Croft, Charlie ORCID

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read an Extract

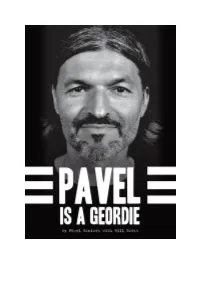

PAVEL IS A GEORDIE Pavel Srnicek Will Scott Contents 1 Pavel’s return 2 Kenny Conflict 3 Budgie crap, crap salad and crap in the bath 4 Dodgy keeper and Kevin who? 5 Got the t-shirt 6 Hooper challenge 7 Cole’s goals gone 8 Second best 9 From Tyne to Wear? 10 Pavel is a bairn 11 Stop or I’ll shoot! 12 Magpie to Owl 13 Italian job 14 Pompey, Portugal and blowing bubbles 15 Country calls 16 Testimonial 17 Slippery slope 18 Best Newcastle team 19 Best international team 20 The Naked Chef 21 Epilogue FOREWORD Spending the first ten years of my football career away from St James’ Park didn’t mean I wasn’t aware of what was going on at my home town club. As a Geordie and a Newcastle United supporter, I always kept a keen interest on what was happening on Tyneside in the early stages of my career at Southampton and Blackburn. Although it was common for clubs to sign foreign players in the early 1990s, the market wasn’t saturated the way it is now, but it was certainly unusual for teams to invest in foreign goalkeepers. And Pavel’s arrival on Tyneside certainly caused a stir. He turned up on the club’s doorstep when it was struggling at the wrong end of the old Second Division. It must have been a baptism of fire for the young Czech goalkeeper. Not only did he have to adapt to a new style of football he had to settle in to a new town and culture. -

Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale

Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale - Day 2 Wednesday 05 December 2012 10:30 Mullock's Specialist Auctioneers The Clive Pavilion Ludlow Racecourse Ludlow SY8 2BT Mullock's Specialist Auctioneers (Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale - Day 2) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1001 Rugby League tickets, postcards and handbooks Rugby 1922 S C R L Rugby League Medal C Grade Premiers awarded League Challenge Cup Final tickets 6th May 1950 and 28th to L McAuley of Berry FC. April 1956 (2 tickets), 3 postcards – WS Thornton (Hunslet), Estimate: £50.00 - £65.00 Hector Crowther and Frank Dawson and Hunslet RLFC, Hunslet Schools’ Rugby League Handbook 1963-64, Hunslet Schools’ Rugby Union 1938-39 and Leicester City v Sheffield United (FA Cup semi-final) at Elland Road 18th March 1961 (9) Lot: 1002 Estimate: £20.00 - £30.00 Keighley v Widnes Rugby League Challenge Cup Final programme 1937 played at Wembley on 8th May. Widnes won 18-5. Folded, creased and marked, staple rusted therefore centre pages loose. Lot: 1009 Estimate: £100.00 - £150.00 A collection of Rugby League programmes 1947-1973 Great Britain v New Zealand 20th December 1947, Great Britain v Australia 21st November 1959, Great Britain v Australia 8th October 1960 (World Cup Series), Hull v St Helens 15th April Lot: 1003 1961 (Challenge Cup semi-final), Huddersfield v Wakefield Rugby League Championship Final programmes 1959-1988 Trinity 19th May 1962 (Championship final), Bradford Northern including 1959, 1960, 1968, 1969, 1973, 1975, 1978 and -

'Black and Whiters': the Relative Powerlessness of 'Active' Supporter

‘Black and whiters’: The relative powerlessness of ‘active’ supporter organization mobility at English Premier League football clubs This article examines the reaction by Newcastle United supporters to the resignation of Kevin Keegan as Newcastle United manager in September 2008. Unhappy at the ownership and management structure of the club following Keegan’s departure, a series of supporter-led meetings took place that led to the creation of Newcastle United Supporters’ Club and Newcastle United Supporters’ Trust. This article draws on a non-participant observation of these meetings and argues that although there are an increasing number of ‘active’ supporters throughout English football, ultimately it is the significant number of ‘passive’ supporters who hamper the inclusion of supporters’ organizations at higher-level clubs. The article concludes by suggesting that clubs, irrespective of wealth and success, need to recognize the long-term value of supporters. Failure to do so can result in fan alienation and ultimately decline (as seen with the recent cases of Coventry City and Portsmouth). Keywords: fans; Premier League; supporter clubs; inclusion; mobilization Introduction Over the last twenty years there have been many changes to English football. In this post- Hillsborough era, the most significant change has been the introduction of a Premier League in 1992 and its growing relationship with satellite television (most notably BSkyB). This global exposure has helped increase the number of sponsors and overseas investors and has -

