The History of Lowell House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Debating Diversity Following the Widely Publicized Deaths of Black Tape

KENNEDY SCHOOL, UNDER CONSTRUCTION. The Harvard Kennedy School aims to build students’ capacity for better public policy, wise democratic governance, international amity, and more. Now it is addressing its own capacity issues (as described at harvardmag.com/ hks-16). In January, as seen across Eliot Street from the northeast (opposite page), work was well under way to raise the level of the interior courtyard, install utility space in a new below-grade level, and erect a four-story “south building.” The project will bridge the Eliot Street opening between the Belfer (left) and Taubman (right) buildings with a new “gateway” structure that includes faculty offices and other spaces. The images on this page (above and upper right) show views diagonally across the courtyard from Taubman toward Littauer, and vice versa. Turning west, across the courtyard toward the Charles Hotel complex (right), affords a look at the current open space between buildings; the gap is to be filled with a new, connective academic building, including classrooms. Debating Diversity following the widely publicized deaths of black tape. The same day, College dean Toward a more inclusive Harvard African-American men and women at the Rakesh Khurana distributed to undergrad- hands of police. Particularly last semester, uates the results of an 18-month study on di- Amid widely publicized student protests a new wave of activism, and the University’s versity at the College. The day before, Presi- on campuses around the country in the last responses to it, have invited members of the dent Drew Faust had joined students at a year and a half, many of them animated by Harvard community on all sides of the is- rally in solidarity with racial-justice activ- concerns about racial and class inequities, sues to confront the challenges of inclusion. -

Harvard Square Cambridge, Ma 5 Jfk St & 24 Brattle St

HARVARD SQUARE CAMBRIDGE, MA 5 JFK ST & 24 BRATTLE ST. RETAIL FOR LEASE 600 – 11,000 SF SUBDIVIDABLE THE ABBOT is THE epicenter of Harvard Square. This iconic property is undergoing a complete redevelopment to create an irreplaceable world class retail and office destination. LEASING HIGHLIGHTS TRANSIT ORIENTED EXCEPTIONAL DEMOGRAPHICS Steps away from 3rd most active MBTA station, Harvard Square’s One-mile population count of over 58,000, daytime population of Red Line station is the life of the “Brain-Train” 170,000, an average household income in excess of 130,500 and 82% of residents holding a college degree COMPLETE REDEVELOPMENT DOMINANT RETAIL LOCATION Regency Centers is delivering a world-class, fully Over 350 businesses in less than ¼ mile serving 8 million annual gut-renovated building from inside out tourists, 40,000 Harvard University students and employees, and 4.8 million SF of office and lab workers ICONIC PROPERTY EPICENTER OF HARVARD SQUARE One of the most well-known buildings in the Boston area being Prominently sits at the heart of The Square next to Harvard Yard, thoughtfully revitalized by blending historical preservation with Out of Town News, and two MBTA transit stations on both sides modern amenities 99 ® 81 98 THE SQUARE Walk Score Good Transit® Bike Score WALKER’S PARADISE EXCELLENT TRANSIT BIKER’S PARADISE Daily errands do not require a car. Transit is convenient for most trips. Flat as a pancake, excellent bike lanes. BRA TREET TTLE S CHURCH S TREET TREET MA BRATTLE S SSACHUSETT S A MT VENUE . AUBURN S TREET TREET WINTHROP S JFK S MT. -

Office for the Arts and Office of Career Services Announce Inaugural Recipients of Artist Development Fellowships

