10Th Century Assyrian Chronology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Hospitals from Antiquity to the Renaissance

Acta Theologica Supplementum 7 2005 THE EVOLUTION OF HOSPITALS FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE RENAISSANCE ABSTRACT There is some evidence that a kind of hospital already existed towards the end of the 2nd millennium BC in ancient Mesopotamia. In India the monastic system created by the Buddhist religion led to institutionalised health care facilities as early as the 5th century BC, and with the spread of Buddhism to the east, nursing facilities, the nature and function of which are not known to us, also appeared in Sri Lanka, China and South East Asia. One would expect to find the origin of the hospital in the modern sense of the word in Greece, the birthplace of rational medicine in the 4th century BC, but the Hippocratic doctors paid house-calls, and the temples of Asclepius were vi- sited for incubation sleep and magico-religious treatment. In Roman times the military and slave hospitals were built for a specialised group and not for the public, and were therefore not precursors of the modern hospital. It is to the Christians that one must turn for the origin of the modern hospital. Hospices, originally called xenodochia, ini- tially built to shelter pilgrims and messengers between various bishops, were under Christian control developed into hospitals in the modern sense of the word. In Rome itself, the first hospital was built in the 4th century AD by a wealthy penitent widow, Fabiola. In the early Middle Ages (6th to 10th century), under the influence of the Be- nedictine Order, an infirmary became an established part of every monastery. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/04/2021 08:59:36AM Via Free Access

Chapter 12 Aristocrats, Mercenaries, Clergymen and Refugees: Deliberate and Forced Mobility of Armenians in the Early Medieval Mediterranean (6th to 11th Century a.d.) Johannes Preiser-Kapeller 1 Introduction Armenian mobility in the early Middle Ages has found some attention in the scholarly community. This is especially true for the migration of individuals and groups towards the Byzantine Empire. A considerable amount of this re- search has focused on the carriers and histories of individual aristocrats or noble families of Armenian origin. The obviously significant share of these in the Byzantine elite has even led to formulations such as Byzantium being a “Greco-Armenian Empire”.1 While, as expected, evidence for the elite stratum is relatively dense, larger scale migration of members of the lower aristocracy (“azat”, within the ranking system of Armenian nobility, see below) or non- aristocrats (“anazat”) can also be traced with regard to the overall movement of groups within the entire Byzantine sphere. In contrast to the nobility, however, the life stories and strategies of individuals of these backgrounds very rarely can be reconstructed based on our evidence. In all cases, the actual signifi- cance of an “Armenian” identity for individuals and groups identified as “Ar- menian” by contemporary sources or modern day scholarship (on the basis of 1 Charanis, “Armenians in the Byzantine Empire”, passim; Charanis, “Transfer of population”; Toumanoff, “Caucasia and Byzantium”, pp. 131–133; Ditten, Ethnische Verschiebungen, pp. 124–127, 134–135; Haldon, “Late Roman Senatorial Elite”, pp. 213–215; Whitby, “Recruitment”, pp. 87–90, 99–101, 106–110; Isaac, “Army in the Late Roman East”, pp. -

Why Did the Import of Dirhams Cease? Viacheslav Kuleshov Institutionen För Arkeologi Och Antikens Kultur Doktorandseminarium 2018-01-31 Kl

Why did the import of dirhams cease? Viacheslav Kuleshov Institutionen för arkeologi och antikens kultur Doktorandseminarium 2018-01-31 Kl. 15-17 1. Introduction The minting of post-reform Islamic silver coins (Kufic dirhams) started under the Umayyad period in 78 AH (697/698). Kufic dirhams were minted using a more or less stable design pattern for more than three centuries until around the middle of the 11th century. The most common are Abbasid and Samanid dirhams of mid-8th to mid- 10th centuries. The later coinages are those of the Buyid, Ziyarid, ‘Uqaylid, Marwanid and Qarakhanid dynasties. 2. Inflows of dirhams under the Abbasid period (750–945), and their silver content The inflow of Kufic dirhams from the Caliphate northwards started as early as around 750. By the beginning of the 9th century the first waves of early Islamic coined silver reached Gotland and Uppland in Sweden, where the oldest grave finds with coins have been discovered. The largest volumes of collected and deposited silver are particularly well recorded in Eastern Europe for the 850s to 860s, 900s to 910s, and 940s to 950s. Of importance is the fact that, as visual examination and many analyses of coins show, from the early 8th to the early 10th centuries an initially established silver content in coins was normally maintained at 92 to 96 per cent. In the first half of the 10th century the same or even higher fineness was typical of the early Samanid dirhams from Central Asia. Such fineness is also evident from colour and metal surface. 3. -

