Degree Project Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malleus Monstrorumsampleexpanded English File Edition Is Published by Chaosium Inc

Sample file —EXPANDED ENGLISH EDITION IN 380 ENTRIES— by Scott David Aniolowski with Sandy Petersen & Lynn Willis Additional Material by: David Conyers, Keith Herber, Kevin Ross, ChadSample J. Bowser, Shannon file Appel, Christian von Aster, Joachim A. Hagen, Florian Hardt, Frank Heller, Peter Schott, Steffen Schuütte, Michael Siefner, Jan Cristof Steines, Holger Göttmann, Wolfang Schiemichen, Ingo Ahrens, and friends. For fuller Author credits see pages 4 and 288. Project & Layout: Charlie Krank Cover Painting: Lee Gibbons Illustrated by: Pascal D. Bohr, Konstantyn Debus, Nils Eckhardt, Thomas Ertmer, Kostja Kleye, Jan Kluczewitz, Christian Küttler, Klaas Neumann, Patrick Strietzel, Jens Weber, Maria Luisa Witte, Lydia Ortiz, Paul Carrick. Art direction and visual concept: Konstantyn Debus (www.yllustration.com) Participants in the German Edition: Frank Heller, Konstantyn Debus, Peter Schott, Thomas M. Webhofer, Ingo Ahrens, Jens Kaufmann, Holger Göttmann, Christina Wessel, Maik Krüger, Holger Rinke, Andreas Finkernagel, 15brötchenmann Find more information at www.pegasus.de German to English Translation: Bill Walsh Layout Assistance: Alan Peña, Lydia Ortiz Chaosium is: Lynn Willis, Charlie Krank, Dustin Wright, Fergie, and a few odd critters. A CHAOSIUM PUBLICATION • 2006 M’bwa, megalodon, the Million Favoured Ones, the Complete Credits mind parasites, the miri nigri, M’nagalah, Mordiggian, moose, M’Tlblys, the nioth-korghai, Nug & Yeb, octo- Scott David Aniolowski: the children of Abhoth, pus, Ossadagowah, Othuum, the minions of Othuum, -

Spectres of Darwin: HP Lovecraft's Nihilistic Parody

spectres of Darwin: H. P. Lovecraft's Nihilistic parody of Religion by Dustin Geeraert A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in paftial fulfilment of the requirenrents of the degree of Master of Arts Deparlment of English, Film and Theatre University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Copyright @ 2010 by Dustin Geeraed THE UI..{IVERSITY OF MAI\ITOBA FACTiLTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES COPYIìIGHT PERMISSION Spectres of Darwin: H. P. Lovecraft's Nihilistic parody of Religion By Dustin Geeraert A Thesis/Pl'acticr¡m subrnittecl to thc Faculty of Gr¿rtluate Studies of The flniversity of M¿rnitob¿r in ¡rarti:rl fìrlfillment of thc rcquircment of thc degl.ec of Master of Arts Drrstin GceraertO20l0 Pel'lrlissiotl h¿rs beetr granted to the University of M¿rnitob¿r Libr.¿rries to lenrl ¿ì cop¡, gf'this thesis/¡rracticurn, to Librarr'¿rnd Archives can¿rda (LAC) to leud ¿ì cop]¡ of.this thesis/¡rracticurn, ¿rntl to LAC's:rgcnt (UMI/ProQrrest) to microfilm, sellcopies ¿rnrl to ¡rublish ¿rn abstract of'this thesis/¡rracticu m. This re¡rrotluction or copy of this thesis h¿rs been m¿rtlc ¿rvailable b5, iruthorit5, of the copl,right or\/net'solell' for the purpose of ¡rrir,:rte stutll'antl research, ¿ìn(l rn¿ìr,onlv bc repro{uccrt :iria copied as ¡rermitted by copyright l:rrvs or n'ith express u'ritten authorization fì-om ffic co¡ryright o¡,ner. Contents Introduction..... ...........3 Chapter 1: Lovecraft's Nietzscheanism and Nihilism..... .....18 Chapter 2: Sanity, Superstition, and the Supernatural. ..........37 Chapter 3: His Kingdom Come. -

