Cleland and Dixon 2015 Black and Whiters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read an Extract

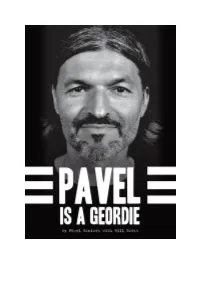

PAVEL IS A GEORDIE Pavel Srnicek Will Scott Contents 1 Pavel’s return 2 Kenny Conflict 3 Budgie crap, crap salad and crap in the bath 4 Dodgy keeper and Kevin who? 5 Got the t-shirt 6 Hooper challenge 7 Cole’s goals gone 8 Second best 9 From Tyne to Wear? 10 Pavel is a bairn 11 Stop or I’ll shoot! 12 Magpie to Owl 13 Italian job 14 Pompey, Portugal and blowing bubbles 15 Country calls 16 Testimonial 17 Slippery slope 18 Best Newcastle team 19 Best international team 20 The Naked Chef 21 Epilogue FOREWORD Spending the first ten years of my football career away from St James’ Park didn’t mean I wasn’t aware of what was going on at my home town club. As a Geordie and a Newcastle United supporter, I always kept a keen interest on what was happening on Tyneside in the early stages of my career at Southampton and Blackburn. Although it was common for clubs to sign foreign players in the early 1990s, the market wasn’t saturated the way it is now, but it was certainly unusual for teams to invest in foreign goalkeepers. And Pavel’s arrival on Tyneside certainly caused a stir. He turned up on the club’s doorstep when it was struggling at the wrong end of the old Second Division. It must have been a baptism of fire for the young Czech goalkeeper. Not only did he have to adapt to a new style of football he had to settle in to a new town and culture. -

'Black and Whiters': the Relative Powerlessness of 'Active' Supporter

‘Black and whiters’: The relative powerlessness of ‘active’ supporter organization mobility at English Premier League football clubs This article examines the reaction by Newcastle United supporters to the resignation of Kevin Keegan as Newcastle United manager in September 2008. Unhappy at the ownership and management structure of the club following Keegan’s departure, a series of supporter-led meetings took place that led to the creation of Newcastle United Supporters’ Club and Newcastle United Supporters’ Trust. This article draws on a non-participant observation of these meetings and argues that although there are an increasing number of ‘active’ supporters throughout English football, ultimately it is the significant number of ‘passive’ supporters who hamper the inclusion of supporters’ organizations at higher-level clubs. The article concludes by suggesting that clubs, irrespective of wealth and success, need to recognize the long-term value of supporters. Failure to do so can result in fan alienation and ultimately decline (as seen with the recent cases of Coventry City and Portsmouth). Keywords: fans; Premier League; supporter clubs; inclusion; mobilization Introduction Over the last twenty years there have been many changes to English football. In this post- Hillsborough era, the most significant change has been the introduction of a Premier League in 1992 and its growing relationship with satellite television (most notably BSkyB). This global exposure has helped increase the number of sponsors and overseas investors and has -

P13 2 Layout 1

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2017 SPORTS Fleetwood to miss British Ex-Newcastle chairman Las Palmas coach Masters for child’s birth Shepherd dies aged 76 Marquez quits NEWCASTLE: Race to Dubai leader Tommy Fleetwood will miss this week’s LONDON: Former Newcastle chairman Freddy Shepherd, a pivotal BARCELONA: Las Palmas coach Manolo Marquez has become the third British Masters in Newcastle for the possible birth of his child, while figure in the club’s 1990s success, has died aged 76, his family La Liga manager to leave his job this season, calling a surprise news con- Andrew Johnston pulled out injured yesterday. Fleetwood, 26, has elected announced yesterday. Shepherd was Newcastle chairman for 10 years ference yesterday to announce his resignation after losing four of the to stay with his partner and manager Clare, who is soon to give birth to the from 1997 and eventually sold his share of the club to current owner first six games of the campaign. Las Palmas are 15th in the standings couple’s child. “I wanted to give myself every chance of play- Mike Ashley. “Freddy Shepherd sadly passed away peacefully at his with six points and Marquez’s last game in charge was a 2-0 ing this week, but being there at the birth of your child is a home last night,” his family said in a statement. “At this difficult time home defeat by Leganes on Sunday. Marquez had never special moment in anyone’s life and I would not want to the family have asked that their privacy be respected.” Tyneside-born coached a top-flight side before landing the job in July miss it,” said Fleetwood. -

