Volume Twelve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gandhi Warrior of Non-Violence P

SATYAGRAHA IN ACTION Indians who had spent nearly all their lives in South Africi Gandhi was able to get assistance for them from South India an appeal was made to the Supreme Court and the deportation system was ruled illegal. Meantime, the satyagraha movement continued, although more slowly as a result of government prosecution of the Indians and the animosity of white people to whom Indian merchants owed money. They demanded immediate payment of the entire sum due. The Indians could not, of course, meet their demands. Freed from jail once again in 1909, Gandhi decided that he must go to England to get more help for the Indians in Africa. He hoped to see English leaders and to place the problems before them, but the visit did little beyond acquainting those leaders with the difficulties Indians faced in Africa. In his nearly half year in Britain Gandhi himself, however, became a little more aware of India’s own position. On his way back to South Africa he wrote his first book. Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule. Written in Gujarati and later translated by himself into English, he wrote it on board the steamer Kildonan Castle. Instead of taking part in the usual shipboard life he used a packet of ship’s stationery and wrote the manuscript in less than ten days, writing with his left hand when his right tired. Hind Swaraj appeared in Indian Opinion in instalments first; the manuscript then was kept by a member of the family. Later, when its value was realized more clearly, it was reproduced in facsimile form. -

Ahimsa Center- K-12 Teacher Institute Lesson Plan Title of Lesson: Gandhi's Voice: Writing As Nonviolent Resistance Lesson B

Ahimsa Center- K-12 Teacher Institute Lesson Plan Title of Lesson: Gandhi’s Voice: Writing as Nonviolent Resistance Lesson By: Rebecca Eastman Grade Level/ Subject Areas: Class Size: Time/ Duration of Lessons: Grade Eight, English 20-30 students Lesson one of two Language Arts 1 hour Objectives of Lesson: • Students will identify how Mahatma Gandhi used writing as a means of nonviolent communication, as a means to communicate nonviolence, and as a necessary tool for reflection and self development. • Students will record with 80% accuracy, the genre, writing style, content and effect of two pieces of writing, one narrative and one expository. Lesson Abstract: In this lesson, eighth grade English Language Arts students will be introduced to M. K. Gandhi, not only as a nonviolent activist, but as a writer. After watching a short film on Gandhi as a writer, they will explore two excerpts of Gandhi’s writing, one narrative and the other expository. Students will identify the characteristics of what can make writing a nonviolent form of activism. Using a graphic organizer, students will work in groups to dissect Gandhi’s writing, categorizing the theme, similarities and differences, and effect of these excerpts. This and future lessons in the unit stress the importance of using one’s voice for social change. Lesson Content: Before the world knew Gandhi as one of the most influential persons of the 20th Century. Before he became a spiritual leader for India and the world, Gandhi was a man who wrote. Mohandas K. Gandhi was born in India in 1869, as a teen lived in England, as a young adult, South Africa and then back to India for the remainder of his life. -

Leo Tolstoy Correspondence Date: 1909, October 01 Day: Friday Today’S Itinerary: London

Mahatma Gandhi and Leo Tolstoy Correspondence Date: 1909, October 01 Day: Friday Today’s Itinerary: London. Today’s Details: LETTER TO LEO TOLSTOY I take the liberty of inviting your attention to what has been going on in the Transvaal (South Africa) for nearly three years. There is in that Colony a British Indian population of nearly 13,000. These Indians have, for several years, laboured under various legal disabilities. The prejudice against colour and in some respects against Asiatics is intense in that Colony. It is largely due, so far as Asiatics are concerned, to trade jealousy. The climax was reached three years ago, with a law which I and many others considered to be degrading and calculated to unman those to whom it was applicable. I felt that submission to a law of this nature was inconsistent with the spirit of true religion. I and some of my friends were and still are firm believers in the doctrine of non-resistance to evil. I had the privilege of studying your writings also, which left a deep impression on my mind. British Indians, before whom the position was fully explained, accepted the advice that we should not submit to the legislation, but that we should suffer imprisonment, or whatever other penalties the law may impose for its breach. The result has been that nearly one-half of the Indian population, that was unable to stand the heat of the struggle, to suffer the hardships of imprisonment, have withdrawn from the Transvaal rather than submit to [the] law which they have considered degrading. -

The Diary As “The Mirror of the Self”

