Twenty Years on the Border

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January / February

CELTIC MUSIC • KENNY HALL • WORLD MUSIC • KIDS MUSIC • MEXICAN PAPER MAKING • CD REVIEWS FREE Volume 3 Number 1 January-February 2003 THE BI-MONTHLY NEWSPAPER ABOUT THE HAPPENINGS IN & AROUND THE GREATER LOS ANGELES FOLK COMMUNITY A Little“Don’t you know that Folk Music Ukulele is illegal in Los Angeles?” — WARREN C ASEYof theWicket Tinkers is A Lot of Fun – a Beginner’s Tale BY MARY PAT COONEY t all started three workshop at UKE-topia hosted by Jim Beloff at years ago when I McCabe’s Guitar Shop in Santa Monica. I was met Joel Eckhaus over my head in about 15 minutes, but I did at the Augusta learn stuff during the rest of the hour – I Heritage Festival just couldn’t execute any of it! But in Elkins, West my fear of chords in any key but I Virginia. The C was conquered. Augusta Heritage The concert that Festival is has been in existence evening was a for over 25 years, and produces delight with an annual 5-week festival of traditional music almost every uke and dance. Each week of the Festival specialist in the explores different styles, including Cajun, SoCal area on the bill. Irish, Old-Time, Blues, Bluegrass. The pro- The theme was old gram also features folk arts and crafts, espe- time gospel, in line with cially those of West Virginia. Fourteen years the subject of Jim’s latest ago Swing Week was instigated by Western book, and the performers that evening had Swing performers Liz Masterson and Sean quite a romp – some playing respectful Blackburn of Denver, CO as a program of gospel, and others playing whatever they music. -

Map of Mae Hong Son & Khun Yuam District Directions

1 ชุดฝึกทักษะการอ่านภาษาอังกฤษเพื่อความเข้าใจ ส าหรับนักเรียนชั้นมัธยมศึกษาปีที่ 4 เรื่อง Welcome to Khun Yuam เล่ม 1 How to Get to Khun Yuam ค าแ นะน าในการใช้ ช ุด ฝ ึ ก ทักษะส าหรั บ ค ร ู เมื่อครูผู้สอนได้น าชุดฝึกทักษะไปใช้ควรปฏิบัติ ดังนี้ 1. ทดสอบความรู้ก่อนเรียน เพอื่ วดั ความรู้พ้นื ฐานของนกั เรียนแตล่ ะคน 2. ดา เนินการจดั กิจกรรมการเรียนการสอน โดยใช้ชุดฝึกทกั ษะการอ่านภาษาองั กฤษเพื่อความ เข้าใจ ควบคูไ่ ปกบั แผนการจดั การเรียนรู้ ช้นั มธั ยมศึกษาปีที่ 4 3. หลงั จากไดศ้ ึกษาเน้ือหาแลว้ ใหน้ กั เรียน ตอบคา ถามเพอื่ ประเมินความรู้แตล่ ะเรื่อง 4. ควรใหน้ กั เรียนปฏิบตั ิกิจกรรมตามชุดฝึกทกั ษะการอ่านภาษาองั กฤษเพื่อความเข้าใจ โดยครูดูแลและใหค้ า แนะนา อยา่ งใกลช้ ิด 5. ใหน้ กั เรียนตรวจสอบคา เฉลยทา้ ยเล่ม เมื่อนกั เรียนทา กิจกรรมตามชุดฝึกทักษะจบแล้วเพื่อ ทราบผลการเรียนรู้ของตนเอง 6. ทดสอบความรู้หลังเรียน หลังจากที่นักเรียนทา ชุดฝึกทักษะจบแล้วด้วยการทาแบบทดสอบ หลังเรียน 7. ใช้เป็นสื่อการสอนสาหรับครู 8. ใช้เป็นแบบเรียนที่ให้นักเรียนได้เรียนรู้ และซ่อมเสริมความรู้ตนเองท้งั ในและนอกเวลาเรียน 2 ชุดฝึกทักษะการอ่านภาษาอังกฤษเพื่อความเข้าใจ ส าหรับนักเรียนชั้นมัธยมศึกษาปีที่ 4 เรื่อง Welcome to Khun Yuam เล่ม 1 How to Get to Khun Yuam คาแ นะน าในการใช้ชุดฝึ กทักษะส าหรับนักเรียน ชุดฝึกทกั ษะการอ่านภาษาองั กฤษเพื่อความเข้าใจ สา หรับนกั เรียนช้นั มธั ยมศึกษาปีที่ 4 เรื่อง Welcome to Khun Yuam เล่ม 1 เรื่อง How to Get to Khun Yuam จานวน 3 ชว่ั โมง คาชี้แจง ใหน้ กั เรียนปฏิบตั ิตามข้นั ตอนดงั น้ี 1. ศึกษารายละเอียดลักษณะของชุดฝึกทกั ษะการอ่านภาษาองั กฤษเพอื่ ความเข้าใจ พร้อม ท้งั ปฏิบตั ิตามข้นั ตอนในแตล่ ะหนา้ 2. นักเรียนทา ชุดฝึกทกั ษะการอ่านภาษาองั -