Pandemic: Reign of Cthulhu Rulebook

Beings of ancient and bizarre intelligence, known as Old Ones, are stirring within their vast cosmic prisons. If they awake into the world, it will unleash an age of madness, chaos, and destruction upon the very fabric of reality. Everything you know and love will be destroyed! You are cursed with knowledge that the “sleeping masses” cannot bear: that this Evil exists, and that it must be stopped at all costs. Shadows danced all around the gas street light above you as the pilot flame sputtered a weak yellow light. Even a small pool of light is better than total darkness, you think to yourself. You check your watch again for the third time in the last few minutes. Where was she? Had something happened? The sound of heels clicking on pavement draws your eyes across the street. Slowly, as if the darkness were a cloak around her, a woman comes into view. Her brown hair rests in a neat bun on her head and glasses frame a nervous face. Her hands hold a large manila folder with the words INNSMOUTH stamped on the outside in blocky type lettering. “You’re late,” you say with a note of worry in your voice, taking the folder she is handing you. “I… I tried to get here as soon as I could.” Her voice is tight with fear, high pitched and fast, her eyes moving nervously without pause. “You know how to fix this?” The question in her voice cuts you like a knife. “You can… make IT go away?!” You wince inwardly as her voice raises too loudly at that last bit, a nervous edge of hysteria creeping into her tone. -

Machen, Lovecraft, and Evolutionary Theory

i DEADLY LIGHT: MACHEN, LOVECRAFT, AND EVOLUTIONARY THEORY Jessica George A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy School of English, Communication and Philosophy Cardiff University March 2014 ii Abstract This thesis explores the relationship between evolutionary theory and the weird tale in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Through readings of works by two of the writers most closely associated with the form, Arthur Machen (1863-1947) and H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937), it argues that the weird tale engages consciously, even obsessively, with evolutionary theory and with its implications for the nature and status of the “human”. The introduction first explores the designation “weird tale”, arguing that it is perhaps less useful as a genre classification than as a moment in the reception of an idea, one in which the possible necessity of recalibrating our concept of the real is raised. In the aftermath of evolutionary theory, such a moment gave rise to anxieties around the nature and future of the “human” that took their life from its distant past. It goes on to discuss some of the studies which have considered these anxieties in relation to the Victorian novel and the late-nineteenth-century Gothic, and to argue that a similar full-length study of the weird work of Machen and Lovecraft is overdue. The first chapter considers the figure of the pre-human survival in Machen’s tales of lost races and pre-Christian religions, arguing that the figure of the fairy as pre-Celtic survival served as a focal point both for the anxieties surrounding humanity’s animal origins and for an unacknowledged attraction to the primitive Other. -

