A Practicurn Submifted in Partial Fuifilment of the Requirernents for the Degree, Master of Natural Resource Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thistle Indian-Trader.Pdf

THE UNIVERS]TY OF MANITOBA INDIAN--TRADER RELATIONS: AN ETHNOH]STORY OF WESTERN WOODS CREE.-HUDSONIS BAY COMPANY TRADER CONTACT IN THE CUMBERLAND HOUSE--THE PAS REGION TO 1840 A thesis subnitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirenents for the degree of Master of Art s in the Indívidual Tnterdisciplinary Programne (Anthropology, History, Educat i on) by Paul Clifford Thistle .Tu 1v 19 8 3 INDIAN--TRADDR REI-ATIONS: AN ETHNOII ISTORY 0F I¡]ESTERN WOODS CREE--HUDSONTS BAY COMPANY TRADER CONTACT IN THE CUMBERLAND HOUSE--THE PAS REGION TO I84O by PauI Cl ifford Thistle A tlìesis submitted to the Faculty of G¡aduate Studies ol the University of Manitobâ in partial fulfillment of the requirenìer.ìts of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS @ 1983 Pe¡missjon has been granted to the LIBRARY OF THE UNIVER- SITY OF MANITOBA to lend or sell copies of this thesis. to the NATIONAL LIBRARY OF CANADA to microfilnr this thesis and to lend or sell copies of the film, and UNIVERSITy MICROFILMS to publish an abstract of this thesis. The author reserves other publication rights, and neither the thesis nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or other- wise reproduced without the autho¡'s w¡ittelr perurissiotr. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT vl1 CHAPTER I ]NTRODUCT ION 1 The Prob 1em 1 Purpose 3 Scope 4 S igni ficance 5 Method 11 The o ry T4 (i) Ethnic/Race Relations Theory 16 (ii) Ethnicity Theory 19 (iii) Culture Change and Acculturat i on Theory 22 Sumrnary Discussion 26 II ETHNOGRAPHY OF THE RELATION z8 Introduction . -

The Quest for the Northwest Passage

NOVA DANIA THE QUEST FOR THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE SUZANNE CARLSON With considerable envy, the seventeenth century King of Denmark, Christian IV, watched the scramble to discover the elusive passage over Polar regions to lay claim to the riches of Cathay. This article will follow the fate of Christian’s early seventeenth century New World foothold, Nova Dania, through the cartographic record, speculating on what and when the Danes might have known about the then frozen northwest passage. An essential piece in this story is the amazing tale of Jens Munk, a merchant adventurer in the King’s service. For the cyber traveler, opportunities have reached a new zenith with Google Earth (FIGURE 1). I find myself cruising at 35,000 feet over the Alps, the Arabian Desert, up the Dania Nova Amazon, and to one of my favorite armchair destinations, FIGURE 2. JUSTUS DANCKERT’S TOTIUS AMERICAE DESCRIPTIO, the Arctic. With your AMSTERDAM, CA. 1680. VESTERGOTLANDS MUSEET, GOTHENBURG, SWEDEN Google joy stick, PART I - MAPPING NOVA DANIA you are able to glide with ease through the newly open waters With addictive zeal I searched map after map until I finally of the Northwest spotted it again: this time with the name reversed into Nova Passage. Dania (New Denmark). And there was more. Mer Cristian, Mare Christianum, or Christians Sea, depending on the Before the days of FIGURE 1. NORTHERN CANADA AND language appeared in what is now Fox Basin. Later, Nova GREENLAND. GOOGLE EARTH, 2006 satellite imaging, we Dania abandoned its Latin pretensions and became Nouvelle were content with and Denmarque and, as time went on, its location began to fascinated by maps, maps of unknown exotic places, maps wander—north into Buttons Bay, west into the interior, and showing nations or would-be empires. -