Welsh Guards Magazine 2011

WREGEIMLENSTAHL MGAGUAZAINRE 2D01S 1 WELSH GUARDS REGIMENTAL MAGAZINE 2011 COLONEL-IN-CHIEF Her Majesty The Queen COLONEL OF THE REGIMENT His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales KG KT GCB OM AK QSO PC ADC REGIMENTAL LIEUTENANT COLONEL Brigadier R H Talbot Rice REGIMENTAL ADJUTANT Colonel (Retd) T C S Bonas BA ASSISTANT REGIMENTAL ADJUTANT Major (Retd) K F Oultram * REGIMENTAL HEADQUARTERS Wellington Barracks, Birdcage Walk, London, SW1E 6HQ Contact Regimental Headquarters by Email: [email protected] View the Regimental Website at www.army.mod.uk/welshguards * AFFILIATIONS 5th/7th Battalion The Royal Australian Regiment HMS Campbeltown 1 WELSH GUARDS REGIMENTAL MAGAZINE CONTENTS FOREWORD WELSH GUARDS AFGHANISTAN APPEAL ADVERTISEMENTS ................................................ 95 Regimental Lieutenant Colonel ......................... 3 The Welsh Guards Afghanistan Appeal By The Commanding Officer WELSH GUARDS COLLECTION ................ 100 by Col Bonas ................................................................ 53 1st Bn Welsh Guards ................................................. 4 Charity Golf Day ......................................................... 57 WELSH GUARDS ASSOCIATION 1ST BATTALION WELSH GUARDS Ride of Respect ........................................................... 60 ASSOCIATION BRANCH REPORTS The Prince of Wales’s Company ........................ 5 Cardiff Branch .......................................................... 102 Number Two Company ........................................... 8 BATTLEFIELD -

P13 2 Layout 1

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2017 SPORTS Fleetwood to miss British Ex-Newcastle chairman Las Palmas coach Masters for child’s birth Shepherd dies aged 76 Marquez quits NEWCASTLE: Race to Dubai leader Tommy Fleetwood will miss this week’s LONDON: Former Newcastle chairman Freddy Shepherd, a pivotal BARCELONA: Las Palmas coach Manolo Marquez has become the third British Masters in Newcastle for the possible birth of his child, while figure in the club’s 1990s success, has died aged 76, his family La Liga manager to leave his job this season, calling a surprise news con- Andrew Johnston pulled out injured yesterday. Fleetwood, 26, has elected announced yesterday. Shepherd was Newcastle chairman for 10 years ference yesterday to announce his resignation after losing four of the to stay with his partner and manager Clare, who is soon to give birth to the from 1997 and eventually sold his share of the club to current owner first six games of the campaign. Las Palmas are 15th in the standings couple’s child. “I wanted to give myself every chance of play- Mike Ashley. “Freddy Shepherd sadly passed away peacefully at his with six points and Marquez’s last game in charge was a 2-0 ing this week, but being there at the birth of your child is a home last night,” his family said in a statement. “At this difficult time home defeat by Leganes on Sunday. Marquez had never special moment in anyone’s life and I would not want to the family have asked that their privacy be respected.” Tyneside-born coached a top-flight side before landing the job in July miss it,” said Fleetwood. -

The Genealogy of the Worthington Family

929.2 W8996W 1264819 ^ OENEALOGY COLLECTION ^ ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY 3 1833 00855 6349 THE GENEALOGY THE WORTHINGTON FflMILY, COMPILED KV GEORGE WORTHIXGTOX 1894. All the Worthingtoiis in America are believed to have descended from Nicholas, who came to New England in 1649, and from Capt. lohn, who is first known of in Maryland in 1675, and who died April 9, 1701, leaving several sons. Both, pi-obabh', descended from the Worthingtons of Lancashire, and such is the tradition of both families. In this genealogy will be found only those who are descended from Nicholas, and, as it is most probable that he belonged to the Shevington branch of the family of Worthington, of Worthing- " ton. County Lancashire, England, I have given the Herald's Visitations" of that branch down to 1650, at which time Nicholas was in New England. The origin of our name as given in the " Heraldic Journal, 1868," is Wearth-in-ton, from three Saxon words, meaning Farm-in-town. The old Hall at Worthington, where the family resided for seven hundred years, was recently pulled down. The Coat of Arms here given are those of the Worthingtons of Lancashire and Cheshire. While I have been exceedingly anxioiis to secure accuracy and completeness, many errors and omissions must necessarily occtir in a work of this kind. If all corrections and omissions, together with any additional records which may be in the possession of some hitherto uninterested member, or one who may not have received my "Genealogical Inquirj'," will be forwarded to the compiler, addressed to 775 Case avenue, Cleveland, Ohio, within the vear, it will be printed as an addition to the present records. -

