Human Rights Assessment in Senegal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download.Aspx?Symbolno=CAT/C/SEN/CO/3&Lan G=En>, (Last Consulted April 2015)

SENEGAL: FAILING TO LIVE UP TO ITS PROMISES RECOMMENDATIONS ON THE EVE OF THE AFRICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS’ REVIEW OF SENEGAL 56TH SESSION, APRIL- MAY 2015 Amnesty International Publications First published in 2015 by Amnesty International, West and Central Africa Regional Office Immeuble Seydi Djamil, Avenue Cheikh Anta Diop x 3, rue Frobenius 3e Etage BP. 47582 Dakar, Liberté Sénégal www.amnesty.org © Amnesty International Publications 2015 Index: AFR 49/1464/2015 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................. 4 Follow-up to the 2003 Review....................................................................................... -

Avhandilng Selboe.Pdf (1.284Mb)

Elin Selboe Changing continuities: Multi-activity in the network politics of Colobane, Dakar Dissertation submitted for the PhD degree in Human Geography Faculty of Social Sciences Department of Sociology and Human Geography University of Oslo August 2008 Table of Contents List of acronyms ................................................................................................................... vii Summary ............................................................................................................................... ix Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... xi 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1 Research questions ................................................................................................................. 4 Outline of the dissertation ...................................................................................................... 6 2. Ethnography and fieldwork in Colobane .................................................... 11 Introduction to Senegal, Dakar and Colobane ..................................................................... 11 Researching local political practices through ethnographic fieldwork ................................ 14 The choice of Colobane as the setting for research and fieldwork .................................. 16 Working in the field: participation, observation and conversations/ -

Annual Report Sometimes Brutally

“Human rights defenders have played an irreplaceable role in protecting victims and denouncing abuses. Their commitment Steadfast in Protest has exposed them to the hostility of dictatorships and the most repressive governments. […] This action, which is not only legitimate but essential, is too often hindered or repressed - Annual Report sometimes brutally. […] Much remains to be done, as shown in the 2006 Report [of the Observatory], which, unfortunately, continues to present grave violations aimed at criminalising Observatory for the Protection and imposing abusive restrictions on the activities of human 2006 of Human Rights Defenders rights defenders. […] I congratulate the Observatory and its two founding organisations for this remarkable work […]”. Mr. Kofi Annan Former Secretary General of the United Nations (1997 - 2006) The 2006 Annual Report of the Observatory for the Protection Steadfast in Protest of Human Rights Defenders (OMCT-FIDH) documents acts of Foreword by Kofi Annan repression faced by more than 1,300 defenders and obstacles to - FIDH OMCT freedom of association, in nearly 90 countries around the world. This new edition, which coincides with the tenth anniversary of the Observatory, pays tribute to these women and men who, every day, and often risking their lives, fi ght for law to triumph over arbitrariness. The Observatory is a programme of alert, protection and mobilisation, established by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) in 1997. It aims to establish -

Human Rights in Senegal

HUMAN RIGHTS IN SENEGAL 1 INTRODUCTION Senegal is a country in West Africa and it attained independence from France in 1960. It is located at the westernmost point of the continent and served by multiple breaths of air and maritime travel routes, Senegal is known as the “Gateway to Africa.” The country lies at an ecological boundary where semiarid grassland, oceanfront, and tropical rainforest converge; this diverse environment has endowed Senegal with a wide variety of plant and animal life. It is from this rich natural heritage that the country’s national symbols were chosen: the baobab tree and the lion. The most important city in Senegal is its capital, Dakar. This lively and attractive metropolis which is located on Cape Verde Peninsula along the Atlantic shore is a popular tourist destination (Camara, Clark & Hargreaves 2018). The country is a republic with a president elected to five-year terms. There are more than 80 political parties in Senegal. There is a bicameral parliament with a National Assembly, with 120 seats, and the Senate, with 100 seats. Senegal has an independent judiciary. The highest branches of this are the constitutional court and the court of justice. Senegal is one of the most successful African democracies. The president appoints local administrators. Senegalese religious leaders known as marabouts have strong political influence. In 1994, Senegal began ambitious reforms of the economy with international support. Initially, the currency, the CFA franc, devalued 50 percent and is now linked to the Euro. Price controls have also been dismantled. The reforms helped the economy and GDP grew 5 percent per year from 1995 to 2001. -

Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung

KONRAD ADENAUER STIFTUNG AFRICAN LAW STUDY LIBRARY Volume 12 Edited by Hartmut Hamann, Ibrahima Diallo and Chadidscha Schoepffer Hartmut Hamann is a lawyer specialized in providing legal support for international projects between states and private companies, and in international arbitration proceedings. He is a professor at the Freie Universität Berlin, and at the Chemnitz University of Technology, where he teaches public international law and conflict resolution. His legal and academic activities often take him to Africa. Since 2001 Ibrahima Diallo has been a research assistant specializing in public law at the University Gaston Berger of Saint Louis. He currently teaches public law and his research field is comprised of the following: the constitutions, fundamental rights, the state, decentralization, administrative and constitutional jurisdictions, public commercial law and public finances. He has published several books: the Law of Regional Authorities in Senegal (L’Harmattan 2008) and Landmark Decisions of Senegal’s Constitutional Court (co-author). He has also published several articles: Research on Africa’s Model Constitutional Jurisdiction (AIJC 2005); The Prefect’s future in French Public Law (AJDA December 2006) and the Exception of Illegality within Senegal’s New Judicial System (Revue URED June 2011). Mr. Diallo is also a consultant to several national and international organizations. He advises on issues relating to decentralization and natural, soil and water resource administration. Chadidscha Schoepffer, M.J.I., coordinator of projects and researcher at the International Research Center of Development and Environment at the Justus-Liebig University in Gießen (Germany), is a member of the executive committee of the Association of African Law. -

Periodic Report

REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL ONE PEOPLE – ONE PURPOSE – ONE FAITH PERIODIC REPORT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE AFRICAN CHARTER ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS DES DROITS DE L’HOMME ET DES PEUPLES PRESENTED BY THE REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL April 2013 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS General Introduction CHAPTER 1: SOME ANSWERS TO THE CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS OF THE AFRICAN COMMISSION I. On the Casamance issue II. On the issue of street children III. On prison conditions (a) General information on Senegalese prisons (b) Rehabilitation of prison facilities in Senegal (c) Improving living conditions of detainees (d) New social reintegration policy (e) Improving working and living conditions of prison staff IV. On the issue of creating a conducive environment for the expression of media pluralism and freedom of the press in keeping with the principles of the Charter (a) Constitutional guarantees on the right to information and freedom of expression (b) Constraints (c) Achievements and prospects (1) Draft press code (2) Grant to the media (3) Establishment of cyber journalism in the regions (4) Press Centre (5) Community Radio Stations Support Project (PARCOM) (6) Switching from analogue to digital audiovisual network CHAPTER 2 : OVERVIEW OF GENERAL DATA AND STATISTICS I. Demographic, economic, social and cultural features II. Constitutional and political developments CHAPTER 3 : GENERAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS CHAPTER 4 : PRESENTATION OF THE PREPARATORY PROCESS FOR THIS PERIODIC REPORT CHAPTER 5 : BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE AFRICAN CHARTER IN SENEGAL A. IMPLEMENTATION OF CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS : I. Compliance with rules on non-discrimination (Articles 2 and 3) : 1 II. -