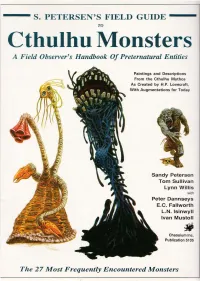

Cthulhu Monsters a Field Observer's Handbook of Preternatural Entities

--- S. PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO Cthulhu Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Paintings and Descriptions From the Cthulhu Mythos As Created by H.P. Lovecraft, With Augmentations for Today Sandy Petersen Tom Sullivan Lynn Willis with Peter Dannseys E.C. Fallworth L.N. Isinwyll Ivan Mustoll Chaosium Inc. Publication 5105 The 27 Most Frequently Encountered Monsters Howard Phillips Lovecraft 1890 - 1937 t PETERSEN'S Field Guide To Cthulhu :Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Sandy Petersen conception and text TOIn Sullivan 27 original paintings, most other drawings Lynn ~illis project, additional text, editorial, layout, production Chaosiurn Inc. 1988 The FIELD GUIDe is p «blished by Chaosium IIIC . • PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO CfHUU/U MONSTERS is copyrighl e1988 try Chaosium IIIC.; all rights reserved. _ Similarities between characters in lhe FIELD GUIDE and persons living or dead are strictly coincidental . • Brian Lumley first created the ChJhoniwu . • H.P. Lovecraft's works are copyright e 1963, 1964, 1965 by August Derleth and are quoted for purposes of ilIustraJion_ • IflCide ntal monster silhouelles are by Lisa A. Free or Tom SU/livQII, and are copyright try them. Ron Leming drew the illustraJion of H.P. Lovecraft QIId tlu! sketclu!s on p. 25. _ Except in this p«blicaJion and relaJed advertising, artwork. origillalto the FIELD GUIDE remains the property of the artist; all rights reserved . • Tire reproductwn of material within this book. for the purposes of personal. or corporaJe profit, try photographic, electronic, or other methods of retrieval, is prohibited . • Address questions WId commel11s cOlICerning this book. -

Mi-Go 1 Mi-Go

Mi-go 1 Mi-go An interpretation of the Mi-Go by Ruud Dirven Mi-go ("The Abominable Ones") is a Himalayan nickname for a race of extraterrestrials in the Cthulhu Mythos created by H. P. Lovecraft and others. The name was first applied to the creatures in Lovecraft's short story "The Whisperer in Darkness" (1931), elaborating on a reference to 'What fungi sprout in Yuggoth' in his sonnet cycle Fungi from Yuggoth (1929–30) which described the contrasting vegetation on alien dream-worlds. Summary The "Mi-go" are large, pinkish, fungoid, crustacean-like entities the size of a man; where a head would be, they have a "convoluted ellipsoid" composed of pyramided, fleshy rings and covered in antennae. According to two reports in the original short story, their bodies consist of a form of matter that does not occur naturally on Earth; for this reason, they do not register on ordinary photographic film. They are capable of going into suspended animation until softened and reheated by the sun or some other source of heat. They are about five feet (1.5 m) long, and their crustacean-like bodies bear numerous sets of paired appendages. They possess a pair of membranous bat-like wings which are used to fly through the "aether" of outer space (a scientific concept which is now discredited). The wings do not function well on Earth. Several other races in Lovecraft's Mythos also have wings like these. The Mi-go can transport humans from Earth to Pluto (and beyond) and back again by removing the subject's brain and placing it into a "brain cylinder", which can be attached to external devices to allow it to see, hear, and speak. -

EURAMERICA Vol

EURAMERICA Vol. 39, No. 1 (March 2009), 1-27 http://euramerica.ea.sinica.edu.tw/ © Institute of European and American Studies, Academia Sinica On At the Mountains of Madness —Enveloping the Cosmic Horror Chia Yi Lee Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures National Chiao Tung University 1001 University Road, Hsinchu 30010, Taiwan E-mail: [email protected] Abstract As the culmination of H. P. Lovecraft’s late style in delineating the cosmic horror, At the Mountains of Madness poses several questions, the most interesting of which may concern the story’s narrative efficacy in evoking horror that has been presented in the form of science fiction or, to be more precise, in scientific realism. The pivot of this narrative revolves round the novelette’s central sections (7 and 8) where a genealogy of the sentient entities that precede humans’ earthly emergence is recorded. Whether the genealogical enveloping of the cosmic other can summon up the cosmic horror as is textually intended, and what function the enveloping plays against the backdrop of the story as a whole—these will be the main concerns of this paper. Key Words: horror, science, supplementarity Received April 7, 2008; accepted June 10, 2008; last revised July 10, 2008 Proofreaders: Jeffrey Cuvilier, Hsueh-mei Chen, Chia-chi Tseng, Ying-tzu Chang 2 EURAMERICA I H. P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness is one of his longest works, at around 50,000 words, which would have made it suitable for publication as a single-volume novelette. Yet ironically, by the time of Lovecraft’s death in 1937, only one book with his name stamped on cover had been published (Joshi, 1999: 264). -

Cthulhu Lives!: a Descriptive Study of the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society