COVER Feature

COVER FE ATURE 90 PROVINCETOWN ARTS 2016 Over the Years, Listening and Talking, with Marie Howe By Richard McCann About the writing of the poem, she says: Don’t hold back. She says: Write into things. Shine a light into the underlit places. About the writing of the poem, she says: The hard part is getting past the blah blah blah. Past the I think I think I think. Once, one New Year’s Eve in Provincetown, Heidegger, she says. Vorhanden. Objectively pres- maybe in the late 1990s, a bunch of us were back- ent. Present-at-hand. ing back home down Commercial Street in the Over the years, we have made an unintended snow. Mark Doty. Tony Hoagland. Maybe Nick habit of talking about poetry by talking about Flynn. Marie. And me. The snow had started to that snow. fall while we were huddled in a restaurant, laugh- She says: The things of the world don’t need ing and talking. As soon as we stepped out, we our language. Not in order to become more than could feel the winds pick up. The snowstorm was what they already are. turning into a blizzard. I’ve never had a mentor, not as a writer, except We had to link our arms, just so we could make maybe for Tillie Olsen, who used to tell me stories it down the street. from her life. Walking back one night from a lec- Then Tony called out, I know how each of you ture about the stages of grieving, for instance, not would write about this snow. -

Access the Best in Music. a Digital Version of Every Issue, Featuring: Cover Stories

Bulletin YOUR DAILY ENTERTAINMENT NEWS UPDATE MARCH 23, 2020 Page 1 of 27 INSIDE Lil Uzi Vert’s ‘Eternal Atake’ Spends • Roddy Ricch’s Second Week at No. 1 on ‘The Box’ Leads Hot 100 for 11th Week, Billboard 200 Albums Chart Harry Styles’ ‘Adore You’ Hits Top 10 BY KEITH CAULFIELD • What More Can (Or Should) Congress Do Lil Uzi Vert’s Eternal Atake secures a second week No. 1 for its first two frames on the charts dated Dec. to Support the Music at No. 1 on the Billboard 200 albums chart, as the set 28, 2019 and Jan. 4, 2020. Community Amid earned 247,000 equivalent album units in the U.S. in Eternal Atake would have most likely held at No. Coronavirus? the week ending March 19, according to Nielsen Mu- 1 for a second week without the help of its deluxe • Paradigm sic/MRC Data. That’s down just 14% compared to its reissue. Even if the album had declined by 70% in its Implements debut atop the list a week ago with 288,000 units. second week, it still would have ranked ahead of the Layoffs, Paycuts The small second-week decline is owed to the chart’s No. 2 album, Lil Baby’s former No. 1 My Turn Amid Coronavirus album’s surprise reissue on March 13, when a new (77,000 units). The latter set climbs two rungs, despite Shutdown deluxe edition arrived with 14 additional songs, a 27% decline in units for the week.Bad Bunny’s • Cost of expanding upon the original 18-song set. -

