Études Irlandaises, 40-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arts and Sciences By

THE IRISH UPRISING OF EASTER 1916 AND THE EMERGENCE , , OF EAMON DE VALERA AS THE LEADER OF THE IRISH REPUBLICAN MOVEMENT i\ THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE TEXAS WOMAN'S UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES BY BARBARA ANN LAMBERTH, B.S. DENTON, TEXAS AUGUST, 197 4 Texas Woman's University Denton, Texas ____J_u_n_e_26 .,_ 19 __7-1 __ _ We hereby recommend that the thesis prepared wider our supervision by Barbara Ann Lamberth "The Irish Uprising of Easter 1916 and entitled . �· � the Emergence of Eamon de Valera as the Leader of the Irish Republican Movement" be accepted as fulfilling this part of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. Committee: f\'ERSITY ,... .. ) \ ;) . TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE V CfLI\PTE R ., I. EAMON DE VALERA--THE STATESMAN . 1 II. DE VALERA--THE PRIVATE YEARS . 9 22 I I I. EASTER 1916--THE BLOOD SACRIFICE: THE PRELUDE IV. EASTER 1916--THE BLOOD SACRIFICE: MILITARY 56 ACTION . V. EASTER 1916--THE BLOOD SACRIFICE: FROM 92 DEFEAT TO VICTORY ... ........ 116 VI. DE VALERA--COMING TO LEADERSHIP .. 147 CONCLUSION APPENDIX 153 A. THE MANIFESTO OF THE IRISH VOLUNTEERS . 156 B. PROCLA MATION OF THE IRISH REPUBLIC .. • 158 c. MANIFESTO TO THE PEOPLE OF DUBLIN . 160 D. SPEECH OF DE VALERA .. , 163 E. THE MANIFESTO OF SINN FEIN F. THE TEXT OF THE SAME MANIFESTO AS PASSED BY THE DUBLIN CASTL� CENSOR • . .. � • .. 166 G. IRISH DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE . • .•169 , , 171 H. CONSTITUTION OF DAIL EIRANN • • 1 73 I. -

Cois Coiribe 2016

COIRIBE COIS Rio The Magazine for GOLD NUI Galway Galway 2020 MedTech in Galway A Changing Campus Alumni & Friends Autumn 2016 NUI Galway Affinity Card. You get, we give. You get a unique credit card and we give back to NUI Galway when you register and each year your Affinity card is active. Our introductory offer gives you a competitive rate of 2.9%¹ APR interest on balance transfers for first 12 months. bankofireland.com/alumni 1890 365 100 Lending criteria terms and conditions apply to all credit cards. Credit cards are liable to Government Stamp Duty of €30. Credit cannot be offered to anyone under 18 years of age. Bank of Ireland is regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland. ¹Available if you don’t currently hold a credit card with Bank of Ireland, whether you have an account with us or not. At the end of the introductory period the annual interest rates revert back to 2 COIS COIRIBEthe standard rate applicable to your card at that time. OMI008172 - NUIG Affinity A4_Portrait Ad_v13.indd 1 03/08/2016 12:35 NUI Galway CONTENTS 2 FOCAL ÓN UACHTARÁN NEWS Affinity Card. 4 The Year in Pictures 6 Research Round-up 10 University News You get, we give. 14 Campus News 26 Student Success FEATURES 16 A New Direction for Sport 22 1916 – Centenary Year 4 24 NASA Mission 28 A Changing Campus - Capital Development 32 Giving Stem Cells a heartbeat 34 MedTech in Galway 24 41 TG4 @ 20 42 Galway 2020 GRADUATES 36 Aoibheann McNamara 37 Paul O’Hara 38 Grads in Silicon Valley 44 Graduations GALWAY UNIVERSITY FOUNDATION 46 Empowering Excellence ALUMNI 6 18 50 Alumni Awards 38 52 Alumni Events 56 Class Notes 64 Obituaries CONTRIBUTORS Jo Lavelle, John Fallon, Ronan McGreevy, Joyce McCreevy, Joe Connolly, Dónall Ó Braonáin, Conor McNamara, Liz McConnell, Ruth Hynes, Sheila Gorham. -

Volume 1 TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999

TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999 Volume 1 TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999 Volume 1 DUBLIN PUBLISHED BY THE STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased through any bookseller, or directly from the GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS SALE OFFICE, SUN ALLIANCE HOUSE, MOLESWORTH STREET, DUBLIN 2 £12.00 €15.24 © Copyright Government of Ireland 2000 ISBN 0-7076-6434-9 P. 33331/E Gr. 30-01 7/00 3,000 Brunswick Press Ltd. ii CLÁR CONTENTS Page Foreword........................................................................................................................................................................ v Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... vii LOCAL AUTHORITIES County Councils Carlow...................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Cavan....................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Clare ........................................................................................................................................................................ 12 Cork (Northern Division) .......................................................................................................................................... 19 Cork (Southern Division)......................................................................................................................................... -

