Pinus Aristata & P. Flexilis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tom Sharp's Post

19 Tom Sharp's Post Tom Sharp's Post, a log and adobe Indian trading station, built in 1870, is a familiar sight to those traveling Highway 305, in Huerfano County, between the remnants of Malachite and the top of Pass Creek Pass. The post, flbout a mile from the site of the once-thriving town called Malachite, stands near the Huerfano River crossing of the Gardner-Red Wing. road. Sharp's place was known as Buzzard Roost Ranch be cause hundreds of buzzards roosted in the cottonwood trees along the stream there. A well-traveled Ute Indian trail over the Sangre de Cristo range ran through the ranch, thence to Badito, and on to the Greenhorn Mountains. Ute Chief Ouray and his wife, Chipeta, often visited Sharp while their tribes men camped nearby. W. T. (Tom) Sharp, a native of Missouri, served with the Confederate forces at the beginning of the Civil War. His general was Sterling Price. In 1861, Sharp was paroled from the service because of wounds, and was placed in a wagon bound for the Far West. Surviving the trip across country, he joined a half-breed Indian hunter named "Old Tex,'' and for a time the two sup plied meat to mining camps in California and Oregon . Later Sharp headed eastward. With a partner, John Miller, he contracted to supply telegraph poles for the Union Pacific Railroad, then building into Wyoming. In 1867, he was a de puty sheriff in Cheyenne, Wyoming. In the autumn of 1868, Tom Sharp, John White, and John Williams, with an old prairie wagon, came into the Huerfano Valley looking for a location. -

36 CFR Ch. II (7–1–13 Edition) § 294.49

§ 294.49 36 CFR Ch. II (7–1–13 Edition) subpart shall prohibit a responsible of- Line Includes ficial from further restricting activi- Colorado roadless area name upper tier No. acres ties allowed within Colorado Roadless Areas. This subpart does not compel 22 North St. Vrain ............................................ X the amendment or revision of any land 23 Rawah Adjacent Areas ............................... X 24 Square Top Mountain ................................. X management plan. 25 Troublesome ............................................... X (d) The prohibitions and restrictions 26 Vasquez Adjacent Area .............................. X established in this subpart are not sub- 27 White Pine Mountain. ject to reconsideration, revision, or re- 28 Williams Fork.............................................. X scission in subsequent project decisions Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, Gunnison National Forest or land management plan amendments 29 Agate Creek. or revisions undertaken pursuant to 36 30 American Flag Mountain. CFR part 219. 31 Baldy. (e) Nothing in this subpart waives 32 Battlements. any applicable requirements regarding 33 Beaver ........................................................ X 34 Beckwiths. site specific environmental analysis, 35 Calamity Basin. public involvement, consultation with 36 Cannibal Plateau. Tribes and other agencies, or compli- 37 Canyon Creek-Antero. 38 Canyon Creek. ance with applicable laws. 39 Carson ........................................................ X (f) If any provision in this subpart -

Profiles of Colorado Roadless Areas

PROFILES OF COLORADO ROADLESS AREAS Prepared by the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region July 23, 2008 INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARAPAHO-ROOSEVELT NATIONAL FOREST ......................................................................................................10 Bard Creek (23,000 acres) .......................................................................................................................................10 Byers Peak (10,200 acres)........................................................................................................................................12 Cache la Poudre Adjacent Area (3,200 acres)..........................................................................................................13 Cherokee Park (7,600 acres) ....................................................................................................................................14 Comanche Peak Adjacent Areas A - H (45,200 acres).............................................................................................15 Copper Mountain (13,500 acres) .............................................................................................................................19 Crosier Mountain (7,200 acres) ...............................................................................................................................20 Gold Run (6,600 acres) ............................................................................................................................................21 -

Sangre De Cristo Salida and San Carlos Wet Mountains San Carlos Spanish Peaks San Carlos