Traditions Music Black Secularnon-Blues

TRADITIONS NON-BLUES SECULAR BLACK MUSIC THREE MUSICIANS PLAYING ACCORDION, BONES, AND JAWBONE AT AN OYSTER ROAST, CA. 1890. (Courtesy Archives, Hampton Institute) REV JAN 1976 T & S-178C DR. NO. TA-1418C © BRI Records 1978 NON-BLUES SECULAR BLACK MUSIC been hinted at by commercial discs. John Lomax grass, white and black gospel music, songs for IN VIRGINIA and his son, Alan, two folksong collectors with a children, blues and one anthology, Roots O f The Non-blues secular black music refers to longstanding interest in American folk music, Blues devoted primarily to non-blues secular ballads, dance tunes, and lyric songs performed began this documentation for the Library of black music (Atlantic SD-1348). More of Lomax’s by Afro-Americans. This music is different from Congress in 1933 with a trip to the State recordings from this period are now being issued blues, which is another distinct form of Afro- Penitentiary in Nashville, Tennessee. On subse on New World Records, including Roots Of The American folk music that developed in the deep quent trips to the South between 1934 and 1942, Blues (New World Records NW-252). * South sometime in the 1890s. Blues is character the Lomaxes cut numerous recordings, often at In recent years the emphasis of most field ized by a twelve or eight bar harmonic sequence state prisons, from Texas to Virginia.2 They researchers traveling through the South in search and texts which follow an A-A-B stanza form in found a surprising variety of both Afro-American of Afro-American secular music has been on the twelve bar pattern and an A-B stanza form in and Anglo-American music on their trips and blues, although recorded examples of non-blues the eight bar pattern. -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan. -

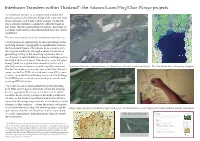

Interbasin Transfers Within Thailand*: the Salween/Luam/Ping/Chao Phraya Projects

Interbasin Transfers within Thailand*: the Salween/Luam/Ping/Chao Phraya projects An interbasin transfer is an engineering scheme that diverts some or all of the discharge from a discrete river basin (or from a sub-basin within a larger catchment) LQWRDVWUHDPGUDLQLQJDFRPSOHWHO\GLͿHUHQWEDVLQRU sub-basin, thereby agumenting the latters’ discharge by a volume equivalent to that diminished from the source catchment. The two main motivations for interbasin transfers are: LQK\GURSRZHUHQJLQHHULQJWRWDNHDGYDQWDJHRIWKH UHFHLYLQJVWUHDPV·WRSRJUDSK\WRVLJQLÀFDQWO\LQFUHDVH the hydrostatic head of the release from a reservoir in the original catchment, through a canal or tunnel to a generating facility in the receiving catchment that is much lower in relative elevation than would be practica- ble within the source basin. The result is a much higher energy yield, for a given dam+reservoir, with only a relatively minor increase in overall capital investment. 7KH6DOZHHQ 7KDQOZLQLQ%XUPHVH HVWXDU\DW0\DZODPD\Q0\DQPDUDQLPDWHGÁ\WKURXJK The Chao Phraya delta at Krungthep (Bangkok) The best example in our study area is the Nam Theun 2 project in the Lao PDR, which diverts some 300 cumecs of water from the Theun-Kading basin into the Xe Bang Fai (XBF) basin, via both excavated new canals and existing XBF tributaries. LQZDWHUUHVRXUFHVPDQDJHPHQWIRUEHWWHUPHHWLQJ both M&I and irrigation demands; where the existing EDVLQ·VDJJUHJDWHGLVFKDUJHLVLQVXFLHQWWRIXOÀO essential needs in dry-season or drought conditions. As seen in the instant case (the Salween-Chao Phraya proposal), the energy requirements of interbasin transfer schemes of this category —where the source catchment is at a lower elevation than the receiving basin may be Oblique space imagery and schematic speed-drDwing of Thanlwin/Salween-Luam-Ping/Chao Phraya interbasin transfer components TXLWHH[WUHPHEXWWKHFRVWEHQHÀWHFRQRPLFVRISXPSLQJ Coordinates: 17°4955N 97°4131E Yuam River From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia vs. -