Office for the Arts and Office of Career Services Announce Inaugural Recipients of Artist Development Fellowships TWELVE UNDERGRADUATE ARTISTS FUNDED TO FURTHER ARTISTIC DEVELOPMENT The Office for the Arts at Harvard (OFA) and Office of Career Services (OCS) are pleased to announce the 2006-07 recipients of the Artist Development Fellowship. This new program supports the artistic development of students demonstrating unusual accomplishment and/or evidence of significant artistic promise. 2007 Artist Development Fellowship Recipients Douglas Balliett ‘07 (Music concentrator, Kirkland House) Professional recording of original musical composition based on Homer’s Odyssey. Assistant principal and principal, double bass for the San Antonio Symphony (2004-present) . Tanglewood Music Center Fellow (summer 2005-06) . Studied composition with John Harbison (2003-04) . Plans to pursue a music career in performance and composition Damien Chazelle ’07-‘08 (VES concentrator, Currier House affiliate) Production of a black-and-white film musical combining the traditions of Hollywood studio era musicals and the French New Wave Cinema. Documentary and musical film credits: Kiwi, Poderistas, I Thought I Heard Him Say, and Mon Père . Internship: Miramax Studios (summer 2004) . Manager and drummer for professional jazz quartet The Rhythm Royales (spring 2001-summer 2003) . Plans to pursue a career in film upon graduation Jane Cheng ’09 (History of Art and Architecture concentrator, Lowell House) Production (design, print and binding) of a fine-press edition of a C.F. Ramuz passage. Cheng plans to submit the project to the National Guild of Bookworkers exhibit in 2008 as well as several other smaller juried exhibits. Articles featured in National Guild of Bookworkers Newsletter (January 2007), and Cincinnati Book Arts Society Newsletter -more- 1 OFA Artist Development Fellowship Recipients, page 2 . -

Neil H. Buchanan

[Updated: June 26, 2017] NEIL H. BUCHANAN The George Washington University Law School 2000 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20052 202-994-3875 [email protected] CURRENT POSITIONS: Professor of Law, The George Washington University, 2011 – present Featured Columnist, Newsweek Opinion, January 2016- present EDUCATION: • Harvard University, A.M. in Economics, Ph.D. in Economics • Monash University, Ph.D. in Laws (with specializations in Public Administration and Taxation) • University of Michigan Law School, J.D. • Vassar College, A.B. in Economics PRIMARY AREAS OF SCHOLARLY AND TEACHING INTEREST: • Intergenerational justice • Government finance and fiscal policy • Tax law • Interdisciplinary approaches to law • Gender and law • Law and economics • Contract law PUBLICATIONS AND WORK IN PROGRESS: Book • THE DEBT CEILING DISASTERS: HOW THE REPUBLICANS CREATED AN UNNECESSARY CONSTITUTIONAL CRISIS AND HOW THE DEMOCRATS CAN FIGHT BACK, Carolina Academic Press (2013) Published Articles and Book Chapters • Social Security is Fair to All Generations: Demystifying the Trust Fund, Solvency, and the Promise to Younger Americans, 27 CORNELL JOURNAL OF LAW & PUBLIC POLICY __ (2017 forthcoming) • Situational Ethics and Veganism (in symposium on Sherry Colb and Michael Dorf, Beating Hearts: Abortion and Animal Rights), BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW ANNEX (Mar. 26, 2017) • Don’t End or Audit the Fed: Central Bank Independence in an Age of Austerity (with Michael C. Dorf), 102 CORNELL LAW REVIEW 1 (2016) • An Odd Remedy That Does Not Solve the Supposed Problem, GEORGE WASHINGTON LAW REVIEW ON THE DOCKET (OCTOBER TERM 2014), 23 May 2015 • Legal Scholarship Makes the World a Better Place, Jotwell – Legal Scholarship We Like and Why It N. -