Wild Connections Conservation Plan for the Pike & San Isabel National Forests Chapter 5 – Complexes: Area-Specific Management Recommendations This section contains our detailed, area-specific proposal utilizing the theme based approach to land management. As an organizational tool, this proposal divides the Pike-San Isabel National Forest into eleven separate Complexes, based on geo-physical characteristics of the land such as mountain ranges, parklands, or canyon systems. Each complex narrative provides details and justifications for our management recommendations for specific areas. In order to emphasize the larger landscape and connectivity of these lands with the ecoregion, commentary on relationships to adjacent non-Forest lands are also included. Evaluations of ecological value across public and private lands are used throughout this chapter. The Colorado Natural Heritage Programs rates the biodiversity of Potential Conservation Areas (PCAs) as General Biodiversity, Moderate, High, Very High, and Outranking Significance. The Nature Conservancy assesses the conservation value of its Conservation Blueprint areas as Low, Moderately Low, Moderate, Moderately High and High. The Southern Rockies Ecosystem Project's Wildlands Network Vision recommends land use designations of Core Wilderness, Core Agency, Low and Moderate Compatible Use, and Wildlife Linkages. Detailed explanations are available from the respective organizations. Complexes – Summary List by Watershed Table 5.1: Summary of WCCP Complexes Watershed Complex Ranger District -

THE GUNNISON RIVER BASIN a HANDBOOK for INHABITANTS from the Gunnison Basin Roundtable 2013-14

THE GUNNISON RIVER BASIN A HANDBOOK FOR INHABITANTS from the Gunnison Basin Roundtable 2013-14 hen someone says ‘water problems,’ do you tend to say, ‘Oh, that’s too complicated; I’ll leave that to the experts’? Members of the Gunnison Basin WRoundtable - citizens like you - say you can no longer afford that excuse. Colorado is launching into a multi-generational water planning process; this is a challenge with many technical aspects, but the heart of it is a ‘problem in democracy’: given the primacy of water to all life, will we help shape our own future? Those of us who love our Gunnison River Basin - the river that runs through us all - need to give this our attention. Please read on.... Photo by Luke Reschke 1 -- George Sibley, Handbook Editor People are going to continue to move to Colorado - demographers project between 3 and 5 million new people by 2050, a 60 to 100 percent increase over today’s population. They will all need water, in a state whose water resources are already stressed. So the governor this year has asked for a State Water Plan. Virtually all of the new people will move into existing urban and suburban Projected Growth areas and adjacent new developments - by River Basins and four-fifths of them are expected to <DPSDYampa-White %DVLQ Basin move to the “Front Range” metropolis Southwest Basin now stretching almost unbroken from 6RXWKZHVW %DVLQ South Platte Basin Fort Collins through the Denver region 6RXWK 3ODWWH %DVLQ Rio Grande Basin to Pueblo, along the base of the moun- 5LR *UDQGH %DVLQ tains. -

The Francis Whittemore Cragin Collection

The Francis Whittemore Cragin Collection Extent: Approximately 10 cubic feet. Finding Aid Prepared By: Michelle Gay, Spring 2001. Provenance: The materials in this collection were bequeathed to the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum in the will of Francis W. Cragin, and were received shortly after his death. If more information is needed, please see the archivist. Arrangement: Materials were divided into series according to original order and type. In all cases, priority was given to the preservation of original order. Copyright: The materials in the collection may be assumed to be copyrighted by the creator of those materials. The museum advises patrons that it is their responsibility to procure from the owner of copyright permission to reproduce, publish, or exhibit these materials. The owner of copyright is presumed to be the creator, his or her heirs, legates, or assignees. Patrons must obtain written permission from the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum to reproduce, publish, or exhibit these materials. In all cases, the patron agrees to hold the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum harmless and indemnify the museum for any and all claims arising from the use of the reproductions. Restrictions: The Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum reserves the right to examine proofs and captions for accuracy and sensitivity prior to publication with the right to revise, if necessary. The Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum reserves the right to refuse reproduction of its holdings and to impose such conditions as it may deem advisable in its sole and absolute discretion in the best interests of the museum. Oversized and/or fragile items will be reproduced solely at the discretion of the Archivist. -

