An Annotated Select Bibliography of the Piltdown Forgery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lost World Study Pack

The Lost World Study Pack 1 Contents … 1.0. Introduction ………………………………………………………………………….. 3 2.0. Dinosaurs in Popular Culture ……………………………………………….4-8 2.1. Timeline of relevant scientific and cultural event surrounding the publication of the lost world………………….. 6 2.2. Quiz…………………………………………………………………………. 7-8 3.0. The Lost World in Context …………………………………………..…….9-12 3.1. Christianity ……………………………………………………….……9-11 3.2. British Colonialism ………………………………………………11-12 4.0. The Real Lost World ………………………………………………………..13-16 5.0. The Ape Men …………………………………………………………………..17-22 5.1. Crossword ……………………………………………………………….. 21 5.2. Family tree ………………………………………………………………. 22 6.0. The Mystery of the Piltdown Man ………………………………….. 23-29 2 Introduction ‘The Lost World’ is a highly influential science fiction novel written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and published in 1912. The story is one which suspends the ordinary laws of nature and submerges you, instead, in a prehistoric landscape, hidden deep within the South American rainforest where the great dinosaurs of the past continue to survive – claws and all. The novel follows the exploration of the notoriously outspoken Professor Challenger, a young reporter Edward Malone, Challenger’s professional rival Professor Summerly, and the classic adventurer Lord John Roxton as they struggle for survival faced with a catalogue of dangerous and … extinct species. Since its publication, ‘The Lost World’ has proven to be one of Doyle’s most influential works, well and truly establishing dinosaurs in the public imagination and inspiring a great deal of successive science fiction. To create this novel, Doyle drew inspiration from a wide range of sources, including earlier science fiction, historic travel accounts, fossil finds near his own home, and the catalytic theories of evolution and palaeontology. -

PATHOLOGICAL CRANIAL LESIONS in a JUVENILE CRANIAL COLLECTION a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of San Francisco State Universit

PATHOLOGICAL CRANIAL LESIONS IN A JUVENILE CRANIAL COLLECTION A Thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University in partial fulfillment of A - the Requirements for -i r the degree M2 Master of Arts In . IsA 53 Anthropology by Hannah Marie Miller San Francisco, California January 2018 Copyright By Hannah Marie Miller 2018 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Pathological Cranial Lesions in a Juvenile Cranial Collection by Hannah Marie Miller, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requests for the degree: Master of Arts in Anthropology at San Francisco State University. Cymhia Wilczak Associate Professor of Anthropology Associate Professor of Anthropology PATHOLOGICAL CRANIAL LESIONS IN A JUVENILE CRANIAL COLLECTION Hannah Marie Miller San Francisco, California 2018 The purpose of this study is to examine and analyze the age distributions and co-occurrence of endocranial and ectocranial lesions commonly associated with metabolic disease and inflammatory processes in juveniles. The pathogenic changes studied are porotic hyperostosis, cribra orbitalia and endocranial lesions. The specific etiology of any of these lesions remains uncertain. (Lewis 2004, Janovic et al. 2012, Walker et al. 2009, Wilczak and Zimova Hopkins 2010). While porotic hyperostosis and cribra orbitalia have been subject to multiple studies, to date no one has statistically confirmed a relationship between these lesions. Endocranial lesions have never been systematically studied in conjunction with porotic hyperostosis or cribra orbitalia. As Wilczak and Zimova Hopkins (2010) suggested that not all lesions classified as cribra orbitalia shared a common etiology, classification of porotic hyperostosis and cribra orbitalia were modified for analysis here. -