CTHULHU LIVES!: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF THE H.P. LOVECRAFT HISTORICAL SOCIETY J. Michael Bestul A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Dr. Jane Barnette, Advisor Prof. Bradford Clark Dr. Marilyn Motz ii ABSTRACT Dr. Jane Barnette, Advisor Outside of the boom in video game studies, the realm of gaming has barely been scratched by academics and rarely been explored in a scholarly fashion. Despite the rich vein of possibilities for study that tabletop and live-action role-playing games present, few scholars have dug deeply. The goal of this study is to start digging. Operating at the crossroads of art and entertainment, theatre and gaming, work and play, it seeks to add the live-action role-playing game, CTHULHU LIVES, to the discussion of performance studies. As an introduction, this study seeks to describe exactly what CTHULHU LIVES was and has become, and how its existence brought about the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society. Simply as a gaming group which grew into a creative organization that produces artifacts in multiple mediums, the Society is worthy of scholarship. Add its humble beginnings, casual style and non-corporate affiliation, and its recent turn to self- sustainability, and the Society becomes even more interesting. In interviews with the artists behind CTHULHU LIVES, and poring through the archives of their gaming experiences, the picture develops of the journey from a small group of friends to an organization with influences and products on an international scale. -

The Weird and Monstrous Names of HP Lovecraft Christopher L Robinson HEC-Paris, France

names, Vol. 58 No. 3, September, 2010, 127–38 Teratonymy: The Weird and Monstrous Names of HP Lovecraft Christopher L Robinson HEC-Paris, France Lovecraft’s teratonyms are monstrous inventions that estrange the sound patterns of English and obscure the kinds of meaning traditionally associ- ated with literary onomastics. J.R.R. Tolkien’s notion of linguistic style pro- vides a useful concept to examine how these names play upon a distance from and proximity to English, so as to give rise to specific historical and cultural connotations. Some imitate the sounds and forms of foreign nomen- clatures that hold “weird” connotations due to being linked in the popular imagination with kabbalism and decadent antiquity. Others introduce sounds-patterns that lie outside English phonetics or run contrary to the phonotactics of the language to result in anti-aesthetic constructions that are awkward to pronounce. In terms of sense, teratonyms invite comparison with the “esoteric” words discussed by Jean-Jacques Lecercle, as they dimi- nish or obscure semantic content, while augmenting affective values and heightening the reader’s awareness of the bodily production of speech. keywords literary onomastics, linguistic invention, HP Lovecraft, twentieth- century literature, American literature, weird fiction, horror fiction, teratology Text Cult author H.P. Lovecraft is best known as the creator of an original mythology often referred to as the “Cthulhu Mythos.” Named after his most popular creature, this mythos is elaborated throughout Lovecraft’s poetry and fiction with the help of three “devices.” The first is an outlandish array of monsters of extraterrestrial origin, such as Cthulhu itself, described as “vaguely anthropoid [in] outline, but with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers, a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind” (1963: 134). -

The Rats in the Walls by H. P. Lovecraft

The Rats in the Walls by H. P. Lovecraft Written Aug-Sep 1923 Published in March 1924 in Weird Tales, Vol. 3, No. 3, p. 25-31. On 16 July 1923, I moved into Exham Priory after the last workman had finished his labours. The restoration had been a stupendous task, for little had remained of the deserted pile but a shell-like ruin; yet because it had been the seat of my ancestors, I let no expense deter me. The place had not been inhabited since the reign of James the First, when a tragedy of intensely hideous, though largely unexplained, nature had struck down the master, five of his children, and several servants; and driven forth under a cloud of suspicion and terror the third son, my lineal progenitor and the only survivor of the abhorred line. With this sole heir denounced as a murderer, the estate had reverted to the crown, nor had the accused man made any attempt to exculpate himself or regain his property. Shaken by some horror greater than that of conscience or the law, and expressing only a frantic wish to exclude the ancient edifice from his sight and memory, Walter de la Poer, eleventh Baron Exham, fled to Virginia and there founded the family which by the next century had become known as Delapore. Exham Priory had remained untenanted, though later allotted to the estates of the Norrys family and much studied because of its peculiarly composite architecture; an architecture involving Gothic towers resting on a Saxon or Romanesque substructure, whose foundation in turn was of a still earlier order or blend of orders -- Roman, and even Druidic or native Cymric, if legends speak truly. -