Our Northern Waters; a Report Regarding Hudson's Bay and Straits

MKT MM W A REPORT PRESENTED TO FJT2 V/IN.NIPE6 B0HRD OF WDE REGARDING THE Hudson's Bay # Straits in Minerals, Fisheries, Timber, Furs, /;,;„,/ r, Statment of their Hesources Navigation of them Uamt end other products. A/so Notes on the Meteoro- waters, together with Historical Events and logical and Climatic Data. 35 CHARLES N. BELL. vu yiJeni Manitoba Historical and Scientific Society F5012 1884 B433 Bight of Canada, in the year One Thousand [tere'd according to Act of the Parliament Ofiice of the Minister Hundred and Eighty-four, by Charles Napier Bell, in the of Agriculture. Published by authority of the TIPfc-A-IDE- -WlllSrilSI IPEG BOAED OF Jambs E. Steen, 1'rinter, Winnipeg. The EDITH and LORNE PIERCE COLLECTION of CANADIANA Queen's University at Kingston tihQjl>\hOJ. W OUR NORTHERN WATERS; A REPORT PRESENTED TO THE WINNIPEG BOARD OF TRADE REGARDING THE Hudson's Bay and Straits Being a Statement of their Resources in Minerals, Fisheries, Timber, Fur Game and other products. Also Notes on the Navigation of these waters, together with Historical Events and Meteoro- logical and Climatic Data. By CHARLES N. BELL. Published by authority of the "WHSrUSTIiE'IEG- BOAED OIF TEADE. Jaairs E. Stben, Printer, Winnipeg. —.. M -ol^x TO THE President and Members of Winnipeg Board of Trade. Gentlemen : As requested by you some time ago, I have compiled and present herewith, what information I have been enabled to obtain regarding our Northern Waters. In my leisure hours, at intervals during the past five years, I have as a matter of interest collected many books, reports, etc., bearing on this subject, and I have to say that every statement made in this report is supported by competent authorities, and when it is possible I give them as a reference. -

Lt. Aemilius Simpson's Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826

The Journal of the Hakluyt Society August 2014 Lt. Aemilius Simpson’s Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826 Edited by William Barr1 and Larry Green CONTENTS PREFACE The journal 2 Editorial practices 3 INTRODUCTION The man, the project, its background and its implementation 4 JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE ACROSS THE CONTINENT OF NORTH AMERICA IN 1826 York Factory to Norway House 11 Norway House to Carlton House 19 Carlton House to Fort Edmonton 27 Fort Edmonton to Boat Encampment, Columbia River 42 Boat Encampment to Fort Vancouver 62 AFTERWORD Aemilius Simpson and the Northwest coast 1826–1831 81 APPENDIX I Biographical sketches 90 APPENDIX II Table of distances in statute miles from York Factory 100 BIBLIOGRAPHY 101 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Fig. 1. George Simpson, 1857 3 Fig. 2. York Factory 1853 4 Fig. 3. Artist’s impression of George Simpson, approaching a post in his personal North canoe 5 Fig. 4. Fort Vancouver ca.1854 78 LIST OF MAPS Map 1. York Factory to the Forks of the Saskatchewan River 7 Map 2. Carlton House to Boat Encampment 27 Map 3. Jasper to Fort Vancouver 65 1 Senior Research Associate, Arctic Institute of North America, University of Calgary, Calgary AB T2N 1N4 Canada. 2 PREFACE The Journal The journal presented here2 is transcribed from the original manuscript written in Aemilius Simpson’s hand. It is fifty folios in length in a bound volume of ninety folios, the final forty folios being blank. Each page measures 12.8 inches by seven inches and is lined with thirty- five faint, horizontal blue-grey lines. -

Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area Definitions for the Period 2002 to 2012

Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area Definitions for the period 2002 to 2012 The following list identifies the RHAs and RHA Districts in Manitoba between the period 2002 and 2012. The 11 RHAs are listed using major headings with numbers and include the MCHP - Manitoba Health codes that identify them. RHA Districts are listed under the RHA heading and include the Municipal codes that identify them. Changes / modifications to these definitions and the use of postal codes in definitions are noted where relevant. 1. CENTRAL (A - 40) Note: In the fall of 2002, Central changed their districts, going from 8 to 9 districts. The changes are noted below, beside the appropriate district area. Seven Regions (A1S) (* 2002 changed code from A8 to A1S *) '063' - Lakeview RM '166' - Westbourne RM '167' - Gladstone Town '206' - Alonsa RM 'A18' - Sandy Bay FN Cartier/SFX (A1C) (* 2002 changed name from MacDonald/Cartier, and code from A4 to A1C *) '021' - Cartier RM '321' - Headingley RM '127' - St. Francois Xavier RM Portage (A1P) (* 2002 changed code from A7 to A1P *) '090' - Macgregor Village '089' - North Norfolk RM (* 2002 added area from Seven Regions district *) '098' - Portage La Prairie RM '099' - Portage La Prairie City 'A33' - Dakota Tipi FN 'A05' - Dakota Plains FN 'A04' - Long Plain FN Carman (A2C) (* 2002 changed code from A2 to A2C *) '034' - Carman Town '033' - Dufferin RM '053' - Grey RM '112' - Roland RM '195' - St. Claude Village '158' - Thompson RM 1 Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area -