Seeking a Forgotten History

HARVARD AND SLAVERY Seeking a Forgotten History by Sven Beckert, Katherine Stevens and the students of the Harvard and Slavery Research Seminar HARVARD AND SLAVERY Seeking a Forgotten History by Sven Beckert, Katherine Stevens and the students of the Harvard and Slavery Research Seminar About the Authors Sven Beckert is Laird Bell Professor of history Katherine Stevens is a graduate student in at Harvard University and author of the forth- the History of American Civilization Program coming The Empire of Cotton: A Global History. at Harvard studying the history of the spread of slavery and changes to the environment in the antebellum U.S. South. © 2011 Sven Beckert and Katherine Stevens Cover Image: “Memorial Hall” PHOTOGRAPH BY KARTHIK DONDETI, GRADUATE SCHOOL OF DESIGN, HARVARD UNIVERSITY 2 Harvard & Slavery introducTION n the fall of 2007, four Harvard undergradu- surprising: Harvard presidents who brought slaves ate students came together in a seminar room to live with them on campus, significant endow- Ito solve a local but nonetheless significant ments drawn from the exploitation of slave labor, historical mystery: to research the historical con- Harvard’s administration and most of its faculty nections between Harvard University and slavery. favoring the suppression of public debates on Inspired by Ruth Simmon’s path-breaking work slavery. A quest that began with fears of finding at Brown University, the seminar’s goal was nothing ended with a new question —how was it to gain a better understanding of the history of that the university had failed for so long to engage the institution in which we were learning and with this elephantine aspect of its history? teaching, and to bring closer to home one of the The following pages will summarize some of greatest issues of American history: slavery. -

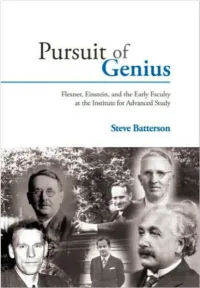

Pursuit of Genius: Flexner, Einstein, and the Early Faculty at the Institute

i i i i PURSUIT OF GENIUS i i i i i i i i PURSUIT OF GENIUS Flexner, Einstein,and the Early Faculty at the Institute for Advanced Study Steve Batterson Emory University A K Peters, Ltd. Natick, Massachusetts i i i i i i i i Editorial, Sales, and Customer Service Office A K Peters, Ltd. 5 Commonwealth Road, Suite 2C Natick, MA 01760 www.akpeters.com Copyright ⃝c 2006 by A K Peters, Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or utilized in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy- ing, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Batterson, Steve, 1950– Pursuit of genius : Flexner, Einstein, and the early faculty at the Institute for Advanced Study / Steve Batterson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 13: 978-1-56881-259-5 (alk. paper) ISBN 10: 1-56881-259-0 (alk. paper) 1. Mathematics–Study and teaching (Higher)–New Jersey–Princeton–History. 2. Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, N.J.). School of Mathematics–History. 3. Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, N.J.). School of Mathematics–Faculty. I Title. QA13.5.N383 I583 2006 510.7’0749652--dc22 2005057416 Cover Photographs: Front cover: Clockwise from upper left: Hermann Weyl (1930s, cour- tesy of Nina Weyl), James Alexander (from the Archives of the Institute for Advanced Study), Marston Morse (photo courtesy of the American Mathematical Society), Albert Einstein (1932, The New York Times), John von Neumann (courtesy of Marina von Neumann Whitman), Oswald Veblen (early 1930s, from the Archives of the Institute for Advanced Study). -

Porcellian Club Centennial, 1791-1891

nia LIBRARY UNIVERSITY W CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO NEW CLUB HOUSE PORCELLIAN CLUB CENTENNIAL 17911891 CAMBRIDGE printed at ttjr itttirnsiac press 1891 PREFATORY THE new building which, at the meeting held in Febru- ary, 1890, it was decided to erect has been completed, and is now occupied by the Club. During the period of con- struction, temporary quarters were secured at 414 Harvard Street. The new building stands upon the site of the old building which the Club had occupied since the year 1833. In order to celebrate in an appropriate manner the comple- tion of the work and the Centennial Anniversary of the Founding of the Porcellian Club, a committee, consisting of the Building Committee and the officers of the Club, was chosen. February 21, 1891, was selected as the date, and it was decided to have the Annual Meeting and certain Literary Exercises commemorative of the occasion precede the Dinner. The Committee has prepared this volume con- taining the Literary Exercises, a brief account of the Din- ner, and a catalogue of the members of the Club to date. A full account of the Annual Meeting and the Dinner may be found in the Club records. The thanks of the Committee and of the Club are due to Brothers Honorary Sargent, Isham, and Chapman for their contribution towards the success of the Exercises Literary ; also to Brother Honorary Hazeltine for his interest in pre- PREFATORY paring the plates for the memorial programme; also to Brother Honorary Painter for revising the Club Catalogue. GEO. B. SHATTUCK, '63, F. R. APPLETON, '75, R. -