Transcontinental Trade and Economic Growth

M. SHATZMILLER: TRANSCONTINENTAL TRADE AND ECONOMIC GROWTH Transcontinental Trade and Economic Growth in the Early Islamic Empire: The Red Sea Corridor in the 8th-10th Centuries Maya Shatzmiller The question of why and how sustained economic growth the long term, it surely qualifies as a ‘trend’ or a ‘cycle’ occurs in historical societies is most frequently studied in in historical economic growth.7 Several long-term fac- relation to the European model, otherwise known as the tors brought about a series of changes in the key econom- ‘Rise of the West’, the only model to have been studied ic components of the empire: an increase in monetary in detail so far.1 The debate continues over why western supply and circulation; the development and elaboration Europe forged ahead and remained so consistently, while of state fiscal institutions with an efficient system of tax other societies, including eastern Europe, were unable to collection; the creation of legal institutions to uphold stage their own ‘rise’ through intensive growth, maintain property rights; demographic growth resulting from both it consistently once it occurred, or indeed successfully internal population growth and the importing of slaves; emulate the European model. On the other hand, there is a increased output in the manufacturing sector as a result mounting feeling of dissatisfaction with the notion of ex- of increased division of labour; and finally, an increased clusiveness and uniqueness which accompanies the debate volume of trade, efficient markets, commercial techniques about ‘The Rise of the West/Europe’.2 Those who study and development of credit tools. It is the trade component non-Western societies suggest that alternative interpreta- that will concern us here, since it presents us with an ele- tions and comparative studies of economic growth do exist ment that is variable in a comparative context – the ele- and should be looked at, rather than simply accepting the ment being the role of intercontinental trade in economic European model at its face value. -

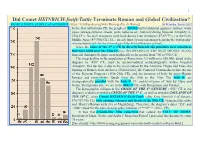

Did Comet HEINRICH-Swift-Tuttle Terminate Roman and Global Civilization? [ROME’S POPULATION CATASTROPHE: G

1 Did Comet HEINRICH-Swift-Tuttle Terminate Roman and Global Civilization? [ROME’S POPULATION CATASTROPHE: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demografia_di_Roma] G. Heinsohn, January 2021 In the first millennium CE, the people of ROME built residential quarters, latrines, water pipes, sewage systems, streets, ports, bakeries etc., but only during Imperial Antiquity (1- 230s CE). No such structures were built during Late Antiquity (4th-6th/7th c.) or the Early Middle Ages (8th-930s CE). [See already https://q-mag.org/gunnar-heinsohn-the-stratigraphy- of-rome-benchmark-for-the-chronology-of-the-first-millennium-ce.html] Since the ruins of the 3rd c. CE lie directly beneath the primitive new structures that were built after the 930s CE (i.e., BEGINNING OF THE HIGH MIDDLE AGES), Imperial Antiquity belongs stratigraphically to the period from 700 to 930s CE. The steep decline in the population of Rome from 1.5 million to 650,000, dated in the diagram to "450" CE, must be accommodated archaeologically within Imperial Antiquity. This decline is due to the crisis caused by the Antonine Plague and Fires, the burning of Rome's State Archives (Tabularium), the Comet of Commodus before the rise of the Severan Emperors (190s-230s CE), and the invasion of Italy by proto-Hunnic Iazyges and proto-Gothic Quadi from the 160s to the 190s. The 160s ff. are stratigraphically parallel with the 450s ff. CE and its invasion of Italy by Huns and Goths. Stratigraphically, we are in the 860s ff. CE, with Hungarians and Vikings. The demographic collapse in the CRISIS OF THE 6th CENTURY (“553” CE in the diagram) is identical with the CRISIS OF THE 3rd C., as well as with the COLLAPSE OF THE 10th C., when Comet HEINRICH-Swift-Tuttle (after King Heinrich I of Saxony; 876/919-936 CE) with ensuing volcanos and floods of the 930s CE ) damaged the globe and Henry’s Roman style city of Magdeburg). -

Medieval Population Dynamics to 1500

Medieval Population Dynamics to 1500 Part C: the major population changes and demographic trends from 1250 to ca. 1520 European Population, 1000 - 1300 • (1) From the ‘Birth of Europe’ in the 10th century, Europe’s population more than doubled: from about 40 million to at least 80 million – and perhaps to as much as 100 million, by 1300 • (2) Since Europe was then very much underpopulated, such demographic growth was entirely positive: Law of Eventually Diminishing Returns • (3) Era of the ‘Commercial Revolution’, in which all sectors of the economy, led by commerce, expanded -- with significant urbanization and rising real incomes. Demographic Crises, 1300 – 1500 • From some time in the early 14th century, Europe’s population not only ceased to grow, but may have begun its long two-century downswing • Evidence of early 14th century decline • (i) Tuscany (Italy): best documented – 30% -40% population decline before the Black Death • (ii) Normandy (NW France) • (iii) Provence (SE France) • (iv) Essex, in East Anglia (eastern England) The Estimated Populations of Later Medieval and Early Modern Europe Estimates by J. C. Russell (red) and Jan de Vries (blue) Population of Florence (Tuscany) Date Estimated Urban Population 1300 120,000 1349 36,000? 1352 41, 600 1390 60,000 1427 37,144 1459 37,369 1469 40,332 1488 42,000 1526 (plague year) 70,000 Evidence of pre-Plague population decline in 14th century ESSEX Population Trends on Essex Manors The Great Famine: Malthusian Crisis? • (1) The ‘Great Famine’ of 1315-22 • (if we include the sheep -