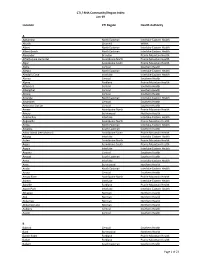

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19 Location CTI Region Health Authority A Aghaming North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Akudik Churchill WRHA Albert North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Albert Beach North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Alexander Brandon Prairie Mountain Health Alfretta (see Hamiota) Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Algar Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Alpha Central Southern Health Allegra North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Almdal's Cove Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Alonsa Central Southern Health Alpine Parkland Prairie Mountain Health Altamont Central Southern Health Albergthal Central Southern Health Altona Central Southern Health Amanda North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Amaranth Central Southern Health Ambroise Station Central Southern Health Ameer Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Amery Burntwood Northern Health Anama Bay Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Angusville Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arbakka South Eastman Southern Health Arbor Island (see Morton) Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Arborg Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arden Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Argue Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Argyle Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arizona Central Southern Health Amaud South Eastman Southern Health Ames Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Amot Burntwood Northern Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arona Central Southern Health Arrow River Assiniboine -

Keeyask Generation Project April 2014

REPORT ON PUBLIC HEARING Keeyask Generation Project April 2014 REPORT ON PUBLIC HEARING Keeyask Generation Project April 2014 ii iii iv Table of Contents Foreword . xi Executive Summary . xv Chapter One: Introduction. .1 1.1 Th e Manitoba Clean Environment Commission. .1 1.2 Th e Project . .1 1.3 Th e Proponent. .2 1.4 Terms of Reference . .3 1.5 Th e Hearings . .4 1.6 Th e Report. .4 Chapter Two: The Licensing Process . .7 2.1 Needed Licences and Approvals . .7 2.2 Review Process for an Environment Act Licence . .7 2.3 Federal Regulatory Review and Decision Making . .8 2.4 Section 35 of Canada’s Constitution. .8 2.5 Need For and Alternatives To. .9 2.6 Role of the Clean Environment Commission . .9 2.7 Th e Licensing Decision. .9 Chapter Three: The Public Hearing Process. 11 3.1 Clean Environment Commission . 11 3.2 Public Participation . 11 3.2.1 Participants . 11 3.2.2 Participant Assistance Program . 11 3.2.3 Presenters. 12 3.3 Th e Pre-Hearing . 12 3.4 Th e Hearings . 12 v Chapter Four: Manitoba’s Electrical Generation and Transmission System . 13 4.1 System Overview. 13 4.2 Generating Stations . 15 4.3 Lake Winnipeg Regulation and the Churchill River Diversion. 17 Chapter Five: The Keeyask Generation Project. 21 5.1 Overview. 21 5.2 Major Project Components and Infrastructure. 23 5.2.1 Powerhouse . 23 5.2.2 Spillway . 24 5.2.3 Dams . 24 5.2.4 Dykes . 24 5.2.5 Ice Boom . -

1 Métis Fur Trade Employees, Free Traders, Guides and Scouts

Métis Fur Trade Employees, Free Traders, Guides and Scouts – Darren R. Préfontaine, Patrick Young, Todd Paquin and Leah Dorion Module Objective: In this module, the students will learn about the Métis’ role in the fur trade, their role as free traders, and their role as guides and scouts – positions, which contributed immensely to the development of Canada. These various economic activities contributed to the Métis worldview since many Métis remained loyal fur trade employees, while others desired to live and make an independent living for themselves and their families. They will also learn that the Métis comprised a large and distinct element within the fur trade in which they played a number of key and essential roles. The students will also appreciate that while the Métis were largely a product of the fur trade, they gradually became their own people and resisted attempts to be controlled or manipulated by outside economic forces. Finally, the students will also learn that the Métis' knowledge of the country and of First Nations languages and customs made them superb guides, scouts, and interpreters. As Metis Elder Madeline Bird explains it, the Metis are mediators, forming a bridge between conflicting actions, dogmas, and beliefs. They emerged as geographers of experience and persuasion, mastering competing situations to the benefit of both land and isolated cultures – serving as trailblazers, middlemen, interpreters, negotiators and constitutional arbitrators1. Métis Labour in the Fur Trade The Métis played perhaps the most important role in the fur trade because they were the human links between First Nations and Europeans. The Métis were employed in every facet of the fur trade and this fact alone ensured that they would remain tied to the fortunes of a trade, which was outside their control. -

