their vermiform morphology latter author in 1842. Most authors refer to and a shell that only covers the anterior body Bankia setacea (e.g. Kozloff 1993; Sipe et (Ricketts and Calvin 1952; see images in al. 2000; Coan and Valentich-Scott 2007; Turner 1966). Betcher et al. 2012; Borges et al. 2012; Da- Body: Bizarrely modified bivalve with re- vidson and de Rivera 2012), although one duced, sub-globular body. For internal anato- recent paper sites Xylotrya setacea (Siddall my, see Fig. 1, Canadian…; Fig. 1 Betcher et et al. 2009). Two additional known syno- al. 2012. nyms exist currently, including Bankia Color: osumiensis, B. -

The West African Enigma: Systematics, Evolution, and Palaeobiogeography of Cardiid Bivalve Procardium

The West African enigma: Systematics, evolution, and palaeobiogeography of cardiid bivalve Procardium JAN JOHAN TER POORTEN and RAFAEL LA PERNA Poorten, J.J. ter and La Perna, R. 2017. The West African enigma: Systematics, evolution, and palaeobiogeography of cardiid bivalve Procardium. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 62 (4): 729–757. Procardium gen. nov. is proposed for a group of early Miocene to Recent large cardiids in the subfamily Cardiinae. The type species is Cardium indicum, the only living representative, previously assigned to the genus Cardium. It is a mainly West African species, with a very limited occurrence in the westernmost Mediterranean. Procardium gen. nov. and Cardium differ markedly with regard to shell characters and have distinct evolutionary and biogeographic histories. Six species, in the early Miocene to Pleistocene range, and one Recent species are assigned to the new genus: Procardium magnei sp. nov., P. jansseni sp. nov., P. danubianum, P. kunstleri, P. avisanense, P. diluvianum, and P. indicum. During the Miocene, Procardium gen. nov. had a wide distribution in Europe, including the Proto-Mediterranean Sea, Western and Central Paratethys and NE Atlantic, with a maximum diversity during the Langhian and Serravallian. Its palaeobio- geographic history was strongly controlled by climate. During the Langhian stage, warm conditions allowed the genus to reach its highest latitude, ca. 54° N, in the southern North Sea Basin. With cooling, its latitudinal range gradually retreated southward, becoming mainly Mediterranean in the Pliocene–Pleistocene, and West African at present. Key words: Bivalvia, Cardiidae, systematics, Neogene, Quaternary, Africa, Europe. Jan Johan ter Poorten [[email protected]], Integrative Research Center, Field Museum of Natural History, Chica- go, IL 60605, USA. -

Spatial Variability in Recruitment of an Infaunal Bivalve

Spatial Variability in Recruitment of an Infaunal Bivalve: Experimental Effects of Predator Exclusion on the Softshell Clam (Mya arenaria L.) along Three Tidal Estuaries in Southern Maine, USA Author(s): Brian F. Beal, Chad R. Coffin, Sara F. Randall, Clint A. Goodenow Jr., Kyle E. Pepperman, Bennett W. Ellis, Cody B. Jourdet and George C. Protopopescu Source: Journal of Shellfish Research, 37(1):1-27. Published By: National Shellfisheries Association https://doi.org/10.2983/035.037.0101 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.2983/035.037.0101 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Journal of Shellfish Research, Vol. 37, No. 1, 1–27, 2018. SPATIAL VARIABILITY IN RECRUITMENT OF AN INFAUNAL BIVALVE: EXPERIMENTAL EFFECTS OF PREDATOR EXCLUSION ON THE SOFTSHELL CLAM (MYA ARENARIA L.) ALONG THREE TIDAL ESTUARIES IN SOUTHERN MAINE, USA 1,2 3 2 3 BRIAN F. -

South Carolina Department of Natural Resources

FOREWORD Abundant fish and wildlife, unbroken coastal vistas, miles of scenic rivers, swamps and mountains open to exploration, and well-tended forests and fields…these resources enhance the quality of life that makes South Carolina a place people want to call home. We know our state’s natural resources are a primary reason that individuals and businesses choose to locate here. They are drawn to the high quality natural resources that South Carolinians love and appreciate. The quality of our state’s natural resources is no accident. It is the result of hard work and sound stewardship on the part of many citizens and agencies. The 20th century brought many changes to South Carolina; some of these changes had devastating results to the land. However, people rose to the challenge of restoring our resources. Over the past several decades, deer, wood duck and wild turkey populations have been restored, striped bass populations have recovered, the bald eagle has returned and more than half a million acres of wildlife habitat has been conserved. We in South Carolina are particularly proud of our accomplishments as we prepare to celebrate, in 2006, the 100th anniversary of game and fish law enforcement and management by the state of South Carolina. Since its inception, the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) has undergone several reorganizations and name changes; however, more has changed in this state than the department’s name. According to the US Census Bureau, the South Carolina’s population has almost doubled since 1950 and the majority of our citizens now live in urban areas. -

