Field L/O R3 11/17/07 11:54 AM Page 131

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHECKLIST and BIOGEOGRAPHY of FISHES from GUADALUPE ISLAND, WESTERN MEXICO Héctor Reyes-Bonilla, Arturo Ayala-Bocos, Luis E

ReyeS-BONIllA eT Al: CheCklIST AND BIOgeOgRAphy Of fISheS fROm gUADAlUpe ISlAND CalCOfI Rep., Vol. 51, 2010 CHECKLIST AND BIOGEOGRAPHY OF FISHES FROM GUADALUPE ISLAND, WESTERN MEXICO Héctor REyES-BONILLA, Arturo AyALA-BOCOS, LUIS E. Calderon-AGUILERA SAúL GONzáLEz-Romero, ISRAEL SáNCHEz-ALCántara Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada AND MARIANA Walther MENDOzA Carretera Tijuana - Ensenada # 3918, zona Playitas, C.P. 22860 Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur Ensenada, B.C., México Departamento de Biología Marina Tel: +52 646 1750500, ext. 25257; Fax: +52 646 Apartado postal 19-B, CP 23080 [email protected] La Paz, B.C.S., México. Tel: (612) 123-8800, ext. 4160; Fax: (612) 123-8819 NADIA C. Olivares-BAñUELOS [email protected] Reserva de la Biosfera Isla Guadalupe Comisión Nacional de áreas Naturales Protegidas yULIANA R. BEDOLLA-GUzMáN AND Avenida del Puerto 375, local 30 Arturo RAMíREz-VALDEz Fraccionamiento Playas de Ensenada, C.P. 22880 Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Ensenada, B.C., México Facultad de Ciencias Marinas, Instituto de Investigaciones Oceanológicas Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Carr. Tijuana-Ensenada km. 107, Apartado postal 453, C.P. 22890 Ensenada, B.C., México ABSTRACT recognized the biological and ecological significance of Guadalupe Island, off Baja California, México, is Guadalupe Island, and declared it a Biosphere Reserve an important fishing area which also harbors high (SEMARNAT 2005). marine biodiversity. Based on field data, literature Guadalupe Island is isolated, far away from the main- reviews, and scientific collection records, we pres- land and has limited logistic facilities to conduct scien- ent a comprehensive checklist of the local fish fauna, tific studies. -

Forage Fish Management Plan

Oregon Forage Fish Management Plan November 19, 2016 Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Marine Resources Program 2040 SE Marine Science Drive Newport, OR 97365 (541) 867-4741 http://www.dfw.state.or.us/MRP/ Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Purpose and Need ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Federal action to protect Forage Fish (2016)............................................................................................ 7 The Oregon Marine Fisheries Management Plan Framework .................................................................. 7 Relationship to Other State Policies ......................................................................................................... 7 Public Process Developing this Plan .......................................................................................................... 8 How this Document is Organized .............................................................................................................. 8 A. Resource Analysis .................................................................................................................................... -

MERLUZA COMÚN Merluccius Gayi Gayi (Guichenot, 1848)

