Arthur Smith Woodward's Legacy to Geology In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annotated Checklist of Fossil Fishes from the Smoky Hill Chalk of the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) in Kansas

Lucas, S. G. and Sullivan, R.M., eds., 2006, Late Cretaceous vertebrates from the Western Interior. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 35. 193 ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF FOSSIL FISHES FROM THE SMOKY HILL CHALK OF THE NIOBRARA CHALK (UPPER CRETACEOUS) IN KANSAS KENSHU SHIMADA1 AND CHRISTOPHER FIELITZ2 1Environmental Science Program and Department of Biological Sciences, DePaul University,2325 North Clifton Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60614; and Sternberg Museum of Natural History, Fort Hays State University, 3000 Sternberg Drive, Hays, Kansas 67601;2Department of Biology, Emory & Henry College, P.O. Box 947, Emory, Virginia 24327 Abstract—The Smoky Hill Chalk Member of the Niobrara Chalk is an Upper Cretaceous marine deposit found in Kansas and adjacent states in North America. The rock, which was formed under the Western Interior Sea, has a long history of yielding spectacular fossil marine vertebrates, including fishes. Here, we present an annotated taxo- nomic list of fossil fishes (= non-tetrapod vertebrates) described from the Smoky Hill Chalk based on published records. Our study shows that there are a total of 643 referable paleoichthyological specimens from the Smoky Hill Chalk documented in literature of which 133 belong to chondrichthyans and 510 to osteichthyans. These 643 specimens support the occurrence of a minimum of 70 species, comprising at least 16 chondrichthyans and 54 osteichthyans. Of these 70 species, 44 are represented by type specimens from the Smoky Hill Chalk. However, it must be noted that the fossil record of Niobrara fishes shows evidence of preservation, collecting, and research biases, and that the paleofauna is a time-averaged assemblage over five million years of chalk deposition. -

Memoirs of the National Museum, Melbourne January 1906

Memoirs of the National Museum, Melbourne January 1906 https://doi.org/10.24199/j.mmv.1906.1.01 ON A CARBONIFEROUS FISH-FAUNA FROM THE MANSFIELD DISTRICT, VICTORIA. f BY AWL'HUR SJnTu T oomYARD, LL.D., F.U..S. I.-IN'l1RODUC'I1ION. The fossil fish-remains colloctocl by 1fr. George Sweet, F.G.S., from the reel rncks of the Mansfield District, are in a very imperfect state of presern1tion. 'J1lic·y vary considerably in appea1·a11co according to the Hature of the stratum whence they were obtained. 'l'he specimens in the harder ealcm-oous layers retain their original bony ot· ealcifiocl tissue, which ndhores to tbe rock ancl cannot readily ho exposed without fractnre. 'l'he remains hnriecl in the more fcrruginous ancl sanely layers have left only hollmv moulds of their outm1rd shape, or arc much doeayod and thus Yeq difficult to recognise. MoreQvor, the larger fishes arc repr0sontNl only hy senttcrocl fragments, while the smaller fishes, eYon when approximately whole, arc more or less distorted and disintcgrato(l. Under these circumstancPs, with few materials for comparison, it is not Rnrprising that the latt: Sil' Broderick McCoy should haYe failed to pnbJii.,h a sntisfactory a(•eount of the Mansfield eollection. \Yith great skill, ho sPlcctcd nearly all the more important specimens to be drawn in the series of plates accom panying the present memoir. II0 also instructed ancl snp0rvif-ecl the artist, so thnt moRt of' tbc pl'ineipnl foaturcs of the fossils "\Yore duly 0111phasisc•cl. IIis preliminary determinations, however, published in 1800, 1 arc now shown to have been for the most part erroneous; while his main conelusions as to the affinities of 1 F. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-17944-8 — Evolution And