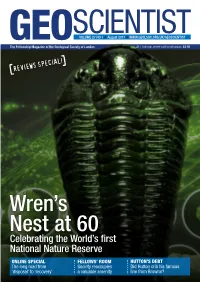

Wren's Nest at 60

SCIENTISTVOLUME 27 NO 7 ◆ August 2017 ◆ WWW.GEOLSOC.ORG.UK/GEOSCIENTIST GEOThe Fellowship Magazine of the Geological Society of London UK / Overseas where sold to individuals: £3.95 ] [REVIEWS SPECIAL! Wren’s Nest at 60 Celebrating the World’s first National Nature Reserve ONLINE SPECIAL FELLOWS’ ROOM HUTTON’S DEBT The long road from Society reoccupies Did Hutton crib his famous ‘disposal’ to ‘recovery’ a valuable amenity line from Browne? GEOSCIENTIST CONTENTS 17 24 10 25 REGULARS IN THIS ISSUE... 05 Welcome Ted Nield says true ‘scientific outreach’ is integral, not a strap-on prosthetic. 06 Society News What your Society is doing at home and abroad, in London and the regions. 09 Soapbox Mike Leeder discusses Hutton’s possible debt to Sir Thomas Browne ON THE COVER: 16 Calendar Society activities this month 10 CATCHING THE DUDLEY BUG 20 Letters New The state of Geophysics MSc courses in the Andrew Harrison looks back on the UK; The new CPD system (continued). 61st year of the World’s first NNR 22 Books and arts Thirteen new books reviewed by Dawn Brooks, Malcolm Hart, Gordon Neighbour, Calymene blumenbachii or ‘Dudley Bug’. James Montgomery, Wendy Cawthorne, Jeremy Joseph, David Nowell, Martin Brook, Alan Golding, Mark Griffin, Courtesy, Dudley Museum Services Hugh Torrens, Nina Morgan and Amy-Jo Miles 24 People Geoscientists in the news and on the move 27 Obituary Robin Temple Hazell 1927 - 2017 RECOVERY V. DISPOSAL William Braham 1957 -2016 NLINE Chris Berryman on applying new guidance 27 Obituary affecting re-use of waste soil materials. -

Resolving Homology in the Face of Shifting Germ Layer Origins

REVIEW ARTICLE Resolving homology in the face of shifting germ layer origins: Lessons from a major skull vault boundary Camilla S Teng1,2†, Lionel Cavin3, Robert E Maxson Jnr2, Marcelo R Sa´ nchez-Villagra4, J Gage Crump1* 1Department of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, United States; 2Department of Biochemistry, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, United States; 3Department of Earth Sciences, Natural History Museum of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland; 4Paleontological Institute and Museum, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland Abstract The vertebrate skull varies widely in shape, accommodating diverse strategies of feeding and predation. The braincase is composed of several flat bones that meet at flexible joints called sutures. Nearly all vertebrates have a prominent ‘coronal’ suture that separates the front and back of the skull. This suture can develop entirely within mesoderm-derived tissue, neural crest- derived tissue, or at the boundary of the two. Recent paleontological findings and genetic insights in non-mammalian model organisms serve to revise fundamental knowledge on the development and evolution of this suture. Growing evidence supports a decoupling of the germ layer origins of *For correspondence: the mesenchyme that forms the calvarial bones from inductive signaling that establishes discrete [email protected] bone centers. Changes in these relationships facilitate skull evolution and may create susceptibility to disease. These concepts provide a general framework for approaching issues of homology in Present address: †Department of Cell and Tissue Biology, cases where germ layer origins have shifted during evolution. University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, United States Introduction Competing interests: The At the beginning of skull vault development, mesenchymal cells of either neural crest or mesoderm authors declare that no origin condense into nascent bone fields. -

