The Tr1nitarian Doctrine and Sources of St. Caesarius of Arles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Césaire D'arles

Textes Français/Anglais ’Association Aux Sources de la Provence poursuit la collection « Césaire d’Arles et les cinq Lcontinents ». Vous trouverez douze contributions diverses (français/anglais), telles que : ASP Césaire d’Arles « Comment j’ai fait mon édition des œuvres de Césaire » (Dom Germain Morin †), « L’émotion d’un retour à Rome » (Exposition au Vatican 2017), « Traduire Césaire à l’Université catholique d’Amérique », « Petit traité de la Grâce » (Césaire d’Arles), « Les premiers témoins du paludisme et les cinq continents en Provence » (archéologie), « Césaire d’Arles et Lérins », etc. Caesarius von Arles Nous préparons déjà le tome III Allemand (2019) sur le thème : « Hérésie et Caesario di Arles superstition chez Césaire » et le Italien tome IV (2020) sur « l’in- Cezarego z Arles uence d’Augus tin dans Polonais l’œuvre de Césaire». Cazarie de Arles Polonais Volume II Volume Tome II – Tome 神學詞語彙編 Chinois Cezarie de Arles Roumain he Association Aux Sources Cesareo de Arlés T de la Provence continues its Espagnol collection “Caesarius of Arles and the Caesarius Arelatensis Five Continents”. is volume contains Latin twelve articles (French/English), including: Цезарий Арелатский “How I published the work of Saint Caesarius of Arles” Russe (Dom Germain Morin †), “ e emotion of returning to Rome” (an exhibition at the Vatican in 2017), “Translating Caesarius at the Catholique University of America”, “A small Treatise on Grace” (Caesarius of Arles), “ e rst mention of malaria in Provence” (archaeology), “Caesarius and Lérins”, etc. Caesarius of Arles Volume III (to be published in 2019) is already in preparation on the theme of “Heresy and superstition in Caesarius”. -

Light in the Dark Places: Or, Memorial of Christian Life in the Middle Ages

Light in the Dark Places: or, Memorial of Christian Life in the Middle Ages. Author(s): Neander, Augustus (1789-1850) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: Augustus Neander began his religious studies in speculative theory, but his changing interests led him to the study of church history. In his book, Light in the Dark Places, Neander©s talent as a writer and a historian is tremendously evident; collected within this volume is an abundance of re- markable information about church history. Neander shares information about the lives of Christian individuals and com- munities during times of darkness and of triumph. Neander also reveals unknown facts about early missionaries and martyrs of the church. This historical analysis will provide today©s Christians with insight into the church©s elaborate past, so that they may learn from previous mistakes and embrace habits of righteousness. Emmalon Davis CCEL Staff Writer i Contents Title Page 1 Prefatory Material 2 Preface to the American Edition. 2 Preface. 3 Contents. 4 Part I. Operations of Christianity During and After the Confusion Produced by the 6 Irruption of the Barbarians. Introduction 7 The North African Church Under the Vandals. 8 Everinus in Germany. 19 Labours of Pious Men in France. 26 Germanus of Auxerre (Antistodorum). 27 Lupus of Troyes. 29 Cæsarius of Arles. 30 Epiphanius of Pavia. 49 Eligius, Bishop of Noyon. 50 The Abbots Euroul and Loumon. 58 Gregory the Great, Bishop of Rome. 59 Christianity in Poverty and Lowliness, and on the Sick Bed. 72 Part II. Memoirs from the History of Missions in the Middle Ages. -