Football Talking About Cricket! It’S Never Keep the Ashes

Section:GDN PS PaGe:1 Edition Date:050912 Edition:01 Zone: Sent at 11/9/2005 19:09 cYanmaGentaYellowblack Owen’s crash course Raikkonen rallies Chunder wonder Newcastle striker Spa success keeps Martin Kelner on a faces ugly truth McLaren man in hunt technicolour trend Kevin McCarra, page 10 ≥ Alan Henry, page 13 ≥ Screen Break, page 20 ≥ | 12.09.05 | guardian.co.uk Matthew Hoggard is mobbed after dismissing Adam Gilchrist to start a burst of four for four in 19 balls as England take control at The Oval Tom Shaw/Getty Images England’s day of destiny dawns tumultuous of all series began, was the open-top bus can be dusted down for its tion carved out for Australia by the cen- when the situation demanded and found 23,000 cheer as bad light unthinkable. Helped yesterday by a duvet ride through the city. Bad light prevented turies of Justin Langer and Matthew Hay- a strong man. Hoggard, meanwhile, restricts Australia of thick cloud that hovered over The Oval any play yesterday after around a quarter den, it gives England an overall lead of 40. offered a reprise of his compelling bowl- all day, reducing the light at times to to four, with 54 overs lost. The sight of Australia, circumstance forcing them to ing that helped to win Tests in Bridgetown sepulchral, they will resume this morn- 23,000 spectators, some of whom have bat in poor light, had been bowled out for and at The Wanderers, with a devastating First Ashes victory for ing, in what promises to be better condi- paid a small fortune for tickets, willing the 367 by Andrew Flintoff’s -

My Autobiography

F SOLID GOLD MY AUTOBIOGRAPHY The Ultimate Rags to Riches Tale Forward by Robin Pilley David Gold, Chairman of Ann Summers, Gold Group International and West Ham United, is a man who has risen from humble and poverty stricken beginnings and achieved a status in life beyond what even he could have ever envisaged. Born an East End Jewish cockney lad, he was at the very bottom of life’s social strata. After a childhood characterised by war, poverty and disease he set out to change his life, and in the process he also changed the lives of everyone close to him. He understands and embraces the importance of change. He also changed the fortunes of his beloved football club, developed an iconic brand in Ann Summers and was influential in liberating the sexual behavior of the great British public. Now, Gold brings his unparalleled ability for change to his inspirational autobiography. This completely reworked edition, ‘The Ultimate Rags to Riches Tale’, focuses more on his personality, his remarkable business achievements, his life- affirming story and his reflections and recollections on a world that changed beyond recognition within his own lifetime. And most importantly, he speaks candidly about how he softened the British stiff upper lip and almost single-handedly brought sex onto the UK’s high streets and changed our sex lives for the better. No one has done more to prove that dreams can come true and now you can read his exceptional autobiography exclusively written to show just 2 what one man can achieve from the most humble beginnings. -

Death in St Jamess Park Free Ebook

FREEDEATH IN ST JAMESS PARK EBOOK Susanna Gregory | 464 pages | 01 Dec 2013 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9780751544336 | English | London, United Kingdom Man arrested on suspicion of murder after body found in London park | UK news | The Guardian With a seating capacity of 52, seats, it is the eighth largest football stadium in England. St James' Park has been the home ground of Newcastle United since and has been used for football since Reluctance to move has led to the distinctive lop-sided appearance of the present-day stadium's asymmetrical stands. Besides club football, St James' Park has also been Death in St Jamess Park for international footballat the Olympics[7] for the rugby league Magic Weekendrugby union World CupPremiership and England Test matches, charity football events, rock concerts, and as a set for Death in St Jamess Park and reality television. The site of St James' Park was originally a patch of sloping grazing land, bordered by Georgian Leazes Terrace, [8] and near the historic Town Moorowned by the Freemen of the city, both factors that later affected development of the ground, with the local council being the landlord of the site. Once the residence of high society in Newcastle, it is now a Grade 1 [9] [10] listed buildingand, recently refurbished, is currently being used as self-catering postgraduate student accommodation by Newcastle University. The first football team to play at St James' Park was Newcastle Rangers in [12] They moved to Death in St Jamess Park ground at Byker inthen returned briefly to St James' Park in before folding that year. -