Molluscs (Mollusca: Gastropoda, Bivalvia, Polyplacophora)

Gulf of Mexico Science Volume 34 Article 4 Number 1 Number 1/2 (Combined Issue) 2018 Molluscs (Mollusca: Gastropoda, Bivalvia, Polyplacophora) of Laguna Madre, Tamaulipas, Mexico: Spatial and Temporal Distribution Martha Reguero Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Andrea Raz-Guzmán Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México DOI: 10.18785/goms.3401.04 Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/goms Recommended Citation Reguero, M. and A. Raz-Guzmán. 2018. Molluscs (Mollusca: Gastropoda, Bivalvia, Polyplacophora) of Laguna Madre, Tamaulipas, Mexico: Spatial and Temporal Distribution. Gulf of Mexico Science 34 (1). Retrieved from https://aquila.usm.edu/goms/vol34/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gulf of Mexico Science by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reguero and Raz-Guzmán: Molluscs (Mollusca: Gastropoda, Bivalvia, Polyplacophora) of Lagu Gulf of Mexico Science, 2018(1), pp. 32–55 Molluscs (Mollusca: Gastropoda, Bivalvia, Polyplacophora) of Laguna Madre, Tamaulipas, Mexico: Spatial and Temporal Distribution MARTHA REGUERO AND ANDREA RAZ-GUZMA´ N Molluscs were collected in Laguna Madre from seagrass beds, macroalgae, and bare substrates with a Renfro beam net and an otter trawl. The species list includes 96 species and 48 families. Six species are dominant (Bittiolum varium, Costoanachis semiplicata, Brachidontes exustus, Crassostrea virginica, Chione cancellata, and Mulinia lateralis) and 25 are commercially important (e.g., Strombus alatus, Busycoarctum coarctatum, Triplofusus giganteus, Anadara transversa, Noetia ponderosa, Brachidontes exustus, Crassostrea virginica, Argopecten irradians, Argopecten gibbus, Chione cancellata, Mercenaria campechiensis, and Rangia flexuosa). -

Ультраструктура Сперматозоидов Четырех Видов Двустворчатых Моллюсков – Представителей Семейств Cardiidae И Astartidae Из Японского Моря С.А

Бюллетень Дальневосточного The Bulletin of the Russian малакологического общества Far East Malacological Society 2012, вып. 15/16, с. 176–182 2012, vol. 15/16, pp. 176–182 Ультраструктура сперматозоидов четырех видов двустворчатых моллюсков – представителей семейств Cardiidae и Astartidae из Японского моря С.А. Тюрин1, А.Л. Дроздов1,2 1Институт биологии моря им. А.В. Жирмунского ДВО РАН, Владивосток 690059, Россия 2Дальневосточный федеральный университет, Владивосток, 690950, Россия e-mail: [email protected] Изучена ультраструктура спермиев четырех видов двустворчатых моллюсков из семейств Cardiidae (Serripes groenlandicus, Clinocardium californiense, Clinocardium ciliatum) и Astartidae (Astarte borealis). Показано, что описанные спермии представляют собой классические акваспер- мии и состоят из головки, средней части и хвоста. Форма головки варьирует от конической изо- гнутой (сем. Cardiidae) до стержневидной (сем. Astartidae). Средняя часть имеет сходное строение и представлена четырьмя митохондриями, которые окружают перпендикулярно расположенные центриоли, от дистальной центриоли берет начало аксонема. Коническая изогнутая форма головки спермиев у представителей сем. Cardiidae подтверждает ранее опубликованные данные. Сравни- тельный анализ строения спермиев двустворчатых моллюсков свидетельствует о специфичности формы сперматозоидов для семейств. Ключевые слова: двустворчатые моллюски, Cardiidae, Astartidae, строение спермиев, Япон- ское море. Spermatozoa ultrastructure of four bivalve species of the families Cardiidae and Astartidae from the Sea of Japan S.A. Tyurin1, A.L. Drozdov1,2 1A.V. Zhirmunsky Institute of Marine Biology, Far East Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, Vladivostok 690059, Russia 2Far Eastern Federal University, Vladivostok 690950, Russia e-mail: [email protected] Sperm ultrastructure of three bivalve mollusks of the family Cardiidae (Serripes groenlandicus, Clino- cardium californiense, Clinocardium ciliatum), and one species of the family Astartidae (Astarte borealis) from the Sea of Japan was examined. -

