1 What Animal?: Darwin's Displacement Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darwin and Religion

Darwin and religion Activity 3: Controversy Subject: RE 2 x 45 minutes Suggested preparation What do I need? Presentation: Letter 2544 Thomas Huxley to Darwin, Darwin and religion 23 November 1859 Letter 2548 Adam Sedgwick to Darwin 24 November 1859 Letter 2534 Charles Kingsley to Darwin 18 Nov 1859 Letters questions Who’s who The publication of On the Origin of Species challenged and sometimes divided Darwin’s colleagues and peers in relation to their religious belief. Letters show how reactions to Darwin’s work were divided. In this activity we explore whether or not Darwin’s work can be compatible with religious faith. 1 Darwin Correspondence Project www.darwinproject.ac.uk Cambridge University Library CC-BY-ND 2.00 What do I do? 1. Read through the letters, Who’s who? and answer the letter questions. 2. Discuss why Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection might have been controversial at the time. 3. Divide into 3 groups: Group 1: Make a case for why Darwin’s theory might not be acceptable to a religious faith (of your choosing). Group 2: Make a case for how Darwin’s theory might be accommodated by a religious faith. Group 3: Make a case for how Darwin’s theory might reject a religious perspective. 4. Present your argument to the class, using evidence from Darwin’s letters. 2 Darwin Correspondence Project www.darwinproject.ac.uk Cambridge University Library CC-BY-ND 2.00 Letter 2544 Thomas Huxley to Charles Darwin, 23 November 1859 23 Nov 1859 My dear Darwin ...Since I read Von Bär’s Essays nine years ago no work on Natural History Science I have met with has made so great an impression upon me & I do most heartily thank you for the great store of new views you have given me Nothing I think can be better than the tone of the book—it impresses those who know nothing about the subject— As for your doctrines I am prepared to go to the Stake if requisite in support of Chap. -

Natural Theology and Natural History in Darwin’S Time: Design

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ETD - Electronic Theses & Dissertations NATURAL THEOLOGY AND NATURAL HISTORY IN DARWIN’S TIME: DESIGN, DIRECTION, SUPERINTENEDENCE AND UNIFORMITY IN BRITISH THOUGHT, 1818-1876 By Boyd Barnes Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Religion May, 2008 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor James Hudnut-Beumler Professor Dale A. Johnson Professor Eugene A. TeSelle Professor Richard F. Haglund Professor James P. Byrd William Buckland “The evidences afforded by the sister sciences exhibit indeed the most admirable proofs of design originally exerted at the Creation: but many who admit these proofs still doubt the continued superintendence of that intelligence, maintaining that the system of the Universe is carried on by the force of the laws originally impressed upon matter…. Such an opinion … nowhere meets with a more direct and palpable refutation, than is afforded by the subserviency of the present structure of the earth’s surface to final causes; for that structure is evidently the result of many and violent convulsions subsequent to its original formation. When therefore we perceive that the secondary causes producing these convulsions have operated at successive epochs, not blindly and at random, but with a direction to beneficial ends, we see at once the proofs of an overruling Intelligence continuing to superintend, direct, modify, and control the operation of the agents, which he originally ordained.” – The Very Reverend William Buckland (1784-1856), DD, FRS, Reader in Geology and Canon of Christ Church at the University of Oxford, President of the Geological Society of London, President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, Dean of Westminster. -

In This Index Fellow of the Royal Society Is Abbreviated to FRS and President to PRS

Index In this index Fellow of the Royal Society is abbreviated to FRS and president to PRS. Abbott, E. C. see Gadow, Hans and E. C. Abbott automata 51, 51nn4–5 Abel, Frederick Augustus 177, 177n1, 179 Avebury, Baron see Lubbock, John Aberdeen University, Huxley as rector 35, 36, 36n1, 42–3; his inaugural address 42, 43n1 Abney, William de Wiveleslie 85, 85n2, 115, 148, 149, 187, 220 Babbage, Charles 269, 269n2 ‘The solar spectrum ...’ 143, 144n1, 145 Baer, Karl Ernst von 12 Acade´mie Royale des Sciences, Paris 145 Autobiography 12n3 Acland, Sir Henry Wentworth 240, 240n3, RS Copley Medal awarded to 12n3 241, 242 Baeyer, Johann Friedrich Wilhelm von 118, 119n4 acquired characteristics 23 [Bale], [unidentified] 31 advertising 261, 261n2 Balfour, Arthur James Macmillan’s advertisement for Huxley: Lessons Foundation of belief 307; Huxley’s reply to: in elementary physiology 136–7 ‘Mr Balfour’s attack on agnosticism’ 307n2, Airy, George Biddell 40, 40n3 308 Albert, Prince Consort 269n2 Balfour, Francis Maitland xvi, 40n4, 44, 44n1, Allchin, William Henry 48, 48n1, 61, 70, 81 52–3, 53n1, 65, 67, 231 Alter, Peter Huxley on 79, 142 The reluctant patron ... xiin5, xviin14 lectures by 68 amphioxus 55, 56, 232, 233 ‘On the development of the spinal nerves in anatomy 8, 28, 80, 81, 234 elasmobranch fishes’ 65n6, 66 animals, cruelty to 73, 73n1 death xvi, 79, 79n1; Foster’s obituary notice 88, see also vivisection 89n1 Antarctic expedition, Australian colonies proposal see also Foster, M. and Francis M. Balfour for 193, 193n1 Bancroft, Marie Effie -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook #35588: <TITLE>