Croft, Charlie ORCID

Croft, Charlie ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9194-2604 (2021) “Different cities, different stories”? Sense of place and its implications for residents’ use of public spaces in the heritage city of York. Doctoral thesis, York St John University. Downloaded from: http://ray.yorksj.ac.uk/id/eprint/5235/ Research at York St John (RaY) is an institutional repository. It supports the principles of open access by making the research outputs of the University available in digital form. Copyright of the items stored in RaY reside with the authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full text items free of charge, and may download a copy for private study or non-commercial research. For further reuse terms, see licence terms governing individual outputs. Institutional Repository Policy Statement RaY Research at the University of York St John For more information please contact RaY at [email protected] “Different cities, different stories”? Sense of place and its implications for residents’ use of public spaces in the heritage city of York. Charlie David John Hugh Croft Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy York St John University Business School January 2021 - 2 - The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material. Any reuse must comply with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and any licence under which this copy is released. © 2021 York St John University and Charlie David John Hugh Croft The right of Charlie David John Hugh Croft to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

KT 27-9-2017.Qxp Layout 1

SUBSCRIPTION WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2017 MUHARRAM 7, 1439 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Qatar laborer Mud, misery Concert-goers England drop ‘sacked’ after for refugees arrested for all-rounder speaking to as Bangladesh raising rainbow Stokes after UN team6 tent11 city grows flag32 in Egypt assault14 arrest Kuwait shaves KD 1 Min 25º Max 44º High Tide billion off spending 03:07 & 17:01 Low Tide Economic reforms proving effective • KIA sees 34% growth in 5 years 10:25 & 22:14 32 PAGES NO: 17340 150 FILS By Nawara Fattahova and Faten Omar ing Liquidity Coverage Ratio and Net Stable Funding Ratio. He added that the CBK improved, with banks’ non- KUWAIT: Kuwait’s financial leadership heralded a positive performing loan ratio steadily declining to reach 2.2%, a outlook for the country’s slow growing economy, point- historic low. Also ensured the justified buildup of suffi- ing to a significant reduction in government spending cient provisions; consequently, coverage ratio has and growth in assets under management as key achieve- climbed to a record high of 237%. ments. Kuwait shaved off “more than KD 1 billion in gov- The Central Bank government also called for further ernment expenditure between 2016 and 2017,” said Anas reform: “Progress on many structural fronts is needed; Al-Saleh, Deputy Premier and Finance Minister during the further rationalizing expenditures, increasing non-oil annual Euromoney conference in Kuwait City. revenues, reforming the labor market, increasing the “To reach this result the public financial bodies imple- role of the private sector and in general diversifying the mented measures including adjusting cap and growth economy are some key areas that would continue to rate of public spending and treating the waste in this require unremitting attention.” spending, accelerating the process of collecting late state debts, shifting from the annual budget system to the Investment legislation medium-term budget system, limiting the violations of Kuwait’s parliament is likely to approve a law to the social allowances, and other measures,” he explained. -