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-17944-8 — Evolution and Development of Fishes Edited by Zerina Johanson , Charlie Underwood , Martha Richter Index More Information Index abaxial muscle,33 Alizarin red, 110 arandaspids, 5, 61–62 abdominal muscles, 212 Alizarin red S whole mount staining, 127 Arandaspis, 5, 61, 69, 147 ability to repair fractures, 129 Allenypterus, 253 arcocentra, 192 Acanthodes, 14, 79, 83, 89–90, 104, 105–107, allometric growth, 129 Arctic char, 130 123, 152, 152, 156, 213, 221, 226 alveolar bone, 134 arcualia, 4, 49, 115, 146, 191, 206 Acanthodians, 3, 7, 13–15, 18, 23, 29, 63–65, Alx, 36, 47 areolar calcification, 114 68–69, 75, 79, 82, 84, 87–89, 91, 99, 102, Amdeh Formation, 61 areolar cartilage, 192 104–106, 114, 123, 148–149, 152–153, ameloblasts, 134 areolar mineralisation, 113 156, 160, 189, 192, 195, 198–199, 207, Amia, 154, 185, 190, 193, 258 Areyongalepis,7,64–65 213, 217–218, 220 ammocoete, 30, 40, 51, 56–57, 176, 206, 208, Argentina, 60–61, 67 Acanthodiformes, 14, 68 218 armoured agnathans, 150 Acanthodii, 152 amphiaspids, 5, 27 Arthrodira, 12, 24, 26, 28, 74, 82–84, 86, 194, Acanthomorpha, 20 amphibians, 1, 20, 150, 172, 180–182, 245, 248, 209, 222 Acanthostega, 22, 155–156, 255–258, 260 255–256 arthrodires, 7, 11–13, 22, 28, 71–72, 74–75, Acanthothoraci, 24, 74, 83 amphioxus, 49, 54–55, 124, 145, 155, 157, 159, 80–84, 152, 192, 207, 209, 212–213, 215, Acanthothoracida, 11 206, 224, 243–244, 249–250 219–220 acanthothoracids, 7, 12, 74, 81–82, 211, 215, Amphioxus, 120 Ascl,36 219 Amphystylic, 148 Asiaceratodus,21 -

Equisetalean Plant Remains from the Early to Middle Triassic of New South Wales, Australia

Records of the Australian Museum (2001) Vol. 53: 9–20. ISSN 0067-1975 Equisetalean Plant Remains from the Early to Middle Triassic of New South Wales, Australia W.B. KEITH HOLMES “Noonee Nyrang”, Gulgong Road, Wellington NSW 2820, Australia Honorary Research Fellow, Geology Department, University of New England, Armidale NSW 2351, Australia [email protected] Present address: National Botanical Institute, Private Bag X101, Pretoria, 0001, South Africa ABSTRACT. Equisetalean fossil plant remains of Early to Middle Triassic age from New South Wales are described. Robust and persistent nodal diaphragms composed of three zones; a broad central pith disc, a vascular cylinder and a cortical region surrounded by a sheath of conjoined leaf bases, are placed in Nododendron benolongensis n.sp. The new genus Townroviamites is erected for stems previously assigned to Phyllotheca brookvalensis which bear whorls of leaves forming a narrow basal sheath and the number of leaves matches the number of vascular bundles. Finely striated stems bearing leaf whorls consisting of several foliar lobes each formed from four to seven linear conjoined leaves are described as Paraschizoneura jonesii n.sp. Doubts are raised about the presence of the common Permian Gondwanan sphenophyte species Phyllotheca australis and the Northern Hemisphere genus Neocalamites in Middle Triassic floras of Gondwana. HOLMES, W.B. KEITH, 2001. Equisetalean plant remains from the Early to Middle Triassic of New South Wales, Australia. Records of the Australian Museum 53(1): 9–20. The plant Phylum Sphenophyta, which includes the Permian Period, the increasing aridity and decline in the equisetaleans, commonly known as “horse-tails” or vegetation of northern Pangaea was in contrast to that in “scouring rushes”, first appeared during the Devonian southern Pangaea—Gondwana—where flourishing swamp Period (Taylor & Taylor, 1993). -