The Tribal Territory of the Kurds Through Arabic Medieval Historiography Boris James

The tribal territory of the Kurds through Arabic medieval historiography Boris James To cite this version: Boris James. The tribal territory of the Kurds through Arabic medieval historiography: Spatial Dynamics, Territorial Categories, and Khaldunian Paradigm. Middle East Studies Association (North America) GatheringPanel : “ Before Nationalism : Land and Loyalty in the Middle East ”, Nov 2007, Montreal, Canada. halshs-00350118 HAL Id: halshs-00350118 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00350118 Submitted on 5 Jan 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. MESA 2007 Panel :Before Nationalism: Land and Loyalty in the Middle East The tribal territory of the Kurds through Arabic medieval historiography: spatial dynamics, territorial categories, and Khaldunian paradigm Boris James (IFPO/ University of Paris 10) In the 14th century an egyptian author, al-Maqrîzî writes : « You should know that nobody agrees on the definition of the Kurds. The ‘Ajam for instance indicate that the Kurds were the favourite food of the king Bayûrasf. He was ordering everyday that two human beings be sacrificed for him so he could consume their flesh. His Vizir Arma’il was sacrificing one and sparing the other who was sent to the mountains of Fârs. -

Coins, Dies, Silver: for a New Approach to the Making of the Feudal Period Jens Christian Moesgaard1,2,4, Guillaume Sarah2, Marc Bompaire2,3

LE STUDIUM Multidisciplinary Journal www.lestudium-ias.com FELLOWSHIP FINAL REPORT Coins, Dies, Silver: for a new approach to the making of the feudal period Jens Christian Moesgaard1,2,4, Guillaume Sarah2, Marc Bompaire2,3 1 Royal Collection of Coins and Medals, National Museum. 1220 Copenhagen, Denmark 2 IRAMAT-CEB, UMR 5060, CNRS/Université d’Orléans, 45000 Orléans, France 3 Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, 75014 Paris, France 4 LE STUDIUM Institute for Advanced Studies, 45000 Orléans, France REPORT INFO ABSTRACT Fellow: Senior researcher Jens The transition in the 10th century from the centralised Carolingian state to Christian MOESGAARD the decentralised feudal principalities is a subject of debate among From National Museum of Denmark historians: was it a violent breakdown or a continuous evolution? The Host laboratory in region Centre-Val major problem facing historians is the scarcity of written sources. But de Loire: IRAMAT-CEB, UMR 5060, coins are numerous and constitute a relevant source material. Indeed, CNRS/Université d’Orléans Host scientist: Dr Marc BOMPAIRE Coinage is an official institution, and studying it informs us about the state Period of residence in region Centre- of society and the organisation of the administration. Val de Loire: September 2017- The study of Norman coinage in the 10th century shows a large and well- September 2018 managed production and a firm control of the circulation. Exchange fees provided income for the duke. This reflects a well-organised stable Keywords: administration and an ability of controlling society, far from the chaotic, Coins, Normandy, 10th century, violent and anarchistic picture of early feudalism that is sometimes managed currency, metal analyses, purported. -

Fleur Devdariani Georgian Miniature: Key Stages of Development in My

Fleur Devdariani Georgian Miniature: Key Stages of Development In my present lecture I will talk about key stages of development of the Georgian miniature. Although this Seasonal School is dedicated to Tao-Klarjeti I decided not to limit myself only to Tao-Klarjeti group of manuscripts but present in general outline the other illuminated codices, which are very important and interesting for the study of the history of art of not only Georgia, but also Byzantium and in general, of the East Christian world. All these handwritten books are created in the different times and therefore they present artistic tasks and peculiarities of their solutions on the different stages of development of the Georgian miniature. All the statements you will hear today are delivered by two prominent Georgian scientists, Rene Shmerling and Gaiane Alibegashvili. I also used the works of the notable Georgian scholar, member of this Kekelidze Center of Manuscripts, Elene Matchavariani. I also want to outline valuable contribution of Nino Kavtaria, young promising scientist of Center of Manuscripts to the study of the manuscripts copied in the scriptorium of the Black Mountain and especially to the research of manuscript of Alaverdi Gospels. According to the surviving evidence, Georgian miniature tradition spans the period from the 9th through the 18th century. Foundation of monasteries as early as the 5th-6th century attests to the role Christianity played in shaping ideology and culturein Georgia. Monasteries, which served as centres of literary activity, contributed to the advancement of Georgian writing and miniature painting. None of the extant manuscripts dated to the period earlier than the 9th century, including 5th-7th century fragmented texts of the palimpsests, is illustrated. -