番号 曲名 Name インデックス 作曲者 Composer 編曲者 Arranger作詞

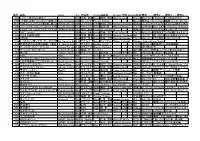

番号 曲名 Name インデックス作曲者 Composer編曲者 Arranger作詞 Words出版社 備考 備考2 備考3 備考4 595 1 2 3 ~恋がはじまる~ 123Koigahajimaru水野 良樹 Yoshiki鄕間 幹男 Mizuno Mikio Gouma ウィンズスコアWSJ-13-020「カルピスウォーター」CMソングいきものがかり 1030 17世紀の古いハンガリー舞曲(クラリネット4重奏)Early Hungarian 17thDances フェレンク・ファルカシュcentury from EarlytheFerenc 17th Hungarian century Farkas Dances from the Musica 取次店:HalBudapest/ミュージカ・ブダペスト Leonard/ハル・レナード編成:E♭Cl./B♭Cl.×2/B.Cl HL50510565 1181 24のプレリュードより第4番、第17番24Preludes Op.28-4,1724Preludesフレデリック・フランソワ・ショパン Op.28-4,17Frédéric福田 洋介 François YousukeChopin Fukuda 音楽之友社バンドジャーナル2019年2月スコアは4番と17番分けてあります 840 スリー・ラテン・ダンス(サックス4重奏)3 Latin Dances 3 Latinパトリック・ヒケティック Dances Patric 尾形Hiketick 誠 Makoto Ogata ブレーンECW-0010Sax SATB1.Charanga di Xiomara Reyes 2.Merengue Sempre di Aychem sunal 3.Dansa Lationo di Maria del Real 997 3☆3ダンス ソロトライアングルと吹奏楽のための 3☆3Dance福島 弘和 Hirokazu Fukushima 音楽之友社バンドジャーナル2017年6月号サンサンダンス(日本語) スリースリーダンス(英語) トレトレダンス(イタリア語) トゥワトゥワダンス(フランス語) 973 360°(miwa) 360domiwa、NAOKI-Tmiwa、NAOKI-T西條 太貴 Taiki Saijyo ウィンズスコアWSJ-15-012劇場版アニメ「映画ドラえもん のび太の宇宙英雄記(スペースヒーローズ)」主題歌 856 365日の紙飛行機 365NichinoKamihikouki角野 寿和 / 青葉 紘季Toshikazu本澤なおゆき Kadono / HirokiNaoyuki Honzawa Aoba M8 QH1557 歌:AKB48 NHK連続テレビ小説『あさが来た』主題歌 685 3月9日 3Gatu9ka藤巻 亮太 Ryouta原田 大雪 Fujimaki Hiroyuki Harada ウィンズスコアWSL-07-0052005年秋に放送されたフジテレビ系ドラマ「1リットルの涙」の挿入歌レミオロメン歌 1164 6つのカノン風ソナタ オーボエ2重奏Six Canonic Sonatas6 Canonicゲオルク・フィリップ・テレマン SonatasGeorg ウィリアム・シュミットPhilipp TELEMANNWilliam Schmidt Western International Music 470 吹奏楽のための第2組曲 1楽章 行進曲Ⅰ.March from Ⅰ.March2nd Suiteグスタフ・ホルスト infrom F for 2ndGustav Military Suite Holst -