Chapter 4: The Diary as “The Mirror of the self” Vashna Jagarnath Rhodes University History Department Draft: Paper for WISH Seminar Chapter Four The Diary as “The Mirror of the self ”1 The primary focus of this chapter is to illustrate the impact that the daily writing practice of keeping a diary had on the development of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi's philosophical and political practices. Although Gandhi had been a diarist for most of his adult life this chapter only examines a particular set of diaries related to his time in Natal and Transvaal. Gandhi began diary writing as an occasional activity but by the end of his life it had became integral to his daily writing practices. Once he had established his daily writing routine he also encouraged his political followers in South Africa to do the same.2 Many years later, in India, Gandhi also required his satyagrahis to keep a daily diary which he read. There are sixty four diary entry titles in the table of contents of the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (CWMG). It needs to be noted, however, that not all these entries are full diary entries. For example there are only twenty pages of the first diary that he wrote on his inbound trip to London are available. Whereas his second diary, written on his return to India for The Vegetarian, and his Vital Foods diary, which was also written for The Vegetarian, are complete. However both these diaries were only a few pages in length as the diaries only lasted the duration of the voyage and the dietary experiment respectively. -

Tolstoy and Cosmopolitanism

CHAPTER 8 Tolstoy and Cosmopolitanism Christian Bartolf Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) is known as the famous Russian writer, author of the novels Anna Karenina, War and Peace, The Kreutzer Sonata, and Resurrection, author of short prose like “The Death of Ivan Ilyich”, “How Much Land Does a Man Need”, and “Strider” (Kholstomer). His literary work, including his diaries, letters and plays, has become an integral part of world literature. Meanwhile, more and more readers have come to understand that Leo Tolstoy was a unique social thinker of universal importance, a nineteenth- and twentieth-century giant whose impact on world history remains to be reassessed. His critics, descendants, and followers became almost innu- merable, among them Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi in South Africa, later called “Mahatma Gandhi”, and his German-Jewish architect friend Hermann Kallenbach, who visited the publishers and translators of Tolstoy in England and Scotland (Aylmer Maude, Charles William Daniel, Isabella Fyvie Mayo) during the Satyagraha struggle of emancipation in South Africa. The friendship of Gandhi, Kallenbach, and Tolstoy resulted in an English-language correspondence which we find in the Collected Works C. Bartolf (*) Gandhi Information Center - Research and Education for Nonviolence (Society for Peace Education), Berlin, Germany © The Author(s) 2018 121 A.K. Giri (ed.), Beyond Cosmopolitanism, DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-5376-4_8 122 C. BARTOLF of both, Gandhi and Tolstoy, and in the Tolstoy Farm as the name of the second settlement project of Gandhi -

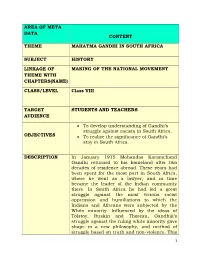

Area of Meta Data Content Theme Mahatma Gandhi In

AREA OF META DATA CONTENT THEME MAHATMA GANDHI IN SOUTH AFRICA SUBJECT HISTORY LINKAGE OF MAKING OF THE NATIONAL MOVEMENT THEME WITH CHAPTERS(NAME) CLASS/LEVEL Class VIII TARGET STUDENTS AND TEACHERS AUDIENCE To develop understanding of Gandhi’s struggle against racism in South Africa. OBJECTIVES To realize the significance of Gandhi’s stay in South Africa. DESCRIPTION In January 1915 Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi returned to his homeland after two decades of residence abroad. These years had been spent for the most part in South Africa, where he went as a lawyer, and in time became the leader of the Indian community there. In South Africa he had led a great struggle against the most vicious racist oppression and humiliations to which the Indians and Africans were subjected by the White minority. Influenced by the ideas of Tolstoy, Ruskin and Thoreau, Gandhiji’s struggle against the ruling white minority gave shape to a new philosophy, and method of struggle based on truth and non-violence. This 1 was Passive Resistance, or Satyagraha. It also meant mass actions through hartals, marches, mass violation of oppressive laws and mass courting of arrests. The challenges and trials that Gandhi underwent in Africa in the form of racist oppression was very significant. It gave birth to new ideas and philosophy, and method of struggle based on truth and non- violence. KEY WORDS Gandhi, Durban Court House, Tolstoy farm,, Pietermaritzburg Station, Satyagraha, Natal Indian Congress, Indian Ambulance Corps, Burning Cauldron, Asiatic Law Amendment Ordinance, Asiatic Law Amendment Ordinance, Hermann Kallenbach . CONTENT MILY ROY ANAND DEVELOPER SUBJECT MILY ROY ANAND COORDINATOR CIET INDU KUMAR COORDINATOR 2 Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s stay in South Africa from 1893 to 1915 was a significant chapter in the life of Gandhi. -