Football Talking About Cricket! It’S Never Keep the Ashes

Section:GDN PS PaGe:1 Edition Date:050912 Edition:01 Zone: Sent at 11/9/2005 19:09 cYanmaGentaYellowblack Owen’s crash course Raikkonen rallies Chunder wonder Newcastle striker Spa success keeps Martin Kelner on a faces ugly truth McLaren man in hunt technicolour trend Kevin McCarra, page 10 ≥ Alan Henry, page 13 ≥ Screen Break, page 20 ≥ | 12.09.05 | guardian.co.uk Matthew Hoggard is mobbed after dismissing Adam Gilchrist to start a burst of four for four in 19 balls as England take control at The Oval Tom Shaw/Getty Images England’s day of destiny dawns tumultuous of all series began, was the open-top bus can be dusted down for its tion carved out for Australia by the cen- when the situation demanded and found 23,000 cheer as bad light unthinkable. Helped yesterday by a duvet ride through the city. Bad light prevented turies of Justin Langer and Matthew Hay- a strong man. Hoggard, meanwhile, restricts Australia of thick cloud that hovered over The Oval any play yesterday after around a quarter den, it gives England an overall lead of 40. offered a reprise of his compelling bowl- all day, reducing the light at times to to four, with 54 overs lost. The sight of Australia, circumstance forcing them to ing that helped to win Tests in Bridgetown sepulchral, they will resume this morn- 23,000 spectators, some of whom have bat in poor light, had been bowled out for and at The Wanderers, with a devastating First Ashes victory for ing, in what promises to be better condi- paid a small fortune for tickets, willing the 367 by Andrew Flintoff’s -

My Autobiography

F SOLID GOLD MY AUTOBIOGRAPHY The Ultimate Rags to Riches Tale Forward by Robin Pilley David Gold, Chairman of Ann Summers, Gold Group International and West Ham United, is a man who has risen from humble and poverty stricken beginnings and achieved a status in life beyond what even he could have ever envisaged. Born an East End Jewish cockney lad, he was at the very bottom of life’s social strata. After a childhood characterised by war, poverty and disease he set out to change his life, and in the process he also changed the lives of everyone close to him. He understands and embraces the importance of change. He also changed the fortunes of his beloved football club, developed an iconic brand in Ann Summers and was influential in liberating the sexual behavior of the great British public. Now, Gold brings his unparalleled ability for change to his inspirational autobiography. This completely reworked edition, ‘The Ultimate Rags to Riches Tale’, focuses more on his personality, his remarkable business achievements, his life- affirming story and his reflections and recollections on a world that changed beyond recognition within his own lifetime. And most importantly, he speaks candidly about how he softened the British stiff upper lip and almost single-handedly brought sex onto the UK’s high streets and changed our sex lives for the better. No one has done more to prove that dreams can come true and now you can read his exceptional autobiography exclusively written to show just 2 what one man can achieve from the most humble beginnings. -

Death in St Jamess Park Free Ebook

FREEDEATH IN ST JAMESS PARK EBOOK Susanna Gregory | 464 pages | 01 Dec 2013 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9780751544336 | English | London, United Kingdom Man arrested on suspicion of murder after body found in London park | UK news | The Guardian With a seating capacity of 52, seats, it is the eighth largest football stadium in England. St James' Park has been the home ground of Newcastle United since and has been used for football since Reluctance to move has led to the distinctive lop-sided appearance of the present-day stadium's asymmetrical stands. Besides club football, St James' Park has also been Death in St Jamess Park for international footballat the Olympics[7] for the rugby league Magic Weekendrugby union World CupPremiership and England Test matches, charity football events, rock concerts, and as a set for Death in St Jamess Park and reality television. The site of St James' Park was originally a patch of sloping grazing land, bordered by Georgian Leazes Terrace, [8] and near the historic Town Moorowned by the Freemen of the city, both factors that later affected development of the ground, with the local council being the landlord of the site. Once the residence of high society in Newcastle, it is now a Grade 1 [9] [10] listed buildingand, recently refurbished, is currently being used as self-catering postgraduate student accommodation by Newcastle University. The first football team to play at St James' Park was Newcastle Rangers in [12] They moved to Death in St Jamess Park ground at Byker inthen returned briefly to St James' Park in before folding that year. -