Cochetopa Hills Vegetation Management Project Environmental Assessment

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service March 2014 Cochetopa Hills Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre and Gunnison National Vegetation Management Forests Gunnison Ranger District Project Environmental Assessment Saguache County, Colorado Lead Agency: USDA Forest Service Responsible Official: John Murphy, District Ranger, Gunnison Ranger District, GMUG NF Contact: Arthur Haines, District Silviculturist Gunnison Ranger District, GMUG NF Phone: 970 642-4423 Email: [email protected] The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14 th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Cochetopa Hills Vegetation Management Project Environmental Assessment Table of Contents 1. PROPOSED ACTION/PURPOSE OF AND NEED FOR ACTION........................................................1 1.1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. -

Southern Rockies Lynx Linkage Areas

Southern Rockies Lynx Amendment Appendix D - Southern Rockies Lynx Linkage Areas The goal of linkage areas is to ensure population viability through population connectivity. Linkage areas are areas of movement opportunities. They exist on the landscape and can be maintained or lost by management activities or developments. They are not “corridors” which imply only travel routes, they are broad areas of habitat where animals can find food, shelter and security. The LCAS defines Linkage areas as: “Habitat that provides landscape connectivity between blocks of habitat. Linkage areas occur both within and between geographic areas, where blocks of lynx habitat are separated by intervening areas of non-habitat such as basins, valleys, agricultural lands, or where lynx habitat naturally narrows between blocks. Connectivity provided by linkage areas can be degraded or severed by human infrastructure such as high-use highways, subdivisions or other developments. (LCAS Revised definition, Oct. 2001). Alpine tundra, open valleys, shrubland communities and dry southern and western exposures naturally fragment lynx habitat within the subalpine and montane forests of the Southern Rocky Mountains. Because of the southerly latitude, spruce-fir, lodgepole pine, and mixed aspen-conifer forests constituting lynx habitat are typically found in elevational bands along the flanks of mountain ranges, or on the summits of broad, high plateaus. In those circumstances where large landforms are more isolated, they still typically occur within 40 km (24 miles) of other suitable habitat (Ruggerio et al. 2000). This distribution maintains the potential for lynx movement from one patch to another through non-forest environments. Because of the fragmented nature of the landscape, there are inherently important natural topographic features and vegetation communities that link these fragmented forested landscapes of primary habitat together, providing for dispersal movements and interchange among individuals and subpopulations of lynx occupying these forested landscapes. -

Cochetopa Hills

COCHETOPA HILLS United States Department of Agriculture Forest VEGETATION MANAGEMENT Service PROJECT Gunnison, Grand PROPOSED ACTION Mesa and Uncompahgre National Forests Gunnison Ranger District Saguache County Colorado July 2013 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. 1 Cochetopa Hills Project Proposed Action 1. PROPOSED ACTION/PURPOSE OF AND NEED FOR ACTION 1.1. Introduction The U.S. Forest Service is planning vegetation management activities in the Cochetopa Hills area of the Gunnison Ranger District of the Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre and Gunnison National Forests. The Gunnison Ranger District is preparing this Environmental Assessment (EA) in compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and other relevant Federal and State laws and regulations. This EA will disclose the direct, indirect, and cumulative environmental impacts that are expected to result from the proposed action and alternatives to the proposed action. The Responsible Official will decide which actions, if any, to implement. Once a decision has been reached, a Legal Notice of Decision will be published in the Gunnison Country Times newspaper and the EA document will be made available for review. -

Mineral Resource Potential of National Forest RARE II and Wilderness Areas in Colorado