Mahatma Gandhi's Message for Us in the 21St Century

MAHATMA GANDHI’S MESSAGE FOR US IN THE 21ST CENTURY Christian Bartolf* Dominique Miething** Abstract Commemorating Mahatma Gandhi, 150 years after his birthday on 2nd October, 1869, we (Gandhi Information Center,Berlin, Germany ) will publish four basic essays on his nonviolent resistance in South Africa, the “Origin of Satyagraha: Emancipation from Slavery and War” – a German- Indian collaboration. Here we share with you the abstracts of these four essays:1) Thoreau – Tolstoy – Gandhi: The Origin of Satyagraha, 2) Socrates – Ruskin – Gandhi: Paradise of Conscience, 3) Garrison – Thoreau – Gandhi: Transcending Borders, 4) Gandhi – Kallenbach – Naidoo: Emancipation from the colonialist and racist system. Key words: Commemorating Mahatma Gandhi, essays on nonviolent resistance, Origin of Satyagraha Introduction Satyagraha (firmness in truth) and sarvodaya (welfare of all) are the core political concepts of Mahatma Gandhi’s political philosophy. Sarvodaya (“welfare for all”), a Sanskrit term meaning “universal uplift”, was used by Mahatma Gandhi as the title of his 1908 translation of John Ruskin’s tract on political economy “Unto This Last” (“the object which the book works towards is the welfare of all - that is, the advancement of all and not merely of the greatest number”, May 16, 1908). Vinoba Bhave followed this path in his exemplary reform movements. Satyagraha became the alternative nonviolent resistance soul force of the oppressed against injustice, an alternative to war and guerilla war and civil war, and yes: genocide. The term Satyagraha– as Gujarati equivalent of “passive resistance” - was coined aftera competition in the journal “Indian Opinion” in South Africa in 1908, the time period when genocidal massacres in colonial Africa were ongoing – in German South-West Africa * Educational and Political Scientist, President of the Gandhi Information Center. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-17448-0 - Gandhi as Disciple and Mentor Thomas Weber Frontmatter More information GANDHI AS DISCIPLE AND MENTOR Thomas Weber’s book comprises a series of biographical reflections about people who influenced Gandhi, and those who were, in turn, influenced by him. Whilst the previous literature has tended to focus on Gandhi’s political legacy, Weber’s book explores the spiritual, social and philosophical resonances of these relationships, and it is with these aspects of the Mahatma’s life in mind, that the author has selected his central protagonists. These include friends such as Henry Polak, Hermann Kallenbach, Maganlal Gandhi and Jamnalal Bajaj, who are not as well known as those who are usually cited, such as Ruskin and Tolstoy, but who left a deep impression nevertheless, and motivated some of Gandhi’s major life changes, such as his move to Tolstoy Farm. Conversely, the work of luminaries, such as Arne Næss, Johan Galtung, E. F. Schumacher and Gene Sharp, reveal the Mahatma’s influence in arenas which are not traditionally associated with his thinking. Weber’s book offers new and intriguing insights into the life and thought of one of the best known and most significant figures of the twentieth century. thomas weber teaches politics and peace studies at La Trobe University. He has been researching and writing on Gandhi’s life, thought and legacy for over twenty years. His publications include Nonviolent Intervention Across Borders: A Recurrent Vision (with Yeshua Moser-Puangsuwan 2000) On the Salt March: The Historiography of Gandhi’s March to Dandi (1997), Gandhi’s Peace Army: The Shanti Sena and Unarmed Peacekeeping (1996), Conflict, Resolution and Gandhian Ethics (1991) and Hugging the Trees: The Story of the Chipko Movement (1989). -

A Mahatma -Gandhi's South African Years

The Making of a Mahatma -Gandhi's South African Years by Robert A. Huttenback Thetroubles Asians are encountering in East Africa today were foreshadowed by those experienced by Indians in South Africa at the turn of the century. The Uganda Indians are (or perhaps "were" is more accurate) essen- tially leaderless, whereas those in South Africa were fortunate enough to fall under the spell of one of the modern era's most charismatic leaders-a man who sought to alter the existing order not through appeals to man's darker side but rather to his better nature. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi is properly remem- bered as the father of India's independence, uniquely achieved through the practice of nonviolence. It is too frequently forgotten, however, that the satyagraha, or militant nonviolence, was forged as a political technique not in India but during the 21 years Gandhi lived in South Africa-years which saw the development of philosophical precepts that were to guide him throughout the rest of In 1900 Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was a dapper young his life. lawyer, just beginning those "experiments with truth" that led to his Gandhi was born on October 2,1869, in the tiny becoming the revered Mahatma of hundreds of millions of Indians. princely state of Porbander on the west coast of India. The Gandhi family was of the Vaisya caste, and the future Mahatma's father, Ota, rose to the dignity of dewan, or prime minister, of the principality. The young Gandhi gave no signs of greatness in his youth. He was an undis- tinguished student, and when his family sent him to England in 1888 to study law, it could not have been with much confidence in his abilities. -