KT 27-9-2017.Qxp Layout 1

SUBSCRIPTION WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2017 MUHARRAM 7, 1439 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Qatar laborer Mud, misery Concert-goers England drop ‘sacked’ after for refugees arrested for all-rounder speaking to as Bangladesh raising rainbow Stokes after UN team6 tent11 city grows flag32 in Egypt assault14 arrest Kuwait shaves KD 1 Min 25º Max 44º High Tide billion off spending 03:07 & 17:01 Low Tide Economic reforms proving effective • KIA sees 34% growth in 5 years 10:25 & 22:14 32 PAGES NO: 17340 150 FILS By Nawara Fattahova and Faten Omar ing Liquidity Coverage Ratio and Net Stable Funding Ratio. He added that the CBK improved, with banks’ non- KUWAIT: Kuwait’s financial leadership heralded a positive performing loan ratio steadily declining to reach 2.2%, a outlook for the country’s slow growing economy, point- historic low. Also ensured the justified buildup of suffi- ing to a significant reduction in government spending cient provisions; consequently, coverage ratio has and growth in assets under management as key achieve- climbed to a record high of 237%. ments. Kuwait shaved off “more than KD 1 billion in gov- The Central Bank government also called for further ernment expenditure between 2016 and 2017,” said Anas reform: “Progress on many structural fronts is needed; Al-Saleh, Deputy Premier and Finance Minister during the further rationalizing expenditures, increasing non-oil annual Euromoney conference in Kuwait City. revenues, reforming the labor market, increasing the “To reach this result the public financial bodies imple- role of the private sector and in general diversifying the mented measures including adjusting cap and growth economy are some key areas that would continue to rate of public spending and treating the waste in this require unremitting attention.” spending, accelerating the process of collecting late state debts, shifting from the annual budget system to the Investment legislation medium-term budget system, limiting the violations of Kuwait’s parliament is likely to approve a law to the social allowances, and other measures,” he explained. -

Cleland and Dixon 2015 Black and Whiters

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Cleland, Jamie and Dixon, Kevin (2015) ‘Black and whiters’ : the relative powerlessness of ‘active’ supporter organization mobility at English Premier League football clubs. Soccer & Society, 16 (4). pp. 540-544. ISSN 1466-0970 Published by: UNSPECIFIED URL: This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://northumbria-test.eprints- hosting.org/id/eprint/54394/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/pol i cies.html This document may differ from the final, published version of the research and has been made available online in accordance with publisher policies. To read and/or cite from the published version of the research, please visit the publisher’s website (a subscription may be required.) ‘Black and whiters’: The relative powerlessness of ‘active’ supporter organization mobility at English Premier League football clubs This article examines the reaction by Newcastle United supporters to the resignation of Kevin Keegan as Newcastle United manager in September 2008. -

Wales Team Guide Rugby World Cup, Japan Autumn 2019

Wales Team Guide Rugby World Cup, Japan Autumn 2019 celfcreative.com ウェールズ代表チーム @WalesTeamRWC19 wru.wales @WelshRugbyUnion 1 www.wru.co.uk @WelshRugbyUnion Warren’s Last Stand! Whatever happens at the 2019 Rugby World Cup, Welsh rugby is in for a seismic change. After 12 years in charge, Warren Gatland will finally step down as our Head Coach and return to New Zealand. He will go back to his home town of Hamilton with the eternal thanks of everyone connected to rugby in Wales. His achievements during his time in his adopted country have been incredible. Take your pick from three Grand Slams, a record 14 match unbeaten run, 11 victories on the trot in Cardiff or reaching the No 1 status in the World Rankings as his greatest achievement. But one thing is certain, if he can guide Wales And with Alun Wyn Jones driving the team as into a first World Cup final, and even bring our captain we have one of the game’s all- home the Webb Ellis Trophy, then he will eclipse time greats in charge on the field. After three everything else he has achieved during one of tours with the British & Irish Lions, three Grand the greatest international coaching careers. Slams with Wales and now a fourth World Cup, No stone has been left unturned since the he has become the nation’s rugby talisman. 2015 tournament to try to find the winning If everything goes to plan, he will overtake formula to take to Japan. The coach believes his another of Welsh rugby’s golden greats, Gethin side can match any team in the world and our Jenkins, as our leading cap holder in Japan.