Sharers in the Contemplative Virtue: Julianus Pomeriusʼs Carolingian Audience

6KDUHUVLQWKH&RQWHPSODWLYH9LUWXH-XOLDQXV3RPHULXVV &DUROLQJLDQ$XGLHQFH Josh Timmermann Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Volume 45, 2014, pp. 1-44 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\&HQWHUIRU0HGLHYDODQG5HQDLVVDQFH6WXGLHV 8&/$DOI: 10.1353/cjm.2014.0029 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/cjm/summary/v045/45.timmermann.html Access provided by Universitats-und-Stadtbibliothek Koeln (26 Aug 2014 02:59 GMT) SHARERS IN THE CONTEMPLATIVE VIRTUE: JULIANUS POMERIUS’S CAROLINGIAN AUDIENCE Josh Timmermann* Abstract: Sometime between the end of the fifth century and the early sixth, the priest, grammarian, and rhetorician Julianus Pomerius composed a hortatory guidebook for bishops entitled De vita contemplativa. In the centuries following its composition, this paranetic text became erroneously attributed to Prosper of Aquitaine, the famous defender of Augustine’s doctrine of grace in mid-fifth-century Gaul. Consequently, Pomerius’s text was lent discernible authority, both through Prosper’s well-known connection to Augus- tine as well as through the apparent Augustinianism of the text itself. The De vita contem- plativa was also often paired closely with the work of Gregory the Great, which served to further enhance the importance of the text for Carolingian bishops. As this article argues, Pomerius’s contention, that not only monks, but also worldly bishops could achieve an earthly form of perfection through a rigorous adherence to their duties as “watchmen,” proved remarkably appealing, and useful, to the Carolingian episcopate. Keywords: Julianus Pomerius; Augustine of Hippo; Prosper of Aquitaine; Gregory the Great; Carolingian bishops; Carolingian church councils; episcopal authority; Jonas of Orléans; the contemplative life; the active life. -

Industriousness

Industriousness 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Remember It is true, Idleness Laborare Carry out the All devotion Without Hell is little duty that nothing little things is est which leads full of the of each work is small are little, moment: to sloth the orare. it is in the eyes talented, but to be do what you Is false. enemy impossible of God. but heaven faithful in To work ought of and put We must to have Do all that of the little things yourself love you do is something the is into what you energetic. fun. with love. great. are doing. St. Jane de Chantal work St. Thomas Aquinas soul. St. Therese of Lisieux St. Jerome St. Josemaria St. Zita to pray. St. Benedict St. Benedict 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 When a man For work is not Let us Small is life's Obstacles? To finish only, for every We must not Sometimes they things Heroism labor; does his work man, a means of love God, be so may be present, you have to at decent livelihood, Soon comes the but at times diligently start them. work but it is the but close; insistent you just invent It seems for the sake is to means through with the Great the reward upon them out of a truism, which all those cowardice or but you so be manifold powers is,- of God, strength demanding love of comfort. often lack the found and faculties Endless repose. How cleverly it is not a simple in with which of our our rights Oft as thou bearest the devil makes decision.. -

Women's Quest for Autonomy in Monastic Life

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga UTC Scholar Student Research, Creative Works, and Honors Theses Publications 12-2019 Feminine agency and masculine authority: women's quest for autonomy in monastic life Kathryn Temple-Council University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Temple-Council, Kathryn, "Feminine agency and masculine authority: women's quest for autonomy in monastic life" (2019). Honors Theses. This Theses is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Feminine Agency and Masculine Authority: Women’s Quest for Autonomy in Monastic Life Kathryn Beth Temple-Council Departmental Honors Thesis The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga History Department Examination Date: November 12, 2019 Dr. Kira Robison Assistant Professor of History Thesis Director Michelle White UC Foundation Professor of History Department Examiner Ms. Lindsay Irvin Doyle Adjunct Instructor Department Examiner Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………....….………….1 Historical Background……………………………………...……………………….….……….6 The Sixth Century Church Women’s Monasteries and the Rule for Nuns.………………………………….……………15 The Twelfth Century Church Hildegard of Bingen: Authority Given and Taken.………………………….……………….26 The Thirteenth Century Church Clare of Assisi: A Story Re-written.……………………………………….…………………...37 The Thirteenth through Sixteenth Century Church Enclosure and Discerning Women………………………………………….……...………….49 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………...……….63 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………...…………….64 Introduction From the earliest days of Christianity, women were eager to devote themselves to religious vocation. -

