Chinese Takeout Box Emoji Proposal Submitted By: Jennifer 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foodservice Disposables Guide

MANUFACTURERS REPRESENTATIVES “Connecting Partnerships” FOODSERVICE DISPOSABLES ENVIRONMENTAL MATERIALS GUIDE 5th Edition 2021 NEXUS CORPORATE HEADQUARTERS 7042 Commerce Circle Suite B, Pleasanton CA 94588 | T 800.482.6088 | F 510.567.1005 www.nexus-now.com rev. 3/21 MISSION STATEMENT OF THIS PUBLICATION “Our mission, as manufacturer’s representatives, is to strive to be good stewards to the environment in our marketplaces by educating, training and informing our customers on all of the different packaging materials and substrates that are used to make a wide array of disposable foodservice products. In this publication we also seek to advise our customers on how each packaging substrate should be used in operational applications like microwaves, freezers and ovens as well as which materials can be recycled and or composted in each respective region in the Western United States.” Chris Matson President, Nexus The information provided in this guide may vary in accuracy due to the ever changing city, state and federal rules, regulations, ordinances and laws that govern recycling, landfills and commercial compost facilities. 3 FOODSERVICE DISPOSABLES ENVIRONMENTAL MATERIALS GUIDE “Connecting Partnerships” TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 MISSION STATEMENT 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 INTRODUCTION 8 ENVIRONMENTAL WASTE 13 LANDFILLS 14 RECYCLABLES 17 INTERNATIONAL RECYCLING 18 PLASTICS 36 GOVERNMENT REGULATIONS 41 FOODSERVICE PACKAGING 43 CLEAN PACKAGING 46 BACTERIA 47 HACCP 49 FOODSERVICE GLOVES 55 MYTHS & FACTS 59 PAPER 65 GREEN 4 5 INTRODUCTION The world of foodservice packaging disposables can be very confusing in today’s ever changing marketplace. There are so many different packaging materials that are used in a variety of food applications made by hundreds of manufacturers. -

Paper Bags Can Be Customised to Your Liking and Are Produced with Quality, Competitively

PAPER PACKAGING 31 [email protected] Confectionery Kraft Bags Description: BOPP Kraft Bags 60 x 40 x 170mm Product Code: 6040170200002 Qty Per Box: 50 pcs Description: BOPP Kraft Bags 60 x 50 x 200mm Product Code: 6050200200001 Qty Per Box: 50 pcs Description: BOPP Kraft Bags 80 x 50 x 280mm Product Code: 8050280200005 Qty Per Box: 50 pcs Description: BOPP Kraft Bags 100 x 60 x 300mm Product Code: 1006030020000 Qty Per Box: 50 pcs Description: BOPP Kraft Bags 120 x 70 x 370mm Product Code: 1207037020004 Qty Per Box: 50 pcs Description: BOPP Kraft Bags 160 x 90 x 360mm Product Code: 1609036020007 Qty Per Box: 50 pcs Description: Kraft Standup Pouch 130+32x210mm Product Code: 3660538015531 Qty Per Box: 200 pcs Description: Kraft Standup Pouch 160+37x240mm Product Code: 3660538015494 Qty Per Box: 200 pcs Description: Kraft Standup Pouch 190+84x280mm Product Code: 3660538015555 Qty Per Box: 200 pcs 32 [email protected] Paper Carrier Bags* *Sizes are approx. +/- 10% Description: Paper Carrier Bag 175 x 90 x 230mm Description: Paper Carrier Bag 175 x 90 x 230mm Product Code: TR SMALL Product Code: SMALL WHITE Qty Per Box: 250 bags Qty Per Box: 250 bags Description: Paper Carrier Bag 220 x 110 x 250mm Description: Paper Carrier Bag 220 x 110 x 250mm Product Code: TR MEDIUM Product Code: MEDIUM WHITE Qty Per Box: 250 bags Qty Per Box: 250 bags Description: Paper Carrier Bag 250 x 140 x 300mm Description: Paper Carrier Bag 250 x 140 x 300mm Product Code: TR LARGE Product Code: LARGE WHITE Qty Per Box: 250 bags Qty Per Box: 250 bags Description: -

