The Fatality Inquiries Act and in the Matter Of: Susan Capelia Redhead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COUNCIL Agenda

ST JOHN’S COLLEGE COUNCIL Agenda For the Meeting of January 24, 2018 Meal at 5:30, Meeting from 6:00 Room 108, St John’s College 1. Opening Prayer 2. Approval of the Agenda 3. Approval of the November 22, 2017 Minutes 4. Business arising from the Minutes 5. New Business a) Set the budget parameters for the upcoming fiscal year b) Bequest from the estate of Dorothy May Hayward c) Appointment of Architectural firm to design the new residence d) Approval of the Sketch Design Offer of Services for the new residence e) Development Committee f) Call for Honorary Degree Nominations 6. Reports from Committees, College Officers and Student Council a) Reports from Committees – Council Executive, Development, Finance & Admin. b) Report from Assembly c) Reports from College Officers and Student Council i) Warden ii) Dean of Studies iii) Development Office iv) Dean of Residence v) Spiritual Advisor vi) Bursar vii) Registrar viii) Senior Stick 7. Other Business 8. Adjournment ST JOHN’S COLLEGE COUNCIL MINUTES For the Meeting of November 22, 2017 Meal at 5:30, Meeting from 6:00 Room 108, St John’s College Present: D. Watt, G. Bak, P. Cloutier (Chair), J. McConnell, H. Richardson, J. Ripley, J. Markstrom, I. Froese, P. Brass, C. Trott, C. Loewen, J. James, S. Peters (Secretary) Regrets: D. Phillips, B. Pope, A. Braid, E. Jones, E. Alexandrin 1. Opening Prayer C. Trott opened the meeting with prayer. 2. Approval of the Agenda MOTION: That the agenda be approved as distributed. D. Watt / J. McConnell CARRIED 3. Approval of the September 27, 2017 Minutes MOTION: That the minutes of the meeting of September 27, 2017 be approved as distributed. -

Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area Definitions for the Period 2002 to 2012

Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area Definitions for the period 2002 to 2012 The following list identifies the RHAs and RHA Districts in Manitoba between the period 2002 and 2012. The 11 RHAs are listed using major headings with numbers and include the MCHP - Manitoba Health codes that identify them. RHA Districts are listed under the RHA heading and include the Municipal codes that identify them. Changes / modifications to these definitions and the use of postal codes in definitions are noted where relevant. 1. CENTRAL (A - 40) Note: In the fall of 2002, Central changed their districts, going from 8 to 9 districts. The changes are noted below, beside the appropriate district area. Seven Regions (A1S) (* 2002 changed code from A8 to A1S *) '063' - Lakeview RM '166' - Westbourne RM '167' - Gladstone Town '206' - Alonsa RM 'A18' - Sandy Bay FN Cartier/SFX (A1C) (* 2002 changed name from MacDonald/Cartier, and code from A4 to A1C *) '021' - Cartier RM '321' - Headingley RM '127' - St. Francois Xavier RM Portage (A1P) (* 2002 changed code from A7 to A1P *) '090' - Macgregor Village '089' - North Norfolk RM (* 2002 added area from Seven Regions district *) '098' - Portage La Prairie RM '099' - Portage La Prairie City 'A33' - Dakota Tipi FN 'A05' - Dakota Plains FN 'A04' - Long Plain FN Carman (A2C) (* 2002 changed code from A2 to A2C *) '034' - Carman Town '033' - Dufferin RM '053' - Grey RM '112' - Roland RM '195' - St. Claude Village '158' - Thompson RM 1 Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area -

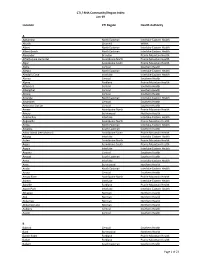

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19 Location CTI Region Health Authority A Aghaming North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Akudik Churchill WRHA Albert North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Albert Beach North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Alexander Brandon Prairie Mountain Health Alfretta (see Hamiota) Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Algar Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Alpha Central Southern Health Allegra North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Almdal's Cove Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Alonsa Central Southern Health Alpine Parkland Prairie Mountain Health Altamont Central Southern Health Albergthal Central Southern Health Altona Central Southern Health Amanda North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Amaranth Central Southern Health Ambroise Station Central Southern Health Ameer Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Amery Burntwood Northern Health Anama Bay Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Angusville Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arbakka South Eastman Southern Health Arbor Island (see Morton) Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Arborg Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arden Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Argue Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Argyle Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arizona Central Southern Health Amaud South Eastman Southern Health Ames Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Amot Burntwood Northern Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arona Central Southern Health Arrow River Assiniboine -