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Mineral resource potential of National Forest RARE II and wilderness areas in Colorado Compiled By Robert P. Dickerson 1 Open-File Report 86-0364 1986 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. Denver, Colorado CONTENTS (See also indices listings, p. 173) Page Introduction..................................................... 1 Grand Mesa, Gunnison, and Uncompahgre National Forests........... 2 Elk Mountains-Collegiate (2-180)............................ 2 Collegiate Peaks Wilderness (NF-180)........................ 2 Elk Mountains-Collegiate (2-180)............................ 5 Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness (NF-047)................... 5 Oh-Be-Joyful (2-181)........................................ 6 Ragged Mountain Wilderness (NF-181)......................... 7 Raggeds (2-181)............................................. 7 Drift Creek (2-182).......................................... 9 Perham Creek (2-183)........................................ 9 Springhouse Park (2-184).................................... 10 Electric Mountain (2-185)................................... 10 Clear Creek (2-186)......................................... 11 Hightower (2-189)........................................... 12 Priest Mountain (2-191)..................................... 12 Salt Creek (2-192).......................................... 12 Battlement Mesa (2-193).................................... -

2015 Report on the Health of Colorado's Forests

2015 Report on the Health of Colorado’s Forests 15 YEARS OF CHANGE Director’s Message January 2016 ponderosa pine and urban and community “we are all accountable for promoting the forests. In this year’s report, you will read about responsible stewardship of this valuable not only the current condition of our forests, natural resource.” That remains true today, but reflections on changes since the first report and although Colorado’s forest environments in 2001. are continually evolving, our commitment Much has been accomplished during the to their care and stewardship is constant. past 15 years. Perhaps most important, forestry- Thank you for building on your knowledge related legislation ratified by the Colorado and awareness of our forests, so that you too General Assembly has had positive impacts can advocate for their stewardship and the on the health and diversity of Colorado’s benefits they provide. forests. Many essential forestry-related bills have passed through the State Legislature, ▲ Michael B. Lester, State Forester enabling community-based forest restoration, and Director. Photo: Society of providing guidelines and criteria for counties to Michael B. Lester American Foresters prepare Community Wildfire Protection Plans, State Forester and Director and fostering intergovernmental cooperation. Colorado State Forest Service This year marks a milestone in tracking forest The Colorado Healthy Forests and Vibrant health and management in Colorado, with this Communities Act of 2009, which still provides publication representing the 15th annual report resources to the Colorado State Forest Service on the health of Colorado’s forests. Throughout to address wildfire risk, augment outreach this period, we’ve witnessed many landscape- efforts and provide forest treatment solutions, level changes across Colorado. -

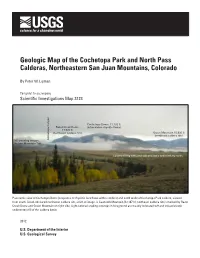

Geologic Map of the Cochetopa Park and North Pass Calderas, Northeastern San Juan Mountains, Colorado

Geologic Map of the Cochetopa Park and North Pass Calderas, Northeastern San Juan Mountains, Colorado By Peter W. Lipman Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3123 Cochetopa Dome, 11,132 ft Razor Creek Dome (intracaldera rhyolite flows) 11,520 ft (northwest caldera rim) Green Mountain,10,930 ft (northeast caldera rim) NE-trending tongue, Cochetopa Canyon Nelson Mountain Tuff Caldera-filling tuffs and volcaniclastic sedimentary rocks Panoramic view of Cochetopa Dome (sequence of rhyolitic lava flows within caldera) and north walls of Cochetopa Park caldera, viewed from south. Cloud-obscured northwest caldera rim, at left of image, is Sawtooth Mountain (12,147 ft); northeast caldera rim is marked by Razor Creek Dome and Green Mountain on right side. Light-colored eroding outcrops in foreground are weakly indurated tuff and volcaniclastic sedimentary fill of the caldera basin. 2012 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................1 Ignimbrite caldera cycles and eruptive processes .................................................................................1 Methods of study ...........................................................................................................................................2 Regional framework ......................................................................................................................................3