Core Document Forming Part of the Reports of States Parties Senegal

United Nations HRI/CORE/SEN/2011 International Human Rights Distr.: General 19 October 2011 Instruments English Original: French Core document forming part of the reports of States parties Senegal* [15 February 2011] * In accordance with the information transmitted to States parties regarding the processing of their reports, the present document was not edited before being sent to the United Nations translation services. GE.11-46636 (E) 030212 060212 HRI/CORE/SEN/2011 Contents Paragraphs Page I. General data and statistics....................................................................................... 1–28 3 A. Demographic, economic, social and cultural characteristics .......................... 1–21 3 B. Constitutional, political and legal structure .................................................... 22–28 6 II. General framework for the protection and promotion of human rights .................. 29–52 7 A. Acceptance of international human rights norms at the national level ........... 29–33 7 B. Legal framework for the protection and promotion of human rights at the national level......................................................................................... 34–48 9 C. Reporting process for the promotion of human rights at national level.......... 49–52 11 III. Implementation of substantive human rights provisions......................................... 53–78 11 A. Non-discrimination and equality .................................................................... 53–60 11 B. Remedies and procedural safeguards............................................................. -

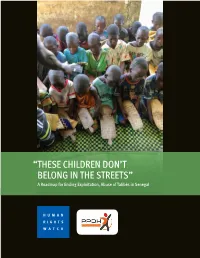

“These Children Don't Belong in the Streets” a Roadmap for Ending Exploitation, Abuse of Talibés in Senegal

“THESE CHILDREN DON’T BELONG IN THE STREETS” A Roadmap for Ending Exploitation, Abuse of Talibés in Senegal HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH “These Children Don't Belong in the Streets” A Roadmap for Ending Exploitation, Abuse of Talibés in Senegal Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-37892 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org DECEMBER 2019 ISBN:978-1-6231-37892 “These Children Don't Belong in the Streets” A Roadmap for Ending Exploitation, Abuse of Talibés in Senegal Map: Locations of Research in Senegal ............................................................................. i Terminology ................................................................................................................... ii Acronyms ..................................................................................................................... -

Bibliography on Islam in Contemporary Sub-Saharan Africa Schrijver, P

Bibliography on Islam in contemporary Sub-Saharan Africa Schrijver, P. Citation Schrijver, P. (2006). Bibliography on Islam in contemporary Sub-Saharan Africa. Leiden: African Studies Centre. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12922 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12922 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Bibliography on Islam in contemporary Sub-Saharan Africa African Studies Centre Research Report 82 / 2006 Bibliography on Islam in contemporary Sub-Saharan Africa Paul Schrijver Published by: African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands Tel. +31 (0)71-527 33 72 Fax: +31 (0)71-527 33 44 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ascleiden.nl Printed by PrintPartners Ipskamp BV, Enschede ISBN-10: 90 5448 067 x ISBN-13: 978 90 5448 067 9 © African Studies Centre, Leiden, 2006 Contents Preface vii I AFRICA (GENERAL) 1 II WEST AFRICA 21 West Africa (General) 21 Benin 32 Burkina Faso 32 Côte d'Ivoire 36 Gambia 39 Ghana 39 Guinea 43 Guinea-Bissau 43 Liberia 44 Mali 45 Mauritania 53 Niger 56 Nigeria 60 Senegal 114 Sierra Leone 139 Togo 141 III WEST CENTRAL AFRICA 143 Angola 143 Cameroon 143 Central African Republic 147 Chad 147 Congo 149 Gabon 150 IV NORTHEAST AFRICA 151 Northeast Africa (General) 151 Eritrea 152 Ethiopia 153 Somalia 156 Sudan 160 v V EAST AFRICA 189 East Africa (General) 189 Burundi 197 Kenya 197 Mozambique 205 Rwanda 206 Tanzania 206 Uganda 212 VI INDIAN -