Single-Use Plastic Take-Away Food Packaging and Its Alternatives

hosted by Single-use plastic take-away food packaging and its alternatives Recommendations from Life Cycle Assessments Copyright © United Nations Environment Programme, 2020 Credit © Photos: www.shutterstock.com This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. The United Nations Environment Programme would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. Disclaimer The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Moreover, the views expressed do not necessarily represent the decision or the stated policy of the United Nations Environment Programme, nor does citing of trade names or commercial processes constitute endorsement. Suggested Citation: (UNEP 2020). United Nations Environment Programme (2020). Single-use plastic take-away food packaging and its alternatives - Recommendations from Life Cycle Assessments. Single-use plastic take-away food packaging and its alternatives -

Wordperfect Office Document

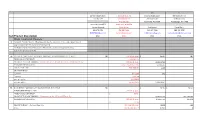

Supervisor Bosworth offered the following resolution and moved its adoption, which resolution was declared adopted after a poll of the members of the Board: RESOLUTION NO. 234 - 2014 A RESOLUTION AUTHORIZING THE AWARD OF A BID FOR JANITORIAL PRODUCTS (TNH011-2014). WHEREAS, by Resolution No. 19-2014 adopted January 7, 2014, the Commissioner of Administrative Services (the “Commissioner”) was authorized to solicit bids for the purchase of janitorial products (the “Products”); and WHEREAS, bids for the Products were received as set forth in Exhibit A attached hereto (the “Bids”); and WHEREAS, following a review of the Bids, the Commissioner has recommended an award as set forth in Exhibit B attached hereto (the “Awards”): WHEREAS, the this Board wishes to authorize the Awards as recommended by the Commissioner. NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED that the Awards as recommended by the Commissioner are hereby authorized; and be it further RESOLVED that the Supervisor be and hereby is authorized and directed to execute, on behalf of the Town, any purchase agreements and related documents, a copy of which shall be on file in the Department of Administrative Service, and to take such other related action as may be necessary to effectuate the foregoing; and be it further RESOLVED that the Office of the Town Attorney be and hereby is authorized and directed to supervise the execution of the contract documents to effectuate the Award; and be it further RESOLVED that the Comptroller be, and hereby is, authorized and directed to pay the costs thereof upon receipt of a fully executed agreement and a duly certified and executed claim therefor. -

Packaging, Labeling, and Shipping Manual January 2017

Packaging, Labeling, and Shipping Manual January 2017 1 Packaging, Shipping and Documentation Requirements . All suppliers are responsible for designing packaging that will protect the product during shipment and maintain the integrity of the product during storage. All packaging must be designed with consideration for the Environment and Recyclability. Some commodities purchased by Gentex do not fit the packaging requirements set forth in this manual. When this occurs, packaging and labeling requirements shall be documented within the PPAP and approved by Gentex. Other specific requirements may be determined based on the commodity purchased and the geographical location of the purchase. The Gentex Buyer or Material Planner will inform the supplier of these requirements. Skids . All containers must fit securely on a standard 45" x 48" (114cm x 122 cm) skid and may not over hang any side of the skid unless explicitly approved by Gentex. Total skid height (including the skid) cannot be higher than 52 inches (134 cm). Total skid load (including the skid) is not to exceed 1750 lbs (793 Kilograms) . All skids must be in good condition with no loose, damaged or missing runners or slats. All cartons shipped to Gentex on skids must be securely held to the skid using stretch wrap or banding. No mixed engineering revision levels of a Gentex part number on the same skid. International shipments must use stretch wrap to protect the shipment from salt water damage. All skids received with multiple part numbers must have labels that state “Mixed Load”. A minimum of one label on each side of the skid must be used – 4 labels per skid Shipping Cartons . -