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Scientific Papers by Sir George Howard Darwin, by George Darwin This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Scientific Papers by Sir George Howard Darwin Volume V. Supplementary Volume Author: George Darwin Commentator: Francis Darwin E. W. Brown Editor: F. J. M. Stratton J. Jackson Release Date: March 16, 2011 [EBook #35588] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SCIENTIFIC PAPERS *** Produced by Andrew D. Hwang, Laura Wisewell, Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (The original copy of this book was generously made available for scanning by the Department of Mathematics at the University of Glasgow.) transcriber's note The original copy of this book was generously made available for scanning by the Department of Mathematics at the University of Glasgow. Minor typographical corrections and presentational changes have been made without comment. This PDF file is optimized for screen viewing, but may easily be recompiled for printing. Please see the preamble of the LATEX source file for instructions. SCIENTIFIC PAPERS CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS C. F. CLAY, Manager Lon˘n: FETTER LANE, E.C. Edinburgh: 100 PRINCES STREET New York: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS Bom`y, Calcutta and Madras: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd. Toronto: J. M. DENT AND SONS, Ltd. Tokyo: THE MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA All rights reserved SCIENTIFIC PAPERS BY SIR GEORGE HOWARD DARWIN K.C.B., F.R.S. -

Essays on Francis Galton, George Darwin and the Normal Curve of Evolutionary Biology, Mathematical Association, 2018, 127 Pp, £9.00, ISBN 978-1-911616-03-0

This work by Dorothy Leddy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. This is the author’s original submitted version of the review. The finally accepted version of record appeared in the British Journal for the History of Mathematics, 2019, 34:3, 195-197, https://doi.org/10.1080/26375451.2019.1617585 Chris Pritchard, A Common Family Weakness for Statistics: Essays on Francis Galton, George Darwin and the Normal Curve of Evolutionary Biology, Mathematical Association, 2018, 127 pp, £9.00, ISBN 978-1-911616-03-0 George Darwin, born halfway through the nineteenth century into a family to whom the principle of evolution was key, at a time when the use of statistics to study such a concept was in its infancy, found a kindred spirit in Francis Galton, 23 years his senior, who was keen to harness statistics to aid the investigation of evolutionary matters. George Darwin was the fifth child of Charles Darwin, the first proponent of evolution. He initially trained as a barrister and was finally an astronomer, becoming Plumian Professor of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy at Cambridge University and President of the Royal Astronomical Society. In between he was a mathematician and scientist, graduating as Second Wrangler in the Mathematics Tripos in 1868 from Trinity College Cambridge. Francis Galton was George Darwin’s second cousin. He began his studies in medicine, turning after two years to mathematics at Trinity College Cambridge. -

University of Southampton Research Repository

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Alastair Paynter (2018) “The emergence of libertarian conservatism in Britain, 1867-1914”, University of Southampton, Department of History, PhD Thesis, pp. 1-187. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES History The emergence of libertarian conservatism in Britain, 1867-1914 by Alastair Matthew Paynter Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2018 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES History Doctor of Philosophy THE EMERGENCE OF LIBERTARIAN CONSERVATISM IN BRITAIN, 1867-1914 by Alastair Matthew Paynter This thesis considers conservatism’s response to Collectivism during a period of crucial political and social change in the United Kingdom and the Anglosphere. The familiar political equipoise was disturbed by the widening of the franchise and the emergence of radical new threats in the form of New Liberalism and Socialism. Some conservatives responded to these changes by emphasising the importance of individual liberty and the preservation of the existing social structure and institutions. -