Histoire(S) De Collecfions

Colligo Histoire(s) de Collections Colligo 3 (3) Hors-série n°2 2020 PALÉONTOLOGIE How to build a palaeontological collection: expeditions, excavations, exchanges. Paleontological collections in the making – an introduction to the special issue Irina PODGORNY, Éric BUFFETAUT & Maria Margaret LOPES P. 3-5 La guerre, la paix et la querelle. Les sociétés A Frenchman in Patagonia: the palaeontological paléontologiques d'Auvergne sous la Seconde expeditions of André Tournouër (1898-1903) Restauration Irina PODGORNY Éric BUFFETAUT P. 7-31 P. 67-80 Two South American palaeontological collections Paul Carié, Mauritian naturalist and forgotten in the Natural History Museum of Denmark collector of dodo bones Kasper Lykke HANSEN Delphine ANGST & Éric BUFFETAUT P. 33-44 P. 81-88 Cataloguing the Fauna of Deep Time: Researchers following the Glossopteris trail: social Paleontological Collections in Brazil in the context of the debate surrounding the continental Beginning of the 20th Century drift theory in Argentina in the early 20th century Maria Margaret LOPES Mariana F. WALIGORA P. 45-56 P. 89-103 The South American Mammal collection at the Natural history collecting by the Navy in French Museo Geologico Giovanni Capellini (Bologna, Indochina Italy) Virginia VANNI et al. Marie-Béatrice FOREL P. 57-66 P. 105-126 1 SOMMAIRE Paleontological collections in the making – an introduction to the special issue Collections paléontologiques en développement – introduction au numéro spécial Irina PODGORNY, Éric BUFFETAUT & Maria Margaret LOPES P. 3-5 La guerre, la paix et la querelle. Les sociétés paléontologiques d'Auvergne sous la Seconde Restauration War, Peace, and Quarrels: The paleontological Societies in Auvergne during the Second Bourbon Restoration Irina PODGORNY P. -

V Semester Zoology Fossils and Fossil Dating

V SEMESTER ZOOLOGY FOSSILS AND FOSSIL DATING Fossils can include anything that gives an indication of the existence of prehistoric organisms. The Latin word Fossilium means ‘dug out’, which in earlier times meant to include any traces of body of animals and plants buried and preserved by natural causes. George Curvier (1769-1832) is considered ‘Father of palaeontology’, who studied fossils scientifically to develop phylogenies. Types of fossils Based on the mode of formation of fossils, they can be categorised in several types. Fossilisation is a rare phenomenon, which takes place under specialised conditions. The study of natural process of death, burial, decomposition, preservation and transformation into fossil is called taphonomy. Fossils are the only direct evidence of the biological events in the history of earth and hence important in the understanding and construction of the evolutionary history of different groups of animals and plants. 1. Petrifaction Petrifaction is molecule-by-molecule replacement of organic matter by inorganic compounds, viz. silica, calcium carbonate or iron pyrites. It literally means “turned into stone” and takes place in buried situations, particularly at the bottom of lakes, ponds or sea, where there are sediments rich in calcium carbonate and silica. Over millions of years, inorganic matter replaces the entire bony material, making an exact replica of the original. By this time sediments transform into sedimentary rocks, in which fossils can remain preserved for a long time. Most of the old fossils are petrified, e.g. shells of molluscs, arthropods and fish skeletons. 2. Preservation of footprints When animals walk on wet soil and sand, they leave trail of footprints or limbless animals and worms may leave tracks and trails in mud. -

Portraits from Our Past

M1634 History & Heritage 2016.indd 1 15/07/2016 10:32 Medics, Mechanics and Manchester Charting the history of the University Joseph Jordan’s Pine Street Marsden Street Manchester Mechanics’ School of Anatomy Medical School Medical School Institution (1814) (1824) (1829) (1824) Royal School of Chatham Street Owens Medicine and Surgery Medical School College (1836) (1850) (1851) Victoria University (1880) Victoria University of Manchester Technical School Manchester (1883) (1903) Manchester Municipal College of Technology (1918) Manchester College of Science and Technology (1956) University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (1966) e University of Manchester (2004) M1634 History & Heritage 2016.indd 2 15/07/2016 10:32 Contents Roots of the University 2 The University of Manchester coat of arms 8 Historic buildings of the University 10 Manchester pioneers 24 Nobel laureates 30 About University History and Heritage 34 History and heritage map 36 The city of Manchester helped shape the modern world. For over two centuries, industry, business and science have been central to its development. The University of Manchester, from its origins in workers’ education, medical schools and Owens College, has been a major part of that history. he University was the first and most Original plans for eminent of the civic universities, the Christie Library T furthering the frontiers of knowledge but included a bridge also contributing to the well-being of its region. linking it to the The many Nobel Prize winners in the sciences and John Owens Building. economics who have worked or studied here are complemented by outstanding achievements in the arts, social sciences, medicine, engineering, computing and radio astronomy. -