Developing and Applying a Selection Model for Corrugated Box Precision Printing Machine Suppliers

mathematics Article Developing and Applying a Selection Model for Corrugated Box Precision Printing Machine Suppliers Chin-Tsai Lin and Cheng-Yu Chiang * Department of Business Administration, Ming Chuan University, 250 Zhong Shan N. Rd., Sec. 5, Taipei 111, Taiwan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +886-04-2206-1660-630 Abstract: Corrugated box printing machines are precision equipment produced by markedly few manufacturers. They involve high investment cost and risk. Having a corrugated box precision printing machine (CBPPM) supplier with a good reputation enables a corrugated box manufacturer to maintain its competitive advantage. Accordingly, establishing an effective CBPPM supplier selection model is crucial for corrugated box manufacturers. This study established a two-stage CBPPM supplier selection model. The first stage involved the use of a modified Delphi method to construct a supplier selection hierarchy with five criteria and 14 subcriteria. In the second stage, an analytic network process was employed to calculate the weights of criteria and subcriteria and to determine the optimal supplier. According to the results, the five criteria in the model, in descending order of importance, are quality, commitment, cost, service attitude, and reputation. This model can provide insights for corrugated box manufacturers formulating their CBPPM supplier selection strategy. Keywords: corrugated box printing machine; modified Delphi method; analytic network process (ANP); supplier 1. Introduction Citation: Lin, C.-T.; Chiang, C.-Y. The global e-commerce market is rapidly developing, with exponential growth in Developing and Applying a Selection online and TV shopping as well as demand for global shipping. Because most products Model for Corrugated Box Precision purchased online or through TV shopping channels (e-commerce) are packaged using Printing Machine Suppliers. -

Cleveland Town Topics Volume 5, December 1889

8 'Wleeltl~ 'lRc"lew of Soclet\?, 8rt anb llterature. VOL. V., No. I. CLEVELAND, 0., DECEMBER 7, 1889. PRI\E FIVE CE;\TS. A DISTINGUISHED WURKER. MISS DEBUTANTE (enthusiasticaIM: How GRAND IT JllUST DE TO BE A MAN! MR. SOFTLY, BY THE WAY, WHAT IS YOUR VOCATION? MR. SOFTLY: OH! I AM A I'ROMINE!'iT MEMBER OF A:-i INSTITUTION ON FIFTH AVENUE. MISS DEBUTANTE: INDEED, AND WHAT DO YOU DO? MR. SOFTLY: I AW-SIT IN THE CLUB WINDOW FROM TWO TO FOUR. TOWN TOPICS. Cs(ie(jUNTNEI{~ ~ONS FU S ~eat s~I\jacl\ets.wrapsaroddoaks, shoulder capes. pelerines,moffs.etc. in choice desiglls,at moderate pricej. ~b~her 181e FIFTH AVENU~ NEW YORK SECURITY AND TRUST CO" 4G 'VALL STREET. CAI>ITAIJ, $1,000,000, SUUJ)JJUS, $;;00,000. CIlA RLES S. FA I Relll LD, President. W;\1. L. STROI G, 2d Vice-President. WII. H. APPLETV ',1st Vice-President. JOII. L. L!\MSO~, Secret:lr)'. This COOlp:tny is :tuthorizcd to art as Execulor, Trlls!l'(', Adlllinistr:ttor, Guardi:ln, Agent and Receiver. Is a legal uepository for Conrt :lnd Trllst Fllnus. Takes the ('lit ire charge of real and personal estates, collecting the rents and prolits, and :lttending- lo :III such det:lils as :In individual in like capacity could do. Receives deposits s~.iect to sight drafts, allowing intl'rest on daily balances, :lnd issues certificates of deposit IJl~aring interest. --'-------------- Fine Complexion, New ParkSorRoads TIFFANY &CO., Smooth, Soft Skin. SA~LE. UNION SQUARE, NEW YORK, Mention this :lfa,:,'a::;il/I! amI semI -1 stamps FOR • for sample of P.\CKER's TAR S(lAI'. -