Ichthyodectiform Fishes from the Late Cretaceous

Mesozoic Fishes 5 – Global Diversity and Evolution, G. Arratia, H.-P. Schultze & M. V. H. Wilson (eds.): pp. 247-266, 12 figs., 2 tabs. © 2013 by Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, München, Germany – ISBN 978-3-89937-159-8 Ichthyodectiform fi shes from the Late Cretaceous (Campanian) of Arkansas, USA Kelly J. IRWIN and Christopher FIELITZ Abstract Several specimens of the ichthyodectiform fishes Xiphactinus audax and Saurocephalus cf. S. lanciformis are reported from the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) Brownstown Marl and Ozan formations of southwestern Arkansas, U.S.A. Seven individuals of Xiphactinus, based on incomplete specimens, are represented by various elements: disarticu- lated skull bones, jaw fragments, pectoral fin-rays, or vertebrae. The circular vertebral centra are diagnostic for X. audax rather than X. vetus. The specimen of Saurocephalus consists of a three-dimensional skull, lacking much of the skull roof bones. It is identified as Saurocephalus based on the shape of the predentary bone. This specimen provides the first record of entopterygoid teeth in Saurocephalus. These specimens represent new geographic and geologic distribution records of these taxa from the western Gulf Coastal Plain, which biogeographically links records from the eastern Gulf Coastal Plain with those from the Western Interior Sea. Introduction LEIDY (1854) was the first to report the presence of Cretaceous marine vertebrate fossils from Arkansas, yet in the intervening 150+ years, the body of work on the paleoichthyofauna of Arkansas remains limited (WILSON & BRUNER 2004). BARDACK (1965), GOODY (1976), CASE (1978), and RUSSELL (1988) re- ported geographic and geologic distributions for specific taxa, but few descriptive works on fossil fishes are available (see HUSSAKOF 1947; MEYER 1974; BECKER et al. -

Background Paper on New South Wales Geology with a Focus on Basins Containing Coal Seam Gas Resources

Background Paper on New South Wales Geology With a Focus on Basins Containing Coal Seam Gas Resources for Office of the NSW Chief Scientist and Engineer by Colin R. Ward and Bryce F.J. Kelly School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences University of New South Wales Date of Issue: 28 August 2013 Our Reference: J083550 CONTENTS Page 1. AIMS OF THE BACKGROUND PAPER .............................................................. 1 1.1. SIGNIFICANCE OF AUSTRALIAN CSG RESOURCES AND PRODUCTION ................... 1 1.2. DISCLOSURE .................................................................................................... 2 2. GEOLOGY AND EVALUATION OF COAL AND COAL SEAM GAS RESOURCES ............................................................................................................. 3 2.1. NATURE AND ORIGIN OF COAL ........................................................................... 3 2.2. CHEMICAL AND PHYSICAL PROPERTIES OF COAL ................................................ 4 2.3. PETROGRAPHIC PROPERTIES OF COAL ............................................................... 4 2.4. GEOLOGICAL FEATURES OF COAL SEAMS .......................................................... 6 2.5. NATURE AND ORIGIN OF GAS IN COAL SEAMS .................................................... 8 2.6. GAS CONTENT DETERMINATION ........................................................................10 2.7. SORPTION ISOTHERMS AND GAS HOLDING CAPACITY .........................................11 2.8. METHANE SATURATION ....................................................................................12 -

FEBRUARY 5Th, 1875

206 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING. FEBRUARY 5th, 1875. ROBERT ETHERIDGE, Esq., F.R.S., F.G.S., &c., Vice-President, in the Chair. The following Report was read by the Honorary Secretary :- REPORT OF THE GENERAL COMMITTEE FOR 1874. The General Committee have much pleasure in congratulating the Association upon the results of the past year. A considerable number of new Members have been added to the list, and several of these are already well known throughout the country, by their study and practice of Geological Science. There have been a few losses by death, and, if the number of those who have retired is somewhat more numerous than has been the case of later years, they consisted, with few exceptions, of Members whose interest in the proceedings of the Association was never very ardent. Members elected during 1874 49 Withdrawals 14, Deaths 4 . 18 Increase 31 The Census of the Association on the 1st January, 1875, gave the following results :- Honorary Members 12 Life Members. 42 Old Country Members 28 Other Members 257 339 The lamented death of Professor Phillips, reduces the number of Honorary Members to 12. A short notice of the sad occurrence, which deprived the Association of one amongst the most eminent 206 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING. of its body, will be found in the forthcoming number of Vol. iv. of the" Proceedings." The financial position of the Association is very satisfactory, and the large number of Members now contributing has yielded a sum which amply provides for an increased expenditure, the benefits of which are shared by all. -