Chronology Activity Sheet

What Is Chronology Chronology? The skill of putting events into time order is called chronology. History is measured from the first recorded written word about 6,000 years ago and so historians need to have an easy way to place events into order. Anything that happened prior to written records is called ‘prehistory’. To place events into chronological order means to put them in the order in which they happened, with the earliest event at the start and the latest (or most recent) event at the end. Put these events into chronological order from your morning Travelled to school Cleaned teeth 1. 2. 3. 4. Got dressed Woke up 5. 6. Had breakfast Washed my face How do we measure time? There are many ways historians measure time and there are special terms for it. Match up the correct chronological term and what it means. week 1000 years year 10 years decade 365 days century 7 days millennium 100 years What do BC and AD mean? When historians look at time, the centuries are divided between BC and AD. They are separated by the year 0, which is when Jesus Christ was born. Anything that happened before the year 0 is classed as BC (Before Christ) and anything that happened after is classed as AD (Anno Domini – In the year of our Lord). This means we are in the year 2020 AD. BC is also known as BCE and AD as CE. BCE means Before Common Era and CE means Common Era. They are separated by the year 0 just like BC and AD, but are a less religious alternative. -

The Origins of the English Kingdom

ENGLISH KINGDOM The Origins of the English KINGDOMGeorge Molyneaux explores how the realm of the English was formed and asks why it eclipsed an earlier kingship of Britain. UKE WILLIAM of Normandy defeated King King Harold is Old English ones a rice – both words can be translated as Harold at Hastings in 1066 and conquered the killed. Detail ‘kingdom’. The second is that both in 1016 and in 1066 the from the Bayeux English kingdom. This was the second time in 50 Tapestry, late 11th kingdom continued as a political unit, despite the change years that the realm had succumbed to external century. in ruling dynasty. It did not fragment, lose its identity, or Dattack, the first being the Danish king Cnut’s conquest of become subsumed into the other territories of its conquer- 1016. Two points about these conquests are as important as ors. These observations prompt questions. What did this they are easily overlooked. The first is that contemporaries 11th-century English kingdom comprise? How had it come regarded Cnut and William as conquerors not merely of an into being? And how had it become sufficiently robust and expanse of land, but of what Latin texts call a regnum and coherent that it could endure repeated conquest? FEBRUARY 2016 HISTORY TODAY 41 ENGLISH KINGDOM Writers of the 11th century referred to the English kingdom in Latin as the regnum of ‘Anglia’, or, in the vernacular, as the rice of ‘Englaland’. It is clear that these words denoted a territory of broadly similar size and shape to what we think of as ‘England’, distinct from Wales and stretching from the Channel to somewhere north of York. -

Jack Waddell MEDIEVAL ARMS, ARMOR, and TACTICS And

MEDIEVAL ARMS, ARMOR, AND TACTICS And Interactive Qualifying Project Submitted to the faculty Of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Bachelor or Science By Jack Waddell And 7 Brent Palermo Date: December 10th , 2002 Approved: Abstract This project examined and photographed nearly 300 examples of medieval arms and armor in the Higgins Armory collection, and documented the characteristics of armor, weapons, and their associated tactics during the middle ages (approximately 500CE to 1500CE) as well as the historical and technological background against which they were employed. 2 Acknowledgements We would like to thank the Higgins Armory Museum for providing us with access to authentic medieval artifacts and essential research tools. 3 Table of Contents 1. Abstract Vol 1, p 2 2. Acknowledgements 3 3. Table of Contents 4 4. Introduction (By Brent Palermo) 5 5. Historical background of the Middle Ages (By Jack Waddell) 6 a. History 6 b. Feudalism 35 c. War in the Middle Ages 40 d. Medieval Technology 47 6. Armor of the Middle Ages (By Jack Waddell) 55 a. Introduction 55 b. Armor for the Body 57 c. Armor for the Head 69 d. Armor for the Legs 78 e. Armor for the Arms 81 f. Shields 87 g. Snapshots of Armor Ensembles over Time 90 7. Weapons of the Middle Ages (By Brent Palermo) 100 a. Daggers 100 b. Swords 105 c. Axes 112 d. Halberds 115 e. Glaives 116 f. Bills 117 g. Maces 117 h. Morning Stars 118 i. Flails 119 j. War Hammers 120 k.