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES an Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES An Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals By Paul Rudy, Jr. Lynn Hay Rudy Oregon Institute of Marine Biology University of Oregon Charleston, Oregon 97420 Contract No. 79-111 Project Officer Jay F. Watson U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 500 N.E. Multnomah Street Portland, Oregon 97232 Performed for National Coastal Ecosystems Team Office of Biological Services Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 Table of Contents Introduction CNIDARIA Hydrozoa Aequorea aequorea ................................................................ 6 Obelia longissima .................................................................. 8 Polyorchis penicillatus 10 Tubularia crocea ................................................................. 12 Anthozoa Anthopleura artemisia ................................. 14 Anthopleura elegantissima .................................................. 16 Haliplanella luciae .................................................................. 18 Nematostella vectensis ......................................................... 20 Metridium senile .................................................................... 22 NEMERTEA Amphiporus imparispinosus ................................................ 24 Carinoma mutabilis ................................................................ 26 Cerebratulus californiensis .................................................. 28 Lineus ruber ......................................................................... -

Benthic Data Sheet

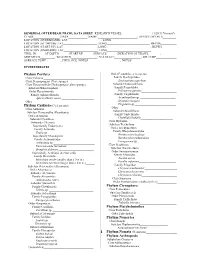

DEMERSAL OTTER/BEAM TRAWL DATA SHEET RESEARCH VESSEL_____________________(1/20/13 Version*) CLASS__________________;DATE_____________;NAME:___________________________; DEVICE DETAILS_________ LOCATION (OVERBOARD): LAT_______________________; LONG______________________________ LOCATION (AT DEPTH): LAT_______________________; LONG_____________________________; DEPTH___________ LOCATION (START UP): LAT_______________________; LONG______________________________;.DEPTH__________ LOCATION (ONBOARD): LAT_______________________; LONG______________________________ TIME: IN______AT DEPTH_______START UP_______SURFACE_______.DURATION OF TRAWL________; SHIP SPEED__________; WEATHER__________________; SEA STATE__________________; AIR TEMP______________ SURFACE TEMP__________; PHYS. OCE. NOTES______________________; NOTES_______________________________ INVERTEBRATES Phylum Porifera Order Pennatulacea (sea pens) Class Calcarea __________________________________ Family Stachyptilidae Class Demospongiae (Vase sponge) _________________ Stachyptilum superbum_____________________ Class Hexactinellida (Hyalospongia- glass sponge) Suborder Subsessiliflorae Subclass Hexasterophora Family Pennatulidae Order Hexactinosida Ptilosarcus gurneyi________________________ Family Aphrocallistidae Family Virgulariidae Aphrocallistes vastus ______________________ Acanthoptilum sp. ________________________ Other__________________________________________ Stylatula elongata_________________________ Phylum Cnidaria (Coelenterata) Virgularia sp.____________________________ Other_______________________________________ -

Известия Тинро Удк 574.583(265.53) Т.С. Шпилько1, Г

Известия ТИНРО 2018 Том 195 УДК 574.583(265.53) Т.С. Шпилько1, Г.В. Шевченко1, 2* 1 Сахалинский научно-исследовательский институт рыбного хозяйства и океанографии, 693023, г. Южно-Сахалинск, ул. Комсомольская, 196; 2 Институт морской геологии и геофизики ДВО РАН, 693022, г. Южно-Сахалинск, ул. Науки, 1Б ВЛИЯНИЕ ПРИЛИВО-ОТЛИВНОЙ ДИНАМИКИ НА ОБМЕН МЕРОПЛАНКТОНА (BIVALVIA, GASTROPODA) МЕЖДУ ЛАГУНОЙ БУССЕ И ПРИЛЕГАЮЩЕЙ МОРСКОЙ АКВАТОРИЕЙ ЗАЛИВА АНИВА По результатам планктонной съемки, проведенной в 2014 г. в протоке Суслова, да- ется описание обмена личиночным материалом (Bivalvia, Gastropoda) между зал. Анива и лагуной Буссе. Приводится характеристика приливного водообмена. На основе при- ливных уровней и площади зеркала лагуны получены оценки общего затока морских вод для каждого исследуемого приливного цикла. Основным фактором обмена личиночным материалом являются высокие скорости приливного течения (достигающие, по оценке, 4 уз) как на приливе, так и на отливе. Лагунные виды меропланктона на отливе выносятся течением достаточно далеко от протоки в морское прибрежье, и обратный занос этих видов на фазе прилива становится маловероятным. В результате исследования уста- новлено, что вследствие мелководности лагуны Буссе в ней происходит более быстрый прогрев воды в июле, и нерест лагунных видов начинается раньше, чем в зал. Анива. В августе при максимальном годовом прогреве воды численность диагностированных видов моллюсков увеличивается независимо от их зонально-географической принадлежности, характеризуется синхронностью и соответствует в лагуне Буссе и в зал. Анива самому теплому времени года. В сентябре наблюдаются наименьшие показатели заноса и вы- носа как двустворчатых, так и брюхоногих моллюсков. Описан таксономический состав и сезонная динамика личинок двустворчатых и брюхоногих моллюсков. Ключевые слова: лагуна, протока, прилив, течение, меропланктон, двустворчатые моллюски, брюхоногие моллюски, личинки.