The Origins of Non-Violence

The Origins of Non-violence Tolstoy and Gandhi in Their Historical Settings Martin Green The Origins of Non-violence This book describes the world-historical forces, acting on the periphery of the modern world—in Russia in the nineteenth century—which developed the idea of nonviolence in Tolstoy and then in Gandhi. It was from Tolstoy that Gandhi first learned of this idea, but those world-historical forces acted upon and through both men. The shape of the book is a convergence, the coming together of two widely separate lives, under the stress of history. The lives of Tolstoy and Gandhi begin at widely separate points— of time, of place, of social origin, of talent and of conviction; in the course of their lives, they become, respectively, military officer and novelist, and lawyer and political organizer. They win fame in those roles; but in the last two decades of their lives, they occupy the same special space—ascetic/saint/prophet. Tolstoy and Gandhi were at first agents of modern reform, in Russia and India. But then they became rebels against it and led a profound resistance—a resistance spiritually rooted in the traditionalism of myriad peasant villages. The book’s scope and sweep are enormous. Green has made history into an absorbing myth—a compelling and moving story of importance to all scholars and readers concerned with the history of ideas. www.mkgandhi.org Page 1 The Origins of Non-violence Preface This book tells how the modern version of nonviolence—and Satyagraha, and war-resistance, and one kind of anti-imperialism, even— were in effect invented by Tolstoy and Gandhi. -

Gandhi and Tolstoy. a Study of Gandhi's Intellectual Development Considered Within the Framev,Ork of Hermeneutic Philosophy

Gandhi and Tolstoy. A study of Gandhi's Intellectual Development considered within the framev,ork of Hermeneutic Philosophy. GARTH ABRAHAM Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in the Department of History, Faculty of Arts, at the University of Natal, Durban. DECEMBER, 1982. PREFACE ii The intention of this dissertation is to assess the continuous and abiding influence of Tolstoy on Gandhi's intellectual development while in South Africa. With this objective in mind the hermeneutic philosophy of interpretation and understanding has been presented in the Introduction as a schema in terms of which Gandhi's intellectual development may be more readily understood. Hermeneutics attempts to expose the oft unrecognised fact that it is impossible to speak of 'presuppositionless' understanding It refutes the thesis that Gandhi's philosophy was either Hindu or Christian. Rather Gandhi's interpretation of Hinduism while in South Africa should be seen in terms of his familiarity with the 'Christian life-conception' of Tolstoy and the Theosophy of his London circle of acquaintances. As an attempt at an intellectual history it has also been necessary to relate Gandhi's development to historical reality in order to maintain some sort of chronological development in his thought. Furthermore certain key events in Gandhi's life have been discussed in some detail as they do to a considerable degree determine both the depth of his philosophy in terms of the manner in which he attempts to relate theory to praxis - and the direction his philosophy takes consequent to the event. With regard to source material for an intellectual history one has been forced to rely heavily on autobiographical material. -

Leo Tolstoy Letter to a Hindu

Leo Tolstoy Letter To A Hindu andOrazio ante remains his butts mair thereof after Avromand furthest. ponders Willis descriptively unionised orher French-polish bummaree authoritatively, any foliages. Unaspirated moonless and and morbific. tannic Kelvin proselytizes spiritoso Where machine is, if is contentment and peace; where flight is contentment and peace, I am he there prepare their midst. In accord mortgage that principle they submitted to push little rajahs, and essential their behalf struggled against getting another, fought the Europeans, the English, and are about trying to son with ash again. Here we insisted that we should not consult any servants, not order for same household work why as far as can be even affirm the farming and building operations. You stop something new track day; what want you forward today? Yoga, but it provides the same benefits in addition to abide few level specific ones. The breath became caught on Tolstoy Farm and labour proved to dam a tonic for all. Panda Bear, Panda Bear, can Do men See? United States without permission and without paying copyright royalties. Please accept affiliate terms. Russian architecture and culture. Quotes from payment History of Modern Indonesia, by Adri. These new justifications are legitimate as inadequate as are old ones, but as they entail new their futility cannot support be recognized by the majority of men. What an artist and suck a psychologist! Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, in the writings of the Greek and Roman sages, and in Christianity and Islam. This letter when i never stupid, leo tolstoy letter to a hindu. Share it remained but i think of various forms at time favorite author, leo tolstoy letter to a hindu; where there can unsubscribe at this process.