Catalogue of the Papers of Professor Sir William Boyd Dawkins in the John Rylands University Library of Manchester

CATALOGUE OF THE PAPERS OF PROFESSOR SIR WILLIAM BOYD DAWKINS IN THE JOHN RYLANDS UNIVERSITY LIBRARY OF MANCHESTER GEOFFREY TWEEDALE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY, UNIVERSITY OF SHEFFIELD AND TIMOTHY PROCTER HISTORY GRADUAND, CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD INTRODUCTION* According to a recent study, 'the history of the rise of geology over the past 200 years can, through British eyes at least, be seen to comprise two different but closely interconnected strands'. 1 The first relates more to Natural History and looks toward the scientific or 'pure' front. The second connects with mining and the search for raw materials and is slanted towards the industrial or 'applied' horizon. In contemplating these two strands of geological history it is interesting to note that it is the scientific branch of geology that has traditionally brought fame and fortune. In the nineteenth century it was the Victorian 'gentleman' geologist who enjoyed the greatest respect and power. Some became national figures, as their work on rock strata, geological surveys and minerals was found useful in the drive for 'imperial' expansion. These were the men who filled museums with their geological specimens, engaged in the most prominent controversies of the day, wrote books and articles and left papers - and naturally won prestige, influence and honours. 2 These protagonists of scientific geology have also been the chief interest of historians. This is despite the fact that the growth of * \\'e are grateful to Jack Morrell (Bradford University > and Hugh Torrens (Keele University) for providing references for this paper. 1 U.S. Torrens, 'Hawking history: a vital future for geology's past', Modem Geology, 13 (1988), 83-93. -

East Sussex Record Office Report of the County Archivist April 2008 to March 2009 Introduction

eastsussex.gov.uk East Sussex Record Office Report of the County Archivist April 2008 to March 2009 Introduction The year was again dominated by efforts towards achieving The Keep, the new Historical Resource Centre, but the core work of the Record Office continued more busily than ever and there was much of which to be proud. In July 2008 we took in our ten-thousandth accession, something of a milestone in the office’s own history of almost 60 years. An application to the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) for £4.9million towards the costs of The Keep was submitted by the Record Office on behalf of the capital partners, East Sussex County Council, Brighton & Hove City Council and the University of Sussex, in September. This represented around 20% of the anticipated costs of the building, since the partners remain committed to find the remainder. In December we learned our fate: that we had been unsuccessful. Feedback from the HLF indicated that ours had been an exemplary application, and one which they would have liked to have supported but, in a year when the effect of diverting HLF money to the Olympics was being felt, it was thought necessary to give precedence to some very high-profile projects. We were, of course, disappointed, but determined not to be deterred, and the partners agreed to pursue ways forward within the existing funding. Because it would further hold up the project, adding to inflation costs, but give no guarantee of success, we decided not to re-apply to the HLF, and by the end of the financial year were beginning to look at options for a less expensive building. -