Project Gutenberg Etext of 20 Years at Hull House by Jane Addams

TWENTY YEARS AT HULL-HOUSE WITH AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL NOTES BY JANE ADDAMS CONTENTS Preface I. EARLIEST IMPRESSIONS II. INFLUENCE OF LINCOLN III. BOARDING-SCHOOL IDEALS IV. THE SNARE OF PREPARATION V. FIRST DAYS AT HULL-HOUSE VI. THE SUBJECTIVE NECESSITY FOR SOCIAL SETTLEMENTS VII. SOME EARLY UNDERTAKINGS AT HULL-HOUSE VIII. PROBLEMS OF POVERTY IX. A DECADE OF ECONOMIC DISCUSSION X. PIONEER LABOR LEGISLATION IN ILLINOIS XI. IMMIGRANTS AND THEIR CHILDREN XII. TOLSTOYISM XIII. PUBLIC ACTIVITIES AND INVESTIGATIONS XIV. CIVIC COOPERATION 1 XV. THE VALUE OF SOCIAL CLUBS XVI. ARTS AT HULL-HOUSE XVII. ECHOES OF THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION XVIII. SOCIALIZED EDUCATION Selected Bibliography Index TO THE MEMORY OF MY FATHER PREFACE [She was, the British labor leader John Burns said, “the only saint America had produced.” It was as Saint Jane that she was known to millions around the earth and none now will challenge her right to that name. —Henry Steele Commager Amherst, Mass.] [Every preface is, I imagine, written after the book has been completed and now that I have finished this volume I will state several difficulties which may put the reader upon his guard unless he too postpones the preface to the very last.] […]Many times during the writing of these reminiscences, I have become convinced that the task was undertaken all too soon. One’s fiftieth year is indeed an impressive milestone at which one may well pause to take an accounting[….][, but the people with whom I have so long journeyed 2 have] become so intimate a part of my lot that they cannot be -

Reconsidering Diasporic Literature: "Homeland" and "Otherness" in the Lost Daughter of Happiness

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses October 2019 Reconsidering Diasporic Literature: "Homeland" and "Otherness" in The Lost Daughter of Happiness Qijun Zhou University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Chinese Studies Commons Recommended Citation Zhou, Qijun, "Reconsidering Diasporic Literature: "Homeland" and "Otherness" in The Lost Daughter of Happiness" (2019). Masters Theses. 866. https://doi.org/10.7275/14922477 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/866 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECONSIDERING DIASPORIC LITERATURE: “HOMELAND” AND “OTHERNESS” IN THE LOST DAUGHTER OF HAPPINESS A Thesis Presented by QIJUN ZHOU Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS September 2019 Chinese East Asian Languages and Cultures © Copyright by Qijun Zhou 2019 All Rights Reserved RECONSIDERING DIASPORIC LITERATURE: “HOMELAND” AND “OTHERNESS” IN THE LOST DAUGHTER OF HAPPINESS A Thesis Presented by QIJUN ZHOU Approved as to style and content by: ___________________________________________ Enhua Zhang, Chair -