Ficha Pesquera Noviembre - 2008 MERLUZA COMÚN Merluccius gayi gayi (Guichenot, 1848) I. ANTECEDENTES DEL RECURSO Antecedentes biológicos Familia Merlucciidae Orden Gadiformes Clase Actinopterygii Hábitat Batidemersal Alimentación Zooplancton (eufausidos), Necton (peces juveniles), Zoobentos (crustáceos decápodos). Canibalismo Tamaño máximo (cm) 80 cm LT Talla modal 2008 (cm) 35 cm LT (industrial); 35 cm LT (espinel); 37 cm LT (enmalle) Longevidad (años) 15 años Edad de reclutamiento 2-3 años Ciclo de vida El ciclo de vida de esta especie está fuertemente asociado a la columna de agua sobre el área de la plataforma y talud continental de Chile centro-sur (zona nerítica), aunque bajo circunstancias ambientales extraordinarias es posible que ciertos procesos se verifiquen en la zona oceánica aledaña. El ciclo de vida comienza con el desove, el cual se realiza durante todo el año (desovante parcial) aunque el período de mayor intensidad se verifica en invierno-primavera, y un período de desove secundario en febrero- marzo de cada año. Las principales áreas de desove están cercanas a la costa entre Papudo (32º30’ LS) y Bahía San Pedro (40º50’ LS), los huevos desovados son fecundados en el área demersal de la zona nerítica, pasando las larvas a formar parte del necton por un periodo hasta el momento no determinado, y estando sujetas a los típicos procesos de transporte y advección que ocurren a lo largo de la zona centro sur de Chile. Después de un año a un año y medio, los juveniles de merluza común se reclutan al stock, habitando en áreas cercanas a la costa. A partir de los 3 años (34 cm LT), los ejemplares se reclutan a la pesquería y a partir de los 3,5 años (35-37 cm LT) alcanzan la edad de madurez sexual al 50%, constituyéndose en parte del stock adulto, el cual esta asociado a la contracorriente subsuperficial de Chile y Perú (Corriente de Gunther). -

HAKES of the WORLD (Family Merlucciidae)

ISSN 1020-8682 FAO Species Catalogue for Fishery Purposes No. 2 HAKES OF THE WORLD (Family Merlucciidae) AN ANNOTATED AND ILLUSTRATED CATALOGUE OF HAKE SPECIES KNOWN TO DATE FAO Species Catalogue for Fishery Purposes No. 2 FIR/Cat. 2 HAKES OF THE WORLD (Family Merlucciidae) AN ANNOTATED AND ILLUSTRATED CATALOGUE OF HAKE SPECIES KNOWN TO DATE by D. Lloris Instituto de Ciencias del Mar (CMIMA-CSIC) Barcelona, Spain J. Matallanas Facultad de Ciencias Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain and P. Oliver Instituto Español de Oceanografia Palma de Mallorca, Spain FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2005 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ISBN 92-5-104984-X All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Chief, Publishing Management Service, Information Division, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy by e-mail to [email protected] © FAO 2005 Hakes of the World iii PREPARATION OF THIS DOCUMENT his catalogue was prepared under the FAO Fisheries Department Regular Programme by the Species Identification and TData Programme in the Marine Resources Service of the Fishery Resources Division. -

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS of the 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project March 2018 DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project Citation: Aguilar, R., García, S., Perry, A.L., Alvarez, H., Blanco, J., Bitar, G. 2018. 2016 Deep-sea Lebanon Expedition: Exploring Submarine Canyons. Oceana, Madrid. 94 p. DOI: 10.31230/osf.io/34cb9 Based on an official request from Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment back in 2013, Oceana has planned and carried out an expedition to survey Lebanese deep-sea canyons and escarpments. Cover: Cerianthus membranaceus © OCEANA All photos are © OCEANA Index 06 Introduction 11 Methods 16 Results 44 Areas 12 Rov surveys 16 Habitat types 44 Tarablus/Batroun 14 Infaunal surveys 16 Coralligenous habitat 44 Jounieh 14 Oceanographic and rhodolith/maërl 45 St. George beds measurements 46 Beirut 19 Sandy bottoms 15 Data analyses 46 Sayniq 15 Collaborations 20 Sandy-muddy bottoms 20 Rocky bottoms 22 Canyon heads 22 Bathyal muds 24 Species 27 Fishes 29 Crustaceans 30 Echinoderms 31 Cnidarians 36 Sponges 38 Molluscs 40 Bryozoans 40 Brachiopods 42 Tunicates 42 Annelids 42 Foraminifera 42 Algae | Deep sea Lebanon OCEANA 47 Human 50 Discussion and 68 Annex 1 85 Annex 2 impacts conclusions 68 Table A1. List of 85 Methodology for 47 Marine litter 51 Main expedition species identified assesing relative 49 Fisheries findings 84 Table A2. List conservation interest of 49 Other observations 52 Key community of threatened types and their species identified survey areas ecological importanc 84 Figure A1. -