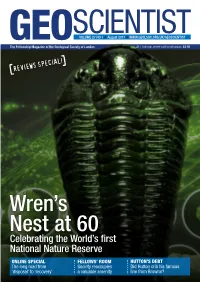

Wren's Nest at 60

SCIENTISTVOLUME 27 NO 7 ◆ August 2017 ◆ WWW.GEOLSOC.ORG.UK/GEOSCIENTIST GEOThe Fellowship Magazine of the Geological Society of London UK / Overseas where sold to individuals: £3.95 ] [REVIEWS SPECIAL! Wren’s Nest at 60 Celebrating the World’s first National Nature Reserve ONLINE SPECIAL FELLOWS’ ROOM HUTTON’S DEBT The long road from Society reoccupies Did Hutton crib his famous ‘disposal’ to ‘recovery’ a valuable amenity line from Browne? GEOSCIENTIST CONTENTS 17 24 10 25 REGULARS IN THIS ISSUE... 05 Welcome Ted Nield says true ‘scientific outreach’ is integral, not a strap-on prosthetic. 06 Society News What your Society is doing at home and abroad, in London and the regions. 09 Soapbox Mike Leeder discusses Hutton’s possible debt to Sir Thomas Browne ON THE COVER: 16 Calendar Society activities this month 10 CATCHING THE DUDLEY BUG 20 Letters New The state of Geophysics MSc courses in the Andrew Harrison looks back on the UK; The new CPD system (continued). 61st year of the World’s first NNR 22 Books and arts Thirteen new books reviewed by Dawn Brooks, Malcolm Hart, Gordon Neighbour, Calymene blumenbachii or ‘Dudley Bug’. James Montgomery, Wendy Cawthorne, Jeremy Joseph, David Nowell, Martin Brook, Alan Golding, Mark Griffin, Courtesy, Dudley Museum Services Hugh Torrens, Nina Morgan and Amy-Jo Miles 24 People Geoscientists in the news and on the move 27 Obituary Robin Temple Hazell 1927 - 2017 RECOVERY V. DISPOSAL William Braham 1957 -2016 NLINE Chris Berryman on applying new guidance 27 Obituary affecting re-use of waste soil materials. -

James Hutton's Reputation Among Geologists in the Late Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

The Geological Society of America Memoir 216 Revising the Revisions: James Hutton’s Reputation among Geologists in the Late Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries A. M. Celâl Şengör* İTÜ Avrasya Yerbilimleri Enstitüsü ve Maden Fakültesi, Jeoloji Bölümü, Ayazağa 34469 İstanbul, Turkey ABSTRACT A recent fad in the historiography of geology is to consider the Scottish polymath James Hutton’s Theory of the Earth the last of the “theories of the earth” genre of publications that had begun developing in the seventeenth century and to regard it as something behind the times already in the late eighteenth century and which was subsequently remembered only because some later geologists, particularly Hutton’s countryman Sir Archibald Geikie, found it convenient to represent it as a precursor of the prevailing opinions of the day. By contrast, the available documentation, pub- lished and unpublished, shows that Hutton’s theory was considered as something completely new by his contemporaries, very different from anything that preceded it, whether they agreed with him or not, and that it was widely discussed both in his own country and abroad—from St. Petersburg through Europe to New York. By the end of the third decade in the nineteenth century, many very respectable geologists began seeing in him “the father of modern geology” even before Sir Archibald was born (in 1835). Before long, even popular books on geology and general encyclopedias began spreading the same conviction. A review of the geological literature of the late eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries shows that Hutton was not only remembered, but his ideas were in fact considered part of the current science and discussed accord- ingly. -

Copyrighted Material

06_250317 part1-3.qxd 12/13/05 7:32 PM Page 15 Phylum Chordata Chordates are placed in the superphylum Deuterostomia. The possible rela- tionships of the chordates and deuterostomes to other metazoans are dis- cussed in Halanych (2004). He restricts the taxon of deuterostomes to the chordates and their proposed immediate sister group, a taxon comprising the hemichordates, echinoderms, and the wormlike Xenoturbella. The phylum Chordata has been used by most recent workers to encompass members of the subphyla Urochordata (tunicates or sea-squirts), Cephalochordata (lancelets), and Craniata (fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals). The Cephalochordata and Craniata form a mono- phyletic group (e.g., Cameron et al., 2000; Halanych, 2004). Much disagree- ment exists concerning the interrelationships and classification of the Chordata, and the inclusion of the urochordates as sister to the cephalochor- dates and craniates is not as broadly held as the sister-group relationship of cephalochordates and craniates (Halanych, 2004). Many excitingCOPYRIGHTED fossil finds in recent years MATERIAL reveal what the first fishes may have looked like, and these finds push the fossil record of fishes back into the early Cambrian, far further back than previously known. There is still much difference of opinion on the phylogenetic position of these new Cambrian species, and many new discoveries and changes in early fish systematics may be expected over the next decade. As noted by Halanych (2004), D.-G. (D.) Shu and collaborators have discovered fossil ascidians (e.g., Cheungkongella), cephalochordate-like yunnanozoans (Haikouella and Yunnanozoon), and jaw- less craniates (Myllokunmingia, and its junior synonym Haikouichthys) over the 15 06_250317 part1-3.qxd 12/13/05 7:32 PM Page 16 16 Fishes of the World last few years that push the origins of these three major taxa at least into the Lower Cambrian (approximately 530–540 million years ago). -