Presidential Authority and the 2001 Constitution of Senegal Judy Scales-Trent

North Carolina Central Law Review Volume 34 Article 5 Number 1 Volume 34, Number 1 10-1-2011 Presidential Authority and the 2001 Constitution of Senegal Judy Scales-Trent Follow this and additional works at: https://archives.law.nccu.edu/ncclr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Scales-Trent, Judy (2011) "Presidential Authority and the 2001 Constitution of Senegal," North Carolina Central Law Review: Vol. 34 : No. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://archives.law.nccu.edu/ncclr/vol34/iss1/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by History and Scholarship Digital Archives. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Central Law Review by an authorized editor of History and Scholarship Digital Archives. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Scales-Trent: Presidential Authority and the 2001 Constitution of Senegal PRESIDENTIAL AUTHORITY AND THE 2001 CONSTITUTION OF SENEGAL JUDY SCALES-TRENT* ABSTRACT This article begins with a brief introduction to Senegal and a sum- mary of its constitutional history, from the First Constitution in 1960, through the modifications made to the 2001 Constitution. Through these changes we see the radical increase of presidential authority over time. The article then describes Okoth-Ogendo's notion of an "African Paradox," which he describes as a commitment to the notion of a Constitution, but without the classical notion of constitutionalism. Next, it applies Okoth-Ogendo's analytic framework to Senegal to see if that country is part of this "African Paradox." The article concludes by describing the demonstrations and riots that took place in Senegal in June 2011, as the Senegalese reacted with rage to the President's latest proposal to modify the Constitution. -

20Th Activity Report Covers the Period from January to June 2006

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE UNIÃO AFRICANA Addis Ababa, ETHIOPIA P. O. Box 3243 Telephone +251115- 517700 Fax : +251115- 517844 Website : www.africa-union.org EXECUTIVE COUNCIL Ninth Ordinary Session 25 – 29 June 2006 Banjul, THE GAMBIA EX.CL/279 (IX) REPORT OF THE AFRICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS EX.CL/279 (IX) Page 1 TWENTIETH ACTIVITIY REPORT OF THE AFRICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS Section I: Period covered by the Report 1. The 20th Activity Report covers the period from January to June 2006. 2. It is important to recall that the 19th Activity Report of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the African Commission) had been adopted by decision Assembly/AU/DEC.101 (VI) during the 6th Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the African Union held from 23rd to 24th January 2006 in Khartoum, Sudan, after having been considered by the Executive Council. Section II: Holding of the 39th Ordinary Session 3. Since the adoption of the 19th Activity Report in January 2006, the African Commission held a Session, the 39th Ordinary Session, which was held in Banjul, The Gambia, from the 11th to 25th May 2006. The Agenda of the 39th Ordinary Session is attached as Annex One (1) of this Report. 4. The 39th Ordinary Session was preceded by the following meetings: • The NGO Forum, whose objective was to prepare the contribution of the Members of the Commission and that of the partners to the deliberations of the said Session. The NGO Forum was held from 6th to 8th May 2006, in Banjul, The Gambia. -

National Action Plan UNOFFICIAL TRANSLATION

National Action Plan UNOFFICIAL TRANSLATION To cite this National Action Plan, please include the URL and the following information in the citation: Unofficial translation, funded by ARC DP160100212 (CI Shepherd). This National Action Plan was translated into English as part of a research project investigating the formation and implementation of the Women, Peace and Security agenda. This is not an official translation. This research was funded by the Australian Research Council Discovery Project Scheme (grant identifier DP160100212), and managed partly by UNSW Sydney (the University of New South Wales) and partly by the University of Sydney. The project’s chief investigator is Laura J. Shepherd, who is Professor of International Relations at the University of Sydney and Visiting Senior Fellow at the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security. If you have questions about the research, please direct queries by email to [email protected]. Republic of Senegal ***************** Ministry of Gender and Relations with African and Foreign Women’s Associations NATIONAL ACTION PLAN STEERING IMPLEMENTATION OF RESOLUTION 1325 COMMITTEE (2000) OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL OF THE UNITED NATIONS Steering committee for the formulation of the National Action Plan of Senegal for Resolution 1325 (2000) of the Security Council of the United Nations © Ministry of Gender and Relations with African and Foreign Women’s Associations, May 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .......................................... 3 CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 5 CHAPTER II: TERMS OF REFERENCE OF THE STEERING COMMITTEE AND METHODOLOGY ................................................................................. 15 CHAPTER III: SYSTEMIC AND PROSPECTIVE ANALYSIS OF THE CONTEXT IN SENEGAL BY MEANS OF A STUDY OF THE 18 OBJECTIVES AND 26 INDICATORS OF RES.