Updated Checklist of Marine Fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the Proposed Extension of the Portuguese Continental Shelf

European Journal of Taxonomy 73: 1-73 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2014.73 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2014 · Carneiro M. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9A5F217D-8E7B-448A-9CAB-2CCC9CC6F857 Updated checklist of marine fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf Miguel CARNEIRO1,5, Rogélia MARTINS2,6, Monica LANDI*,3,7 & Filipe O. COSTA4,8 1,2 DIV-RP (Modelling and Management Fishery Resources Division), Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, Av. Brasilia 1449-006 Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 3,4 CBMA (Centre of Molecular and Environmental Biology), Department of Biology, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] * corresponding author: [email protected] 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:90A98A50-327E-4648-9DCE-75709C7A2472 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:1EB6DE00-9E91-407C-B7C4-34F31F29FD88 7 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:6D3AC760-77F2-4CFA-B5C7-665CB07F4CEB 8 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:48E53CF3-71C8-403C-BECD-10B20B3C15B4 Abstract. The study of the Portuguese marine ichthyofauna has a long historical tradition, rooted back in the 18th Century. Here we present an annotated checklist of the marine fishes from Portuguese waters, including the area encompassed by the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf and the Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ). The list is based on historical literature records and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history collections, together with new revisions and occurrences. -

New Zealand Fishes a Field Guide to Common Species Caught by Bottom, Midwater, and Surface Fishing Cover Photos: Top – Kingfish (Seriola Lalandi), Malcolm Francis

New Zealand fishes A field guide to common species caught by bottom, midwater, and surface fishing Cover photos: Top – Kingfish (Seriola lalandi), Malcolm Francis. Top left – Snapper (Chrysophrys auratus), Malcolm Francis. Centre – Catch of hoki (Macruronus novaezelandiae), Neil Bagley (NIWA). Bottom left – Jack mackerel (Trachurus sp.), Malcolm Francis. Bottom – Orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus), NIWA. New Zealand fishes A field guide to common species caught by bottom, midwater, and surface fishing New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No: 208 Prepared for Fisheries New Zealand by P. J. McMillan M. P. Francis G. D. James L. J. Paul P. Marriott E. J. Mackay B. A. Wood D. W. Stevens L. H. Griggs S. J. Baird C. D. Roberts‡ A. L. Stewart‡ C. D. Struthers‡ J. E. Robbins NIWA, Private Bag 14901, Wellington 6241 ‡ Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, 6011Wellington ISSN 1176-9440 (print) ISSN 1179-6480 (online) ISBN 978-1-98-859425-5 (print) ISBN 978-1-98-859426-2 (online) 2019 Disclaimer While every effort was made to ensure the information in this publication is accurate, Fisheries New Zealand does not accept any responsibility or liability for error of fact, omission, interpretation or opinion that may be present, nor for the consequences of any decisions based on this information. Requests for further copies should be directed to: Publications Logistics Officer Ministry for Primary Industries PO Box 2526 WELLINGTON 6140 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0800 00 83 33 Facsimile: 04-894 0300 This publication is also available on the Ministry for Primary Industries website at http://www.mpi.govt.nz/news-and-resources/publications/ A higher resolution (larger) PDF of this guide is also available by application to: [email protected] Citation: McMillan, P.J.; Francis, M.P.; James, G.D.; Paul, L.J.; Marriott, P.; Mackay, E.; Wood, B.A.; Stevens, D.W.; Griggs, L.H.; Baird, S.J.; Roberts, C.D.; Stewart, A.L.; Struthers, C.D.; Robbins, J.E. -