Gold Coaster: the Alumni Magazine of Adams House

THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE OF ADAMS HOUSE, HARVARD COLLEGE A T UTOR'S T ALE: W HEN HOUSE IS HOME Sean M. Lynn-Jones The author at the B-entry "Love or Pas de Love" Party in 1992 Choosing (and Being Chosen By) Adams In the spring of 1984, I was a graduate student in the Department of Government at Harvard. For several years, I had aspired to become a resident tutor in one of Harvard’s houses. I hoped that living in a house would provide a sense of community, which was sorely lacking in the lives of most graduate students, not to mention free food and housing. Although I had been a nonresident tutor at Dudley House and then Currier House, I applied to be a resident tutor in Adams, mainly because Jeff Rosen ‘86 told me that Adams might be looking for a Government tutor and encouraged me to apply. At that time, Adams House had a very pronounced image as the “artsy-fartsy gay house.” The stereotype oversimplified the character of the house, but there was no doubt that Adams House was more bohemian, fashionable, tolerant, diverse, and creative than any of Harvard’s other houses, even if it lacked a large population of varsity athletes. My friends joked that I didn’t seem to fit the Adams bill at all: I was straight, my artistic, dramatic, and musical talents were extremely well hidden, and the only black items in my wardrobe were socks. Nevertheless, I convinced myself that tutors didn’t have to fit the stereotype of their houses and enthusiastically applied to Adams, met with Master Robert Kiely and several students, and was pleasantly surprised to receive very soon after an offer of a resident tutorship. -

Harvard and Radcliffe Class of 1964 Fiftieth Reunion May 24–28, 2015

Harvard and Radcliffe Class of 1964 FiftiethHarvard Reunion and Radcliffe Class of 1966 May50th 24–28,Reunion 2015 REGISTRATIONMay 22–26, 2016 GUIDE REGISTRATION GUIDE a CONTENTS CLASS OF 1966 REUNION COMMITTEES Letter to Classmates 3 Reunion Program Reunion Campaign 1636 Society Co-Chairs Tentative 50th Reunion Schedule 4 Committee Co-Chairs Committee Co-Chairs Robert L. Clark Randolph C. Lindel John K. French Penny Hollander Feldman Registration and Donna Gibson Stone Michael F. Holland Financial Assistance 8 C. Kevin Landry* 1636 Society Committee Registration Reunion Program Arthur Patterson Peter M. P. Atkinson Refunds Committee Jeff C. Tarr Katharine Cohen Black Lee H. Allen Thomas E. Black Financial Assistance Thomas E. Black Vice Chair David B. H. Denoon Accommodations 8 Deborah Hill Bornheimer David B. Keidan Benjamin S. Dunham University Housing Frederick J. Corcoran David A. Mittell Jr. Helen Jencks Featherstone Leadership Gift William F. White Room Requests Benjamin Friedman Co-Chairs Sharing a Suite Catherine Boulton Hughes Mitchell L. Adams Campaign Committee Optional Hotel Information Keith L. Hughes Richard Dayle Rippe Role TBD Arrival and Parking Daniel Kleinman Ronald S. Rolfe J. Dinsmore Adams Ellen Robinson Leopold Brian Clemow Rentals John Harvard Roberta Mowry Mundie Rosalind E. Gorin Departure and Checkout Society Chair George Neville Richard E. Gutman Fred M. Lowenfels Packing and Attire 10 Abigail Aldrich Record Stephen E. Myers Gregory P. Pressman Ann Peck Reisen Leadership Gift Attendee Services 10 Sanford J. Ungar Penelope Hedrick Schafer Committee Disabilities and William F. Weld Charles N. Smart John F. DePodesta Certain Medical Conditions David Smith Martin B. Vidgoff Transportation Sanford J. -