Caesarius of Arles on Genesis 18

PreacJiing through Many Voices: Caesarius of Arles on Genesis 18 Hans Boersma Through Another’s Voice I would have a good sampling of different hate theology textbooks.* They theologians: Origen, the brilliant if contro- are utterly boring: typically, they versial third-eentury theologian who shaped present lifeless, meagre distilla- the Alexandrian theological traditiom St. tions of what once-upon-a-time John Chrysostom, the famous fourth- were vibrant insights conveyed century representative of the Antiochene Hans Boersma with conviction and passion, school, whose powerful preaching earned isj. / . Packer Professor of by contrast, it is nothing short of a daz- him the moniker “Golden Mouth”; and Theology at zling experience to read Augustine’s The then Caesarius, the sixth-century Western Regent College. Trinity. Likewise, following along with abbot and bishop from Arles, on the south- St. Anselm’s prayerful exploration ofwhy ern coast of France. True, my familiarity God Became Man is enough to heal even with Caesarius was limited, but compar- the most prejudiced from their instinctive ing theologians from three fairly divergent abhorrence of scholastic theology. And the traditions—Alexandrian, Antiochene, and bewitching rhetoric of Karl Barth’sChurch A gustinian— seemed a good thing to do. Dogmatics must be tempting even to ardent Or, at least, so it did at the outset. As neo-Thomists of the so-called “strict obser- I started reading Caesarius, I had an inter- vanee.” So, hoping not to turn off my esting experience. The bishop’s Sermon 83 students prematurely from their theologi- (“On the Three Men Who Appeared to cal studies, I mostly have them read the blessed Abraham”) turned out to be, well “great texts” of the history of the church— ...a meagre distillation of the vibrant using textbooks only by way of emergency, insights once conveyed with conviction when shortcuts seem unavoidable. -

Creeds the History of the Creeds

THE HISTORY OF THE- CREEDS THE HISTORY OF THE CREEDS by F. J. BADCOCK, D.D. Fellow of St Augustine's College, Canterbury Author of R.eviews and Studies, Biblical and Doctrinal The Pauline Epistles and the Epistle to the Hebrews in their Historical Setting SECOND EDITION Published far the Church Historical Society LONDON SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN CO. First Edition 1930 Second Edition, largely rewritten 1938 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN CONTENTS PART I THE APOSTLES' CREED Chap. I. INTRODUCTORY page 1 I. A Fictitious Pedigree I II. Outstanding Problems . 12 Chap. II. CREEDS AND THEIR CLASSIFICATION 14 I. Types of Creeds . 14 II. The Simple Formula 15 III. The Triple Formula 17 IV. The Rule of Faith 21 Chap. III. EARLY EASTERN CREEDS 24 I. The Epistola Apostolorum 25 II. The Old Creed of Alexandria 25 III. The Shorter Creed of the Egyptian Church Order 27 IV. The Marcosian Creed . 28 V. The Early Creed of Africa 30 VI. The Profession of the "Presbyters" at Smyrna 34 NOTES A. Texts of the Dair Balaizah Papyrus, the Marcosian Creed, the Profession of the "Presbyters" at Smyrna 35 B. The Early Creeds of Africa and of Rome 36 Chap. IV. EASTERN BAPTISMAL CREEDS OF THE FouRTH CENTURY . 38 I. Introduction 38 II. Alexandria: Arius and Euzoius, Macarius 38 III. Palestine: Eusebius of Caesarea, Cyril of Jerusalem 41 vi CONTENTS IV. Antiochene Creeds: Introduction, (a) Antioch; (b) Cappadocia; (c) Philadelphia; (d) The Creed of the Didascalia. Note; (e) Marcellus of Ancyra; (f) The Psalter of Aethelstan and the Codex Laudianus page 43 Chap. -