Trophic Relationships of Hake (Merluccius Capensis and M

SoV 2.10 Trophic Relationships of Hake (Merluccius capensis and M. paradoxus) and Sharks (Centrophorus squamosus, Deania calcea and D. profundorum) in the Northern (Namibia) Benguela Current region Author(s): Johannes A Iitembu and Nicole B Richoux Source: African Zoology, 50(4):273-279. Published By: Zoological Society of Southern Africa URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1080/15627020.2015.1079142 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. African Zoology 2015, 50(4): 273–279 Copyright © Zoological Society Printed in South Africa — All rights reserved of Southern Africa AFRICAN ZOOLOGY This is the final version of the article that is ISSN 1562-7020 EISSN 2224-073X published ahead of the print and online issue http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15627020.2015.1079142 Trophic relationships of hake (Merluccius capensis and M. paradoxus) and sharks (Centrophorus squamosus, Deania calcea and D. -

Mid-Atlantic Forage Species ID Guide

Mid-Atlantic Forage Species Identification Guide Forage Species Identification Guide Basic Morphology Dorsal fin Lateral line Caudal fin This guide provides descriptions and These species are subject to the codes for the forage species that vessels combined 1,700-pound trip limit: Opercle and dealers are required to report under Operculum • Anchovies the Mid-Atlantic Council’s Unmanaged Forage Omnibus Amendment. Find out • Argentines/Smelt Herring more about the amendment at: • Greeneyes Pectoral fin www.mafmc.org/forage. • Halfbeaks Pelvic fin Anal fin Caudal peduncle All federally permitted vessels fishing • Lanternfishes in the Mid-Atlantic Forage Species Dorsal Right (lateral) side Management Unit and dealers are • Round Herring required to report catch and landings of • Scaled Sardine the forage species listed to the right. All species listed in this guide are subject • Atlantic Thread Herring Anterior Posterior to the 1,700-pound trip limit unless • Spanish Sardine stated otherwise. • Pearlsides/Deepsea Hatchetfish • Sand Lances Left (lateral) side Ventral • Silversides • Cusk-eels Using the Guide • Atlantic Saury • Use the images and descriptions to identify species. • Unclassified Mollusks (Unmanaged Squids, Pteropods) • Report catch and sale of these species using the VTR code (red bubble) for • Other Crustaceans/Shellfish logbooks, or the common name (dark (Copepods, Krill, Amphipods) blue bubble) for dealer reports. 2 These species are subject to the combined 1,700-pound trip limit: • Anchovies • Argentines/Smelt Herring • -

Distribution and Abundance of Fish Eggs and Larvae in the Gulf of California

DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE OF FISH EGGS AND LARVAE IN THE GULF OF CALIFORNIA H. GEOFFREY MOSER, ELBERT H. AHLSTROM, DAVID KRAMER, and ELIZABETH G. STEVENS INTRODUCTION characteristics of the Gulf of California and to give From time to time during its 24 year history the some general background information on its iohthyo- oceanographic cruises of the California Cooperative fauna. Oceanic Fisheries Investigations ( CalCOFI) have ex- This unique body of water is bounded by arid Baja tended beyond the California Current system. One California on the west and the Mexican states of example is the multivessel NORPAC Expedition Sonora and Sinaloa on the east. It extends about 1400 which encompassed much of the northeast Pacific in km between latitudes 23 and 32 north and has an 1955. Another such example is the series of seven average width of about 150 km. Wegener (1922) pro- oceanographic cruises made into the Gulf of Cali- posed that the Gulf was formed by the separation of fornia during 1956 and 1957. Baja California from the Mexican mainland, a suppo- Ships and personnel from the National Marine sition which has been strengthened by recent investi- Fisheries Service (NMFS) and Scripps Institution gations into sea floor spreading in that region (Elders of Oceanography (SIO) took part in the seven et al., 1972). The northern + of the Gulf is separated cruises, employing methods described by Kramer et al. (1972). On the first of these cruises (5602) the 115' NMFS vessel BLACK DOUGLAS occupied 93 sta- tions from the mouth of the Gulf northward as far as Tibur6n Island from February 6 to 18, 1956 (Figure 1). -