Guide to the Virgil Johnson Collection of Cigarette Packages

Guide to the Virgil Johnson Collection of Cigarette Packages NMAH.AC.0645 Mimi Minnick July 1998 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Cigarette Packages, circa 1890-1997....................................................... 4 Series 2: Articles and Other Publications About Tobacco and Tobacco Collecting, 1927-1994................................................................................................................. 9 Series 3: Books About Tobacco and Tobacco Collecting...................................... -

Item Product Description Block 1 Janitorial Cleaners

2 5 6/7 11 Larmel Industry Corp. I. Janvey & Sons, Inc. Imperial Bag & paper WB Mason Co. Inc. P.O. Box 334 218 Front Street 255 Route 1 & 9 90 Nicon Street P.O. Box 335 Jersey City, NJ 07306 Hauppaugge, NY 11788 Oceanside, NY 11572 Hempstead, NY 11550 Thomas Schwartz Bruce Janvey Rick Kesten Daniel Orr Jr. 516-678-2780 516-489-9300 201-437-7440 888-926-2766 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Item Product Description Price Price Price Price Block 1 Janitorial Cleaners 1} Janitorial Cleaning System, All components must be concentrated, in a tamper proof metered dispensing package with no hand mixing required. All Products by the Same Manufacturer Meant to be used as an integrated cleaning System and products to include: A} CLEANER, NON TOXIC , GENERAL PURPOSE , ENVIRONMENTALLY SAFE NB J-fill 2/2.5L to cs $ 44.99 NB GREEN SEAL CERTIFIED J-fill- $84.20 PRODUCT YOU ARE BIDDING : JOHNSON'S GP FORWARD (J-FILL AND RTD) OR EQ. RTD 2/1.5L to cs spartan 4740 PACKING INFORMATION: j-fill- 1:256, RTD- 1:256 4-2 liters/cs GALS: 2 PER CASE RTD- $69.70 1:128 DILUTION RATE : # gallons jfill- 1280 271 # gallons RTD-768 price per gallon jfill-0.0065 price per gallon rtd- $0.09075 0.166076367 B} BATHROOM CLEANER & SCALE REMOVER, NON TOXIC NB $ 78.38 $ 72.04 ENVIRONMENTALLY SAFE J-fill 2/2.5L to cs GREEN SEAL CERTIFIED $ 60.55 PRODUCT YOU ARE BIDDING : Johnson's Crew 44 (J-Fill and RTD) or EQ spartan 4716 BCC3314700 PACKING INFORMATION : RTD 2/1.5L to cs 4-2 liters /cs 2 L 4/CS $ 52.20 DILUTION RATIO : Not Less than 1:18 J-fill- 1:18, RTD-1:18 42395 1:64 # liters Jfill- 90, liter-$0.672 8 liters 8 2 5 6/7 11 Larmel Industry Corp. -

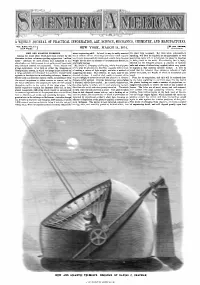

A Weekly Journal of Practical Information, Art

INFORMATION, ART, SCIENCE, MECHANICS, CHEMISTRY, AND MANUFACTURES. A WEEKLY JOURNAL OF PRACTICAL Vol. XXX.-No. 11. ] ['3 per Annum, [NEW SI!:RIES.j NEW YORK, MARCH 14, 1874. ADVANCE. NEW AND GIGANTIC TELESCOPE. nicest engineering skill. In brief, it may be safely asserted tbe exact form necessary. But little labor, comparatively Among the many ideas which have been elicited by the that a metallic mirror, of the large size above noted. suppos speaking, will here be required, as an approximateIN or very discussion in these columns regarding a gigantic or " million ing it. could be successfully constructed, would, from its great nearly true curve will, it is believed, be taken by the glass dollar " telescope, we bave recently had submitted to our weight but far more on account of its conse'luent flexure,be in fitting itself to the mold. The reflecting face is, lastly, examination one which seems to us quite novel, ingenious, practically useless. silvered by Dr. Draper's process, a solution of Rochelle and. although untried, not unpractical. It is a scheme for Mr. Daniel C. Chapman, of tl>is city, who is the originator salts and nitrate of silver being applied, which very quick a huge instrument, to be built on either the Gregorian or of the plan we are about to describe, suggests both a mod., ly dllposits a fine uniform metallic surface. It will be Cassegrainian system, in which the image is firstreceived on of making a mirror of light weight, and also a method of noted that the inventor thus obtains a reflector of light a large parabolic mirror located in a position diametrically supporting the same. -