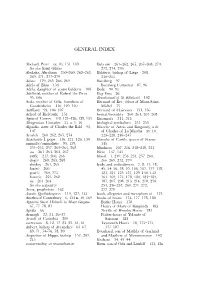

General Index

GENERAL INDEX Abelard, Peter xv, 10, 151–169 Bala{am 261–262, 265, 267–268, 270, See also Saint Gildas 272, 274, 276 Abulafi a, Abraham 250–260, 262–263, Balderic, bishop of Liège 208, 269, 271, 277–279 210–211 Adam 179, 265–266, 269 Bamberg 97 Adela of Blois 154 Bamberg Cathedral 87, 96 Adela, daughter of count Balderic 100 Bede 90–91 Adelheid, mother of Robert the Picus Beg Eriu 26 95, 106 Benedictional of St. Ethelwold 102 Aeda, mother of Oda, foundress of Bernard of Bec, abbot of Mont-Saint- Gandersheim 116, 129–130 Michel 75 Aelffl aed 93, 106–107 Bernard of Clairvaux 151, 156 Aelred of Rielvaulx 154 bestial/bestiality 260–264, 267–268 Agius of Corvey 118, 121–126, 129, 133 Biesmerée 211, 213 Albigensian Crusades 33 n. 1, 36 biological symbolism 251, 253 Alpaidis, sister of Charles the Bald 92, Blanche of Artois and Burgundy, wife 107 of Charles of La Marche xv, 10, Amalek 260–262, 265, 274 223–228, 230–247 Anastasius I, pope 116, 121, 126, 130 Blanche of Castile, queen of France animal(s)/animalistic 95, 139, 145 251–253, 257, 261–263, 268 blindness 207, 216, 218–219, 221 ass 261–263, 265, 267 Blois 137, 145 cattle 217, 260, 263 blood 1, 249, 253–254, 257–260, dog(s) 260, 263, 268 266–269, 272, 279 donkey 261, 265 body and embodiment 7, 8, 11, 18, fox(es) 260 45, 54–56, 58–59, 106, 107, 117–118, goat(s) 260, 273 121, 123, 125–127, 129–130, 132, horse(s) 225, 262 164, 169, 173, 178, 180, 183–184, ox 261–263 187, 207, 208, 213–214, 218, 250, See also serpent(s) 254, 256-257, 260, 271–272, Anna, prophetess 162 277–279 Annales Quedlinburgenses 119, 127, 133 book, allegories and metaphors of 173 Anselm of Canterbury 6, 154 n. -

Kinship, Conflict and Unity Among Roman Elites in Post-Roman Gaul

Kinship, conflict and unity among Roman elites in post-Roman Gaul: the contrasting experiences of Caesarius and Avitus Leslie Dodd The fifth century saw the end of Roman imperial power in the West. Academic debate continues about whether the empire collapsed or transformed and survived in the form of the barbarian successor states in Gaul, Italy and Spain.1 For the purposes of this chapter, the key matter is that the century began with structures of official power still apparently robust throughout the West and ended with both empire and structures seemingly supplanted by incoming barbarians.2 Yet, while the process of invasion eventually vanquished Roman political authority, Roman provincial elites survived and strove to find new ways of preserving their social, political and economic status in this new post–Roman world. As in earlier times, the fortunes of provincial elites in the later empire were intertwined with the power of the state in the form of the imperial civil service. It was through the state bureaucracy that local elites gained legal and political authority; in some instances, it was how they gained social advancement. This chapter focuses on the increasingly parochial nature of the world in which these elites found themselves. In a world where neither the church nor the new barbarian kings could provide opportunities and careers to match those of the Roman state, we will see that as competition grew for the few available posts, traditional forms of elite class consciousness came to be replaced by a strictly local form of loyalty and identity based more upon kinship than upon shared social status. -

“A Benedictine Reader Is an Exciting Volume of Sources That Includes Key Texts from the Order’S Inception in 530 Through the Sixteenth Century