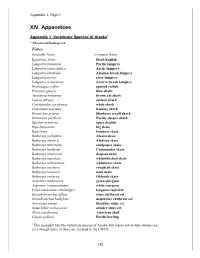

XIV. Appendices

Appendix 1, Page 1 XIV. Appendices Appendix 1. Vertebrate Species of Alaska1 * Threatened/Endangered Fishes Scientific Name Common Name Eptatretus deani black hagfish Lampetra tridentata Pacific lamprey Lampetra camtschatica Arctic lamprey Lampetra alaskense Alaskan brook lamprey Lampetra ayresii river lamprey Lampetra richardsoni western brook lamprey Hydrolagus colliei spotted ratfish Prionace glauca blue shark Apristurus brunneus brown cat shark Lamna ditropis salmon shark Carcharodon carcharias white shark Cetorhinus maximus basking shark Hexanchus griseus bluntnose sixgill shark Somniosus pacificus Pacific sleeper shark Squalus acanthias spiny dogfish Raja binoculata big skate Raja rhina longnose skate Bathyraja parmifera Alaska skate Bathyraja aleutica Aleutian skate Bathyraja interrupta sandpaper skate Bathyraja lindbergi Commander skate Bathyraja abyssicola deepsea skate Bathyraja maculata whiteblotched skate Bathyraja minispinosa whitebrow skate Bathyraja trachura roughtail skate Bathyraja taranetzi mud skate Bathyraja violacea Okhotsk skate Acipenser medirostris green sturgeon Acipenser transmontanus white sturgeon Polyacanthonotus challengeri longnose tapirfish Synaphobranchus affinis slope cutthroat eel Histiobranchus bathybius deepwater cutthroat eel Avocettina infans blackline snipe eel Nemichthys scolopaceus slender snipe eel Alosa sapidissima American shad Clupea pallasii Pacific herring 1 This appendix lists the vertebrate species of Alaska, but it does not include subspecies, even though some of those are featured in the CWCS. -

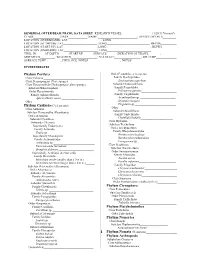

Benthic Data Sheet

DEMERSAL OTTER/BEAM TRAWL DATA SHEET RESEARCH VESSEL_____________________(1/20/13 Version*) CLASS__________________;DATE_____________;NAME:___________________________; DEVICE DETAILS_________ LOCATION (OVERBOARD): LAT_______________________; LONG______________________________ LOCATION (AT DEPTH): LAT_______________________; LONG_____________________________; DEPTH___________ LOCATION (START UP): LAT_______________________; LONG______________________________;.DEPTH__________ LOCATION (ONBOARD): LAT_______________________; LONG______________________________ TIME: IN______AT DEPTH_______START UP_______SURFACE_______.DURATION OF TRAWL________; SHIP SPEED__________; WEATHER__________________; SEA STATE__________________; AIR TEMP______________ SURFACE TEMP__________; PHYS. OCE. NOTES______________________; NOTES_______________________________ INVERTEBRATES Phylum Porifera Order Pennatulacea (sea pens) Class Calcarea __________________________________ Family Stachyptilidae Class Demospongiae (Vase sponge) _________________ Stachyptilum superbum_____________________ Class Hexactinellida (Hyalospongia- glass sponge) Suborder Subsessiliflorae Subclass Hexasterophora Family Pennatulidae Order Hexactinosida Ptilosarcus gurneyi________________________ Family Aphrocallistidae Family Virgulariidae Aphrocallistes vastus ______________________ Acanthoptilum sp. ________________________ Other__________________________________________ Stylatula elongata_________________________ Phylum Cnidaria (Coelenterata) Virgularia sp.____________________________ Other_______________________________________