57 Seanad E´ Ireann 893

57 SEANAD E´ IREANN 893 De´ Ce´adaoin, 12 Deireadh Fo´mhair, 2005 Wednesday, 12th October, 2005 10.30 a.m. RIAR NA hOIBRE Order Paper GNO´ POIBLI´ Public Business 1. Ra´itis maidir le Fore´igean Baile. Statements on Domestic Violence. 2. Ra´itis maidir leis an Aontas Eorpach. Statements on the European Union. 3. Bille na dTeangacha Oifigiu´ la (Leasu´ ) 2005 — An Dara Ce´im. Official Languages (Amendment) Bill 2005 — Second Stage. —Senators Joe O’Toole, Paul Coghlan, David Norris. Tı´olactha: Presented: 4. Bille na bPrı´osu´ n 2005 — Ordu´ don Dara Ce´im. Prisons Bill 2005 — Order for Second Stage. Bille da´ ngairtear Acht da´ chumasu´ don Bill entitled an Act to enable the Minister Aire Dlı´ agus Cirt, Comhionannais for Justice, Equality and Law Reform to agus Athcho´ irithe Dlı´ do dhe´anamh enter into agreements for the provision of comhaontuithe d’fhonn daoine is pa´irtithe certain services relating to the custody of sna comhaontuithe sin do shola´thar prisoners by persons who are parties to such seirbhı´sı´ a´irithe a bhaineann le coimea´d agreements; to provide for the certification prı´osu´ nach; do dhe´anamh socru´ maidir le of persons who will perform functions deimhniu´ cha´n a dhe´anamh ar dhaoine a under this Act pursuant to such agreements; chomhlı´onfaidh feidhmeanna faoin Acht to provide for the giving of evidence by seo de bhun na gcomhaontuithe sin; do prisoners in certain types of proceedings dhe´anamh socru´ maidir le prı´osu´ naigh do before the courts by live television link; to thabhairt fianaise i gcinea´lacha a´irithe amend the Prisons Act 1933; and to provide imeachtaı´ os comhair na gcu´ irteanna trı´ for matters connected therewith. -

Cross-Language Applicability of Linguistic Features Associated with Veracity and Deception

Cross-Language Applicability of Linguistic Features Associated with Veracity and Deception David Matsumoto, Hyisung C. Hwang & Vincent A. Sandoval Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology The Official Journal of the Society for Police and Criminal Psychology ISSN 0882-0783 Volume 30 Number 4 J Police Crim Psych (2015) 30:229-241 DOI 10.1007/s11896-014-9155-0 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Society for Police and criminal Psychology. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy J Police Crim Psych (2015) 30:229–241 DOI 10.1007/s11896-014-9155-0 Cross-Language Applicability of Linguistic Features Associated with Veracity and Deception David Matsumoto & Hyisung C. Hwang & Vincent A. Sandoval Published online: 28 August 2014 # Society for Police and criminal Psychology 2014 Abstract One technique for examining written statements or structures associated with word usage, commonly referred interview transcripts for verbal cues of veracity and lying to as Statement Analysis (SA). -

8 Su 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 0 1 2 3 4 5 6

1 SUN. to 7 SAT. 8 SUN. to 14 SAT. 15 SUN. to 21 SAT. 1 SUN. 2 MON. 3 TUE. 4 WED. 8 SUN. 9 MON. 10 TUE. 11 WED. 15 SUN. 16 MON. 17 TUE. 18 WED. PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA 3:25 Noka no Yome 00 Liga Espanola 2:00 Gone Girl*1 00 1984 Fukyu no 00 Liga Espanola 3:00 We're the Millers 3:00 La ultima muerte 20 Liga Espanola 15 Lost Time*1 1:00 MOZU Season1 00 back number 3:00 The Hungover...*1 3:00 Gekijoban 00 Liga Espanola 3:30 Night Train to 45 Macross Zero*4 00 Liga Espanola 2:45 Miss Change*1 3:00 Steel Cold 20 Liga Espanola 3:00 De Marathon*1 1:00 Yume o Ataeru 2:30 UVERworld...*3 2:45 A Muse*1 3:00 Trugschluss*1 00 Women's Golf 25 Bean*1 2:00 Ironclad...*1 23:00 Women's Tennis 20 Frankie & Alice 3:00 Kiss of the 3:45 The Matrix 3:30 Los inocentes*1 3:00 Neighbors*1 00 International 00 Frank*1 Anata ni Aitakute*1 15-16 Season*2 SF Shosetsu*5 15-16 Season*2 *1 *1 15-16 Season*2 *4 Live*3 Macross F Itsuwari 15-16 Season*2 Lisbon*1 15-16 Season*2 Winter*1 15-16 Season*2 *4 LPGA Tour 2015 Fed Cup...*2 *1 Damned*1 Revolutions*1 Premier Tennis 30 Piege*1 4 30 Jackass Presents: no Utahime*1 30 The Secret Life of 4 30 BoA Live*3 45 Yogaku BREAK*3 30 A Love Song for 4 45 A Fantastic Fear Bad Grandpa*1 Lorena Ochoa League Philippines 00 Kiru*1 00 CAMERON 00 Steamboy*1 00 Grey's Anatomy 15 The Desert Fox 10 Gekijoban Walter Mitty*1 00 The Mule*1 00 Therese 00 Muppets -