“A Benedictine Reader is an exciting volume of sources that includes key texts from the Order’s inception in 530 through the sixteenth century. These ‘Benedictine Centuries’ demonstrate the rich and varied contributions that knit together the religious, political, social, and cultural fabric of European society throughout the Middle Ages and into the Early Modern period. Translated into fresh and readable English, each text contains a concise introduction that has an almost intuitive quality. This is a welcome addition to the field and is an excellent resource for both scholars and students alike.” —Alice Chapman Associate Professor of History Grand Valley State University “Perfectae Caritatis invited religious to enter into their original sources and primitive inspirations. A Benedictine Reader achieves this by creating a fascinating world of medieval monastic doctrine. This anthology opens up for any interested person ancient sources that fashioned monastic aggiornamento through the centuries. With quite remarkable scholarship, the wealth of footnotes in this volume introduces contemporary authorities promoting this renewal. Together these ancient monastics and contemporary scholars form a valuable treasure for a rebirth in monastic wisdom and insight.” —Thomas X. Davis, OCSO Abbot Emeritus, New Clairvaux Abbey “A Benedictine Reader brings together in a single volume the Venerable Bede, John of Fécamp, Abelard, Hildegard of Bingen, and other well-known figures of Western medieval monasticism. Also included are lesser known authors and works by anonymous voices. This virtual library of medieval Benedictine texts fills a gaping hole in monastic libraries and will be an excellent resource in monastic formation programs.” —Mark A. Scott, OCSO Abbot of New Melleray Peosta, Iowa 48 42 49 44 47 46 45 50 43 41 2 17 19 18 15 51 3 40 14 16 38 1 39 20 52 13 37 21 12 9 10 11 36 22 8 32 33 34 35 53 23 7 4 6 6 30 31 5 25 27 29 24 26 28 The Plan of St. -

2019 Church Fathers Resources

Are you interested in learning more about the Fathers? Below are some suggested sources to help you get started, along with a list of Church Fathers. You can also learn more by taking a course on the Fathers, which is offered regulary at the Notre Dame Graduate School of Christendom College on campus and online. Please call the office at 703 658 4304 for details. Suggested reading Altaner, Berthold. Patrology. Translated by Hilda C. Graef. Freiburg, Herder & Herder, 1958. A great single-volume overview on the writings of the Fathers. Aquilina, Mike. The Fathers of the Church: An Introduction to the First Christian Teachers. Huntington, IN: OSV. A handy popular introduction which includes a selection of short primary source texts in English translation. Benedict XVI, Pope. Church Fathers: From Clement of Rome to Augustine. General Audiences 7 March 2007-27 February 2008. San Francisco: Ignatius, 2008. ---. Church Fathers and Teachers: From Saint Leo the Great to Peter Lombard. General Audiences 5 March 2008-25 June 2008, 11 February 2009-17 June 2009, 2 September 2009-30 December 2009. San Francisco, Ignatius, 2010. These two books are the best succinct introduction to the Fathers. They are written from an informed scholarly perspective, but they make the individual authors come alive in a very readable way. Jurgens, William A. The Faith of the Early Fathers. 3 vols. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1970. This source is an English manual of brief excerpts from the Fathers arranged in historical sequence. It is a staple reference work useful for locating passages from the Fathers on particular points of doctrine. -

Preaching in Sixth-Century Arles. the Sermons of Bishop Caesarius

198 De Maeyer And Partoens Chapter 10 De Maeyer and Partoens Preaching in Sixth-Century Arles. The Sermons of Bishop Caesarius Nicolas De Maeyer and Gert Partoens 1 Introduction Preaching occupied a central place in the activities and writings of the Arlesian bishop Caesarius (470-542). This is evident from the more than 240 extant ser- mons that have been attributed to him, as well as from the repeated emphasis on the importance of preaching, found both in the bishop’s own sermons and in the Vita Caesarii that was produced shortly after his death. Although Christianity had been well established in Southern Gaul by the time Caesarius took possession of the see of Arles (502), various parts of his own and other dioceses remained poorly instructed in Christian doctrine and the Christian way of life.1 Moreover, Caesarius’ congregation was quite hetero- geneous, consisting of social groups with highly divergent levels of edu cation, literacy, and knowledge of Christian dogma. In addition, it seems that part of the population in both the city and countryside still adhered to some degree to pagan traditions and practices.2 Caesarius thus faced the task of effectively teaching Christian doctrine to a heterogeneous audience, a considerable part of which seems to have lacked even a basic knowledge of the Christian faith.3 1 For the spread of Christianity in Arles and its surroundings, see Delage in Césaire d’Arles. Sermons au peuple, Vol. 1, pp. 20-36; 118-31; Delage, “Un évêque au temps des invasions”, pp. 38- 42; Guyon, “D’Honorat à Césaire”; Klingshirn, Caesarius of Arles, pp.