FC DYNAMO KYIV V NEWCASTLE UNITED FC

Matchday One Kyiv 18 September 2002 FC DYNAMO KYIV – NEWCASTLE UNITED FC OLYMPIYSKYI STADIUM, KIEV WEDNESDAY 18 SEPTEMBER 2002 at 21.45 UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE GROUP F, MATCHDAY 1 FC DYNAMO KYIV v NEWCASTLE UNITED FC After the disappointment of failing to progress beyond the first group stage in the last two seasons, FC Dynamo Kyiv open the 2002/03 campaign with high hopes of staying alive in the UEFA Champions League until after the winter break. The season will be the first without Valerii Lobanovskyi at the Ukrainian helm and thus represents the dawn of a new era. The same could also be said of Newcastle United, now back in the UEFA Champions League for the second time after an absence of five years. It allows Bobby Robson to complete a hat-trick, as the former England boss has already competed in the UEFA Champions League with FC Porto and PSV Eindhoven. The match provides a fascinating start to the new campaign, with three crucial points at stake. FC Dynamo Kyiv’s record against English clubs doesn’t generate undue optimism. The Ukrainian club’s only victory in 10 attempts was the 3-1 home win over Arsenal FC in the 1998/99 campaign. The four other home games have produced three draws and the 2-1 defeat by Liverpool FC last season. This is Newcastle United’s second visit to the Ukraine and to Kiev. During their previous campaign in the UEFA Champions League, the Magpies were also drawn into the same group as the Ukrainians and recorded a 2-2 draw when they visited FC Dynamo. -

Financial Viability and Competitive Balance in English Football

Financial Viability and Competitive Balance in English Football by Stephanie Ashley Leach A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London and the Diploma of Imperial College August 2006 Tanaka Business School Imperial College University of London Abstract This thesis empirically examines the importance of competitive balance and how economic objectives and financial viability play a part in its impact on the demand for English football. Previous research in sports economics has been inconclusive in the desirability of competitive balance as well as how economic behaviour may affect its efficacy. Academic opinion is split in its assumptions about whether football clubs act as profit maximisers or utility (win) maximisers, which has a direct consequence on competitive balance and the policies used to promote it. An econometric test of a model of economic objectives in playing performance and revenue generation demonstrates that clubs heavily invest in playing talent to achieve those objectives. The results also show that the commercialisation of football in the 1990s did not appear to affect the achievement of a club's goals, nor did it appear to harm competitive balance. However, the failure to obtain the objectives relative to wage spending and pitch performance do impose a risk on the financial viability of a club and without the proper adjustment mechanisms in place can harm competitive balance. The results also show that clubs demonstrate some evidence of profit maximising behaviour which implies some policies used to promote competitive balance will be ineffective. The optimality of perfect competitive balance itself is questionable and econo- metric tests on match attendance sensitivity to win percentage suggest that a more dispersed distribution of wins would maximise attendance and profits. -

La Ck & W Hite K Nig Ht

HARRY DE COSEMO DE HARRY HARRY DE COSEMO ‘Detailed, insightful and heartwarming, this book captures the very essence of Sir Bobby Robson the manager and, more importantly, the man.’ Black Chris Waugh, The Athletic. Black & White Knight & White Black & White Knight How Sir Bobby Robson Made Newcastle United Again Foreword by George Caulkin Contents Foreword by George Caulkin 7 Acknowledgements 11 Introduction 15 1. Sliding Doors 19 2 The Kindest Man 46 3. Laying The Groundwork 70 4. Reaching The Next Level 93 5. Christmas Number One 118 6 The History Boys 140 7. Magic In Milan 169 8 Cracks Begin To Show 189 9. The Summer Of Discontent 222 10 The Cruellest Cut 242 11. Managing A Team Again 264 Bibliography 285 Chapter 1 Sliding Doors ‘Things were moving at last. The North East was calling me back. I was on my way home’ – Bobby Robson RAIN WAS lashing down hard; the heavens had opened over St James’ Park and finally put out the dwindling fire that was Ruud Gullit’s tenure as manager at Newcastle United The mood was mutinous This famous stadium, sat atop a hill in the city, was a place where dreams almost came true three years earlier Newcastle harnessed the power of unity and, led by Kevin Keegan, a man who understood exactly what it took to guide the club, narrowly missed out on the Premiership title Football is a religion in the area; it can be a force to achieve spectacular things But that was in the past and difficult years followed The whole club had never been so divided in its modern history, and they were only heading one way: down