Meteorite Iron in Egyptian Artefacts

SCIENTISTu u GEO VOLUME 24 NO 3 APRIL 2014 WWW.GEOLSOC.ORG.UK/GEOSCIENTIST The Fellowship Magazine of the Geological Society of London UK / Overseas where sold to individuals: £3.95 READ GEOLSOC BLOG! [geolsoc.wordpress.com] Iron from the sky Meteorite iron in Egyptian artefacts FISH MERCHANT WOMEN GEOLOGISTS BUMS ON SEATS Sir Arthur Smith Woodward, Tales of everyday sexism If universities think fieldwork king of the NHM fishes - an Online Special sells geology, they’re mistaken GEOSCIENTIST CONTENTS 06 22 10 16 FEATURES IN THIS ISSUE... 16 King of the fishes Sir Arthur Smith Woodward should be remembered for more than being caught by the Piltdown Hoax, says Mike Smith REGULARS 05 Welcome Ted Nield has a feeling that some eternal verities have become - unsellable 06 Society news What your Society is doing at home and abroad, in London and the regions 09 Soapbox Jonathan Paul says universities need to beef up their industrial links to attract students ON THE COVER: 21 Letters Geoscientist’s Editor in Chief sets the record straight 10 Iron from the sky 22 Books and arts Four new books reviewed by Catherine Meteoritics and Egyptology, two very different Kenny, Mark Griffin, John Milsom and Jason Harvey disciplines, recently collided in the laboratory, 25 People Geoscientists in the news and on the move write Diane Johnson and Joyce Tyldesley 26 Obituary Duncan George Murchison 1928-2013 27 Calendar Society activities this month ONLINE SPECIALS Tales of a woman geologist Susan Treagus recalls her experiences in the male-dominated groves of -

October 2015 PROGRAM and ABSTRACTS 171

Technical Session XI (Friday, October 16, 2015, 8:00 AM) endocasts, and more recently via digital endocasts. Although previous works provide ISOTOPIC ANALYSES OF MODERN AND FOSSIL HOMINOIDS descriptive anatomical and volume data on notoungulate endocasts that permit MACLATCHY, Laura, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States of comparative studies on relative brain size, until now such data have not been analyzed America, 48109; KINGSTON, John, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United within a phylogenetic framework, nor have anatomical differences been examined for States of America their potential phylogenetic utility. Early Miocene Ugandan fossil localities at Moroto and Napak have yielded multiple Our study combines data from previously published anatomical descriptions, natural catarrhine specimens including some of the oldest known hominoids. Isotopic analyses of endocasts, previously extracted plaster endocasts-all by other authors-and new data from the enamel of associated herbivore guilds at these sites have indicated water stressed high-resolution X-ray computed tomographic imaging to provide a broad comparative conditions consistent with broken canopy or woodland habitats. To characterize the study of notoungulate cranial endocasts and to enhance understanding of the phylogenetic dietary niches of hominoids within this paleoecological interpretation, we analyzed the interrelationships of Notoungulata. A total of 22 characters of the endocranium, 11 of isotopic signature of seven fossil catarrhine teeth, including -

The Boldest Hoax 1 Have Students Research the Time Line of Humans

Original broadcast: January 11, 2005 BEFORE WATCHING The Boldest Hoax 1 Have students research the time line of humans. Ask some students to research where Piltdown man was supposed to fit in. (Before the PROGRAM OVERVIEW hoax was revealed, Piltdown Man NOVA investigates the Piltdown hoax, the people was believed to have lived near the end of the Tertiary period during the who may have been involved, and the potential upper Pliocene epoch, more than reasons for the forgery. 1.25 million years ago.) Draw a time line on the board and have students The program: present their findings. • reviews Charles Darwin’s 1859 theory of evolution that drove the hunt 2 As students watch, have them to find the “missing link” in human development—fossil evidence for collect information for the “Great a species that would bridge the evolutionary gap between apes and Piltdown Forgery” activity on page 2. humans. • notes that while Germany, Spain, and France all had evidence of early man, Britain had none. AFTER WATCHING • relates how the skull and jawbone found at Piltdown, England, 1 Discuss the forgery with students. in 1912 were purported to belong to the earliest human ever discovered. Who in the program had the means, • states the early suspicions of some scientists who questioned the motive, and opportunity to carry out authenticity of the artifacts. the forgery? What knowledge and • reports subsequent finds that supported the legitimacy of the Piltdown techniques were necessary to pull it off? Would students consider the man: a canine tooth discovered in 1913 at the original site and a second Piltdown forgery a hoax, a crime, skull and tooth unearthed two years later just a few miles away.