Histoire(S) De Collecfions

Colligo Histoire(s) de Collections Colligo 3 (3) Hors-série n°2 2020 PALÉONTOLOGIE How to build a palaeontological collection: expeditions, excavations, exchanges. Paleontological collections in the making – an introduction to the special issue Irina PODGORNY, Éric BUFFETAUT & Maria Margaret LOPES P. 3-5 La guerre, la paix et la querelle. Les sociétés A Frenchman in Patagonia: the palaeontological paléontologiques d'Auvergne sous la Seconde expeditions of André Tournouër (1898-1903) Restauration Irina PODGORNY Éric BUFFETAUT P. 7-31 P. 67-80 Two South American palaeontological collections Paul Carié, Mauritian naturalist and forgotten in the Natural History Museum of Denmark collector of dodo bones Kasper Lykke HANSEN Delphine ANGST & Éric BUFFETAUT P. 33-44 P. 81-88 Cataloguing the Fauna of Deep Time: Researchers following the Glossopteris trail: social Paleontological Collections in Brazil in the context of the debate surrounding the continental Beginning of the 20th Century drift theory in Argentina in the early 20th century Maria Margaret LOPES Mariana F. WALIGORA P. 45-56 P. 89-103 The South American Mammal collection at the Natural history collecting by the Navy in French Museo Geologico Giovanni Capellini (Bologna, Indochina Italy) Virginia VANNI et al. Marie-Béatrice FOREL P. 57-66 P. 105-126 1 SOMMAIRE Paleontological collections in the making – an introduction to the special issue Collections paléontologiques en développement – introduction au numéro spécial Irina PODGORNY, Éric BUFFETAUT & Maria Margaret LOPES P. 3-5 La guerre, la paix et la querelle. Les sociétés paléontologiques d'Auvergne sous la Seconde Restauration War, Peace, and Quarrels: The paleontological Societies in Auvergne during the Second Bourbon Restoration Irina PODGORNY P. -

Body Fossils and Root-Penetration Structures

CHAPTER 16 BODY FOSSILS AND ROOT-PENETRATION STRUCTURES 482 BODY FOSSILS AND ROOT-PENETRATION STRUCTURES RECORDED FROM THE STUDY AREA 16.1. INTRODUCTION There are three major groups of body fossils that occur in the Triassic rocks of the study area, including the Hawkesbury Sandstone. The first group comprises fossil plant remains, which are abundant and previously well studied (e.g. Helby, 1969a,b & 1973; Retallack, 1976, 1977a, b, c, & 1980), and root-penetration structures. The second group comprises fossil animal remains which are extremely rare and, except for locally abundant fossil freshwater fish in shale lenses in the Hawkesbury Sandstone and the Gosford (=Terrigal) Formation (see Reggatt, in Packham 1969, P.407; and Branagan, in Packham 1969, p.415-416), include the bones of amphibians (e.g. Warren, 1972 & 1983; and Beale, 1985) and bivalve mollusc shells of mytilid affinity (Grant-Mackie et al., 1985). Additionally, the freshwater fossil pelecypod, Unio, the branchiopod Estheria, and a variety of insects have been recorded from the Hawkesbury Sandstone (cf. Branagan, in Packham 1969, p.417). The third group comprises microfossils (microfauna and microflora) (e.g. Helby, in Packham, 1969 p.404-405 and 417; Retallack, 1980; Grant-Mackie et al., 1985). The abundance of spores, megaspores, intact spore tetrads, and abundant quantities of other microscopic organic materials including acritarchs (possibility having been reworked) have been suggested as evi dence that the palaeoenvironment of the Newport Formation was as marginal marine, possibly of lagoonal or estuarine character (Grant-Mackie et al., 1985). 483 16.2. TAXONOMY OF THE PLANT REMAINS AND ROOT-PENETRATION STRUCTURES 16.2.1.