Exploring Trauma Through Fantasy

IN-BETWEEN WORLDS: EXPLORING TRAUMA THROUGH FANTASY Amber Leigh Francine Shields A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2018 Full metadata for this thesis is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this thesis: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/16004 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4 Abstract While fantasy as a genre is often dismissed as frivolous and inappropriate, it is highly relevant in representing and working through trauma. The fantasy genre presents spectators with images of the unsettled and unresolved, taking them on a journey through a world in which the familiar is rendered unfamiliar. It positions itself as an in-between, while the consequential disturbance of recognized world orders lends this genre to relating stories of trauma themselves characterized by hauntings, disputed memories, and irresolution. Through an examination of films from around the world and their depictions of individual and collective traumas through the fantastic, this thesis outlines how fantasy succeeds in representing and challenging histories of violence, silence, and irresolution. Further, it also examines how the genre itself is transformed in relating stories that are not yet resolved. While analysing the modes in which the fantasy genre mediates and intercedes trauma narratives, this research contributes to a wider recognition of an understudied and underestimated genre, as well as to discourses on how trauma is narrated and negotiated. -

The Government's Executions Policy During the Irish Civil

THE GOVERNMENT’S EXECUTIONS POLICY DURING THE IRISH CIVIL WAR 1922 – 1923 by Breen Timothy Murphy, B.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: Professor Marian Lyons Supervisor of Research: Dr. Ian Speller October 2010 i DEDICATION To my Grandparents, John and Teresa Blake. ii CONTENTS Page No. Title page i Dedication ii Contents iii Acknowledgements iv List of Abbreviations vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The ‗greatest calamity that could befall a country‘ 23 Chapter 2: Emergency Powers: The 1922 Public Safety Resolution 62 Chapter 3: A ‗Damned Englishman‘: The execution of Erskine Childers 95 Chapter 4: ‗Terror Meets Terror‘: Assassination and Executions 126 Chapter 5: ‗executions in every County‘: The decentralisation of public safety 163 Chapter 6: ‗The serious situation which the Executions have created‘ 202 Chapter 7: ‗Extraordinary Graveyard Scenes‘: The 1924 reinterments 244 Conclusion 278 Appendices 299 Bibliography 323 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to extend my most sincere thanks to many people who provided much needed encouragement during the writing of this thesis, and to those who helped me in my research and in the preparation of this study. In particular, I am indebted to my supervisor Dr. Ian Speller who guided me and made many welcome suggestions which led to a better presentation and a more disciplined approach. I would also like to offer my appreciation to Professor R. V. Comerford, former Head of the History Department at NUI Maynooth, for providing essential advice and direction. Furthermore, I would like to thank Professor Colm Lennon, Professor Jacqueline Hill and Professor Marian Lyons, Head of the History Department at NUI Maynooth, for offering their time and help. -

Fonsie Mealy Auctioneers Rare Books & Collectors' Sale December 9Th & 10Th, 2020

Rare Books & Collectors’ Sale Wednesday & Thursday, December 9th & 10th, 2020 RARE BOOKS & COLLECTORS’ SALE Wednesday & Thursday December 9th & 10th, 2020 Day 1: Lots 1 – 660 Day 2: Lots 661 - 1321 At Chatsworth Auction Rooms, Chatsworth Street, Castlecomer, Co. Kilkenny Commencing at 10.30am sharp Approx. 1300 Lots Collections from: The Library of Professor David Berman, Fellow Emeritus, T.C.D.; The Library of Bernard Nevill, Fonthill; & Select Items from other Collections to include Literature, Manuscripts, Signed Limited Editions, Ephemera, Maps, Folio Society Publications, & Sporting Memorabilia Lot 385 Front Cover Illustration: Lot 1298 Viewing by appointment only: Inside Front Cover Illustration: Lot 785 Friday Dec. 4th 10.00 – 5.00pm Inside Back Cover Illustration: Lot 337 Back Cover Illustration: Lot 763 Sunday Dec. 6th: 1.00 – 5.00 pm Monday Dec. 7th: 10.00 – 5.00 pm Online bidding available: Tuesday Dec. 8th: 10.00 – 5.00 pm via the-saleroom.com (surcharge applies) Bidding & Viewing Appointments: Via easyliveauction.com (surcharge applies) +353 56 4441229 / 353 56 4441413 [email protected] Eircode: R95 XV05 Follow us on Twitter Follow us on Instagram Admittance strictly by catalogue €20 (admits 2) @FonsieMealy @fonsiemealyauctioneers Sale Reference: 0322 PLEASE NOTE: (We request that children do not attend viewing or auction.) Fonsie Mealy Auctioneers are fully Covid compliant. Chatsworth Auction Rooms, Chatsworth St., Castlecomer, Co. Kilkenny, Ireland fm Tel: +353 56 4441229 | Email: [email protected] | Website: www.fonsiemealy.ie PSRA Registration No: 001687 Design & Print: Lion Print, Cashel. 062-61258 fm Fine Art & R are Books PSRA Registration No: 001687 Mr Fonsie Mealy F.R.I.C.S. -