Errata for H. P. Lovecraft: the Fiction

Errata for H. P. Lovecraft: The Fiction The layout of the stories – specifically, the fact that the first line is printed in all capitals – has some drawbacks. In most cases, it doesn’t matter, but in “A Reminiscence of Dr. Samuel Johnson”, there is no way of telling that “Privilege” and “Reminiscence” are spelled with capitals. THE BEAST IN THE CAVE A REMINISCENCE OF DR. SAMUEL JOHNSON 2.39-3.1: advanced, and the animal] advanced, 28.10: THE PRIVILEGE OF REMINISCENCE, the animal HOWEVER] THE PRIVILEGE OF 5.12: wondered if the unnatural quality] REMINISCENCE, HOWEVER wondered if this unnatural quality 28.12: occurrences of History and the] occurrences of History, and the THE ALCHEMIST 28.20: whose famous personages I was] whose 6.5: Comtes de C——“), and] Comtes de C— famous Personages I was —”), and 28.22: of August 1690 (or] of August, 1690 (or 6.14: stronghold for he proud] stronghold for 28.32: appear in print.”), and] appear in the proud Print.”), and 6.24: stones of he walls,] stones of the walls, 28.34: Juvenal, intituled “London,” by] 7.1: died at birth,] died at my birth, Juvenal, intitul’d “London,” by 7.1-2: servitor, and old and trusted] servitor, an 29.29: Poems, Mr. Johnson said:] Poems, Mr. old and trusted Johnson said: 7.33: which he had said had for] which he said 30.24: speaking for Davy when others] had for speaking for Davy when others 8.28: the Comte, the pronounced in] the 30.25-26: no Doubt but that he] no Doubt that Comte, he pronounced in he 8.29: haunted the House of] haunted the house 30.35-36: to the Greater -

H. P. Lovecraft-A Bibliography.Pdf

X-'r Art Hi H. P. LOVECRAFT; A BIBLIOGRAPHY compiled by Joseph Payne/ Brennan Yale University Library BIBLIO PRESS 1104 Vermont Avenue, N. W. Washington 5, D. C. Revised edition, copyright 1952 Joseph Payne Brennan Original from Digitized by GOO UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA L&11 vie 2. THE SHUNNED HOUSE. Athol, Mass., 1928. bds., labels, uncut. o. p. August Derleth: "Not a published book. Six or seven copies hand bound by R. H. Barlow in 1936 and sent to friends." Some stapled in paper covers. A certain number of uncut, unbound but folded sheets available. Following is an extract from the copyright notice pasted to the unbound sheets: "Though the sheets of this story were printed and marked for copyright in 1928, the story was neither bound nor cir- culated at that time. A few copies were bound, put under copyright, and circulated by R. H. Barlow in 1936, but the first wide publication of the story was in the magazine, WEIRD TALES, in the following year. The story was orig- inally set up and printed by the late W. Paul Cook, pub- lisher of THE RECLUSE." FURTHER CRITICISM OF POETRY. Press of Geo. G. Fetter Co., Louisville, 1952. 13 p. o. p. THE CATS OF ULTHAR. Dragonfly Press, Cassia, Florida, 1935. 10 p. o. p. Christmas, 1935. Forty copies printed. LOOKING BACKWARD. C. W. Smith, Haverhill, Mass., 1935. 36 p. o. p. THE SHADOW OVER INNSMOUTH. Visionary Press, Everett, Pa., 1936. 158 p. o. p. Illustrations by Frank Utpatel. The only work of the author's which was published in book form during his lifetime.