Keeyask Generation Project April 2014

REPORT ON PUBLIC HEARING Keeyask Generation Project April 2014 REPORT ON PUBLIC HEARING Keeyask Generation Project April 2014 ii iii iv Table of Contents Foreword . xi Executive Summary . xv Chapter One: Introduction. .1 1.1 Th e Manitoba Clean Environment Commission. .1 1.2 Th e Project . .1 1.3 Th e Proponent. .2 1.4 Terms of Reference . .3 1.5 Th e Hearings . .4 1.6 Th e Report. .4 Chapter Two: The Licensing Process . .7 2.1 Needed Licences and Approvals . .7 2.2 Review Process for an Environment Act Licence . .7 2.3 Federal Regulatory Review and Decision Making . .8 2.4 Section 35 of Canada’s Constitution. .8 2.5 Need For and Alternatives To. .9 2.6 Role of the Clean Environment Commission . .9 2.7 Th e Licensing Decision. .9 Chapter Three: The Public Hearing Process. 11 3.1 Clean Environment Commission . 11 3.2 Public Participation . 11 3.2.1 Participants . 11 3.2.2 Participant Assistance Program . 11 3.2.3 Presenters. 12 3.3 Th e Pre-Hearing . 12 3.4 Th e Hearings . 12 v Chapter Four: Manitoba’s Electrical Generation and Transmission System . 13 4.1 System Overview. 13 4.2 Generating Stations . 15 4.3 Lake Winnipeg Regulation and the Churchill River Diversion. 17 Chapter Five: The Keeyask Generation Project. 21 5.1 Overview. 21 5.2 Major Project Components and Infrastructure. 23 5.2.1 Powerhouse . 23 5.2.2 Spillway . 24 5.2.3 Dams . 24 5.2.4 Dykes . 24 5.2.5 Ice Boom . -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Section M: Community Support

Section M: Community Support Page 251 of 653 Community Support Health Canada’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services has developed the Children’s Services Reference Chart for general information on what types of health services are available in the First Nations’ communities. Colour coding was used to indicate where similar services might be accessible from the various community programs. A legend that explains each of the colours /categories can be found in the centre of chart. By using the chart’s colour coding system, resource teachers may be able to contact the communities’ agencies and begin to open new lines of communication in order to create opportunities for cost sharing for special needs services with the schools. However, it needs to be noted that not all First Nations’ communities offer the depth or variety of the services described due to many factors (i.e., budgets). Unfortunately, there are times when special needs services are required but cannot be accessed for reasons beyond the school and community. It is then that resource teachers should contact Manitoba’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services to ask for direction and assistance in resolving the issue. Manitoba’s Regional Advisor, Children’s Special Services, First Nations and Inuit Health Programs is Mary L. Brown. Phone: 204-‐983-‐1613 Fax: 204-‐983-‐0079 Email: [email protected] On page two is the Children’s Services Reference Chart and on the following page is information from the chart in a clearer and more readable format including -

Regional Stakeholders in Resource Development Or Protection of Human Health

REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS IN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT OR PROTECTION OF HUMAN HEALTH In this section: First Nations and First Nations Organizations ...................................................... 1 Tribal Council Environmental Health Officers (EHO’s) ......................................... 8 Government Agencies with Roles in Human Health .......................................... 10 Health Canada Environmental Health Officers – Manitoba Region .................... 14 Manitoba Government Departments and Branches .......................................... 16 Industrial Permits and Licensing ........................................................................ 16 Active Large Industrial and Commercial Companies by Sector........................... 23 Agricultural Organizations ................................................................................ 31 Workplace Safety .............................................................................................. 39 Governmental and Non-Governmental Environmental Organizations ............... 41 First Nations and First Nations Organizations 1 | P a g e REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS FIRST NATIONS AND FIRST NATIONS ORGANIZATIONS Berens River First Nation Box 343, Berens River, MB R0B 0A0 Phone: 204-382-2265 Birdtail Sioux First Nation Box 131, Beulah, MB R0H 0B0 Phone: 204-568-4545 Black River First Nation Box 220, O’Hanley, MB R0E 1K0 Phone: 204-367-8089 Bloodvein First Nation General Delivery, Bloodvein, MB R0C 0J0 Phone: 204-395-2161 Brochet (Barrens Land) First Nation General Delivery, -

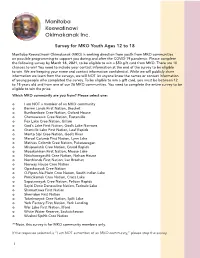

PDF File of the Survey from Here

Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak Inc. Survey for MKO Youth Ages 12 to 18 Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak (MKO) is seeking direction from youth from MKO communities on possible programming to support you during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Please complete the following survey by March 16, 2021, to be eligible to win a $50 gift card from MKO. There are 10 chances to win! You need to include your contact information at the end of the survey to be eligible to win. We are keeping your name and contact information confidential. While we will publicly share information we learn from the surveys, we will NOT let anyone know the names or contact information of young people who completed the survey. To be eligible to win a gift card, you must be between 12 to 18 years old and from one of our 26 MKO communities. You need to complete the entire survey to be eligible to win the prize. Which MKO community are you from? Please select one: o I am NOT a member of an MKO community o Barren Lands First Nation, Brochet o Bunibonibee Cree Nation, Oxford House o Chemawawin Cree Nation, Easterville o Fox Lake Cree Nation, Gillam o God’s Lake First Nation, God’s Lake Narrows o Granville Lake First Nation, Leaf Rapids o Manto Sipi Cree Nation, God’s River o Marcel Columb First Nation, Lynn Lake o Mathias Colomb Cree Nation, Pukatawagan o Misipawistik Cree Nation, Grand Rapids o Mosakahiken First Nation, Moose Lake o Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation, Nelson House o Northlands First Nation, Lac Brochet o Norway House Cree Nation o Opaskwayak Cree Nation o O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation, South Indian Lake o Pimicikamak Cree Nation, Cross Lake o Sapotaweyak Cree Nation, Pelican Rapids o Sayisi Dene Denesuline Nation, Tadoule Lake o Shamattawa First Nation o Sherridon First Nation o Tataskweyak Cree Nation, Split Lake o York Factory First Nation, York Landing o War Lake First Nation, Ilford o White Water Reserve, Saskatchewan o Wuskwi Sipihk Cree Nation **Note, this survey is for MKO community members only. -