Race 1 1 1 2 2 3 2 4 3 5 3 6 4 7 4 8

TOKYO SUNDAY,MAY 27TH Post Time 10:05 1 ! Race Dirt 1300m THREE−YEAR−OLDS Course Record:8Oct.05 1:16.4 MIX DES,WEIGHT FOR AGE,MAIDEN Value of race: 9,550,000 Yen 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th Added Money(Yen) 5,000,000 2,000,000 1,300,000 750,000 500,000 Stakes Money(Yen) 0 0 0 Ow. Kazuyoshi Takimoto 0 S 00000 Life00000M 00000 1 56.0 Issei Murata(4.7%,10−5−11−189,48th) Turf00000 I 00000 1 K T Dream(JPN) Dirt00000L 00000 -Fantastic Light(0.37) -Tel Quel C3,d.b. Tsuyoshi Tanaka(6.5%,6−5−3−78,100th) Course00000E 00000 Wht. .Katsura Fabulous .Sakura Fabulous 19Apr.09 Heihata Bokujo Wet 00000 Ow. S.Ogihara 0 S 00000 Life30003M 30003 1 53.0 Kazuma Harada(1.6%,1−3−1−57,109th) Turf00000 I 00000 2 Tsukuba Raijin O(JPN) Dirt30003L 00000 -Gold Allure(0.99) -Housebuster C3,ch. Yoshiyasu Takahashi(4.3%,4−1−7−81,146th) Course10001E 00000 Wht. .Wedding Rose .Gana 2Apr.09 Shoji Ogihara Wet 10001 29Apr.12 TOKYO MDN D1400St 2 2 1:28.0 10th/16 Yuta Nakatani 56.0 466, Apollo Palace 1:25.4 <1 1/4> Sound Racer <5> Succinite 8Apr.12 NAKAYAMA MDN D1800St 3347 2:00.013th/16YutaNakatani 56.0 468, Red Jackson 1:55.1 <NS> Gangan Yukoze <4> Sakura Teio 10Mar.12 NAKAYAMA NWC D1800Sl 6666 2:00.315th/16YutaNakatani 56.0 468( Grand Rafale 1:57.3 <NK> Sargon <1/2> Viganella Ow. K.Asakawa 0 S 10001 Life10001M 00000 2 B 56.0 Yuji Tannai(2.5%,6−16−13−201,61st) Turf00000 I 00000 3 Squash Again(JPN) Dirt10001L 00000 -Fasliyev(0.64) -Commander in Chief C3,b. -

Bibliography on Racism

BIBLIOGRAPHY ON RACISM Teun A. van Dijk Version 1.0, May 31, 2007 Aarim-Heriot, N. (2003). Chinese immigrants, African Americans, and racial anxiety in the United States, 1848-82. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. AARP (Organization) , Leadership Conference on Civil Rights., & Library of Congress. (2004). Voices of civil rights. Ordinary people, extraordinary stories.. Washington, D.C.: AARP. Abad Márquez, L. V., Cucó, A., & Izquierdo Escribano, A. (1993). Inmigración, pluralismo y tolerancia. Madrid: Popular. Abanes, R. (1996). American militias. Rebellion, racism & religion. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press. Abanime, E. P. (1986). Ideologies of Race and Sex in Literature: Racism and Antiracism in the African Francophone Novel. College Language Association Journal, 30(2), 125-143. Abbattista, G., & Imbruglia, G. (1992). Il razzismo e le sue storie. Napoli: Edizioni scientifiche italiane. Abbattista, G., Imbruglia, G., Associazione Sigismondo Malatesta., & Convegni malatestiani sul razzismo e le sue storie (1992). Il razzismo e le sue storie. Napoli: Edizioni scientifiche italiane. Abbott, S. (1971). The prevention of racial discrimination in Britain. London New York: published for the United Nations Institute for Training and the Institute of Race Relations by Oxford U.P. Abd Allah, G. (2000). Waqa i al-yawm al-dirasi al-khass bi-al-manahij al-tarbawiyah al-ta limiyah al-Filastiniyah wa-al-Isra iliyah. al-Quds: Markaz al-Dirasat wa-al-Tatbiqat al- Tarbawiyah. Abdel-Shehid, G. (2005). Who da man? Black masculinities and sporting cultures. Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press. Abdelaziz, T. (1987). Je, femme d'immigré. Paris: Editions du Cerf. Abdelkhalek, O. (1993). Maghrebins victimes du racisme en France, 1980-1989.