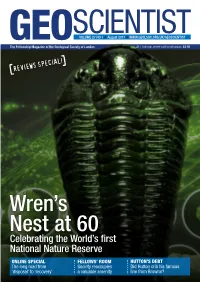

Wren's Nest at 60

SCIENTISTVOLUME 27 NO 7 ◆ August 2017 ◆ WWW.GEOLSOC.ORG.UK/GEOSCIENTIST GEOThe Fellowship Magazine of the Geological Society of London UK / Overseas where sold to individuals: £3.95 ] [REVIEWS SPECIAL! Wren’s Nest at 60 Celebrating the World’s first National Nature Reserve ONLINE SPECIAL FELLOWS’ ROOM HUTTON’S DEBT The long road from Society reoccupies Did Hutton crib his famous ‘disposal’ to ‘recovery’ a valuable amenity line from Browne? GEOSCIENTIST CONTENTS 17 24 10 25 REGULARS IN THIS ISSUE... 05 Welcome Ted Nield says true ‘scientific outreach’ is integral, not a strap-on prosthetic. 06 Society News What your Society is doing at home and abroad, in London and the regions. 09 Soapbox Mike Leeder discusses Hutton’s possible debt to Sir Thomas Browne ON THE COVER: 16 Calendar Society activities this month 10 CATCHING THE DUDLEY BUG 20 Letters New The state of Geophysics MSc courses in the Andrew Harrison looks back on the UK; The new CPD system (continued). 61st year of the World’s first NNR 22 Books and arts Thirteen new books reviewed by Dawn Brooks, Malcolm Hart, Gordon Neighbour, Calymene blumenbachii or ‘Dudley Bug’. James Montgomery, Wendy Cawthorne, Jeremy Joseph, David Nowell, Martin Brook, Alan Golding, Mark Griffin, Courtesy, Dudley Museum Services Hugh Torrens, Nina Morgan and Amy-Jo Miles 24 People Geoscientists in the news and on the move 27 Obituary Robin Temple Hazell 1927 - 2017 RECOVERY V. DISPOSAL William Braham 1957 -2016 NLINE Chris Berryman on applying new guidance 27 Obituary affecting re-use of waste soil materials. -

Mallock Social Philosophy Political Economy with a New Introduction by Modern History

Mallock Social Philosophy Political Economy With a new introduction by Modern History THE LIMITS OF PURE DEMOCRACY H. Lee Cheek, Jr. W. H. Mallock With a new introduction by H. Lee Cheek, Jr. The 1910s was a decade in which theories of socialism, pacifism, and collectivism flowered. Publicists and playwrights from Sidney Webb to George Bernard Shaw expressed not just belief in “utopianism” but a vigorous assault The Limits of on the existing political and economic order. Less well known is how a group of Tory thinkers laid the foundations of a conservative counter-attack expressed with equal literary and intellectual brilliance. Foremost among them was W. H. The Limits of Mallock. In The Limits of Pure Democracy he argued that the pseudo-populist leaders of the political party system promise everything but deliver only the end of parties as such. For Mallock, what starts with populism ends in dictatorship. The Russian Revolution was simply the historical outcome of utopian socialist visions that were more dedicated to destroying the present system of things than bringing about a revitalized future. Mallock’s book explains how the modern free market succeeds through competition in increasing output, broadening occupational opportunities, and multiplying the numbers of skilled professionals. In contrast, welfare schemes serve to deepen poverty by spreading wealth so evenly that incentives to work decline and personal savings are eliminated. These arguments have become commonplace today. But at the time they PURE DEMOCRACY served as an incendiary reminder that class warfare works in both directions. PURE Mallock was a remarkably talented writer who made the case against exaggerated expectations, a nascent welfare system, and mass political parties led by oligarchs. -

Thomas Henry Huxley

A Most Eminent Victorian: Thomas Henry Huxley journals.openedition.org/cve/526 Résumé Huxley coined the word agnostic to describe his own philosophical framework in part to distinguish himself from materialists, atheists, and positivists. In this paper I will elaborate on exactly what Huxley meant by agnosticism by discussing his views on the distinctions he drew between philosophy and science, science and theology, and between theology and religion. His claim that theology belonged to the realm of the intellect while religion belonged to the realm of feeling served as an important strategy in his defense of evolution. Approaching Darwin’s theory in the spirit of Goethe’s Thatige Skepsis or active skepticism, he showed that most of the “scientific” objections to evolution were at their root religiously based. Huxley maintained that the question of “man’s place in nature” should be approached independently of the question of origins, yet at the same time argued passionately and eloquently that even if humans shared a common a origin with the apes, this did not make humans any less special. Because evolution was so intertwined with the questions of belief, of morals and of ethics, and Huxley was the foremost defender of Darwin’s ideas in the English- speaking world, he was at the center of the discussions as Victorians struggled with trying to reconcile the growing gulf between science and faith. Haut de page Entrées d’index Mots-clés : croyance, époque victorienne, Bible, agnosticisme, Metaphysical Society, conversion, catholicisme, Dracula, Martineau (Harriet), Huxley (Thomas Henry) Keywords: belief, Victorian times, Bible, agnosticism, Metaphysical Society, conversion, Catholicism, Dracula, Martineau (Harriet), Huxley (Thomas Henry) Haut de page 1/19 Texte intégral PDF Signaler ce document The line between biology, morals, and magic is still not generally known and admitted. -