Part1 Gendiff.Qxp

Sex Differences in Health Status, Health Care Use, and Quality of Care: A Population-Based Analysis for Manitoba’s Regional Health Authorities November 2005 Manitoba Centre for Health Policy Department of Community Health Sciences Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba Randy Fransoo, MSc Patricia Martens, PhD The Need to KnowTeam (funded through CIHR) Elaine Burland, MSc Heather Prior, MSc Charles Burchill, MSc Dan Chateau, PhD Randy Walld, BSc, BComm (Hons) This report is produced and published by the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP). It is also available in PDF format on our website at http://www.umanitoba.ca/centres/mchp/reports.htm Information concerning this report or any other report produced by MCHP can be obtained by contacting: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy Dept. of Community Health Sciences Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba 4th Floor, Room 408 727 McDermot Avenue Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3E 3P5 Email: [email protected] Order line: (204) 789 3805 Reception: (204) 789 3819 Fax: (204) 789 3910 How to cite this report: Fransoo R, Martens P, The Need To Know Team (funded through CIHR), Burland E, Prior H, Burchill C, Chateau D, Walld R. Sex Differences in Health Status, Health Care Use and Quality of Care: A Population-Based Analysis for Manitoba’s Regional Health Authorities. Winnipeg, Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, November 2005. Legal Deposit: Manitoba Legislative Library National Library of Canada ISBN 1-896489-20-6 ©Manitoba Health This report may be reproduced, in whole or in part, provided the source is cited. 1st Printing 10/27/2005 THE MANITOBA CENTRE FOR HEALTH POLICY The Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP) is located within the Department of Community Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba. -

Rcmp-Rrcmp-1942-Eng.Pdf

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. DOMINION OF CANADA REPORT OF THE ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE FOR THE YEAR ENDED MARCH 31, 1942 TO BE PURCHASED DIRECTLY FROM THE KING'S PRINTER DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC PRINTING AND STATIONERY, OTTAWA, ONTARIO, CANADA OTTAWA EDMOND CLOliTIER PR INTER TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY 1942 Price, 50 cents DOMINION OF CANADA REPORT OF' THE ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE FOR THE YEAR ENDED MARCH 31, 1942 - Copyright of this document does not belong to the Crown. -

Rcmp-Rrcmp-1965-Eng.Pdf

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. CANADA Report of the ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 1965 CANADA Report of the ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 1965 99876-1 , ROGER DUHAMEL, F.Ft.S.C. Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery Ottawa, 1967 Cat. -

Manitoba Justice Annual Report 2019

Manitoba Justice Annual Report 2019 - 2020 This publication is available in alternate formats, upon request, by contacting: Manitoba Justice Administration and Finance Room 1110-405 Broadway Winnipeg, MB R3C 3L6 Phone: 204-945-4378 Fax: 204-945-6692 Email: [email protected] Electronic format: https://www.gov.mb.ca/justice/publications/annualreports/index.html La présente publication est accessible à l'adresse suivante : http://www.gov.mb.ca/justice/publications/annualreports/index.fr.html Veuillez noter que la version intégrale du rapport n'existe qu'en anglais. Nous vous invitons toutefois à consulter la lettre d'accompagnement en français qui figure en début du document. ATTORNEY GENERAL MINISTER OF JUSTICE Room 104 Legislacivc Building Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 0V8 CANADA Her Honour the Honourable Janice C. Filmon, C.M., O.M. Lieutenant Governor of Manitoba Room 234 Legislative Building Winnipeg MB R3C OV8 May it Please Your Honour: I have the privilege of presenting, for the information of Your Honour, the Annual Report of Manitoba Justice, for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2020. Respectfully submitted, &f(� Honourable Cliff Cullen Minister of Justice Attorney General have included the expanded use of technology and improvement of existing technological infrastructure across the department, and expanded remote service delivery and work arrangements. As the pandemic continues, additional challenges and responses will emerge. I am confident that the Department will meet those challenges and develop, with our justice system partners, innovative and effective responses. I conclude by again acknowledging the tremendous efforts of our staff and of our justice system partners. Their exceptional innovation, dedication and collaboration assure me that together we will overcome the challenges we will face.