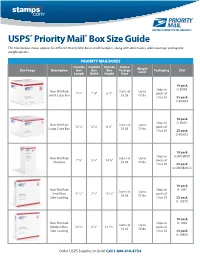

USPS Priority Mail Box Size Guide

USPS® Priority Mail® Box Size Guide The table below shows options for different Priority Mail Boxes and Envelopes, along with dimensions, online postage pricing and weight options. PRIORITY MAIL BOXES Outside Outside Outside Online Box Image Description Box Box Box Postage Weight Packaging SKU Length Width Height Price Limit 10 pack Ships in O-BOX4 Non-Flat Rate Starts at Up to 7 1/4" 7 1/4" 6 1/2" packs of Small Cube Box $5.05 70 lbs. 10 or 25 25 pack O-BOX4X 10 pack Ships in O-BOX7 Non-Flat Rate Starts at Up to 12 1/4" 12 1/4" 8 1/2" packs of Large Cube Box $5.05 70 lbs. 10 or 25 25 pack O-BOX7X 10 pack Ships in 0-SHOEBOX Non-Flat Rate Starts at Up to 7 5/8" 5 1/4" 14 5/8" packs of Shoebox $5.05 70 lbs. 10 or 25 25 pack 0-SHOEBOX-X 10 pack Non-Flat Rate Ships in O-1097 Starts at Up to Small Box, 11 5/8" 2 1/2" 13 7/16" packs of $5.05 70 lbs. Side-Loading 10 or 25 25 pack O-1097X 10 pack Non-Flat Rate Ships in O-1092 Starts at Up to Medium Box, 12 1/4" 2 7/8" 13 11/16" packs of $5.05 70 lbs. Side-Loading 10 or 25 25 pack O-1092X Order USPS Supplies in Bulk! Call 1-800-610-8734. 10 pack Non-Flat Rate Ships in O-1095X Starts at Up to Small Box, 12 7/16" 3 1/8" 15 5/8" packs of $5.05 70 lbs. -

Oyster Pub Cover For

GULF OYSTER INDUSTRY PROGRAM NATIONAL SEA GRANT COLLEGE PROGRAM ATMOS ND PH A ER IC IC N A A D E M C I O N I S L T A R N A O T I I T O A N N U . S E . C D R E E PA M RT OM MENT OF C This publication was produced by the Louisiana Sea Grant College Program for the National Sea Grant College Program, September 2003. Written by Elizabeth Coleman Design and cover photo by Robert Ray For more information about the oyster research projects sponsored through Sea Grant’s Gulf Oyster Industry Program and Oyster Disease Research Program, contact: National Sea Grant College Program NOAA, 1335 East -West Highway Silver Spring, Maryland 20910 Website: http://www.nsgo.seagrant.org/research/oysterdisease/index.html For additional copies of this publication, contact: Communications Office Louisiana Sea Grant College Program Louisiana State University Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70803 Telephone: (225) 578-6448 GS JOB 54665 AUGUST 2003 ACCT 167-13-5126-3110 MOHAWK 50-10 PLUS SOFT WHITE MATTE 80# COVER-100# TEXT MARKS Q=500 Contents 3 Foreword 4 An Industry Under Siege The traditional oyster industry in the Gulf of Mexico faces challenges that may destroy it. The Gulf Oyster Industry Program, a remarkable partnership among industry, science, and government, provides a practical and effective means for keeping the industry viable. 7 Controlling Disease The control of oyster pathogens – both those that kill oysters and those that cause human illness – is a priority. Because these pathogens occur naturally in the water, the greatest hope for success in fighting them lies in the laboratory and the hatchery, primarily through genetics research.