Exploring the Canoe in Canadian Experience, by James Raffan

318 • REVIEWS accounts, becomes a man who married for money and, when POWELL, T. 1961. The long rescue. London: W.H. Allen. it ran out, abandoned his wife to join the army. William Cross, TODD, A.L. 1961. Abandoned. New York: McGraw-Hill Book the alcoholic engineer who was the first to die, acquires Company. character through his gruff journal entries, usually colorful knocks at Greely, whom he labeled “Old Stubbornness” or Jerry Kobalenko “STN (our shirt-tail navigator)” (p. 157, 173). PO Box 1286 Guttridge’s fairness and the depth of his historical Banff, Alberta, Canada research are striking. If there is a drawback to Ghosts of T0L 0C0 Cape Sabine, it is that the 80-year-old author has no [email protected] personal experience with the Arctic he writes about and thus makes many small errors. Dutch Island lies within a few metres of mainland Ellesmere, not two miles offshore; BARK, SKIN, AND CEDAR: EXPLORING THE CA- the photo caption of Pim Island misidentifies Cape Sabine; NOE IN CANADIAN EXPERIENCE. By JAMES and contrary to what Greely himself believed, the small RAFFAN. Toronto: HarperCollins Publishers Ltd., 1999. seabirds the party hunted at Camp Clay were not dovekies: ISBN 0-00-638653-9. xiv + 274 p., maps, b&w illus., they were guillemots. More importantly, the author over- notes, index. Softbound. Cdn$19.95. looks key issues in the tragedy because of his lack of familiarity with the area. In February 1884, when Sergeant Bark, Skin, and Cedar will surely make for informative Rice and the Greenland native Jens Edward tried to cross and inspirational reading for housebound canoe enthusi- Smith Sound to reach Greenland for help, they were asts this year. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Section M: Community Support

Section M: Community Support Page 251 of 653 Community Support Health Canada’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services has developed the Children’s Services Reference Chart for general information on what types of health services are available in the First Nations’ communities. Colour coding was used to indicate where similar services might be accessible from the various community programs. A legend that explains each of the colours /categories can be found in the centre of chart. By using the chart’s colour coding system, resource teachers may be able to contact the communities’ agencies and begin to open new lines of communication in order to create opportunities for cost sharing for special needs services with the schools. However, it needs to be noted that not all First Nations’ communities offer the depth or variety of the services described due to many factors (i.e., budgets). Unfortunately, there are times when special needs services are required but cannot be accessed for reasons beyond the school and community. It is then that resource teachers should contact Manitoba’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services to ask for direction and assistance in resolving the issue. Manitoba’s Regional Advisor, Children’s Special Services, First Nations and Inuit Health Programs is Mary L. Brown. Phone: 204-‐983-‐1613 Fax: 204-‐983-‐0079 Email: [email protected] On page two is the Children’s Services Reference Chart and on the following page is information from the chart in a clearer and more readable format including -

Large Area Planning in the Nelson-Churchill River Basin (NCRB): Laying a Foundation in Northern Manitoba

Large Area Planning in the Nelson-Churchill River Basin (NCRB): Laying a foundation in northern Manitoba Karla Zubrycki Dimple Roy Hisham Osman Kimberly Lewtas Geoffrey Gunn Richard Grosshans © 2014 The International Institute for Sustainable Development © 2016 International Institute for Sustainable Development | IISD.org November 2016 Large Area Planning in the Nelson-Churchill River Basin (NCRB): Laying a foundation in northern Manitoba © 2016 International Institute for Sustainable Development Published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development International Institute for Sustainable Development The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) is one Head Office of the world’s leading centres of research and innovation. The Institute provides practical solutions to the growing challenges and opportunities of 111 Lombard Avenue, Suite 325 integrating environmental and social priorities with economic development. Winnipeg, Manitoba We report on international negotiations and share knowledge gained Canada R3B 0T4 through collaborative projects, resulting in more rigorous research, stronger global networks, and better engagement among researchers, citizens, Tel: +1 (204) 958-7700 businesses and policy-makers. Website: www.iisd.org Twitter: @IISD_news IISD is registered as a charitable organization in Canada and has 501(c)(3) status in the United States. IISD receives core operating support from the Government of Canada, provided through the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and from the Province