Calcul Des Probabilités

1913.] SHORTER NOTICES. 259 by series to the Legendre, Bessel, and hypergeometric equations will be useful to the student. The last of the important Zusâtze (see pages 637-663) is devoted to an exposition of the theory of systems of simul taneous differential equations of the first order. Having thus passed in quick review the contents of the book, it is now apparent that the translator has certainly accom plished his purpose of making it more useful to the student of pure mathematics. There remains the question whether there are not other additions which would have been desirable in accomplishing this purpose. There is at least one which, in the reviewer's opinion, should have been inserted. In connection with the theory of formal integration by series it would have been easy to insert a proof of the convergence in general of the series for the case of second order equations; and one can but regret that this was not done. Such a treat ment would have required only a half-dozen pages; and it would have added greatly to the value of this already valuable section. The translator's reason for omitting it is obvious; he was making no use of function-theoretic considerations, and such a proof would have required the introduction of these notions. But the great value to the student of having at hand this proof, for the relatively simple case of second order equations, seems to be more than a justification for departing in this case from the general plan of the book; it seems indeed to be a demand for it. -

Is Life Worth Living? 1

Is Life Worth Living? 1 A free download from http://manybooks.net Is Life Worth Living? Project Gutenberg's Is Life Worth Living?, by William Hurrell Mallock This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re−use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Is Life Worth Living? Author: William Hurrell Mallock Release Date: December 2, 2005 [EBook #17201] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO−8859−1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK IS LIFE WORTH LIVING? *** Produced by David Garcia, Stacy Brown Thellend and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net IS LIFE WORTH LIVING? BY WILLIAM HURRELL MALLOCK Is Life Worth Living? 2 AUTHOR OF 'THE NEW REPUBLIC' ETC. * * * * * 'Man walketh in a vain shadow, and disquieteth himself in vain.' 'How dieth the wise man? As the fool.... That which befalleth the sons of men befalleth the beasts, even one thing befalleth them; as the one dieth so dieth the other, yea they have all one breath; so that man hath no preeminence above a beast; for all is vanity.' '[Greek: talaipôros egô anthrôpos, tis me rudetai ek tou sômatos tou thanatou toutou];' * * * * * NEW YORK G.P. PUTNAM'S SONS 182 Fifth Avenue 1879 I INSCRIBE THIS BOOK TO JOHN RUSKIN _TO JOHN RUSKIN._ My dear Mr. Ruskin,−−You have given me very great pleasure by allowing me to inscribe this book to you, and for two reasons; for I have two kinds of acknowledgment that I wish to make to you−−first, that of an intellectual debtor to a public teacher; secondly, that of a private friend to the kindest of private friends. -

The Journal of William Morris Studies

The Journal of William Morris Studies volume xix number 4 summer 2012 Editorial Patrick O’Sullivan 3 Obituary: Peter Preston Peter Faulkner 4 A William Morris Letter Peter Faulkner 7 Morris and Devon Great Consols Florence S. Boos & Patrick O’Sullivan 11 Morris and Pre-Raphaelitism Peter Faulkner 40 ‘And my deeds shall be remembered, and my name that once was nought’: Regin’s Role in Sigurd the Volsung and the Fall of the Niblungs Kathleen Ullal 63 Morris’s Late Style and the Irreconcilabilities of Desire Ingrid Hanson 74 Reviews. Edited by Peter Faulkner 85 William Morris, The Wood Beyond the World, edited by Robert Boenig (Phillippa Bennett) 85 Joseph Phelan, The Music of Verse. Metrical Experiment in Nineteenth-Century Poetry (Peter Faulkner) 89 the journal of william morris studies .summer 2012 Martin Crick, The History of the William Morris Society (Martin Stott) 92 Fiona MacCarthy, The Last Pre-Raphaelite. Edward Burne-Jones and the Victo- rian Imagination (Peter Faulkner) 96 Susie Harries, Nikolaus Pevsner: The Life (John Purkis) 100 Paul Ward, Red Flag and Union Jack: Englishness, Patriotism and the British Left, 1881–1924 (Gabriel Schenk) 103 James C. Whorton, The Arsenic Century (Mike Foulkes & Patrick O’Sullivan) 105 Guidelines for Contributors 109 Notes on Contributors 111 ISSN: 1756-1353 Editor: Patrick O’Sullivan ([email protected]) Reviews Editor: Peter Faulkner ([email protected]) Designed by David Gorman ([email protected]) Printed by the Short Run Press, Exeter, UK (http://www.shortrunpress.co.uk/) All material printed (except where otherwise stated) copyright the William Mor- ris Society.