MOUNT AUBURN CEMETERY Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-8 OMB No. 1024-0018 MOUNT AUBURN CEMETERY Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Mount Auburn Cemetery Other Name/Site Number: n/a 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Roughly bounded by Mount Auburn Street, Not for publication:_ Coolidge Avenue, Grove Street, the Sand Banks Cemetery, and Cottage Street City/Town: Watertown and Cambridge Vicinityj_ State: Massachusetts Code: MA County: Middlesex Code: 017 Zip Code: 02472 and 02318 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): _ Public-Local: _ District: X Public-State: _ Site: Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object:_ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 4 4 buildings 1 ___ sites 4 structures 15 ___ objects 26 8 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 26 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: n/a NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 MOUNT AUBURN CEMETERY Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

James Russell Lowell - Poems

Classic Poetry Series James Russell Lowell - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive James Russell Lowell(22 February 1819 – 12 August 1891) James Russell Lowell was an American Romantic poet, critic, editor, and diplomat. He is associated with the Fireside Poets, a group of New England writers who were among the first American poets who rivaled the popularity of British poets. These poets usually used conventional forms and meters in their poetry, making them suitable for families entertaining at their fireside. Lowell graduated from Harvard College in 1838, despite his reputation as a troublemaker, and went on to earn a law degree from Harvard Law School. He published his first collection of poetry in 1841 and married Maria White in 1844. He and his wife had several children, though only one survived past childhood. The couple soon became involved in the movement to abolish slavery, with Lowell using poetry to express his anti-slavery views and taking a job in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania as the editor of an abolitionist newspaper. After moving back to Cambridge, Lowell was one of the founders of a journal called The Pioneer, which lasted only three issues. He gained notoriety in 1848 with the publication of A Fable for Critics, a book-length poem satirizing contemporary critics and poets. The same year, he published The Biglow Papers, which increased his fame. He would publish several other poetry collections and essay collections throughout his literary career. Maria White died in 1853, and Lowell accepted a professorship of languages at Harvard in 1854. -

George David Birkhoff and His Mathematical Work

GEORGE DAVID BIRKHOFF AND HIS MATHEMATICAL WORK MARSTON MORSE The writer first saw Birkhoff in the fall of 1914. The graduate stu dents were meeting the professors of mathematics of Harvard in Sever 20. Maxime Bôcher, with his square beard and squarer shoes, was presiding. In the back of the room, with a different beard but equal dignity, William Fogg Osgood was counseling a student. Dun ham Jackson, Gabriel Green, Julian Coolidge and Charles Bouton were in the business of being helpful. The thirty-year-old Birkhoff was in the front row. He seemed tall even when seated, and a friendly smile disarmed a determined face. I had no reason to speak to him, but the impression he made upon me could not be easily forgotten. His change from Princeton University to Harvard in 1912 was de cisive. Although he later had magnificent opportunities to serve as a research professor in institutions other than Harvard he elected to remain in Cambridge for life. He had been an instructor at Wisconsin from 1907 to 1909 and had profited from his contacts with Van Vleck. As a graduate student in Chicago he had known Veblen and he con tinued this friendsip in the halls of Princeton. Starting college in 1902 at the University of Chicago, he changed to Harvard, remained long enough to get an A.B. degree, and then hurried back to Chicago, where he finished his graduate work in 1907. It was in 1908 that he married Margaret Elizabeth Grafius. It was clear that Birkhoff depended from the beginning to the end on her deep understanding and encouragement.