Kenny Rogers Twenty Years Ago Mp3, Flac, Wma

Kenny Rogers Twenty Years Ago mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop Album: Twenty Years Ago Country: Spain Released: 1987 Style: Ballad MP3 version RAR size: 1192 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1712 mb WMA version RAR size: 1292 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 581 Other Formats: AIFF DXD XM ASF MIDI AA AU Tracklist Hide Credits Twenty Years Ago A Producer, Arranged By – Jay Graydon, Kenny MimsWritten-By – Dan Tyler , Michael Noble, 3:48 Michael Spriggs, Wood Newton The Heart Of The Matter B 4:35 Producer, Arranged By – George MartinWritten-By – Micheal Smotherman Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – RCA/Ariola International Distributed By – RCA/Ariola-Ariola/RCA Distributed By – RCA S.A. Manufactured By – RCA S.A. Printed By – Indugraf Madrid, S.A. Credits Design – Spiral Studio Producer – George Martin, Jay Graydon Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout: PB 49775-A Matrix / Runout: PB 49775-B Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year PB 41387, Kenny Twenty Years Ago RCA, PB 41387, Europe 1987 DSB-8415 Rogers (7") RCA DSB-8415 Kenny Twenty Years Ago 5078-7-R RCA 5078-7-R US 1987 Rogers (7", Single) 5078-7-RAA, Kenny Twenty Years Ago RCA, 5078-7-RAA, US 1987 5078-7-R Rogers (7", Promo) RCA 5078-7-R Kenny Twenty Years Ago 104651 RCA 104651 Australia 1987 Rogers (7", Single) 5078-7-RAA, Kenny Twenty Years Ago RCA, 5078-7-RAA, US 1987 5078-7-R Rogers (7", Single, Promo) RCA 5078-7-R Related Music albums to Twenty Years Ago by Kenny Rogers Kenny Rogers - Love Collection Other Kenny Rogers - Morning -

A Christmas Memory

Imagine a morning in late November. A coming of winter morning more than twenty years ago. Consider the kitchen of a spreading old house in a country town. A great black stove is its main feature; but there is also a big round table and a fireplace with two rocking chairs placed in front of it. Just today the fireplace commenced its seasonal roar. A woman with shorn white hair is standing at the kitchen window. She is wearing tennis shoes and a shapeless gray sweater over a summery calico dress. She is small and sprightly, like a bantam hen; but, due to a long youthful illness, her shoulders are pitifully hunched. Her face is remarkable—not unlike Lincoln's, craggy like that, and tinted by sun and wind; but it is delicate too, finely boned, and her eyes are sherry-colored and timid. "Oh my," she exclaims, her breath smoking the windowpane, "it's fruitcake weather!" The person to whom she is speaking is myself. I am seven; she is sixty-something, We are cousins, very distant ones, and we have lived together—well, as long as I can remember. Other people inhabit the house, relatives; and though they have power over us, and frequently make us cry, we are not, on the whole, too much aware of them. We are each other's best friend. She calls me Buddy, in memory of a boy who was formerly her best friend. The other Buddy died in the 1880's, when she was still a child. She is still a child. -

Knowing the Salween River: Resource Politics of a Contested Transboundary River the Anthropocene: Politik—Economics— Society—Science

The Anthropocene: Politik—Economics—Society—Science Carl Middleton Vanessa Lamb Editors Knowing the Salween River: Resource Politics of a Contested Transboundary River The Anthropocene: Politik—Economics— Society—Science Volume 27 Series Editor Hans Günter Brauch, Peace Research and European Security Studies (AFES-PRESS), Mosbach, Baden-Württemberg, Germany More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15232 http://www.afes-press-books.de/html/APESS.htm http://www.afes-press-books.de/html/APESS_27.htm# Carl Middleton • Vanessa Lamb Editors Knowing the Salween River: Resource Politics of a Contested Transboundary River Editors Carl Middleton Vanessa Lamb Center of Excellence for Resource School of Geography Politics in Social Development, University of Melbourne Center for Social Development Studies, Melbourne, VIC, Australia Faculty of Political Science Chulalongkorn University Bangkok, Thailand ISSN 2367-4024 ISSN 2367-4032 (electronic) The Anthropocene: Politik—Economics—Society—Science ISBN 978-3-319-77439-8 ISBN 978-3-319-77440-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77440-4 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adap- tation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material.